Central Park

Conservationist Elizabeth Barlow Rogers’ thoughts on the richness of Bruce Davidson’s photos of the famed New York City space, and the photographer’s own notes on the characters he met there

Working in New York City’s Central Park over four years, Bruce Davidson made images of the vibrant life and activities that take place in the well-loved green space. The Magnum photographer and New York resident captured youthful play, rendezvous-ing couples, and citydwellers at rest in the park. He also became acquainted with a variety of eccentric characters —his reflections of meeting these individuals, taken from his book Central Park, are republished below. His notes are prefaced by a text by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers on the richness of Davidson’s work made in the famed space. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers is a landscape designer, preservationist and writer, founder of the Central Park Conservancy, and President of the Foundation for Landscape Studies.

Bruce Davidson’s poster of Central Park’s Lake and Bow bridge, and fine prints of his other images from New York City are available to shop now as part of our New York: Photographing the City collection, which can be viewed here.

Created in the middle of the nineteenth century, Central Park is a product of humanitarian reform and picturesque romanticism. Then, it was felt by its designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, to be a civilising force, a healthful and spiritually refreshing counterpoint to the burgeoning Industrial Age metropolis that would soon surround it. In their then-novel democratic experiment, they believed that scenery, artfully arranged to resemble pastoral meadows and natural woodlands, would act as a moral agent operating beneficially on the sense of the rich and poor alike.

The Sheep Meadow, the Ramble, the Dene, and the Meer—the park’s bucolic spaces have names that fall quaintly on the modern ear. Although twenty-six ball fields have been inscribed upon Olmsted and Vaux’s rustic text in this century, the true glory of Central Park is the humanizing effect its tranquil meadows and secluded byways produce on those who frequent them. As Olmsted described it, “The character of this influence is a poetic one [whereby] the mind may be more or less lifted out of moods or habits into which it is, under the ordinary conditions of life in the city, likely to fall.”

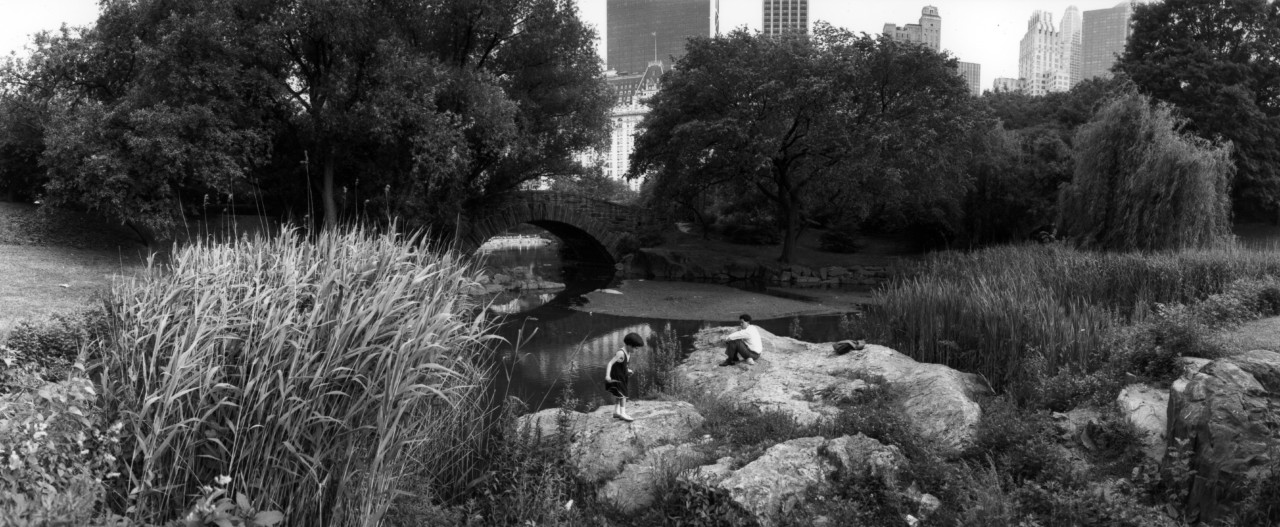

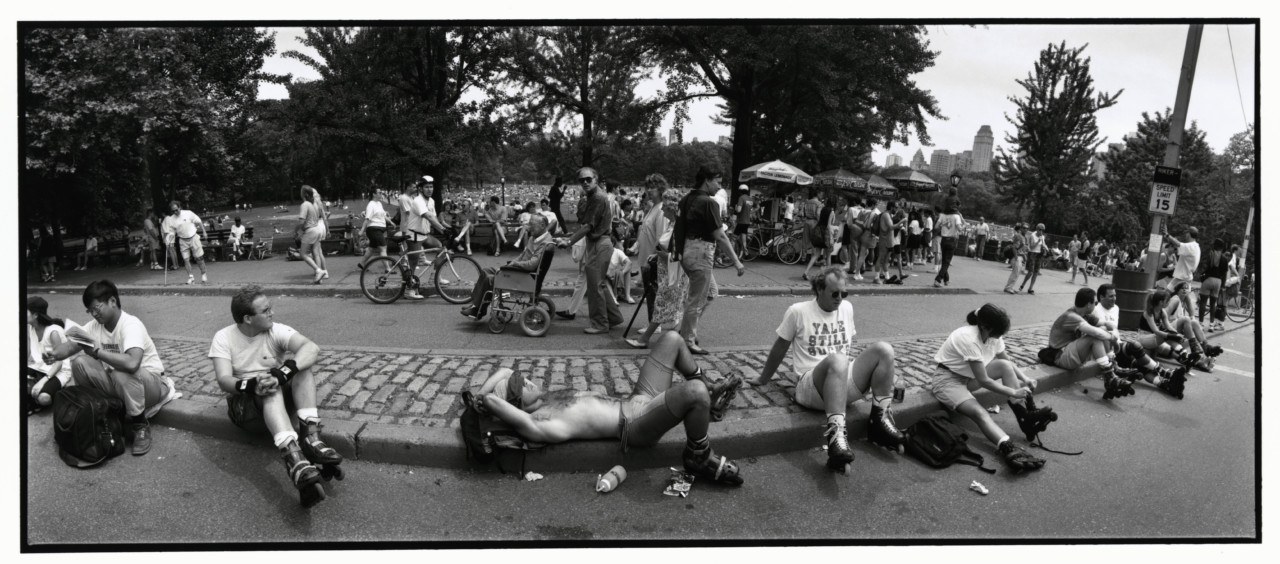

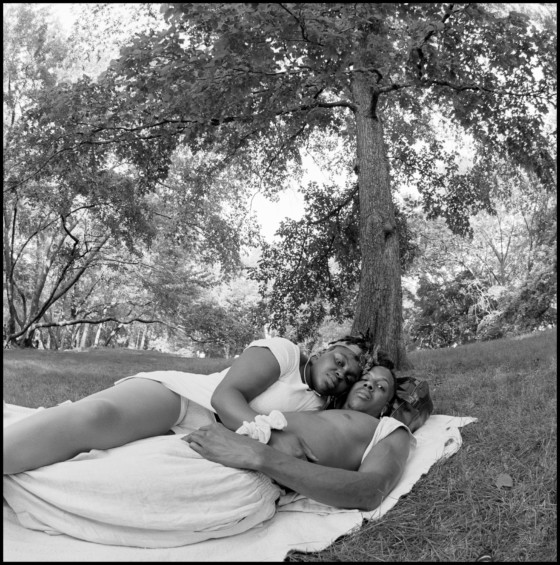

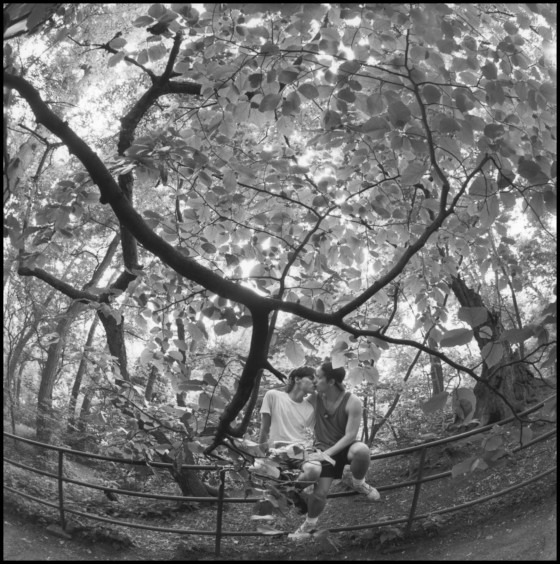

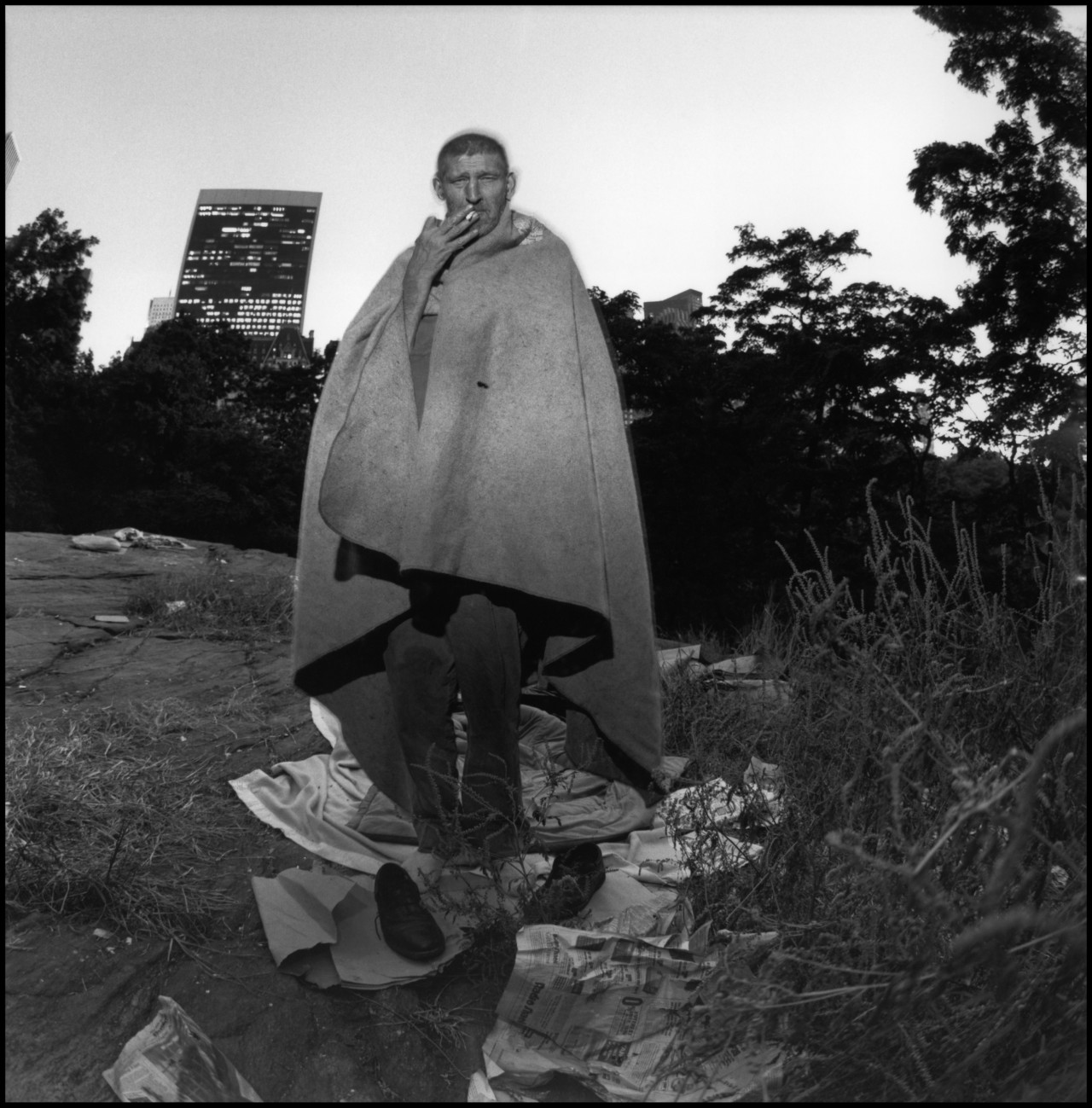

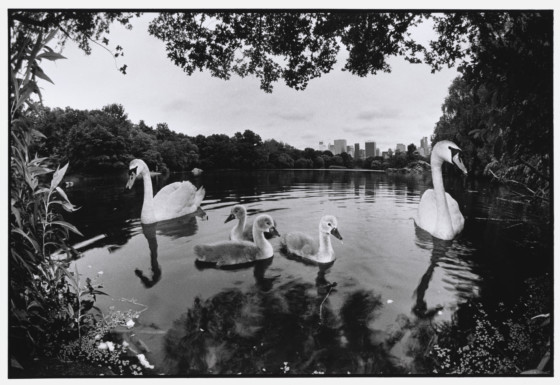

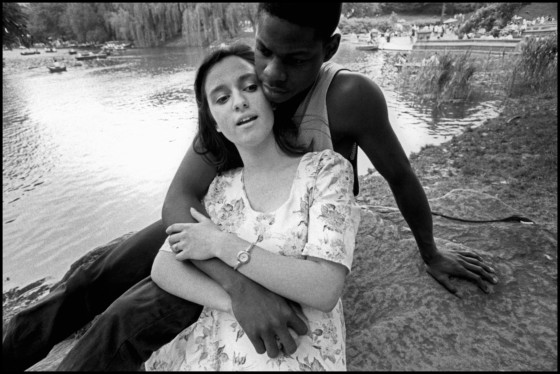

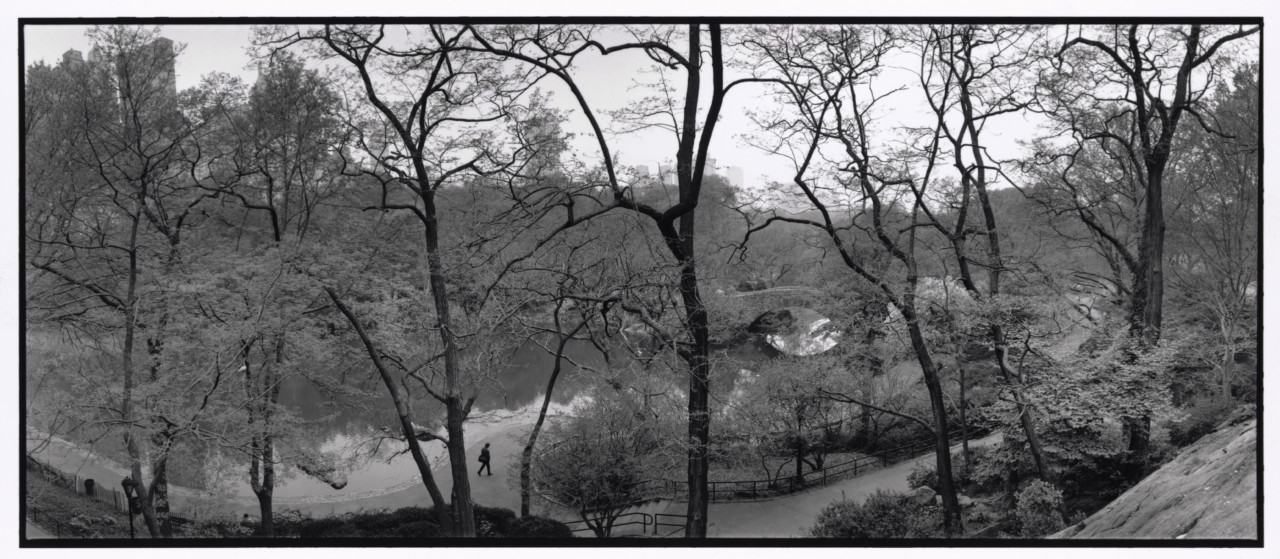

This is the Central Park that Bruce Davidson sees, a place of poetic encounter, a space in which epiphanies are everywhere to be found, if one is patient—and observant. His uncommon eye, and the cameras that are the instruments of his art, focus upon the secrets that the park reveals to one who visits it in all its hours and seasons and weathers. Through Davidson’s photographs we can observe how the park opens its hospitable, generous heart to the city, offering temporary refuge for those without shelter, privacy for the lover, a setting for the newlywed, nesting space and food for the newly hatched, a circle of sunlight for the wheelchair-bound, and all of outdoors for energetic youthfulness. In Davidson’s work we discover the park to be a great theatre of human, animal, and vegetal life, a place where nature and humanity interact and in the process become mutually transformed.

One sees the effects of place upon the human psyche in the faces and bodies of Davidson’s subjects. In their features and in their poses we discern the effects of the park’s magic, how it induces sometimes a meditative feeling, sometimes sensuality, sometimes exuberance. The works seems to say, “Here, in this space, we are more alive. Here our loneliness is made bearable. Here we are more truly ourselves.”

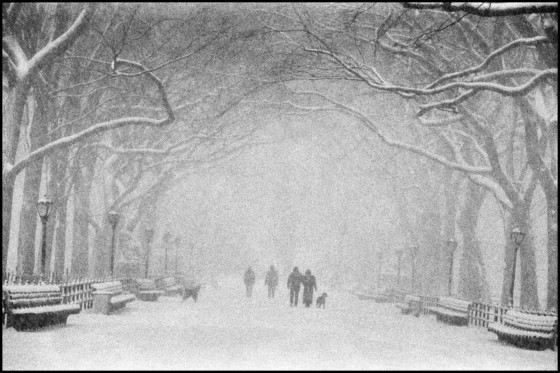

Observed in this way, the park itself quickens to new life and meaning. At no time is this more true than during and after a snowstorm, when those who venture there give it the aspect of a small rural village, tranquil yet infused with communal joy.

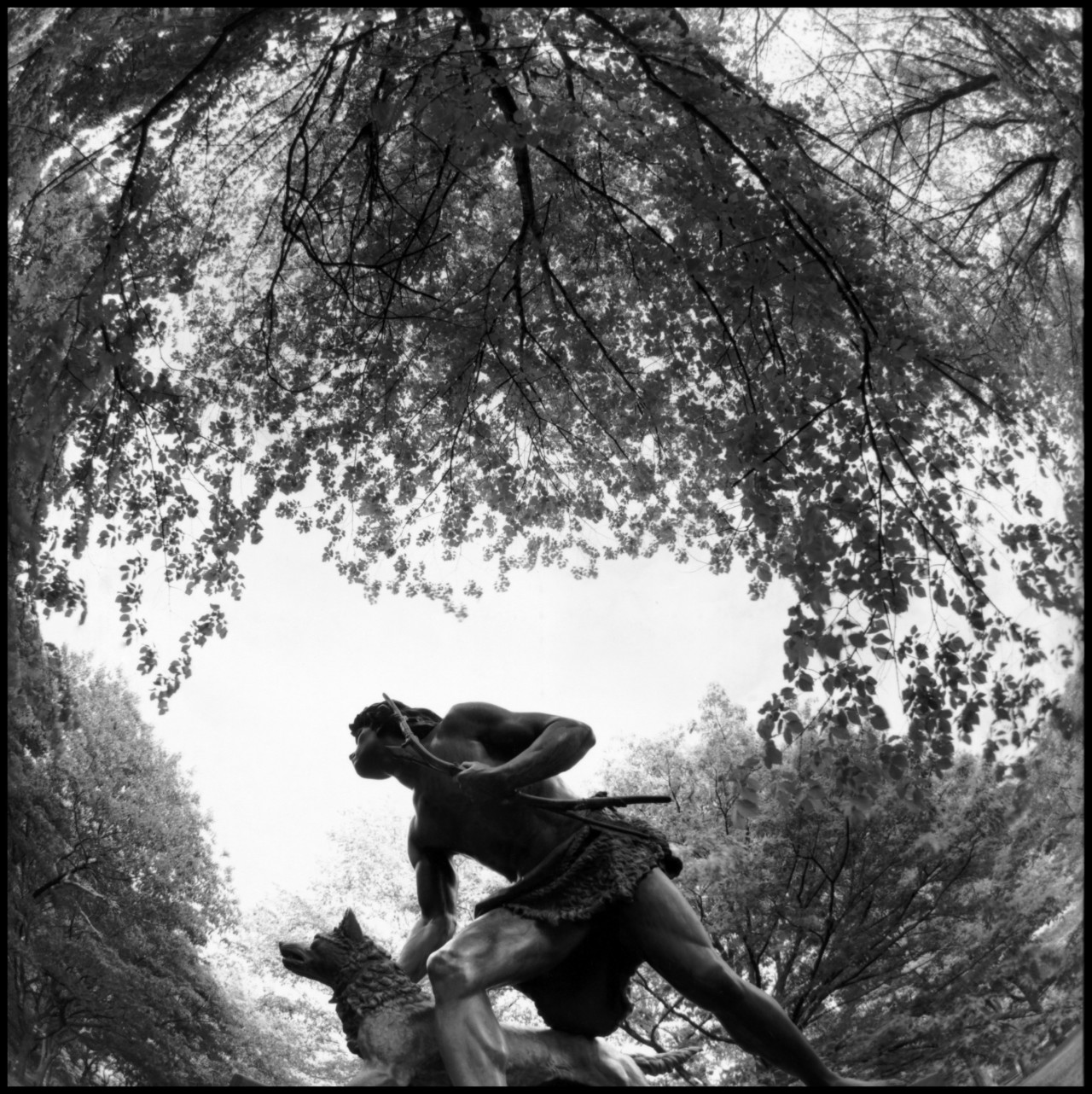

Even the statues become more alive in Davidson’s photographs. Lens and camera angle liberate them from their bases and propel them into action. They too begin to move through the park. See how The Eagles are ready to take flight! Do the joggers on the East Drive even suspect that Still Hunt, the bronze cat, is ready to pounce? No longer frozen beneath the elms of the mall, The Indian Hunter is stealing through the forests primeval, stalking his prey. And the bird-watchers on the page opposite The Falconer are right to train their binoculars on the raptor he holds aloft: it is about to soar.

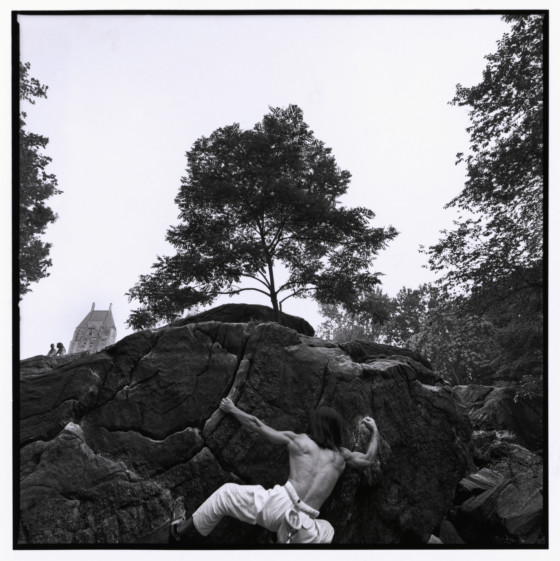

[In Davidson’s book, Central Park,] torsos and trees, rocks and faces, branches and human limbs interweave, forming resonant patterns. The cumulative impact of this visual fusion of par and people is moving, like music. Through Davidson’s photographs, the mysteries of Central Park become unforgettable.

The following is extracted from Bruce Davidson’s notes in the book Central Park.

Lola is an elegant woman with delicate done structure, opal skin, and alert eyes She tells me she was a designer of hats for Mr John in the forties, but now devotes herself to caring for the pigeons, ducks, cardinals, sparrows and other birds with an array of breads, seeds, nuts, and corn she carries in a shopping cart. I show her a small portfolio of my park pictures that I carry in my safari jacket pocket, and tell her that I am interested in photographing nature and people as an homage to the park. She asks me not to show her face in any of the pictures.

[…]

During the four years I have working the park, I have seen Lola feeding her birds early in the morning in driving rain, snowstorms, and on hot summer days. When a blizzard hit the city, I saw her wrapped in large trash bags billowed into a graceful garment while she fed the ducks along the frozen pond, pigeons pecked and flew around her, and gulls scavenged morsels on the ground, and she turned toward the bends to get more food. The storm was still brutally raging; I could see her face was frozen and her glasses covered with frost. I instinctively brought my camera to my eye and caught her facing me. Her glance back at me was sharp, like a bird seeing a predator. I had betrayed her trust: I no longer existed for Lola; she never looked at me again.

Bill has lived in the park for several years. In winter, he sleeps under Bethesda Terrace on a cardboard carton and covers himself with old army blankets. In summer, he stays on a grassy knoll overlooking the statue of the Angel of Water at the lake. Bill once worked in a factory in the rural South, but now he earns wages gathering paper and other debris along the park perimeter, in a program called “Trash for Cash.” He also collects cans that he takes to a redemption center, receiving five cents for each can. Other homeless men in the park call him “Bigfoot,” because he is a big man whose shoe size is too large for anyone else, so no one tries to steal his shoes. Bill knows the nature that surrounds him. He knows what time it is by watching lights in buildings across the park, and he once showed me a place where a mother duck was sitting on her nest near a gazebo at the lake, where he sometimes sleeps. I asked if I could photograph him in the morning as he gets up, and he agreed. I showed him my work, and gave him prints of himself that he put into the garbage bag that serves as his suitcase. One day, I asked him his birth date, and he said he was going to be fifty-one in a few days. It was a shock to me that he was younger than myself. On his birthday, I brought him a small metal thermos I had carried all over the world on various assignments. I wanted to give him something that I would miss not having. He told me that it could be stolen from the stash that he hides in the bushes while he is working, but he thanked me. One evening, I photographed him on Overlook Rock with the city skyscrapers in the background before he went to sleep. I asked I could come back the next night to photograph him again, but he said, “Not tomorrow, I am going to be in Yonkers. There is a Trash for Cash meeting. I’m on the board of directors, and can’t miss it.”

[…]

Central Park is a man-made environment that can make us believe we are in the wilds of Minnesota or on the peaks of the Bridger Wilderness. As we stroll the Ramble, explore the Ravine, or jog along the Reservoir, the line between reality and illusion is blurred. The park has trees more than a century old. Several hundred millions of years ago some of its rocks were under the sea. Now in summer, children swinging on limbs over a body of gleaming water at sunset give a sense of the continuum of nature. On an embankment along a lake, a large snapping turtle lays and then lowers its eggs, gently, one by one into a hole it has slowly dug out with its powerful back claws. It then carefully covers up the eggs with the soil it has removed, turns and disappears back into the murky water. Later on in the same area, a mother swan with three signets riding on its back glides close to the shore with the city skyline set in the background.

[…]

The ravine is one of the most beautiful wooded sections of the park, and one of the most secluded. One day I decided to climb its steep slopes to reach the Block House, which sits on top of the hill and offers a view of Harlem. This structure is a remnant of a stone fortress used as a lookout in the War of 1812 to spot ships coming up the East River. Now it is a shell, with a rusty iron door and no roof. Crack vials litter its grass-and-dirt floor. After hiking for a while, I eventually came to a large rock, and the charred remains of a small campsite. Two men were standing nearby, one short and the other very tall. I passed them, muttering a greeting, and as I went on, I had the uneasy feeling they might rob me. I looked back and saw them talking and looking at me. With some trepidation, I decided to continue to the Block House. As I climbed the steep steps, I came to a person leading a large dog on a heavy chain leash. What a great dog you have. What Kind is it?” I asked politely. The man replied proudly: “This is a bullterrier.” We proceeded together to the top of the hill, and on the the Block House. I asked if I could photograph his dog. He consented. I stood at a respectful distance; the dog eyed me suspiciously. Behind me, I noticed the two men from the campsite standing in the bushes, watching. I said to the man, “Those two guys back there are going to rob me when you leave.” He told me he had stopped two robberies with this dog in the past year. “They had the nerve to come up to me with my dog right there. I said to them, ‘This dog doesn’t growl, he doesn’t bark, he waits for my command, and then lunges for the throat.’ They left me alone.” I asked if I could accompany him as he left the park. The dog never took his bulging eyes off me. In a few days I sent the man some prints.

Maria cooks fried chicken, sausages, and plantains over a charcoal fire behind the backstop at the hardball fields at 102nd Street and the East Drive; the fire is also fuelled with broken hardball bats and scraps of wood. Semiprofessional teams play every weekend. One Sunday, the Bustelo Coffee Company team, wearing gray uniforms with red script letters, was playing the Morgan Stanley Investment Banking Company, suited up in white Yankee pinstripes. The scoreboard read 9 to 1, in the bottom of the fifth, in favour of the coffee company. I am told that big-league scouts often watch these games looking for potential players. In the past, I have given Maria several photographs of herself, and whenever I arrive she offers me a chicken dinner and cold soda.

[…]

It is a sunny March morning; the air is still cool but the sun is strong, and buds are beginning to appear on the trees. I have not been to the park for several weeks, and I set out to look for Bigfoot. I look for him at the Heckscher headquarters, where he gets his uniform and tools for work, but I’m told that nobody has seen him since December, that perhaps he has gone to a shelter. I then decide to visit Lola, who is feeding the ducks at the pond. I say good morning several times—from a respectful distance—but she mutters that she is not talking to me. I see that mending our relationship, shattered two years before, is hopeless, and walk away. Continuing to the zoo and then to the model-sailboat pond, I notice a redtail hawk circling overhead, When I eventually reach my final destination, Loeb Boat House, I find the “bird book,” in which bird-watchers from all over the world make entries, and write: “March 24, 1995, at about 8 A.M. on a path near Conservatory Water. Sighting of a redtail hawk with something protruding from his or her beak. It is either a twig, or a tail of a rodent. It circles high above me, and climbs—gliding toward its nest under a ledge of an apartment building on Fifth Avenue.

Signed, Bruce Davidson.”