Josef Koudelka: Gypsies

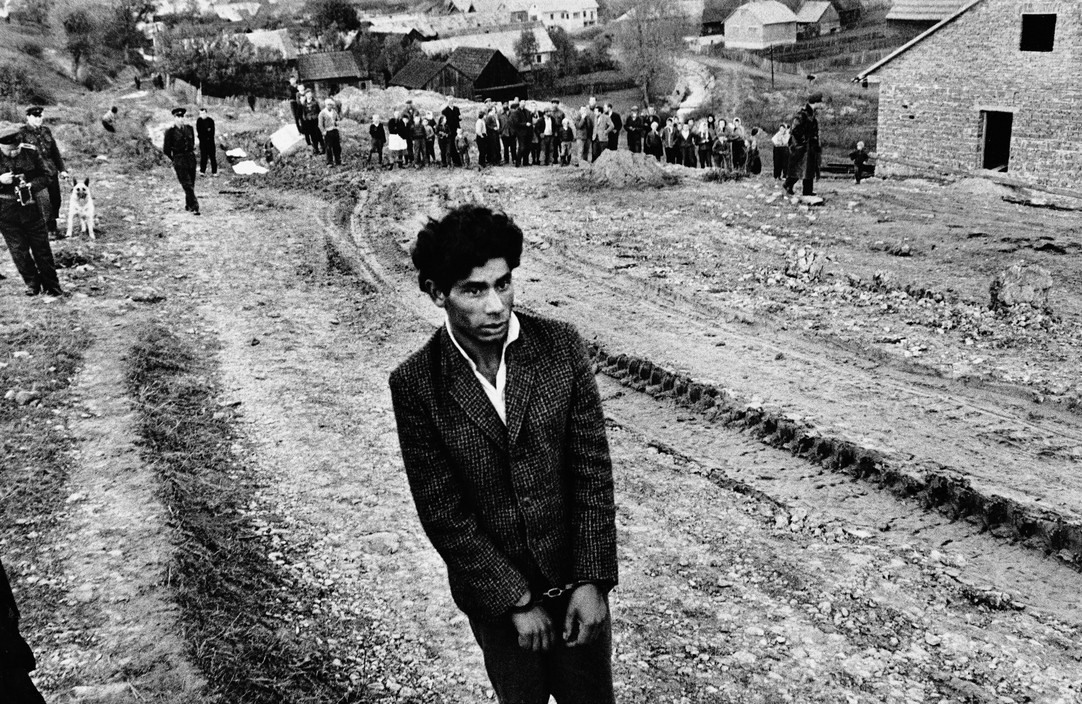

Koudelka’s photoessay captures the lives of Roma communities across Europe and marked the beginning of his own experience of exile

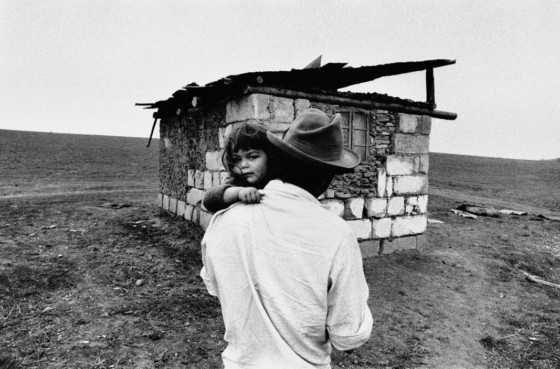

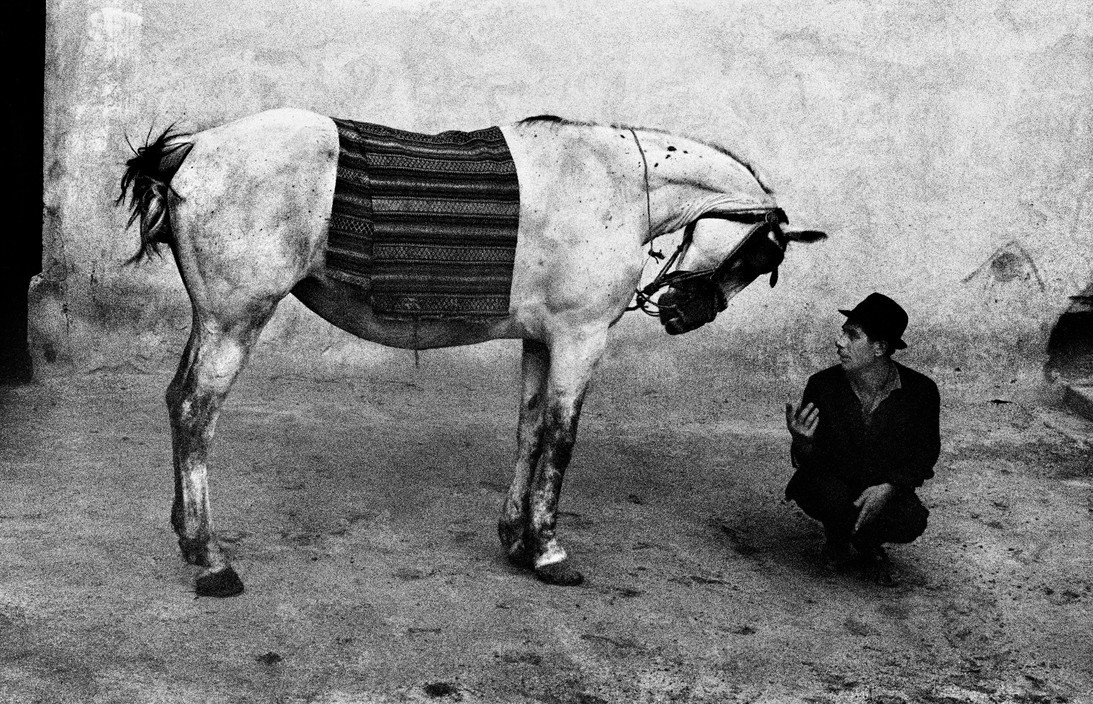

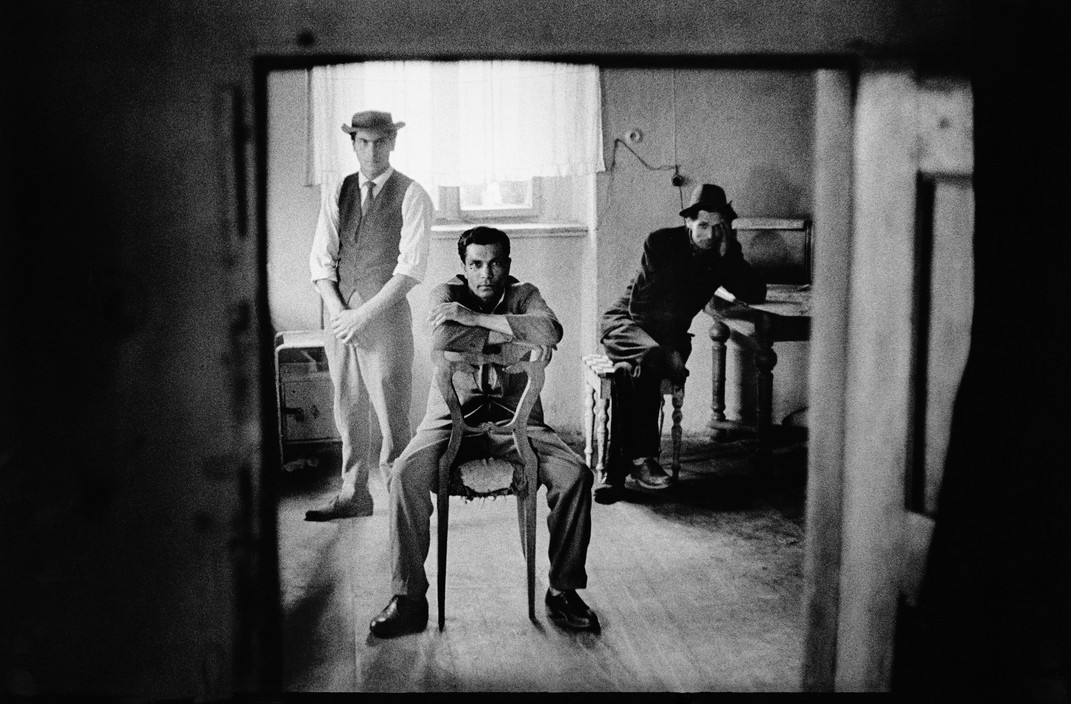

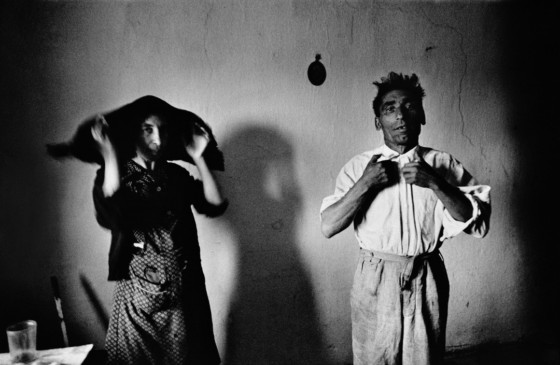

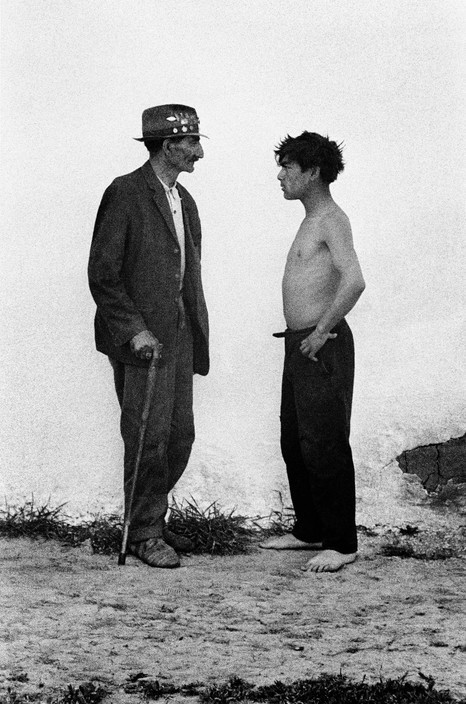

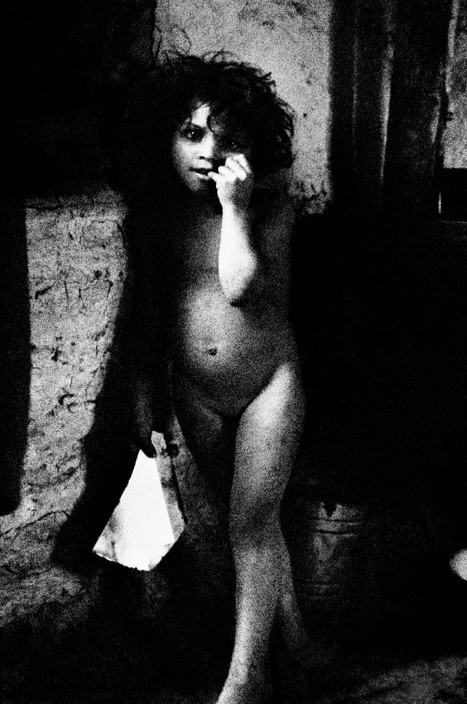

One of the seminal photoessays of the 20th Century, Magnum photographer Josef Koudelka’s Gypsies offers an unparalleled insight into the everyday lives of Europe’s Roma communities. Carrying only his equipment, a rucksack and sleeping bag, Koudelka moved freely between different villages and encampments during the Sixties and early Seventies, sleeping outside and spending his days immersed in recording the individuals he encountered. Akin to the communities he was photographing, Koudelka’s life during this period was characterized by displacement and alienation. It was undoubtedly his affinity with these people’s way of life that both drove him to photograph them and enabled Koudelka to capture the intimacies and intricacies of their existence to such an unprecedented degree.

After taking what became his career-making photographs of the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Koudelka feared for his safety and made plans to leave his homeland. Capturing the confrontation between Russian tanks and unarmed protesters in the streets of Prague, his images were smuggled out of the country and published under a pseudonym in The Sunday Times Magazine. Despite this precaution, in 1970 Koudelka fled to England to apply for political asylum and became, like many Roma in his images, effectively stateless. Indeed, both Gypsies, and his subsequent project Exiles, center around the theme of displacement, which was a defining reality of his own existence.

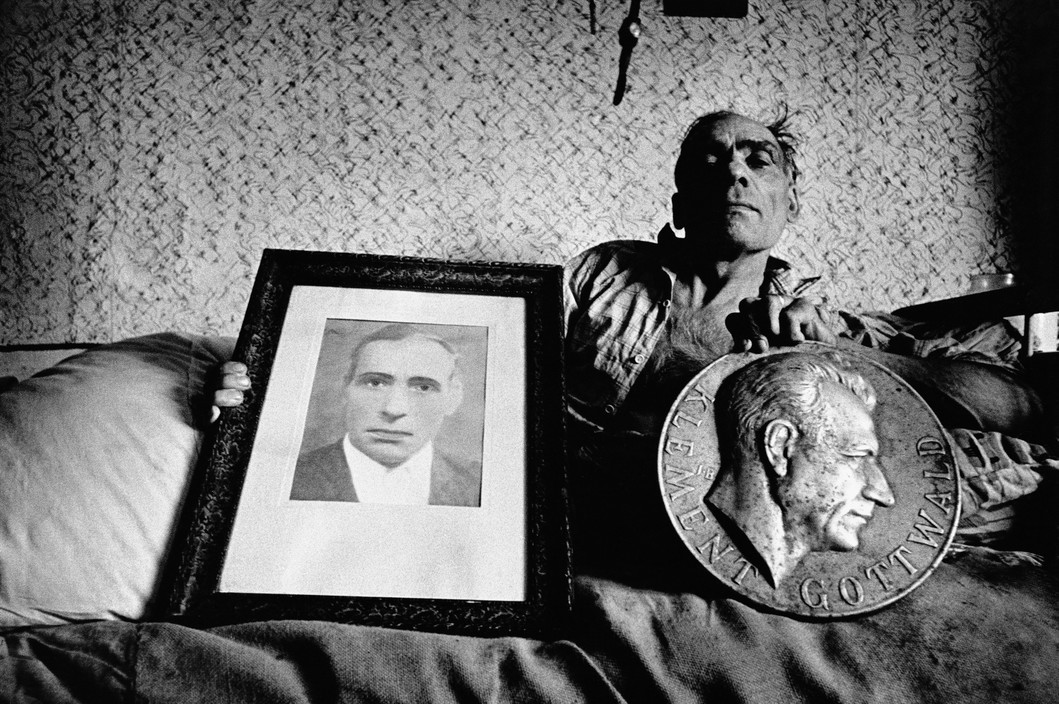

Taken over the course of a decade, from 1962 to 1971, the series of candid black and white images capture the daily lives of Roma society in the then-Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, France, and Spain at a time of uncertainty for the community. The advent of a Communist government in post-war Czechoslovakia, with its promises of equality, seemed to offer hope after the horrors experienced by Roma across Europe, at the hands of the Nazis during World War II. However, by the time Koudelka started his project, an ambitious drive to end their nomadic lifestyle and fully assimilate all Roma people into society had already begun. Although many Roma were not averse to entering the mainstream labor force and taking up offers of housing, persistent efforts to undermine and eradicate their identity, although mostly failed, were deeply humiliating.

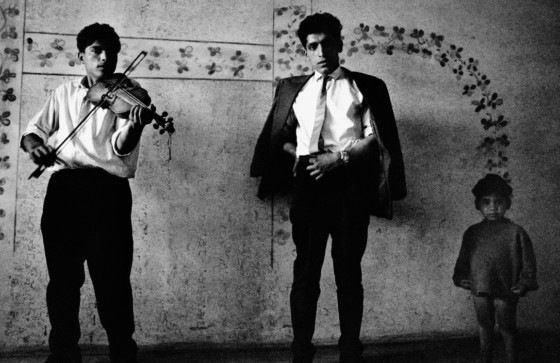

Gypsies exists as an invaluable documentation of a people during a tumultuous time in their history. From an image of a trio of suited musicians engrossed in their instruments, to stirring portraits of families in cramped living conditions, the photoessay is both a testament to the strength of Roma culture and a stark document of the realities of these people’s lives. Having fully immersed himself in the project, Koudelka’s work presents an unbiased and honest portrait of a community whose nomadic way of life has been contested throughout history.

For many Roma in Europe, the decade in which Gypsies was photographed is now remembered as a Golden Age in their past. The Communist regime in Czechoslovakia facilitated both improvements in their quality of life and safeguarded against the racism they had been victims of both before and during World War II. With the disintegration of this government in 1989, and a return to democracy, the quality of life for the Roma rapidly deteriorated and, despite efforts across Europe, for many, their situation remains dire today.