The Dark World of Pokémon Go!

Thomas Dworzak takes a broad approach to documentary photography in his latest exploration into human behavior

There is a scene in the 1961 French-Italian film L’Année dernière à Marienbad where characters, rendered in black and white, move enigmatically around the grounds of a palatial château. There is something curious and slightly off about their difficult interactions, their jagged positioning combined with the geometrically manicured gardens evoke a game of chess. This plays into the experimental narrative structure of the film, in which time and space are warped concepts. This summer, Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak observed a similarly curious phenomenon in Paris. On returning to the city this summer after some time traveling, he was intrigued by slow-moving crowds of people, hunched into their iPhones, walking with a sense of purpose and then stopping suddenly on seemingly invisible marks. They had discovered the augmented reality videogame app sensation Pokémon Go!.

“I was back in Paris and walking round and suddenly there was this very weird movement. I was in the park with my wife and people were coming from all sides looking down at their phones – it was very beautiful, the whole scenario. The movement of groups of people was very interesting. It’s very graphic and very strange. They’re like figurines in a play.”

A Document of Behaviour

A documentary photographer whose interests lie in human behavior and society, Dworzak’s way of understanding the phenomenon was to photograph it. His panning black and white shots of the people of Paris echo the mysterious movements of Alain Resnais’s cinematic masterpiece. “I spend a lot of time in my life travelling to exotic places and exotic countries and dealing with that kind of stuff, so I sort of looked at this in a similar way. This is something totally strange, something different. This is the Western world and culture.”

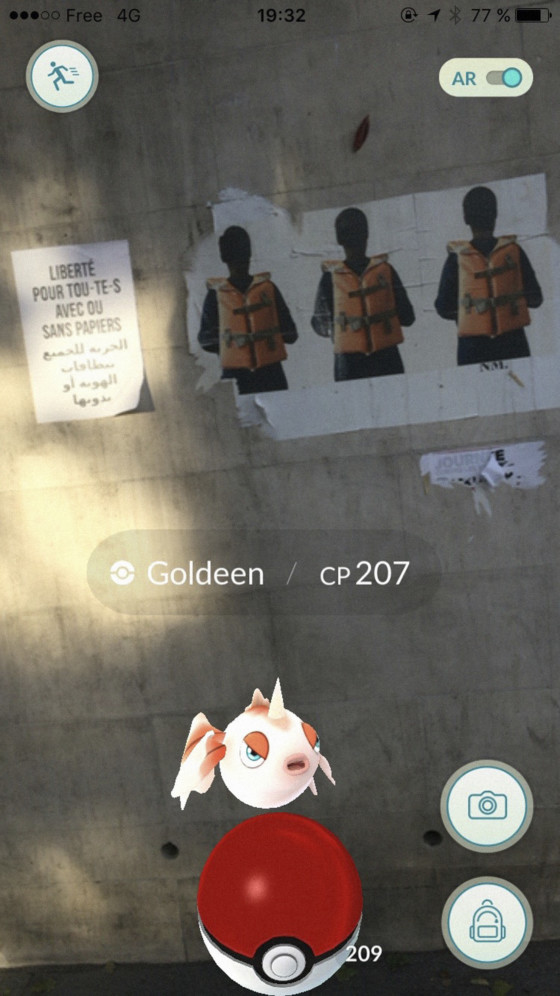

In order to deepen his understanding, Dworzak decided to download Pokémon Go! himself. He allowed the game to be his guide, gravitating towards spots the it led him to, and passively opening up the app just to see what was there. “I chose these spots because the game gave them to me. The first PokéStop that I found was a memorial plate for twenty three French school children who had been brought to Auschwitz, which I thought was dark.” Taking both iPhone screen grabs and using the in-app camera, which is part of the game, Dworzak began to build up a study of the augmented reality game’s relationship with the physical world, and human beings’s changing relationship to their surroundings.

"I don’t really know what to make of it. I want to leave it open because I want to know what people will think about it"

-

Dark Tourism

Dworzak, who has an interest in the phenomenon of dark tourism, discovered the cartoon ‘catch-em-all’ game took him to some unexpectedly sensitive places: “I went to a concentration camp and memorial and there is actually a sign on the entrance that says ‘Don’t play Pokémon’, which I understand. I went to the locations and I was like, ‘Okay, look, if there is none then there is none,’ and I just left it on. But, strangely enough a couple of them appeared whilst I was walking around. There were two Pokémon, not exactly inside the thing, but using the memorial, the monument commemorating the deportation of people in World War II.”

“I don’t really know what to make of it. I want to leave it open because I want to know what people will think about it. There are people screaming out about how horrible it all is, but then there’s people who tell me it’s nice because their kids are interacting with history. I feel weird, I mean, I took the picture because I’m there, but I thought it was strange. There’s a war cemetery in Normandy where the entire cemetery is separated by PokéStops. The Bataclan in Paris, the place where the terror attack was in November 2015 is a PokéGym. It’s pretty strange; for me, these are places associated with something very sad.”

“I went to photograph Rouen when the priest there was killed by terrorists, for my normal work, and I’m standing at the police cordon and there’s these kids on bicycles and they’re like, ‘Yeah, yeah, I got one,’ ‘Oh, there’s another one over there,’ ‘Oh f**k we can’t cross the police line.’ It turned out the Church where this happened was a PokéStop, but that I think may because in a small village that’s a landmark.”