Man and Land

Stuart Franklin on creating visual odes to the world’s landscapes

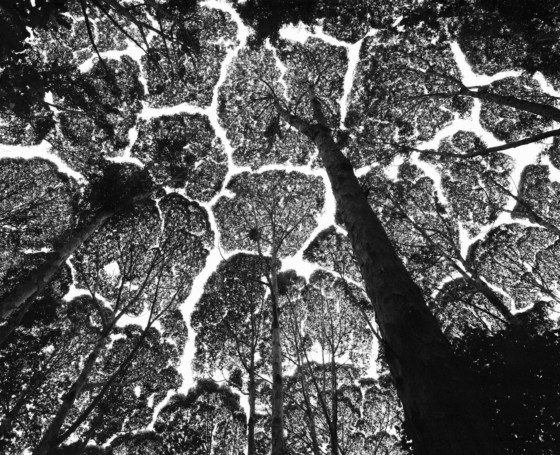

Stuart Franklin’s thorough exploration of the natural world may have an academic grounding but his approach to photographing it is more poetic than clinical. According to Franklin, nature photography “engages with the idea of a shared landscape that is in some lovely, special, beautiful, way enjoyed by people for its own sake.” Just as great poets of nature mused on trees in their writing – “Their greenness is a kind of grief” observed Philip Larkin – Stuart Franklin believes that photography also “can allow us to dwell and reflect”.

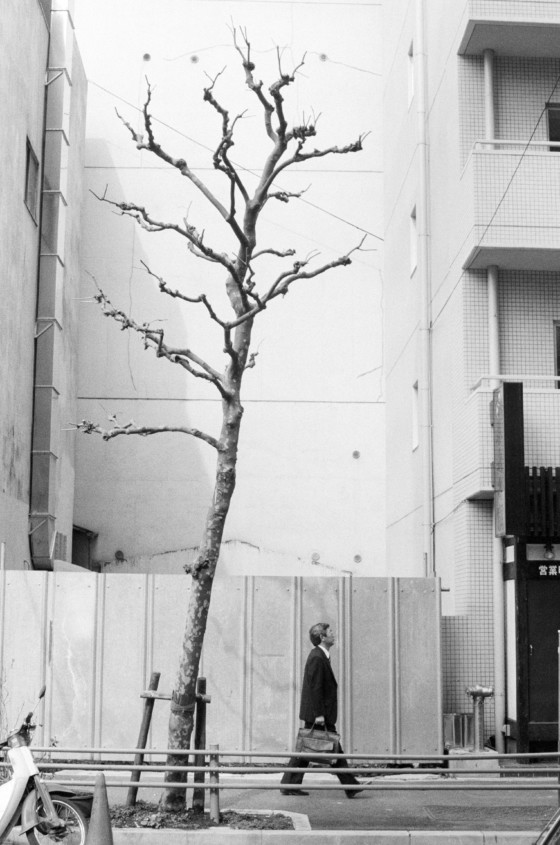

Having witnessed environmental change through both his academic and photographic studies, Franklin is philosophical about the relationship between man and the land, accepting that it is a double-edged sword; and it’s reductive to discuss it purely in terms of “humans being a blot on the landscape wherever they appear.”

“Many rivers and drainage basins are cleaner now than at any time in the past one hundred and fifty years. Forests are regenerating, notably in Scotland and Poland. Cities are considerably cleaner,” he wrote in the foreword to Footprint: Our Landscape in Flux (2008).

"I’m interested in the whole nature-society phenomenon; the way in which we anthropomorphize aspects of the landscape and see ourselves reflected in it or as shadows across it"

- Stuart Franklin

A poetic take on the classic trope

The age-old idea of nature photography capturing the intersection between man and the land, and often employed as a lobbying tool, has been around almost as long as the practice of photography itself; the work of mid-19th century photographer William Henry Jackson was instrumental in convincing US Congress to create the Yellowstone National Park; and as global warming and pollution issues entered political consciousness, photographers have tapped their trade to report on the way the earth has been damaged by humans. Magnum nominee Michael Christopher Brown recently visited the Marshall Islands to photograph the geographical and human impact of rising sea levels, for example.

Stuart Franklin’s study of the relationship between man and nature is more introspective, exploring something of man’s psyche. Through his work, Franklin draws out the parallels between the way mankind sees the land and how it sees itself, projecting his personal theories on this through his visual meditations on nature. The loaded title of his photo essay Narcissus makes this link explicit. “I’m interested in the whole nature-society phenomenon; the way in which we anthropomorphize aspects of the landscape and see ourselves reflected in it or as shadows across it,” he says.

Of Forests and Flux

The “notion of environmental impact” inspired Franklin’s book Footprint: Our Landscape in Flux, in which he explores glacial retreat in Austria, Pittsburg and Norway. “I looked at how lives and cities were changing because of hotter summers with outdoor pools, riversides turning into swimming pools, like in Berlin, for example.” His work is almost scientific in his observational distance, looking at the ebbs and flows of environmental development and change without politicizing, interested in not just how climate change is impacting on the landscape but how man is adapting to its altering terrain.

Franklin delves into the idea that even national parks – areas of great natural beauty – exist in an artificially protected way, ring-fenced from the march of industrialization and cultivation. In his book The Time of Trees (published 1999) groups of wanderers are pictured walking through serene forests; New York’s concrete towers prod the skyline poking out from behind the leaves of the inner-city oasis of Central Park; and American soldiers sifting through rubble, including a charred tree, in the aftermath of a devastating truck bomb in Beirut – capturing not only man’s impact on the land but the ways in which mankind sees itself in a grand hierarchy of nature, powerfully cultivating his environment, but also somewhat awestruck by it.