After La Haine

As the suburbs overtake cities for population growth, Lorenzo Meloni revisits the Parisian outskirts where La Haine was filmed

The suburbs have been declared the area of largest demographic growth globally. A recent report by The Economist notes that in “developed and developing worlds, outskirts are growing faster than cores. This is not the great urbanisation. It is the great suburbanisation.” In France, Paris’s suburbs are an area of concern, a rich and diverse bed of dissent, and the inspiration for great art. With a history of unrest, the disparity between rich and poor has grown ever wider in these areas, and violence seems to be always close to the surface.

The Parisian outskirts depicted in the paintings, films and photographs of the early 20th century were seen as bucolic places to get away from the dirt and slums of the city, a trope explored by Manet and Renoir in various iterations of the Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. By the mid 20th century French filmmakers, most notably Jacques Tati and Jean-Luc Godard, were taking a keen interest in the changes happening in the French suburbs.

The call of the suburbs is heard acutely by cultural makers; from 2016’s Stranger Things to Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs, Leslie Thomas’s Tropic of Ruislip, Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, and countless others, the city’s outskirts provide the contemporary iconography of the stories of our time. Despite their image as a repository for bourgeois living and its attendant bored youth, the suburbs are in fact diverse and culturally relevant, and they act as a microcosm of wider society.

The suburb of Chanteloup-les-Vignes, in the Western banlieue of Paris, and in particular the Cité de la Noé, provides the setting for the main suburban scenes of Mathieu Kassovitz’s now-iconic 1995 film La Haine. Brutalist 1960s buildings depicted in black and white provided the backdrop to one of France’s most brutal yet human depictions of youth, and inspired scores of image-makers, including Magnum’s Lorenzo Meloni, who revisited the area in 2016.

Pierre Cardo, the local mayor at the time of the film’s making, remembers that he authorised for filming to take place, but on the condition that the exact location would not be revealed. The area had seen unrest and public violence from the early 90s onwards; Cardo was understandably wary of tarnishing his town’s reputation.

These riots – protests of a young generation against dismal living conditions, lack of opportunity and austerity measures – form the backstory to La Haine, which follows three young men for 24 hours after a night of riots saw their friend mortally wounded and held in remand. Angry, disaffected, but likable and funny, Vinz (played by Vincent Cassel), Hubert (Hubert Koundé) and Said (Said Taghmaoui) err though the “Cité” and through Paris; through brief encounters with locals and police the film reveals their rage and social malaise. Hubert’s line “La haine attire la haine” (hatred breeds hatred) becomes emblematic of the film’s stance and gives it its title.

A massive hit in France and beyond, La Haine decisively changed France’s perception of the suburbs, of itself, and ultimately of film-making. In the words of Guardian journalist Andrew Hussey, “in 1995 La Haine seemed to describe exactly what was wrong with France. In one of its blackest years, it seemed both to capture the mood of the country and turn it into great art.”

During jubilatory drinks in Cannes where the film was received with glowing critiques, Cardo’s secret came out and the film’s setting was unwittingly revealed. The consequences for Chanteloup were dire. The film’s acclaim had a proportionally negative impact on the town. A sense of shame and hopelessness pervaded the area, and local inhabitants remember preferring not to disclose their address when applying for jobs so as not to negatively affect a prospective employer’s perception of their application. But the film also highlighted the plight of Paris’s banlieues.

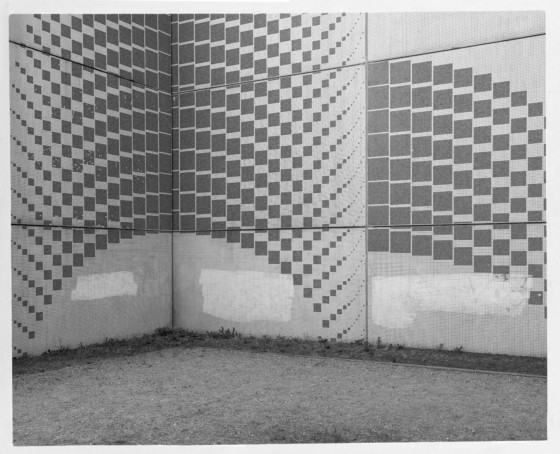

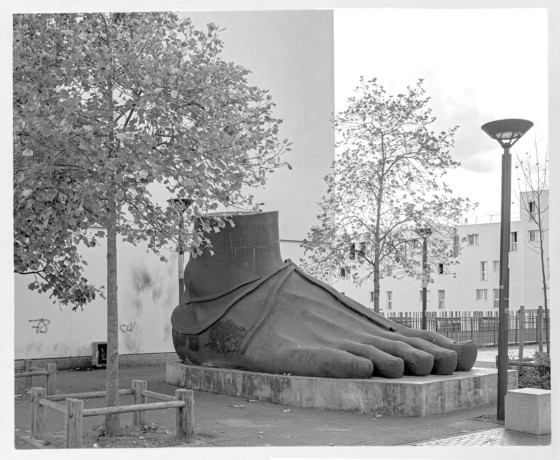

Architect Emile Ailaud’s ambitions for the Cité de la Noé were idealistic, utopian even: the social housing he imagined for several of Paris’s banlieues was original and poetic. He incorporated parks, open spaces and curved, sinuous, shapes to his urban planning, rejecting the rectangularity and linearity that was the architectural norm of the mass social housing of the time. Little did he imagine that his aspirations would form a dedalus which would, decades later, create a propitious setting for drug dealing and clashes with the police, or that the giant frescoes of France’s cultural icons, such as the poets Rimbaud and Baudelaire, painted on the walls of the market square would be perceived as “Orwellian”, in the words of one Guardian journalist.

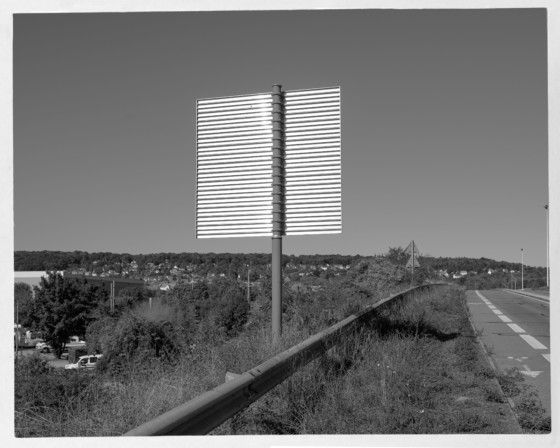

Chanteloup-les-Vignes was one of the first to benefit from a massive urban renovation program which began in 2003. Over a period of over 20 years the town has worked hard to change its image, aiming to renovate the Cité and ease the tensions between local youth and police, increasing funding for education and rethinking public spaces to open them up, building new facilities such as mosques and gyms. These are the spaces explored by Lorenzo Meloni in this photo-essay.

The suburbs were perhaps the culturally-defining architecture of the 20th century, and in the 21st, they remain a visceral reminder of the mixed, segmented societies we live in.

This story is part of The France Project: perspectives on the social, political and cultural landscape of contemporary France. In this ongoing project, initiated in 2016, Magnum photographers explore the background to issues influencing debate in the country in the run-up to the election. See more stories from this project here.