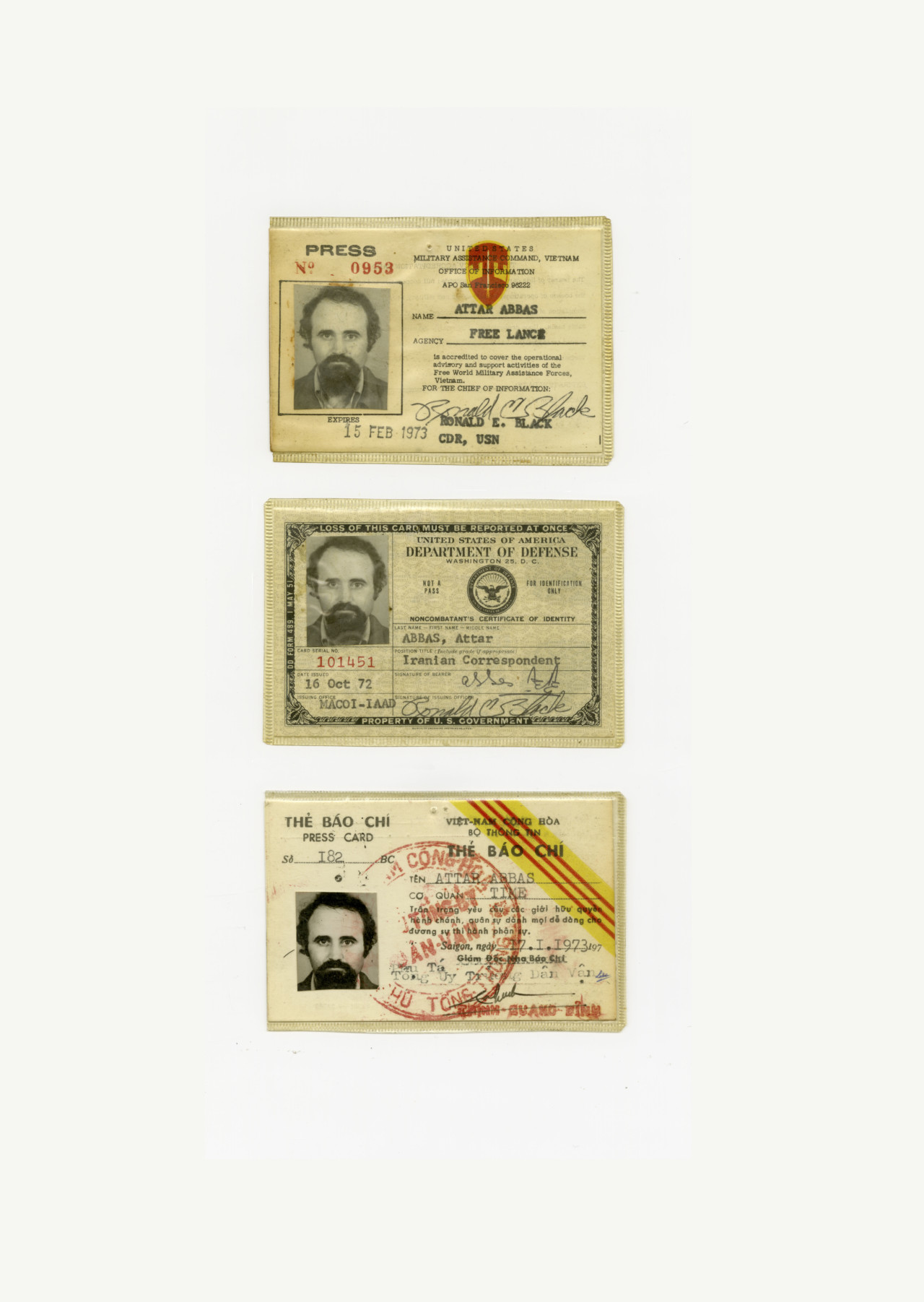

When Abbas arrived in Vietnam in 1972, expecting the conflict there to be drawing to an end, the civil war between US-backed South Vietnam and the Vietcong, a political organization aligned with the Communist North, was only intensifying. Despite assurances from President Richard Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, that peace was imminent, the failure of the 1973 Paris Agreement to garner American backing ensured this was not the case. US troops officially withdrew from the region in 1973, however it was only with the fall of Saigon in 1975, and the establishment of a new Communist regime in the South, that any sort of peace was established in the region. Abbas’ photoessay My Three Vietnams is unique in capturing the final years of the war from the perspective of all sides, with Abbas having gained access to both Southern and Northern Vietnam, and the activities of the Vietcong army in the South.

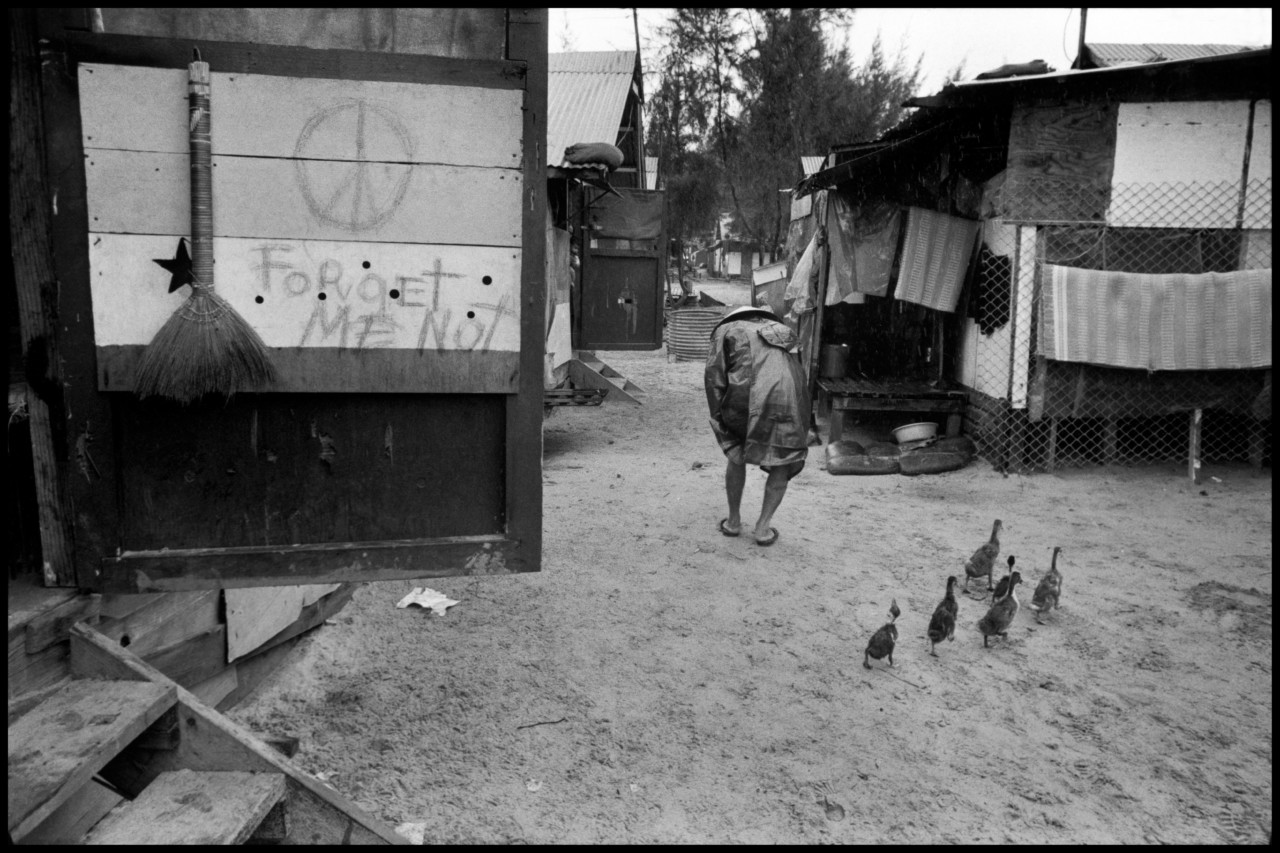

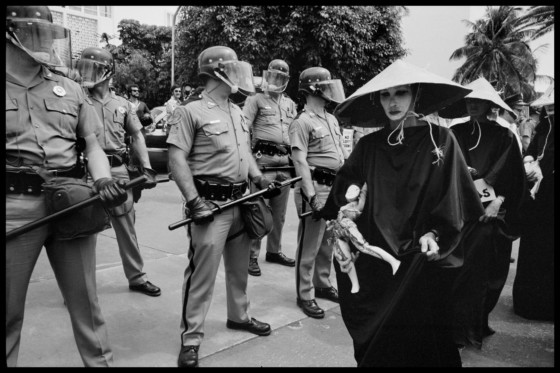

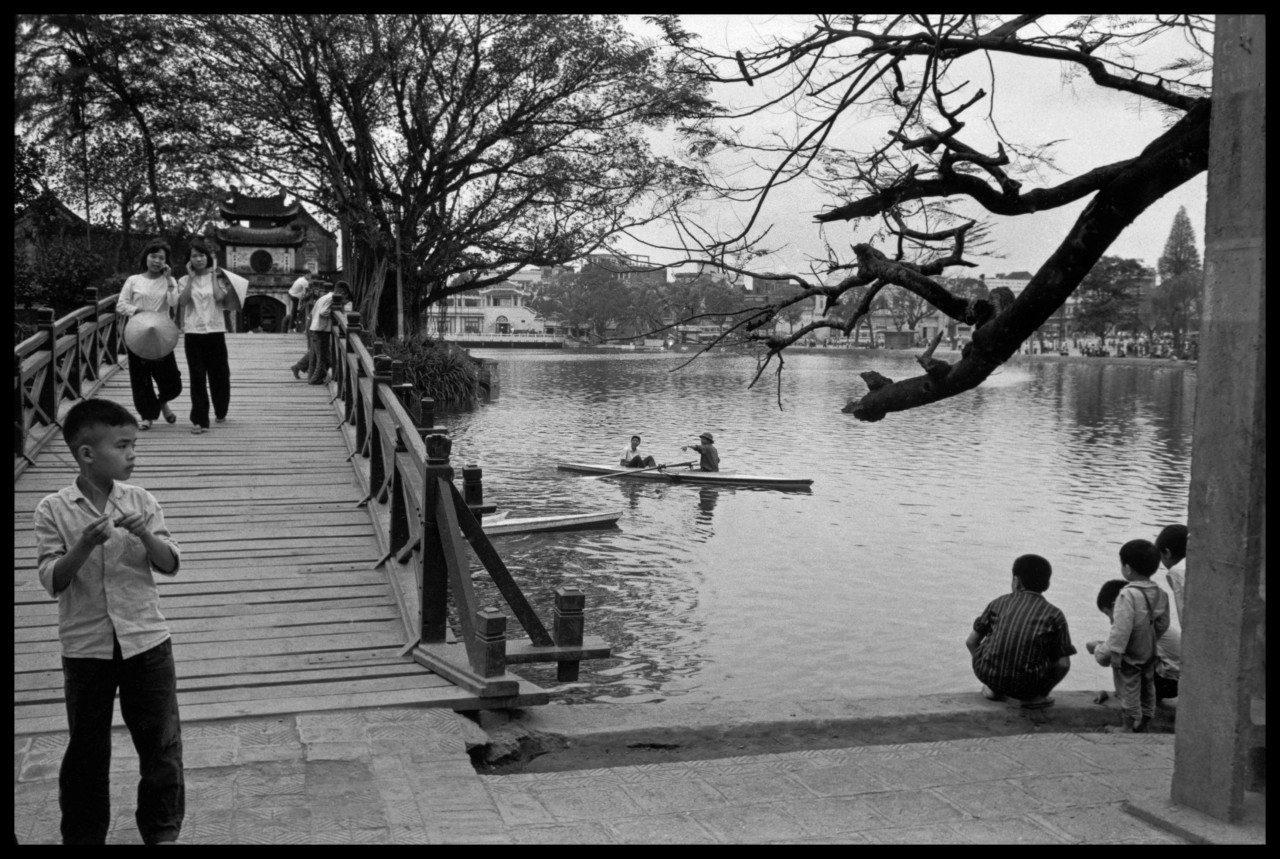

A new book, Vietnam, Forget ME Not, has been released by French publisher, Delpire Editeur. The book draws on Abbas’ work made in Vietnam from 1972 to 1975, as well as his coverage of the anti-war protests in the United States – most notably in Miami. Also in this new perspective on Abbas’ Vietnam is his coverage of the Non-Aligned Movement Summit in Havana, as well as the photographer’s return to Vietnam in 2008. You can learn more about the book on Delpire Editeur’s site, here.

In the following text, taken from Magnum Stories, Abbas writes about his experiences in Vietnam and the development of his own photographic practice.

As a boy I had a heroic image of the journalist: you travelled, you went to war, you covered historical events.

I started out both writing and taking photographs, but I soon found it was more fun taking pictures and like all would-be photographers, I dreamed of covering the Vietnam War. When I became a professional photographer, in 1970, the US troops had already begun to withdraw. It was the ‘Vietnamization’ phase of the war, as they called it, which meant the Vietnamese were killing each other rather than US soldiers. I asked myself what would be worthwhile photographing. The war, Vietnamization and North Vietnam had all been covered. The one thing that wasn’t covered was the Vietcong – this movement, directed by the Communists from the North, fighting the South Vietnamese and US armies. Apart from some militants and some Communist photographers, nobody had actually photographed them. Peace negotiations were underway in Paris, and when in 1972 I heard Henry Kissinger, the US Secretary of State say that “peace is at hand”, I literally jumped on the first plane because I knew this was the moment.

"As every war is about to finish, there is a period when nothing is settled, when one authority has given up its power and the other hasn’t started taking over. "

-

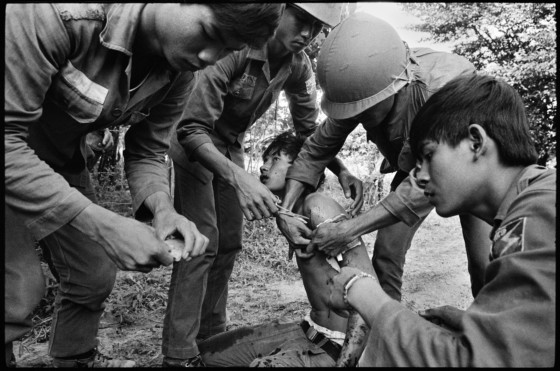

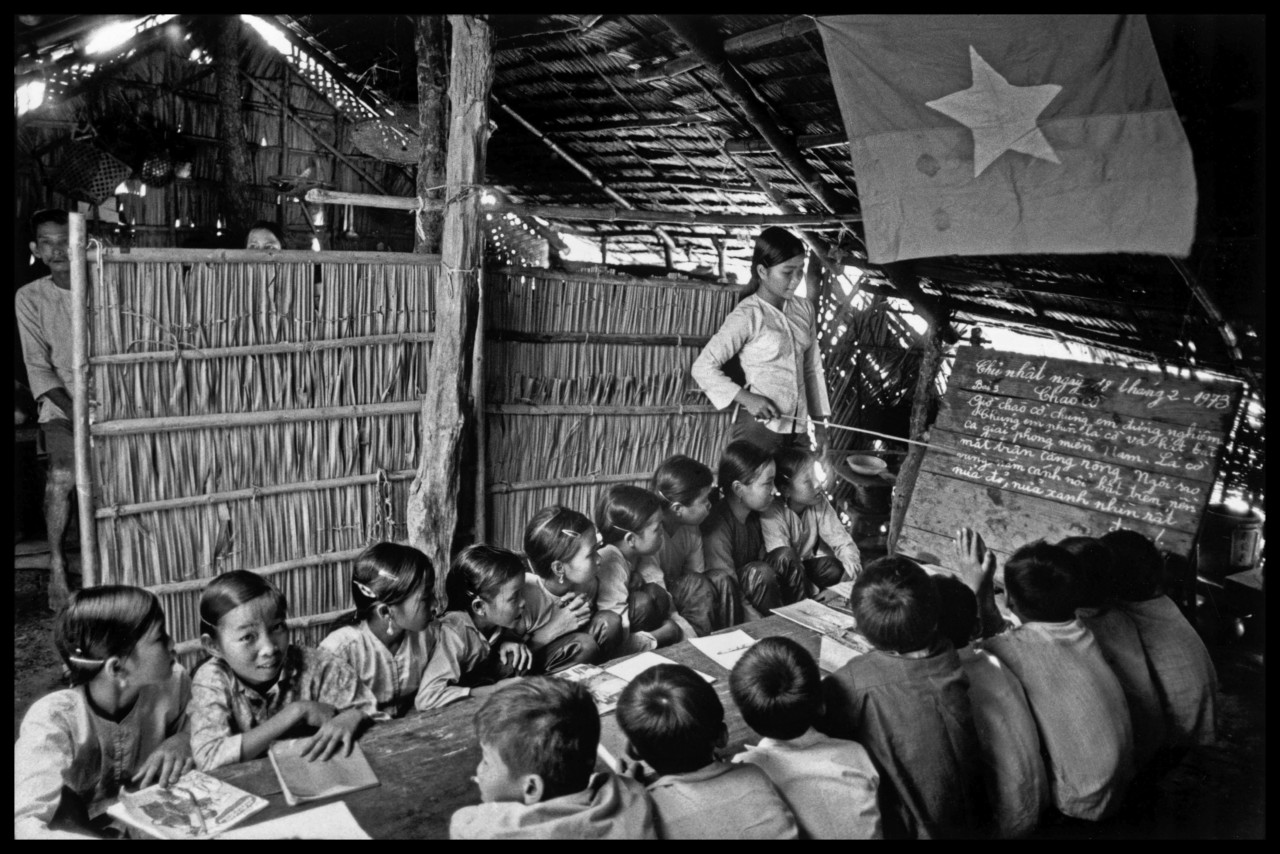

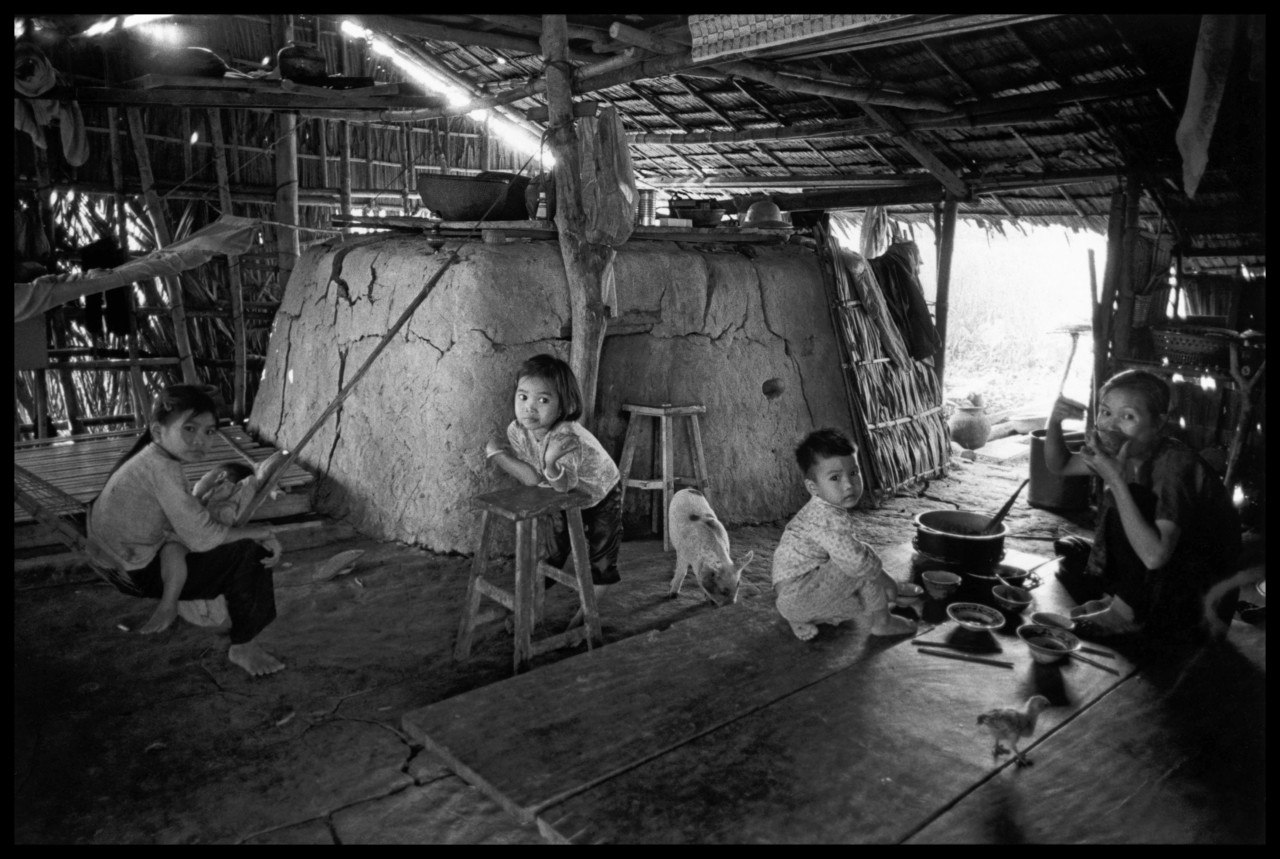

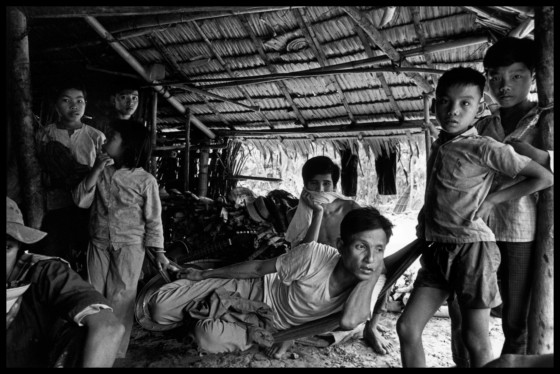

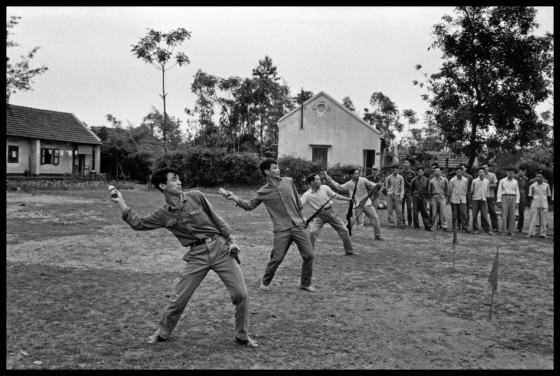

As every war is about to finish, there is a period when nothing is settled, when one authority has given up its power and the other hasn’t started taking over. As I confirmed many times later, in Beirut, in Iran and recently in Iraq, this is when you can really work. But when I went, peace was not at hand. I had to wait four and a half months. I was in my 20s and I could afford to wait. I covered the war, and picked up assignments. When the Paris Agreement was eventually signed, the Vietcong needed to show it was holding territory and suddenly foreign journalists were welcome. I was able to discover ‘the enemy’ that we’d all been dreaming about. I learned that they have schools, they have theaters, hospitals. When I came back to Paris, I used the work I’d done on Vietcong to get access to North Vietnam and got there just before the end of the war which was going on despite the Paris Agreement.

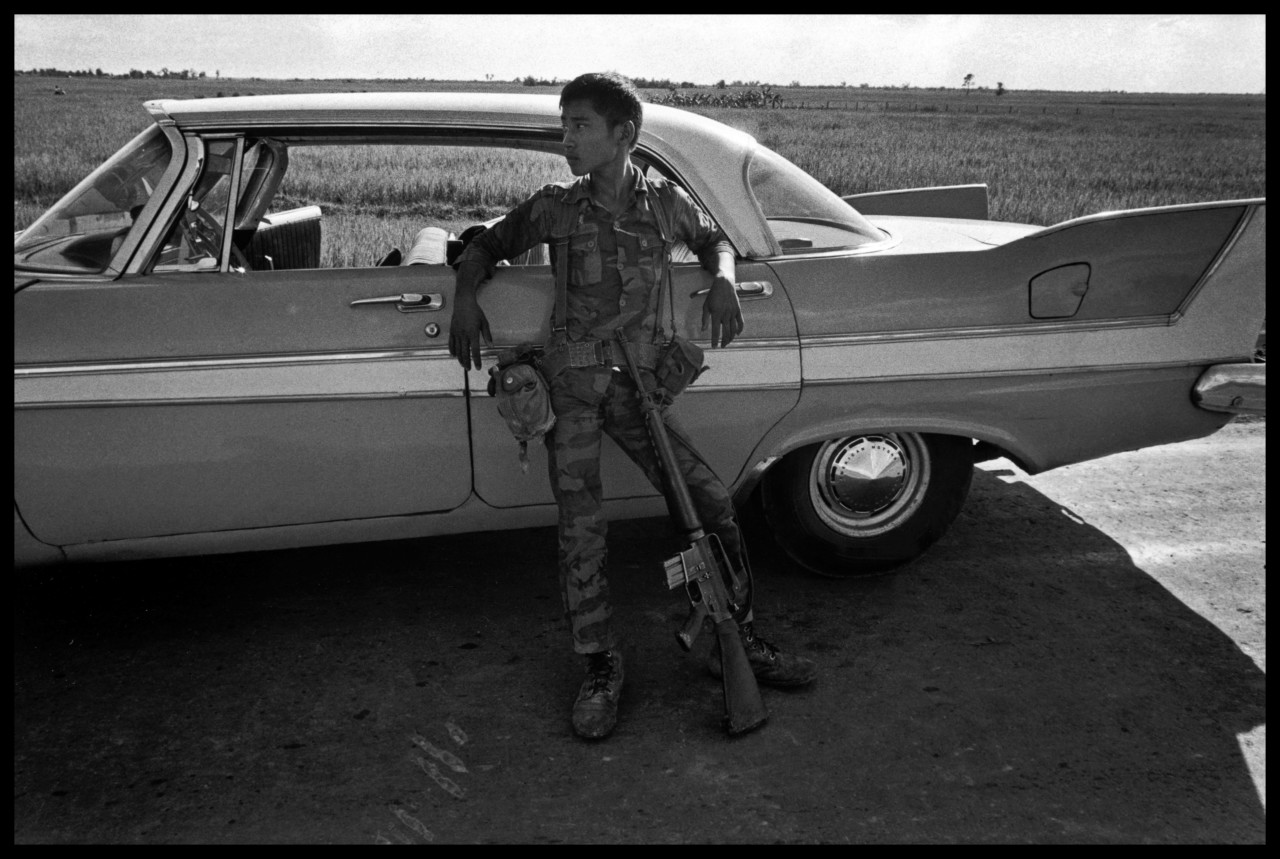

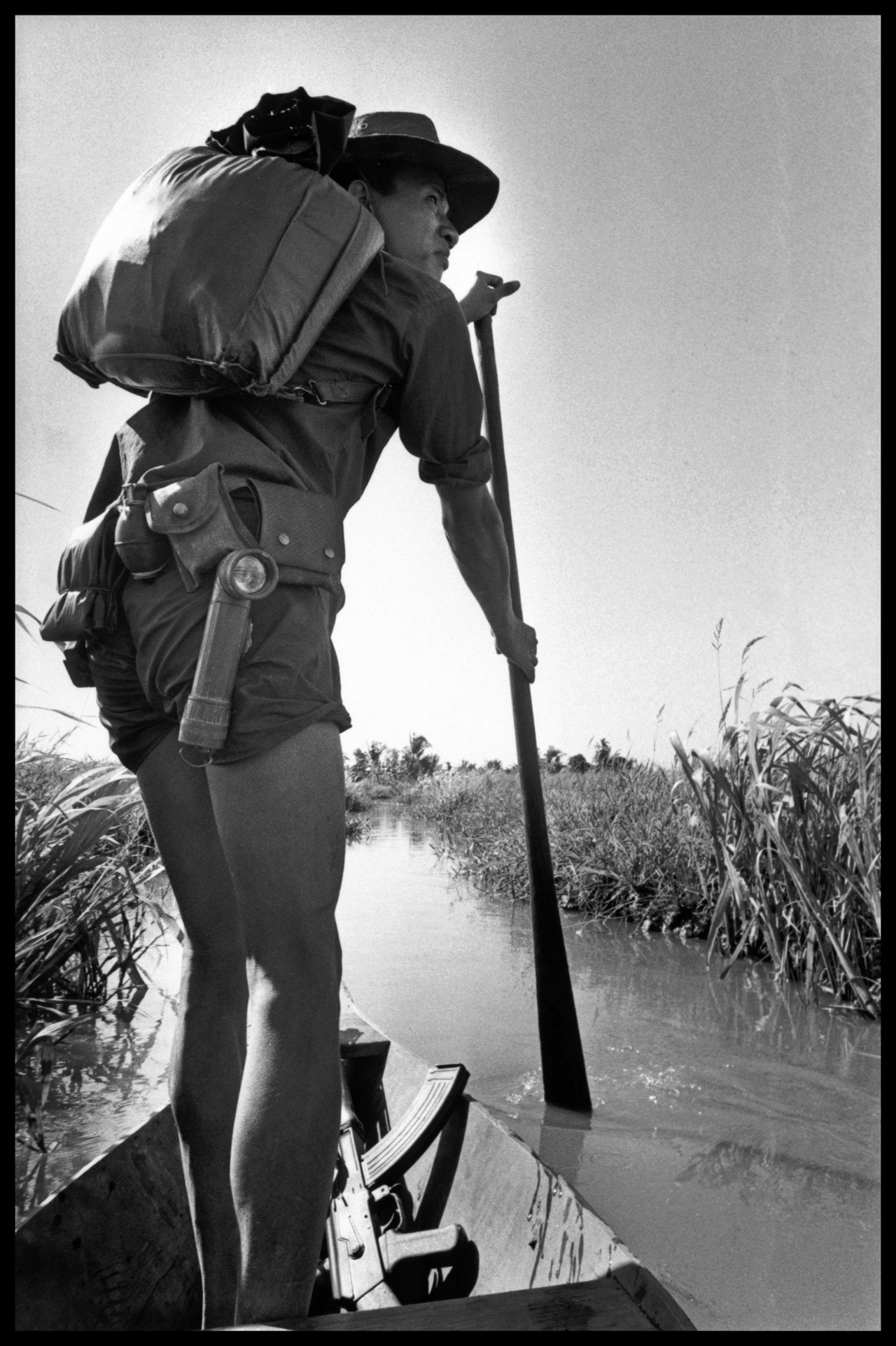

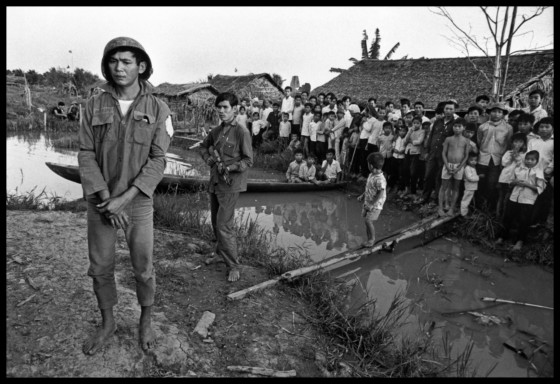

When I started editing my work on Vietnam, two photos became icons of the civil war for me, and helped me understand why the US and its South Vietnamese ally lost the war to North Vietnam and the Vietcong. An ARVN, a soldier of the army of South Vietnam, is equipped and armed by the United States with an M16 rifle. He is resting on a US-built car. A Vietcong guerrilla on patrol in a sampan, in the Delta region of South Vietnam, carries all his belongings in his rucksack and has a Russian-built Kalashnikov at his feet. The Vietcong carries a torch, a hand grenade and his pharmacy around his belt. He paddles the sampan himself. The US-backed South may have had the technology and the hardware, but their opponents had mobility and self-reliance. They could wage a war with everything they needed on their back.

Goksin Sipahiogu was distributing my work at the time, before I suggested he named his agency Sipa because he sometimes signed the pictures under his own name, forgetting the photographer. This was a heroic age: everything was up to the photographer. You worked everything out, you paid for everything, you organized everything. But before leaving for a story, Goksin would bring out his black book and give you girls’ telephone numbers in the place you were going to. That was the kind of relationship photographers had with him. The entire five months I spent in South Vietnam he didn’t send me a cent. He had been selling pictures in the meantime, so there was money coming in. When I got back, I asked him why he didn’t send me some money. He said, “Did you eat when you needed to?” I said yes. “Did you have women when you wanted to?” I said yes. “So what did you need money for? Here it is!” Like a tribal chief, he loved handing out the money himself.

"There are two ways to think about photography: one is writing with light, and the other is drawing with light."

-

Graduating to Gamma, a bigger and more powerful photo agency, the first thing they gave me was a telex card for calling collect. If you wanted to get somewhere, they would give you a list of flights. They would organize your shipments of film, and advance your expenses. Everything was professional. The sales were much better too. When I went to Magnum, it was like going back to Sipa. Here you buy your own plane ticket, you take your own money, your own film. You do everything yourself. I’ve come full circle. But at Magnum they give you the keys to the office.

There are two ways to think about photography: one is writing with light, and the other is drawing with light. The school of Henri Cartier-Bresson, they draw with light. They sketch with light. The single picture is paramount for them. For me that was never the point. My pictures are always part of a series, an essay. Each picture should be good enough to stand on its own but its value is a part of something larger.

I used to describe myself as a photojournalist, and was very proud of it. The choice was to think of oneself either as a photojournalist or an artist. It wasn’t out of humility that I called myself a photojournalist, but arrogance. I thought photojournalism was superior. But these days I don’t call myself a photojournalist, because although I use the techniques of a photojournalist and get published in magazines and newspapers, I am working at things in depth and over long periods of time. My projects can take five years, or seven in the case of my Islam project. My statements are my books. It’s more like the work of a writer than a photojournalist.

Now I don’t just make stories about what’s happening. I’m making stories about my way of seeing what’s happening. There’s a difference. I am interested in the world, sure, but also in my vision of the world. The work comes together not when you shoot but when you sequence it. I go to places, take photographs, cover all aspects of the problem, not just one side or the other, not just South Vietnam but also North Vietnam, the Vietcong. I try to show my point of view about it, not just follow events. I work out what I think about the place and hope that shows in the work.

I realize now that I haven’t changed much as a photographer in all this time. When Magnum recently did a book and exhibition about 1968, they found some pictures that I’d forgotten about, from New Orleans, before I took up photography professionally. I looked at this large print in the exhibition and I realized that today I would take exactly the same picture. I was using a 28 mm lens then, and now I would use 35 mm, but basically, if I had the same situation now, I would take the same picture. It made me proud. I know in the West you have to invent the world every morning, but maybe this is my Eastern background. My perspective on the world has changed, but I’m the same photographer. Thirty-five years of work and I’m doing the same thing!

Photographers often think they have to change their style in order to renew themselves. I don’t have to, because it’s the subject that is different each time. If I renew myself, it’s not in the style. I keep it as simple as possible; I have always used the same photographic approach, the same cameras, the same film, the same 35 mm rectangular format. What I’m dealing with, the problematic, the subject, this is different and therefore my response is different. This is where I renew myself.

"Now I don’t just make stories about what’s happening. I’m making stories about my way of seeing what’s happening"

-

The last time I was really a photojournalist was during the revolution in Iran. I was sending my pictures to Gamma who were doing a superb job at distributing them, and they were getting published everywhere. But I thought, “I’m a photojournalist, so what?” I felt I wasn’t making a statement. Some of the pictures have become icons of the revolution and I hope they will survive me, but it was basic news coverage. Now I want to put events in perspective. After the revolution in Iran I became interested in showing the shock waves of the revolution around the Muslim world. I started making contacts in the ex-Soviet republics of central Asia, and I almost went, but I realized emotionally I was not ready. I had invested too much in Iran; I was still dreaming about it, having nightmares. Instead I went to Mexico. It was a spiritual search, an aesthetic search. I was looking for a language. I went there 11 times over three years. There were no events to cover. The challenge for me was that nothing was happening, but I liked the place, I felt a bond with it, so I photographed it. It helped me develop the language that I used afterwards for my subsequent essays.

There are really two parts, two movements, to the way I work. The first movement is the taking of photographs. That’s intuitive, but my intuition is influenced by my experience, my education, my politics, the dispute I had with my girlfriend the night before. Then when I come back, looking at the the contact sheets and the workprints, I begin the second part: the edit.

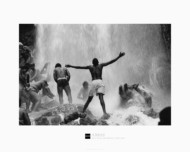

For the photography, seeing in black and white is natural to me. The world may be color but black and white transcends it. When I’m at work, I switch on. I’m in a state of grace. I start seeing black and white. Every tone of color I translate into tones of grey, black and white. It allows you to work on a different level. Since you don’t have to deal with the color of reality, you deal with other things.

When I get back, I edit my contact sheets, have a lot of 13 x 18 cm workprints made and lay down maybe 130 of them on a table. Then I start taking prints away. I show this selection to editors at Magnum, and if there’s a photographer nearby I ask them what they think. It will take me three or four days minimum to come to a sequence of 40 or 50 photographs that constitute the story, which is then distributed by Magnum. The seeds are there of the chapter of a book, even though that will come months or years later.

The most challenging thing for me as a photographer, apart from traveling and taking the pictures, is when I do the sequence, but I rarely think about the sequence when I’m shooting.

"I am among the generation of photographers who believe a picture is sacred, that once you took take it, that’s it: you don’t crop it, you don’t touch it, you don’t fool around with it. "

-

Making the final work, the essay I hope will be printed in book form, is the final stage of the sequencing. It needs six months. I have the prints laid out and first thing in the morning, before I shower, I look at the photographs and go, “Oh, this one goes there, that one there”, and move things around. This is the definitive writing of the essay.

This is all going to change because of the digital camera. When I bring my films back, I see the whole shoot at once, it’s there, and I cannot go back to do anything again. With digital, it’s not only that you see photographs immediately after you’ve taken them, you also start editing there and then, in the evenings when you download on to your computer and you start looking at everything you’ve got, on a larger screen. Thirty-three years after Iran I can revisit my contact sheets and still see everything. The pictures you don’t think important at the time might become important 33 years later. With digital you don’t have the space to keep everything, so you erase pictures. I am among the generation of photographers who believe a picture is sacred, that once you took take it, that’s it: you don’t crop it, you don’t touch it, you don’t fool around with it. You might use it or not use it but that’s something else. With digital, you’re erasing pictures, there on the spot.

I’m too old now to think that people see the same thing that I do. This is the great thing about photography. It’s so enriching. You show the same picture to three different people and you get three completely different responses. And they are totally different from yours. But I make sure people get my point. Which is why words are sometimes necessary, and why all my books have words. They may only be in diary form, just simple writing, but I am saying: read my pictures the way you want to – individual, collectively – that’s fine; read them the opposite of the way I intended, that’s fine too. But make sure you get my point!

This story was published in the book Magnum Stories, published by Phaidon. A very limited number of copies of Magnum Stories are available from the Magnum Shop, signed by Magnum photographers.

Reproduced from Magnum Stories published by Phaidon Press Limited © 2004 Phaidon Press Limited.