Surviving Boko Haram

Paolo Pellegrin’s portraits of former Boko Haram captives in Nigeria depict the still enduring effects of Boko Haram's reign of terror

Nigeria’s northeast is experiencing tragedy on a scale that’s almost impossible to convey to someone who’s never felt what it’s like to lose their family, their home and their livelihood to an ideology that makes executioners out of children and weapons out of women.

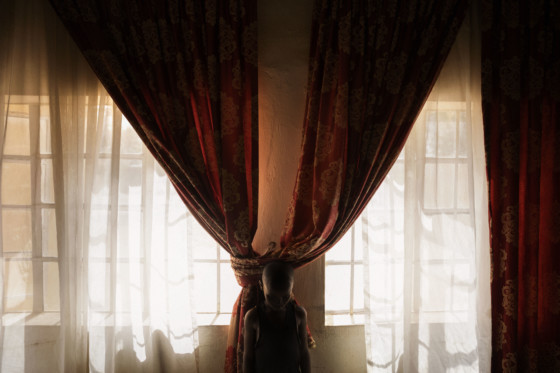

Magnum photographer Paolo Pellegrin’s work manages to capture not only what can be seen, but also how much in this eight-year war goes unseen. This includes the scale of devastation in unreachable villages across swathes of the northeast, the nightmares of a 16-year-old forced into marriage, or the mental trauma felt by a child who watched their parents die in front of them.

No one knows how many have been killed since the eight-year insurgency started. While international organisations stay static by putting the figure at “more than 20,000”, Nigerian officials estimate the death toll is approaching 100,000. More than two million have been displaced. Tens of thousands of civilians have been abducted and forced to become wives, soldiers or slaves for Boko Haram.

Those that are safe are waiting. Pellegrin’s photos capture something of their sense isolation, loss and uncertainty.

In military detention, former Boko Haram captives wait in small, cramped cells for the day they can experience freedom again. In transit centres, where they’re transferred after being released, they wait to be reunited with their families. For the displaced, there are camps to live in while authorities make a ruling to decide they can finally return home.

In camps like Muna Garage, which Pellegrin visited, the residents live in limbo. Walk around any urban setting across the northeast and you’ll spot the displaced: squatting in church yards or sheltering in unfinished buildings; begging in markets or roaming the streets. They are all missing relatives.

In Maiduguri, the city where Boko Haram originated, there’s still a question over who the Islamic militant group actually are. “They’re faceless,” residents will repeat. “We don’t know what they want.”

That means there’s an air of suspicion between the military and locals; the educated elites and the traders; the vigilante groups and anyone passing they don’t know.

Questions also remain over where the next threat might come from: will it be the decommissioned vigilante groups, or could it be the 40,000 orphans who are likely to end up on the streets, some of whom were photographed by Pellegrin.

Even before the insurgency, Nigerians in the northeast rarely dreamed of going to Europe. “People here don’t even like going to the next town,’ locals will say. “They like the simple life.”

Pellegrin’s photos of women undergoing counselling sessions focus on portions of their face, simultaneously distorting their identity and yet conveying their suffering, etched into a forehead, a pair of downcast eyes or the hands that support a heavy head.

In the headquarters of the Neem Foundation, the deradicalisation programme offering counselling sessions, a group of psychologists discussed how to tackle large-scale trauma across a population that can’t escape.

“They’ve gone through a lot and they keep bottling it up. It’s killing them,” a psychologist called Peter Bedheh said of the former captives and displaced people he’s met across the northeast.

Despite this distress, they’d never consider suicide, according to another Neem psychiatrist, Dr Umar. “It is forbidden in their religions and they are conscious of that. They would go straight to hell,” he said, thoughtfully. ‘But outright they will tell you: ‘I have no hope in this life’.”

Written by Sally Hayden, a journalist who has spent time at the Muna garage camp, Muna customs house, the Maiduguri transit centre, and the Neem Foundation.