The Long and Bloody History of Myanmar’s Rohingya Refugee Crisis

Chien-Chi Chang and Chris Steele-Perkins offer a window into the roots of the world’s fastest-growing refugee crisis

Magnum Photographers

Less than five years ago, President Barack Obama stood in front of cheering crowds at Rangoon University and hailed Myanmar’s “remarkable journey” to democracy. But while he praised the Southeast Asian nation’s desire for reform, he also referred to communal violence between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhists in the western state of Rakhine that had left more than 100,000 people displaced that year. “The flickers of progress that we have seen must not be extinguished,” the American president warned.

This summer, those rays of light rapidly dimmed. On August 25, a Rohingya insurgent group launched attacks on a series of security posts that killed more than 100 people. It sparked brutal “clearance operations” by the military, which—according to survivors— has included burning entire villages to the ground, as well as mass rape and murder. Since then, more than half a million ethnic Rohingya Muslims have fled the Buddhist-majority country and crossed into Bangladesh. That’s close to half of Myanmar’s entire Rohingya population. Tens of thousands remain displaced within the country, lacking access to vital humanitarian aid.

It’s not the first refugee crisis to affect the region. As Magnum photographers have documented for more than 25 years, the Rohingya have long faced discrimination and violent repression. Since independence in 1948, successive governments, including the military junta who ruled from 1962 to 2011, have viewed the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. (In fact, some Rohingya can trace their roots back centuries, when thousands of Muslims came to the former Arakan Kingdom, while others arrived during British colonial rule in the 19th and early 20th centuries.)

Under civilian rule, the Rohingya’s plight has only worsened and they are now one of the world’s largest stateless populations. Effectively denied citizenship since 1982, the Rohingya have steadily been stripped of basic rights, facing restrictions on their movement around the country, their education and employment, as well as on marriage and family planning.

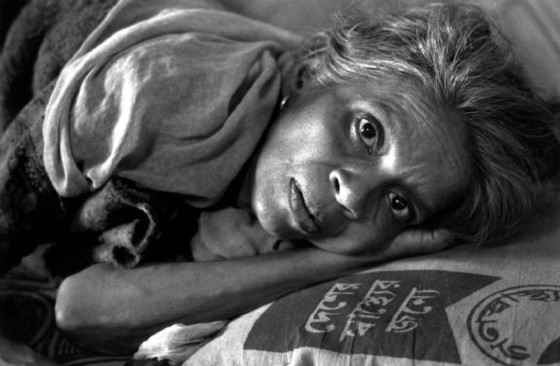

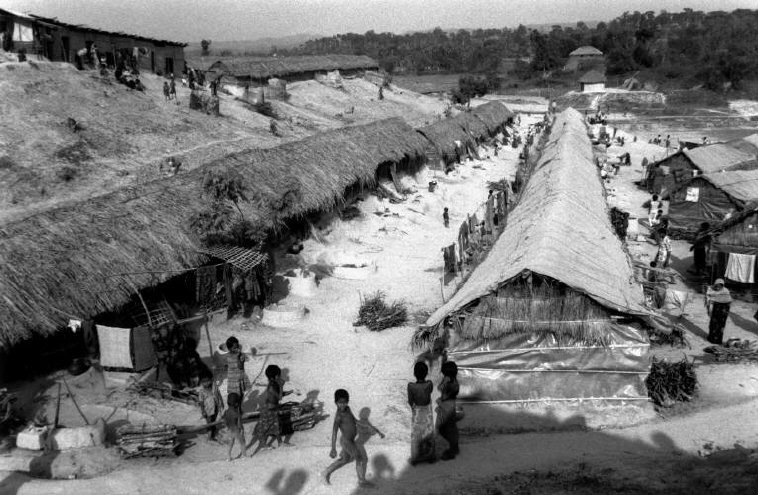

Tensions between the Bengali-speaking Muslims and Buddhists have erupted periodically. Between May 1991 and March 1992, more than 260,000 Rohingya fled the country following human rights abuses by the Burmese military, including forced labor, torture, rape and murder. With the help of the United Nations and NGOs, the Bangladeshi government sheltered the refugees in nineteen camps—but planned to repatriate them as soon as possible. (Then, as now, Bangladesh was not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention.) In 1992, Burma-born Chris Steele-Perkins photographed these refugee flows, which bear a striking similarity to the images coming out of the region over the last year. Most crossed by land into Bangladesh but as with the more recent refugee flows, hundreds have drowned in boats trying to reach Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

While the Rohingya’s suffering has occasionally put the spotlight on Myanmar, the country remains a mystery to much of the outside world. For decades, the junta drew Myanmar into a paranoid isolation, exacerbated by Western economic sanctions. The military still controls key government ministries, while a quarter of the seats in parliament are reserved for the army. Critics have accused Myanmar’s government—led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi—of stifling the free press and backing state mouthpieces left over from the years of military rule.

In some images, the country once known as the “jewel of Asia” appears frozen in time, with hills cloaked in mist and lone fishermen gathering their hauls. Even then, the signs of religious and ethnic conflict are everywhere. While Muslims make up just 4 percent of Myanmar’s population, Buddhist nationalists have expressed their fear that Muslims will take over parts of the country, such as Chin State, to the immediate south of Rakhine. (Steele-Perkins was one of the first outsiders to visit this part of the country, the only state with a Christian majority.)

Chien-Chi Chang’s photographs from spring 2016, after Suu Kyi had just been sworn in as the country’s de facto leader, show a nation caught between repression and reform. In the city of Sittwe on the western coast, we see the result of violence in 2012: more than 100,000 Rohingya live here in displacement camps with little access to food or medical care. That year, the rape of a Buddhist woman allegedly by Muslim men prompted massive religious violence.

Attacks on security posts in October 2016 sparked another wave of ethnic violence—but this year’s brutality seems to have reached new levels. In September, the United Nations Human Rights chief called it a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” Experts worry that the treatment of the Rohingya and the refugee crisis could quickly destabilize the region, fueling cycles of radicalization and retributive violence. Extremist organizations like ISIS no doubt hope to use the Rohingya’s plight to recruit Muslims in Asia for their own ends.

Meanwhile, Suu Kyi has failed to mention or condemn the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya, even as her fellow Nobel peace laureates Desmond Tutu and Malala Yousafzai have urged her to speak out. Five years ago, it looked as though Myanmar was turning away from its history of oppression in pursuit of change and democracy. But today, for the country’s most persecuted minority, those flickers of progress were only ever fleeting.