Although Turkey’s first constitution from 1924 stated that Islam was the “religion of the state,” religion was dropped from the constitution just four years later. In 1937, laiklik (secularism) was written into the constitution and subsequent iterations have reaffirmed that Turkey is a “secular” republic—albeit one that is 95 percent Muslim.

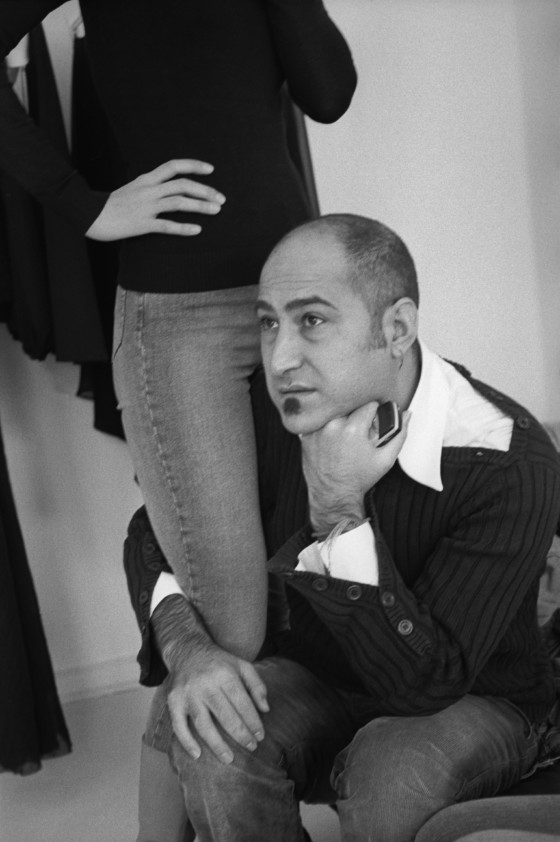

In Turkey today, the aspirations of its secularist founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, have clashed with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s vision of a new Turkey more aligned with its Islamic roots in the Ottoman Empire. In 2013, Erdoğan’s government lifted a ban—in place since 1980—on women wearing headscarves in public institutions, schools and universities. Turkey has built 17,000 new mosques since 2002, enraging secularists, alongside a rise in state rhetoric promoting the adherence to certain religious tenets. As the government has ramped up its use of religious language and symbolism, the rift has deepened between Turkey’s once-powerful secular elite and the more conservative and religiously observant Turks. In the text below, Abbas, who has spent his career documenting world religions, reflects on his documentation of secular Islam in Turkey in 2002 and 2005.

October—November 2002

There are so many photos and statues of Atatürk everywhere, so many citations and slogans eulogizing him in the schools-turned-voting stations, that I wonder why Islamists aren’t more numerous in this country, if only as a reaction to such brainwashing. Kemalist nationalism is a serious thing in Turkey. Atatürk secularized his country by force, and thus opened it up to the modern world, but by replacing the Arabic alphabet by the Latin alphabet he lopped off a whole chunk of his country’s Muslim cultural history. A friend of mine complains that he can’t even read the inscriptions on his grandmother’s tomb.

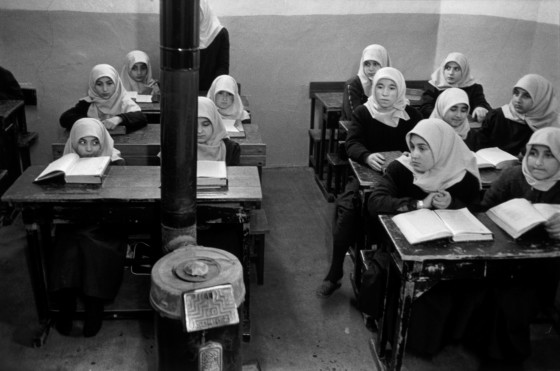

The AKP, the moderate Islamist party, wins the elections with a very large majority. Its leaders do everything they can to try to reassure the European Union, which Turkey hopes to join one day. I’ve always wondered why Turkey preferred to look towards the West rather than the East, and why it should seek to be the poor relation of Europe rather than a landmark in the Middle East and in the vast Turkophone crescent of central Asia. Turkey isn’t just Istanbul, with its tolerant attitudes and all the delights it has to offer. The fact that TV adverts don’t ever show women wearing veils doesn’t mean that there aren’t any. There’s still an undercurrent of religious fanaticism in the country’s hinterland, in Anatolia.

April 2005

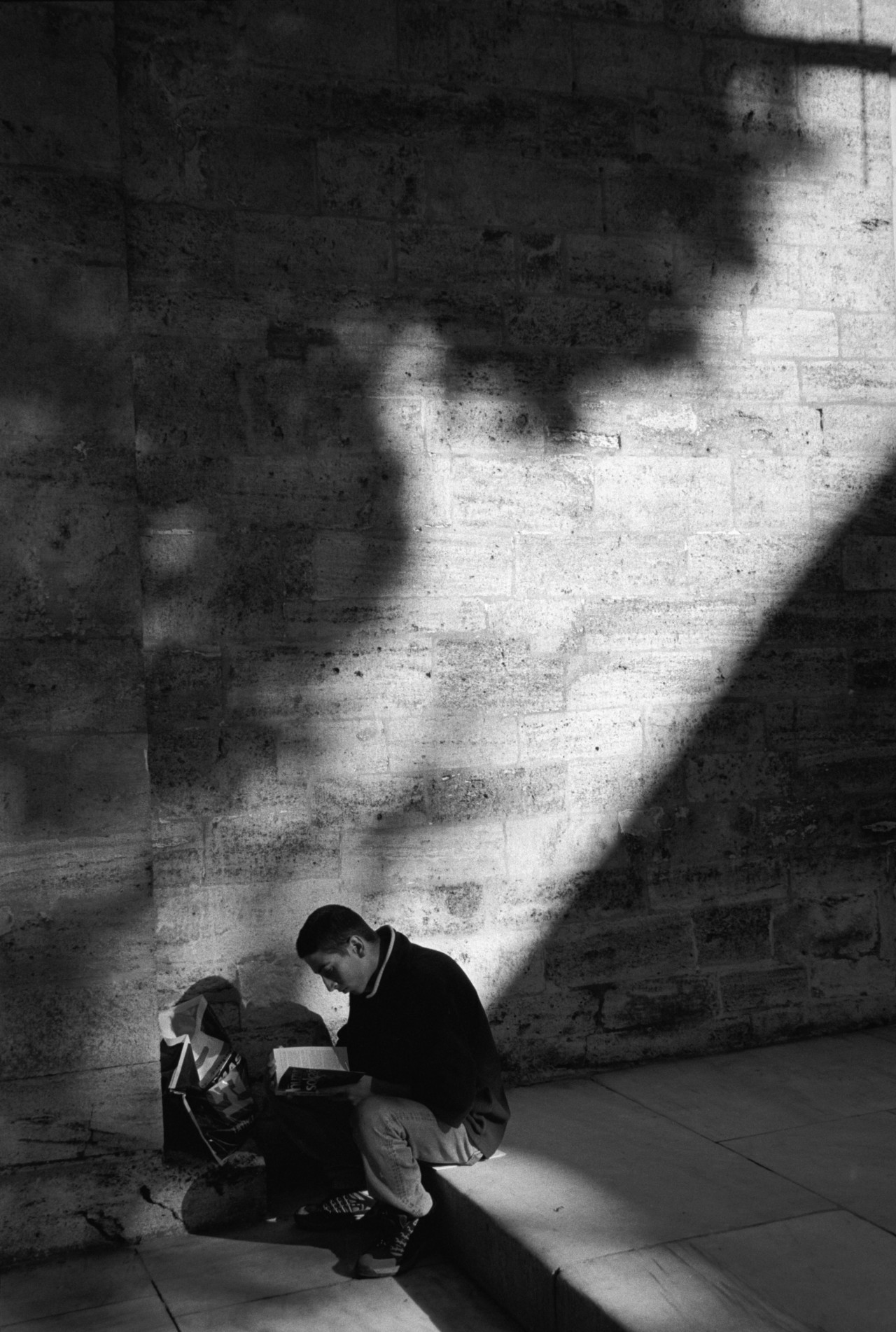

I’m back in Konya, revisiting the tomb of the great mystic poet Jalaluddin Rumi, otherwise known as Maulana. Twenty years ago, his mausoleum radiated a feeling of peace and austerity, encouraging a spirit of contemplation. One of Rumi’s poems extends a welcome to the kafir, the non-believer, the pagan worshipper of idols, as well as to the person who has destroyed a hundred such idols. Today, the place is a museum with all the trappings of nouveau riche wealth, invaded by hordes of Turkish and foreign tourists.

One of the pleasant restaurants surrounding the mausoleum won’t serve any alcohol. My friend Alp and I express our surprise and the waiter nods his head in the direction of the mausoleum to indicate the reason – respect for Maulana. We try to impress upon him that although Maulana was a holy man he wasn’t averse to drinking wine. One of his poems even recommends that visitors to his tomb should only come if they have a drum and a jug of wine in their hand, and advises against planting wheat on top because the body that’s buried there is too saturated with alcohol. The waiter refuses to believe us. So, it seems, that the general bigotry has spread to Maulana’s neighbours. When we go back next day, the waiter announces, rather sheepishly, that yes, we’re right, Maulana did drink. And since we’ve come prepared this time Alp and I drink a few discreet but playful toasts to Maulana, who declared: ‘When I’m dead, don’t look for my tomb on earth, but find it in men’s hearts.’

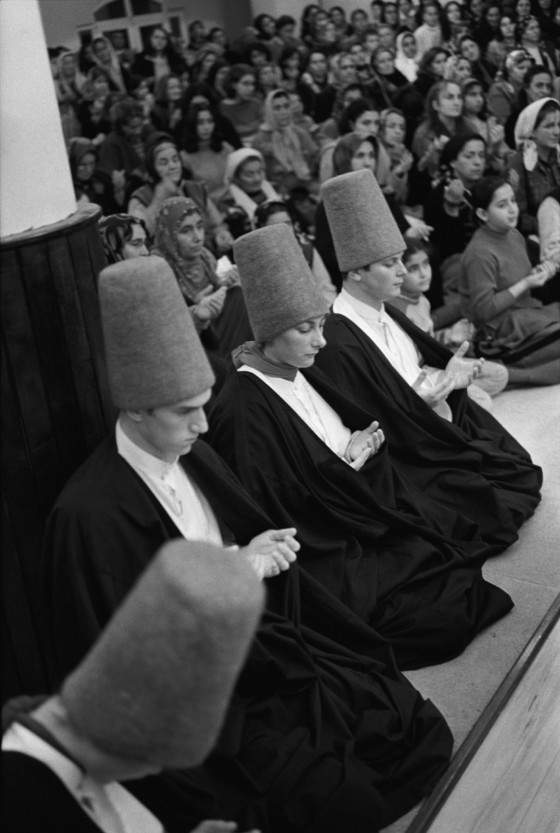

The mouloud, the Prophet’s birthday, is being celebrated in Konya as it is throughout the Muslim world. I’m waiting, along with the local press, in the antechamber to the governor’s office. Suddenly, a delegation of men in suits and ties comes surging in. The Mufti hands the governor a bunch of roses – in celebration of the mouloud – and I’m so surprised I barely have time to take any photos. In any other Muslim country it would be the civil authorities who came to pay the religious leaders a visit, as a mark of respect, and not vice versa. True, a rather grim-looking Atatürk is watching the proceedings from his full-length portrait on the wall. It was Atatürk who forced religious practitioners to quit their traditional dress, and since we are in a public building rather than a mosque the Mufti can’t even wear his turban.

The university of Konya has a modern campus that can accommodate fifty thousand students. There’s a huge room where hundreds of computers are provided for the students’ use, all of them linked up to the internet. This is my own Road to Damascus, converted by the sight of so many computers (no doubt with a bit of help from a malicious Maulana). With all this glorious modernism on display, why take seriously the rearguard action of a bunch of over-sensitive religious leaders anxious to keep their schools under wraps? In contrast with Reza Shah, who modernized Iran without secularizing it – though (let’s not forget) the Shiite mullahs were a great deal more powerful and better organized than the Turkish Sunnis – his contemporary Atatürk succeeded in implanting secularism in his country for good.

The Europeans may never allow Turkey to join the Union. But ought Islam to be used as an argument to justify this refusal?… and then came Erdogan!