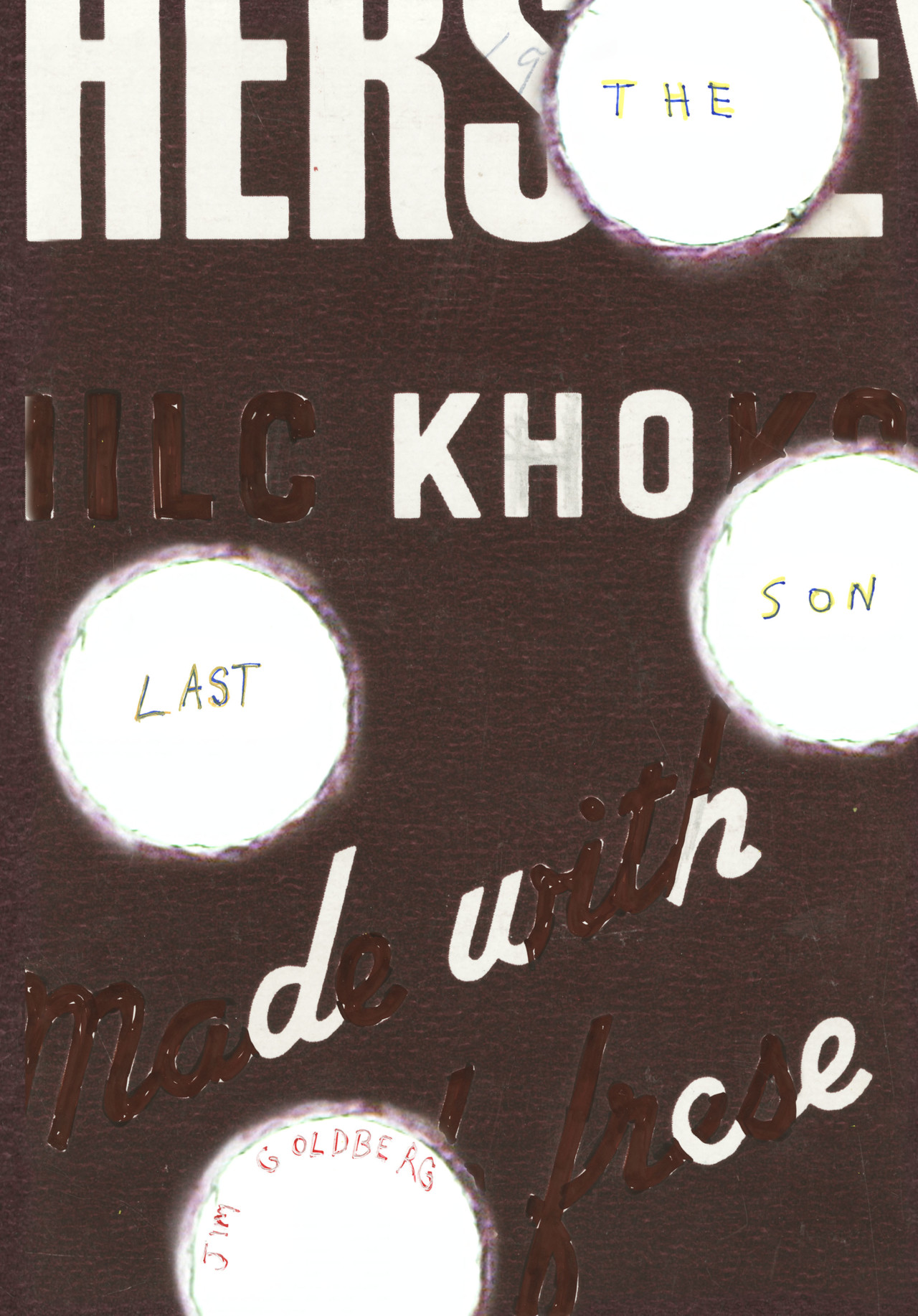

The Last Son

Jim Goldberg discusses his bildungsroman and charting his evolution as a photographer with Joel Sternfeld

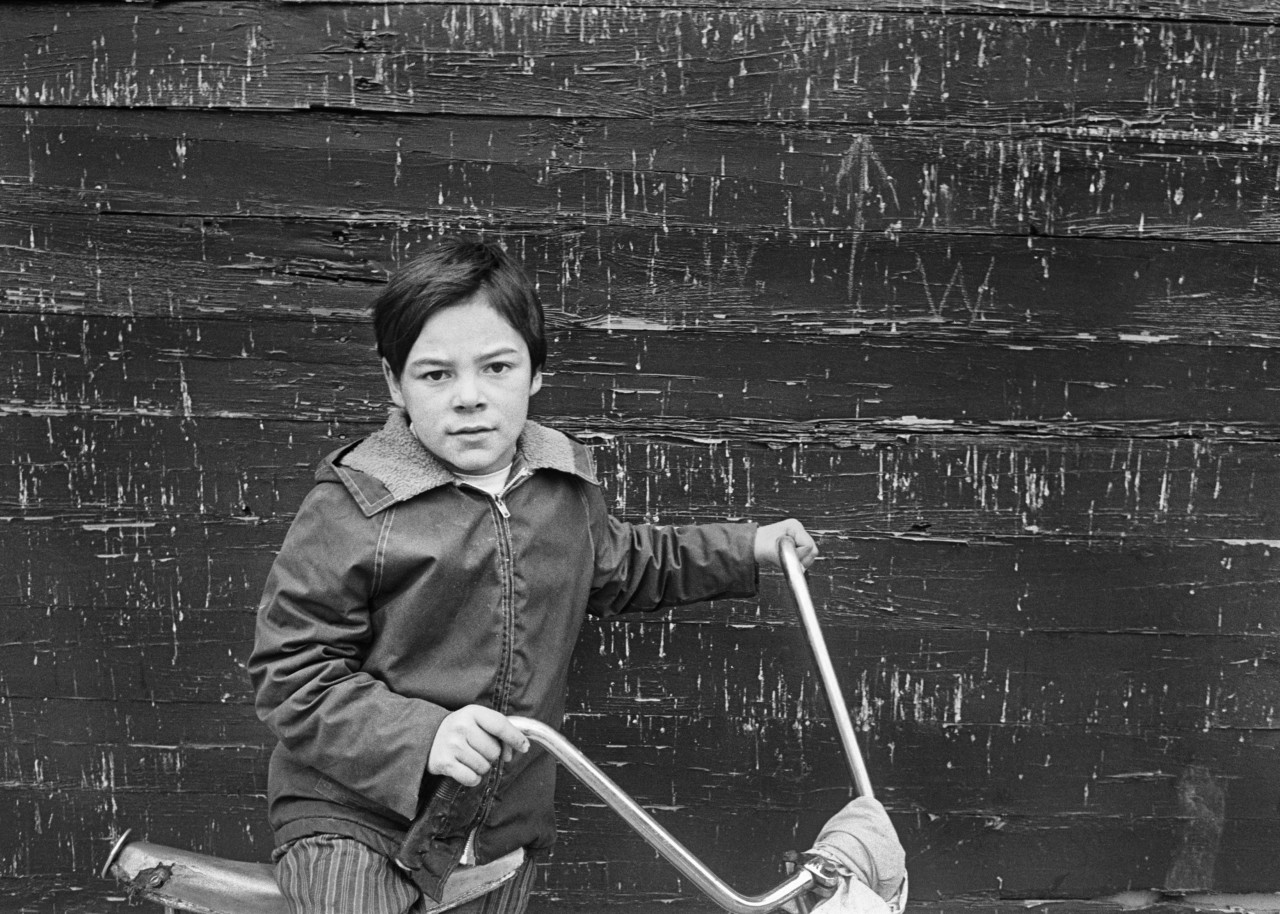

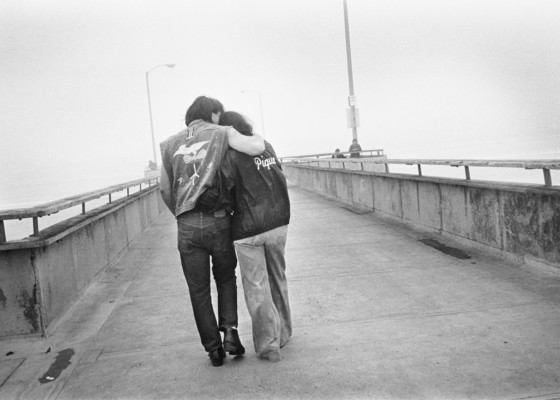

Ever since Jim Goldberg published his seminal 1995 work, Raised By Wolves, which follows the lives of runaway teenagers over a decade, he has established himself as a powerful and unconventional storyteller. But Goldberg saw himself as a runaway too—an outcast in his own home. He has previously commented that “I didn’t really fit in to my family as much as they wanted me to and I think that led me eventually to photography.” In The Last Son (2016), the second book in a three-part series published by Japan-based independent house Super Labo, he becomes the subject—weaving together the story of his formative years with the dreams of his father, who ran the family business of wholesale candy distribution in New Haven.

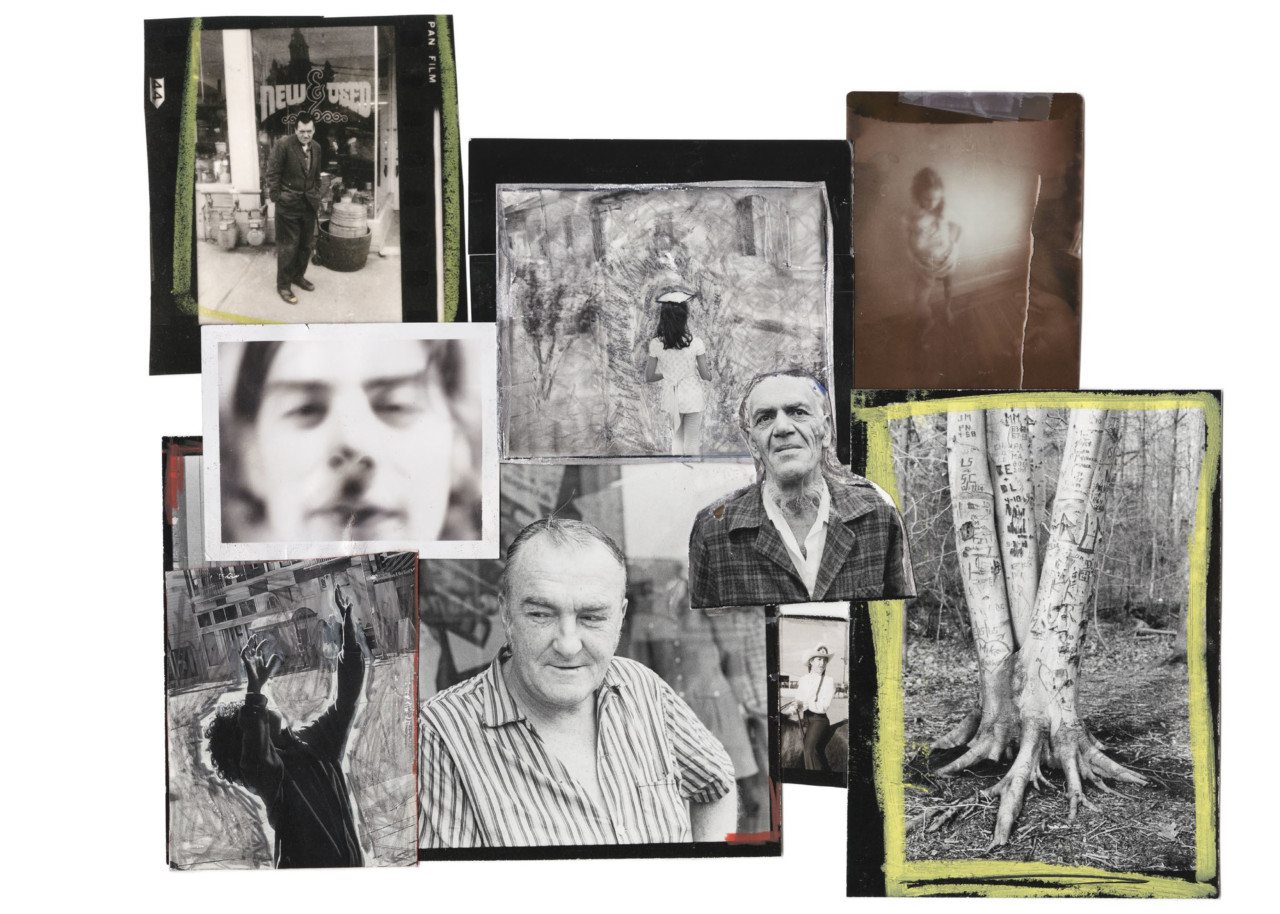

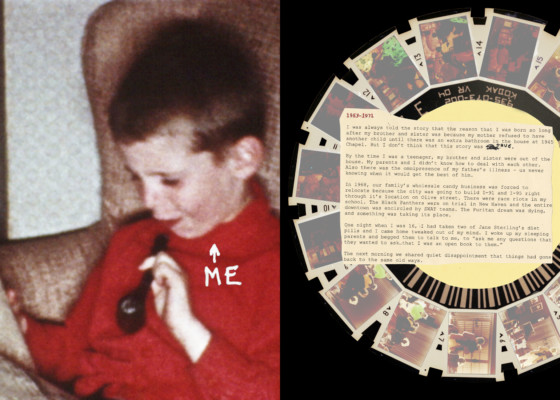

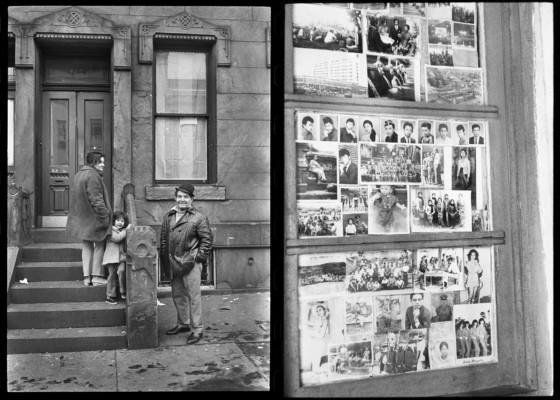

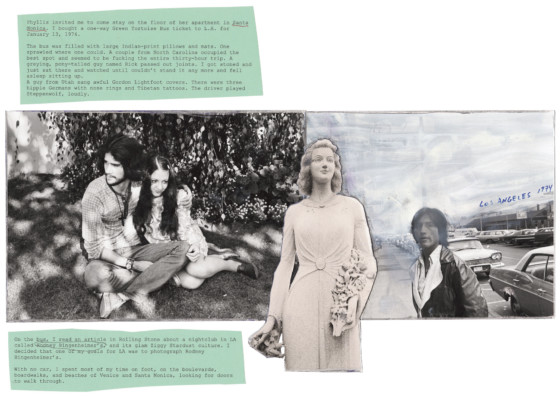

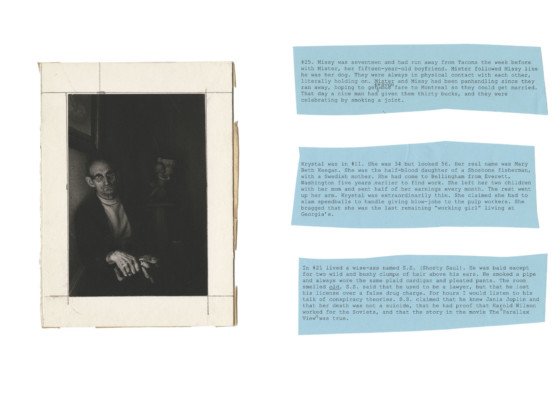

The Last Son is conceptually inspired by Goldberg’s recent revisiting of Rich and Poor, which documented the lives of two economic classes in 1985 in San Francisco. In 2014, Golberg remade the work for Steidl, examining more closely the influence of his early years on the work. Described by Super Labo as a “sculptural collection of overflowing pages,” The Last Son functions as a kind of visual journey through Goldberg’s archives, tracing his growth as a photographer. Images are often accompanied by handwritten text on or over the image; sometimes they are collaged together. Other pages show home movie stills and typewritten anecdotes.

A similar kind of presentation—using collaged archival material and Polaroid portraits—is deployed in Goldberg’s latest book, Candy (2017), which he has called a “photo-novel.” As The New Yorker’s Nicholas Dawidoff writes, “this unkempt approach befits Goldberg’s attempt to describe the many crosscurrents coursing through the unequal city [of New Haven].”

Dawidoff continues: “Across his roving career, Goldberg has combined his gritty, impassioned idealism with a cool professional ability, in the unfolding moment, to see things exactly for what they are.” In The Last Son, where Goldberg revisits memories of being the youngest son, born long after his siblings and confronted with a chronically ill and depressed father, this coolness manifests in a matter-of-fact tone; as Goldberg grows up and discovers photography, he gains confidence about the direction of his life.

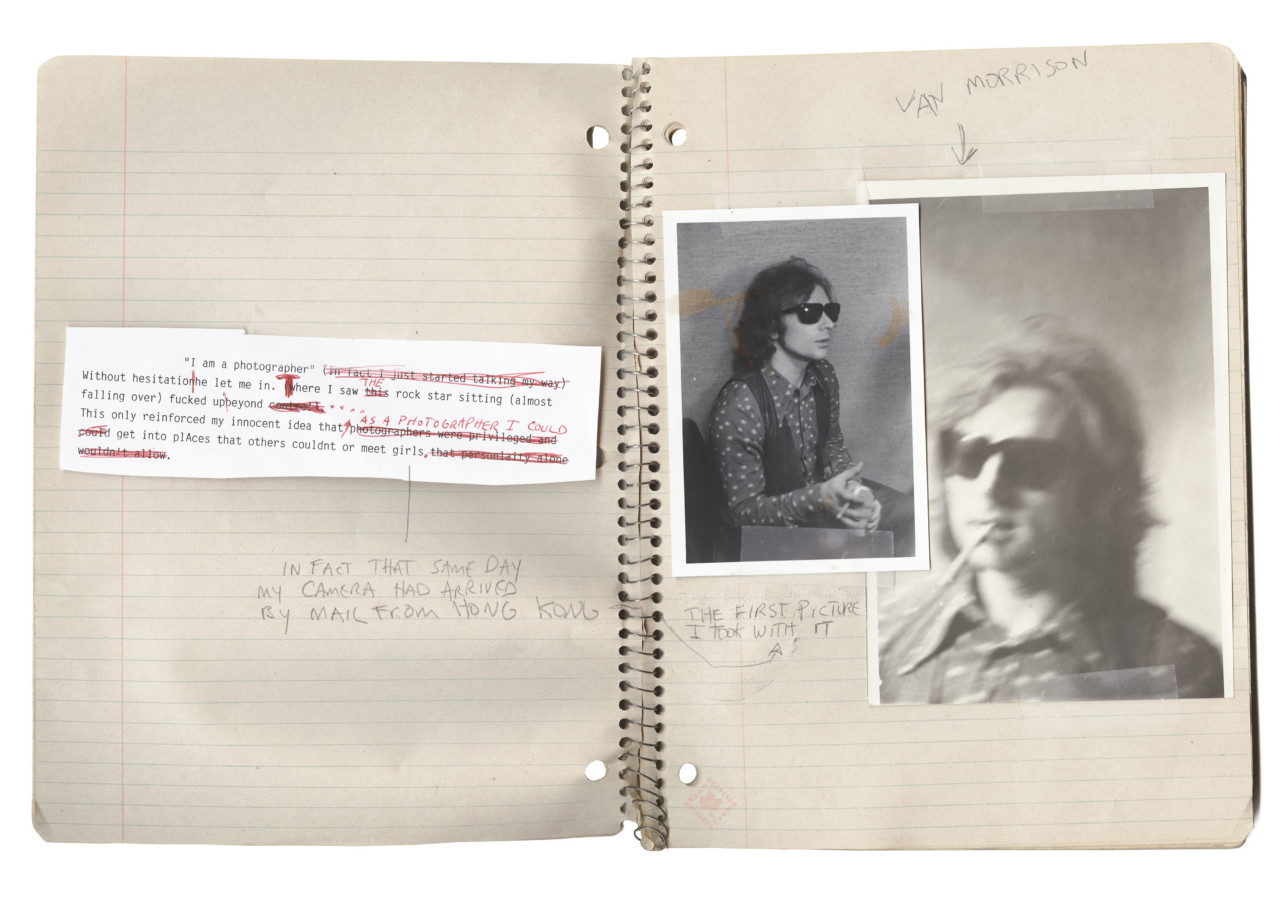

“Being a teenager was terrifying for me, but once I found photography, I dove in deep,” he tells Joel Sternfeld, the color-photography-pioneer known for his documentary projects on American life and culture. “I wasn’t alone when I carried my camera. It was not only a badge of courage; it was an entry point into new worlds.”

Sternfeld spoke with Goldberg for an interview published in Let’s Panic in fall 2016. Read the conversation between Goldberg and Sternfeld below. (It has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Joel: I find the book really compelling. The narrative flow is touching. Where it leaves you — I don’t want to give away the book- but it just leaves you panting for more.

Jim: Well, thank you. Not many people have seen it, so this is wonderful to hear.

Joel: Well, there is a trope in photography of emphasizing a pivotal year or two. There are a number of works that follow that trope, but this one does it particularly well. So let me ask you this— the style of it— were you working in the graphical style that we see in this book back then? I don’t mean just the photographs, but the entire form.

Jim: You mean the way I montage?

Joel: Collaging in the diaristic style. Was that part of your vocabulary back then?

Jim: It was. It was something that I enjoyed doing, and that seemed to work for me. At that point I was still trying to figure out what making a photograph was all about. So I would often make these things, these collages, as a way of almost saying, “When I took that photograph, I wish that I had taken a picture of this, or of that,” you know? It was a conscious way for me to reconfigure my work into a new image or sequence, or somehow use the images to refer to where I was, actually or existentially.

So yes montaging was indeed part of my practice at the time, always with a deep desire to make objects. I often say that I wish I’d become a sculptor.

Joel: That’s interesting because I’ve always maintained that photography has perhaps its strongest relationship to sculpture. People always want to link it to painting. But because I think the photograph tends to deal with the object in space —

Jim: Exactly. I agree, in space. I keep a list of all the sculptures I’d like to make. I don’t know where that list is, but it does exist. It’s actually pretty long.

Joel: So what about the markings?

Jim: In this book, the markings take many forms. For example, I might take a contact sheet that I marked on with a grease pencil back when I printed it, and then cut that up, scan it, and then make a print. I might take that print and combine it with another contact sheet with a different kind of marking on it. Perhaps then I’ll draw on top of that. It’s additive and I will rework these things many times until they feel right, or done. That is the best way I can explain it.

Joel: I see that you were in Boston in about ’73 or so?

Jim: I think so.

Joel: Nan [Goldin] and Mark [Morrissroe] were there, no? Did you have any contact?

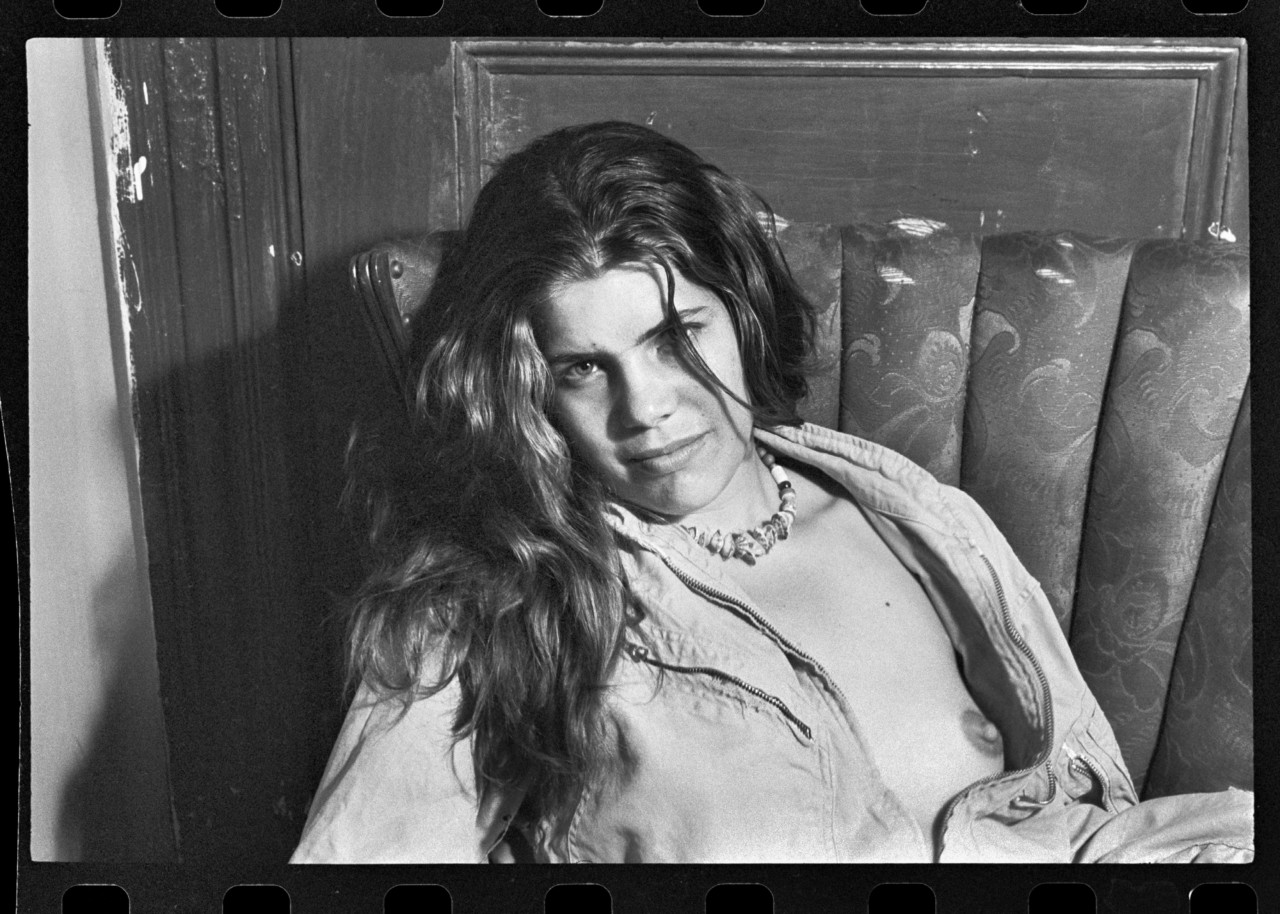

Jim: Nan and I are good friends now, but back then we were in different worlds. We have since acknowledged that it would have been excellent if our paths had intersected then. Our visions of the world, and our questions and concerns about it, were closely aligned.

Joel: What made your worlds different?

Jim: My experience then was mostly internal; I was alone in myself, while Nan was part of a subculture. I was thinking about both of our work this morning, and how it ended up intersecting. There was certainly a sense of alienation from mainstream culture that we shared.

My imagery in The Last Son was a precursor to Raised by Wolves; in it you can see hints of the reasons I later went on to do that project.

"I think that in some ways, all any of us are looking for is an intelligent witness to our lives. "

- Joel Sternfeld

Joel: I noticed that. I noticed that you were a runaway, and Raised by Wolves is about runaways.

Jim: Yes. The title of the book, The Last Son, comes from the idea of a bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story. I always thought of myself as the “loser” at home. I was the youngest, and the rumor among the family was that I was a mistake. My sister and brother were older and during my adolescence they were already out of the house. I felt like I was left alone with my parents and I wanted out. Back then I couldn’t comprehend how dysfunctional it really was at home.

I know I wasn’t alone in feeling this way. If I had been born twenty years later, I probably would have ended up on the streets. I was your typical, “no one understands me and I don’t fit in” kid. I begrudgingly followed the rules, but I was attracted to the idea of running away, of starting a new life and reinventing myself somewhere else.

Joel: I love that the book is so filmic that the Watergate hearings function as a backdrop. I remember that time. Anybody who was alive remembers that so vividly, hanging on every senator’s word.

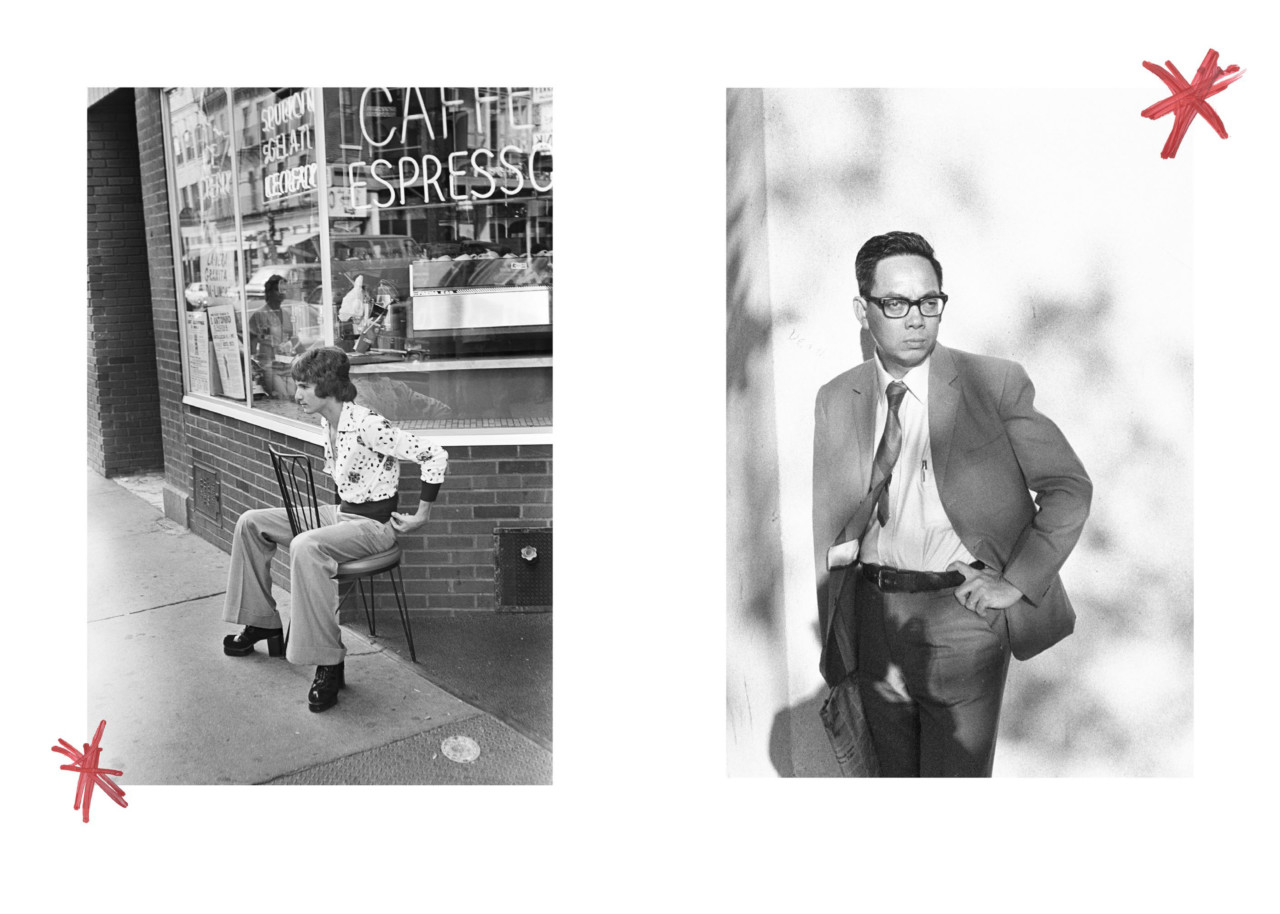

Jim: Yes, I’d come out of the darkroom and see the television on, and the people around it, fixated on how the story would unfold that particular day. I’d then go back into the dark and think about what was going on outside, what was happening to our country. That was when I started thinking more seriously about becoming a “photographer.” I was falling in love with the medium and completely immersed in it. I met girls and went to lectures and lived in weird apartments in Boston and Cambridge. It was an interesting and exciting time in my life.

"To have a camera opened doors for me that I wouldn’t have entered otherwise. It was a way for me to express things for which I had no words, to attend to things that puzzled or intrigued me."

- Jim Goldberg

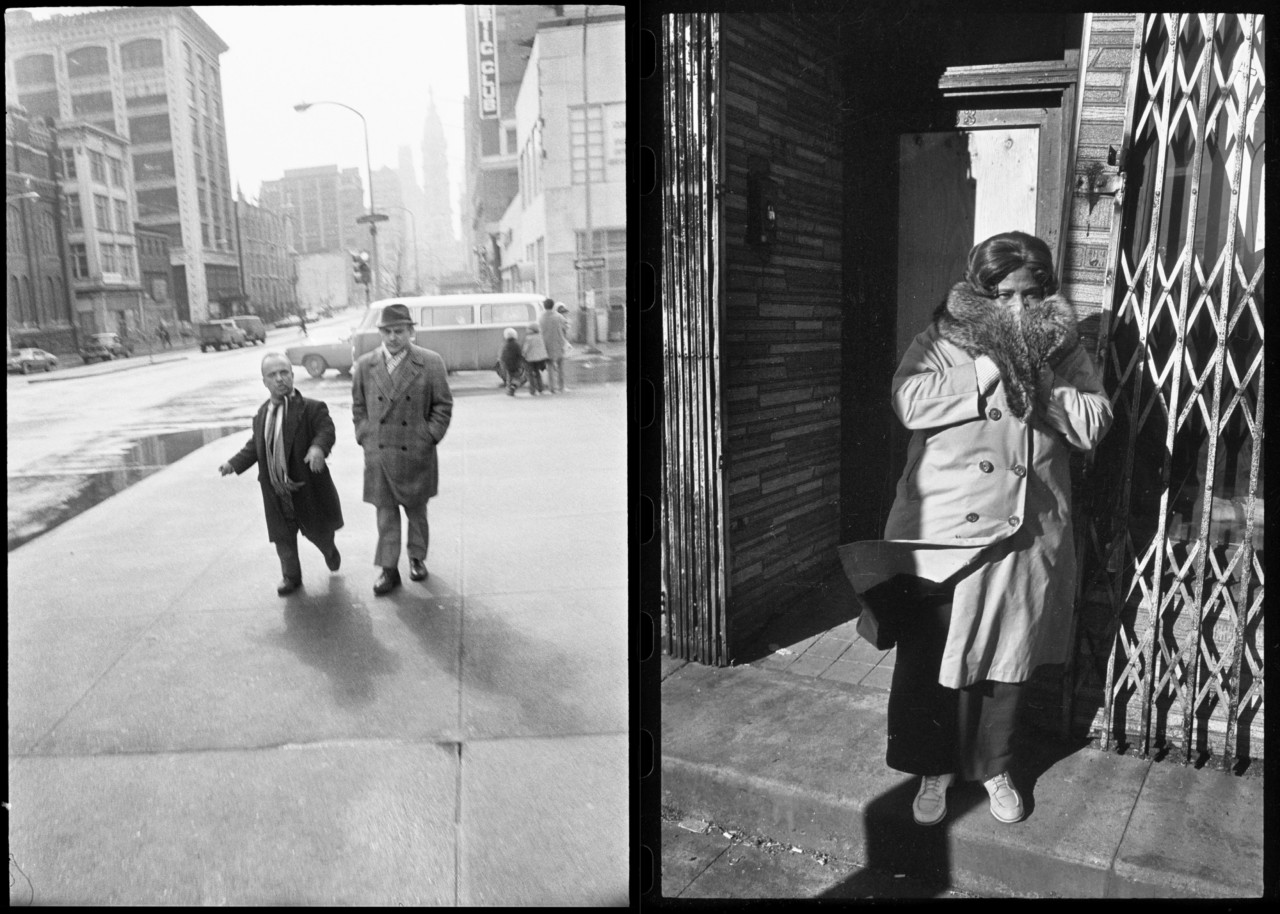

Joel: Well— let me preface the question— what I like about the pictures from that period is you seem to be photographing – to borrow a phrase – with a very democratic eye. The pictures are non-hierarchical. They’re not particularly narrative of anything and especially not of the normal, mawkish points that can be made by a beginning photographer. You seem to arrive at this uninflected, everything-is-interesting, the curtains of perception are lifted style at a very early age and a very early age photographically. How did you know that everything was interesting?

Jim: I know that it’s such a cliché, but to have a camera opened doors for me that I wouldn’t have entered otherwise. I wasn’t alone when I carried my camera. It was not only a badge of courage; it was an entry point into new worlds. For example, it gave me license to approach strangers, especially people who were somehow different; it was a pass for entry into music clubs that I didn’t feel I belonged in. It was a way for me to express things for which I had no words, to attend to things that puzzled or intrigued me.

And I became more self-aware. So in terms of your point about my “democratic eye,” I think that this was real, and that it’s still real. Surely now my eye is more trained and refined, but everything is still interesting to me.

Joel: Can I just offer an observation, not a question? To me, it looks like you arrive in photography somewhat fully-formed. I’ve written this and I have this thesis about Stephen Shore, which is the giant, baby pigeon thesis. If you’ve ever looked on the streets, you never see a baby pigeon. You never see a small pigeon. They stay in the nest until they’re full-sized. Then one day, the parents kick them out and they spend about an hour learning to fly. And then on the street, you see nothing but pigeons all the same size. But amongst them are some juveniles- giant, baby pigeons. And that’s what sort of stuns me about Stephen is at this very early age, he seems to have been fully-formed as an artist, as a great artist. And you seem to be another giant, baby pigeon. Do you accept that label?

Jim: The label, I don’t know. I mean, thank you. I’m touched that you would feel that. Perhaps you are able to see this early work more clearly than I can, because I’m so close to it. But if you see me as a giant baby pigeon, well, that’s a label that I would live with happily.

Joel: It feels like a mature work. And I think your life must have been much more tentative and much more frightening than the book.

Jim: It certainly was. At the time there was so much that was suppressed, and even more I just couldn’t grasp, but it was there. Being a teenager was terrifying for me, but once I found photography, I dove in deep. I became absorbed in my new-found world.

"I think your life must have been much more tentative and much more frightening than the book."

- Joel Sternfeld

Joel: So aside from this great passion for photography, what else is sustaining you throughout these very tentative years?

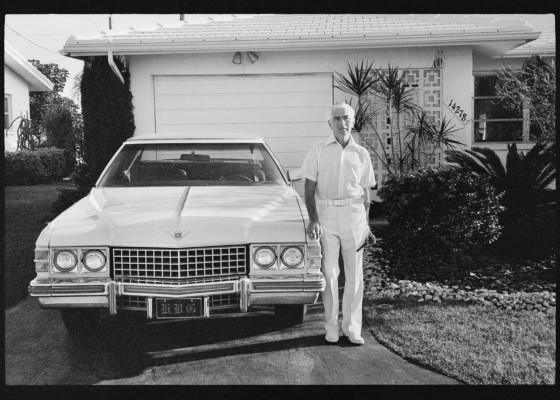

Jim: Well, things got less tentative the more time I spent away from home. I moved west to the upper reaches of Western Washington. My parents had left New Haven and retired to Tampa, Florida. So at that point I was about as far of a distance from my parents as was physically possible.

Joel: So you’re hitchhiking around the country. You’re all-consumed by photography…

Jim: Yeah, and girls, and growing out my hair.

Joel: So you mentioned that one of your grandfathers was a socialist.

Jim: Yes.

Joel: Were you a red diaper baby?

Jim: I wish. I was a Kennedy democrat baby.

Joel: So where does your social consciousness come from? The early pictures in this book are sympathetic in that same unsentimental way that the pictures in Rich and Poor are. Where is this coming from? What’s the source?

Jim: A couple of years ago, I began to revisit my archives and the work that would become The Last Son. Right around that time, I received a fellowship from the Yale University Art Gallery to do a project about New Haven. Both of these projects touched on my youth and allowed me to revisit these early experiences.

My social consciousness dates back to these early days. I grew up in a progressively-minded community. My uncle was a notorious Communist, and our Rabbi was marching in the front lines with Martin Luther King, so at a young age I was introduced to ideas about inequality. I held a deep belief that things could be different, that injustices could, and should, be righted. American Exceptionalism in action. We were taught in school that New Haven was indeed the “Model City,” for all of America.

And yet in stark contrast to those hopes and promises, New Haven ended up being torn apart by racial strife and economic inequality. The political and economic decisions to build highways through the city were well-intentioned, but the results were grave. These dividing highways ended up ruining the educational system, tearing apart the social fabric of the city, and destroying the possibility of it being the great “City on a Hill.” The aspirations and disillusionment of living there were very formative for me. There was a shared and widespread sense of betrayal, of lost hopes.

So certainly growing up in New Haven heightened my awareness of what was wrong in the world.

Joel: Do you want to talk about Larry [Sultan]?

Jim: I don’t mind talking about Larry; he’s on my mind all the time.

Joel: Let me preface with the fact that I think this is a great document, The Last Son. I think in some ways, it’s your most emotionally compelling document because it has such a clear narrative and it’s so easy to identify with you that it takes the viewer along emotionally. But what also strikes me is that this is a book that’s going to have a place within photography with those books that explore personal history, parents, and family. And how striking that Pictures From Home by Larry is also a paradigm in that category — a great paradigm. I mean, sometimes, something is just in the air, people just happened to know each other in Paris in the 1920s. But it’s rather an extraordinary thing that you do this great personal narrative of family history and so does Larry. You were both so close.

Jim: Larry was my first real mentor who ultimately became my best friend and brother. So there’s no question about his influence on me.

Though our strategies were different, we were simpatico more often than not, especially with regard to how we wanted to use photography. We avoided didactic approaches and instead tried to use the medium as a way to question things, while riffing on the traditional documentary form. We constantly bounced ideas between us, which undoubtedly carries into both of our work.

I take to heart something that Larry spoke about often. That is, a “double vision”: although photographs are historical proof that something happened, the context of the images is two-fold. There is the time in which the picture was made, and the time in which it’s being viewed. Our perceptions change as time passes.

For example, Larry’s parents were younger in the photos he made of them for Pictures From Home than when the book was published. So those photographs were not an accurate record of his parents, even though we sort of suspend our awareness of this reality when we look at photographs. For better or worse, photography both suspends and collapses time.

And, I am older now than my parents were at the end of The Last Son, when they retired to Florida. So there’s this experience of me looking at them, and at myself, and seeing our lives related but independent, within and outside of time.

While I was making this book, and simultaneously shooting for the Yale commission, I was also working on a third project with Nazraeli Press called, Ruby Every Fall. In it I look at my daughter’s life and her first day of school every year through the end of college.

All at once, I was looking at pictures of Ruby getting older, seeing myself get older in her eyes, while also looking at my parents and their lives in The Last Son. I mention this because the serendipity of it all was so wonderfully pronounced. Of course it’s also frightening because it brings up my own mortality, but that’s another conversation altogether.

Joel: So what does it mean to you or to anyone to do a biographical work? I think that in some ways, all any of us are looking for is an intelligent witness to our lives. Does this book go in that direction for you?

Jim: Perhaps. My hope is that it brings to the present a trace of the past. And I hope that the story is told well, that it is elegant and honest.

I do admit that I have this unrealistic wish to get all of the ideas inside of me created, (including the sculptures,) so that I can see “how the story ends.” Maybe then everything will make sense, that I’ll get it all figured out.