Inside Saddam’s Iraq

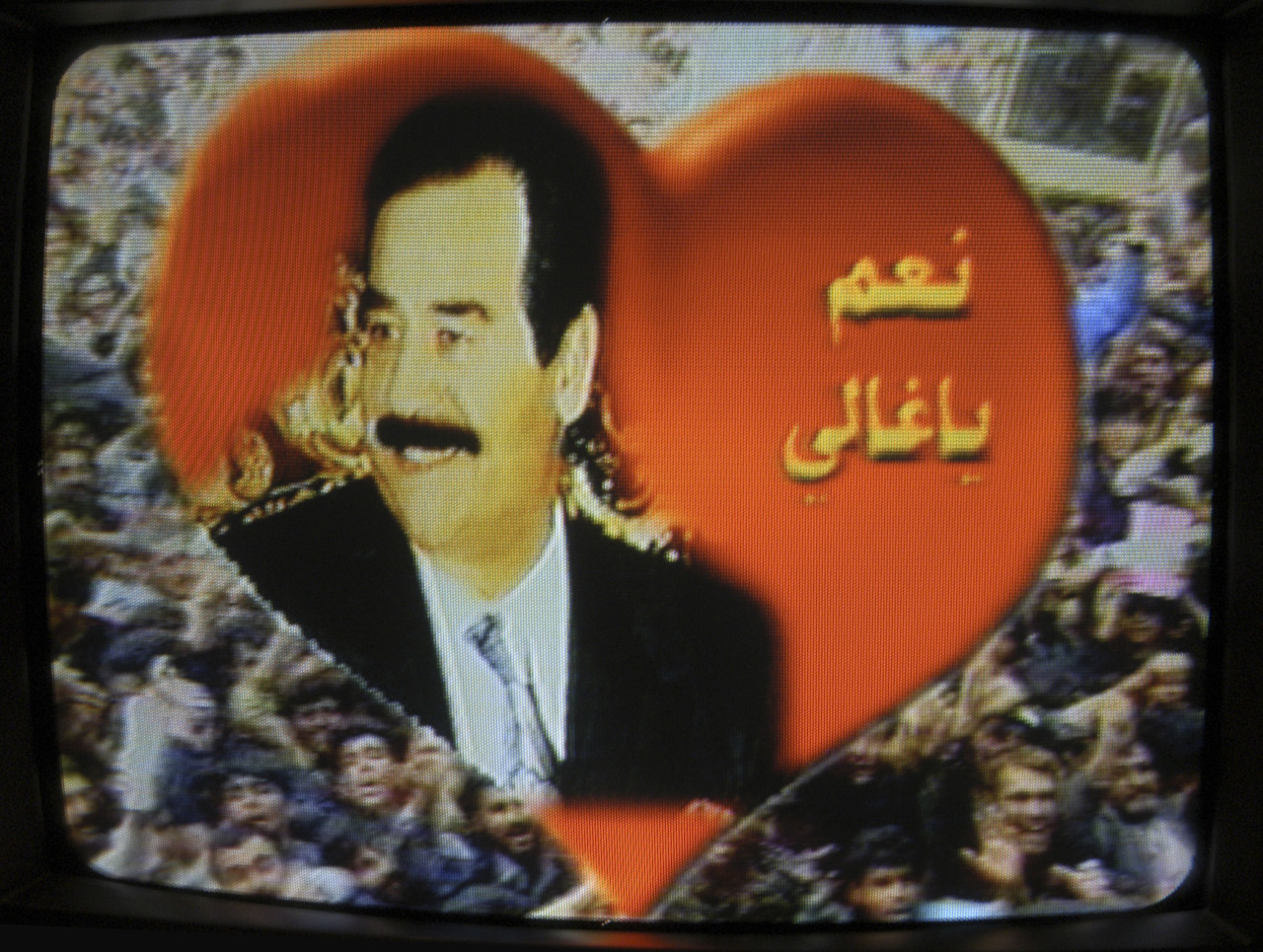

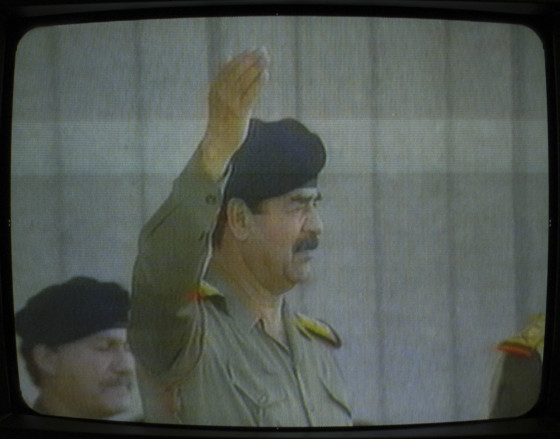

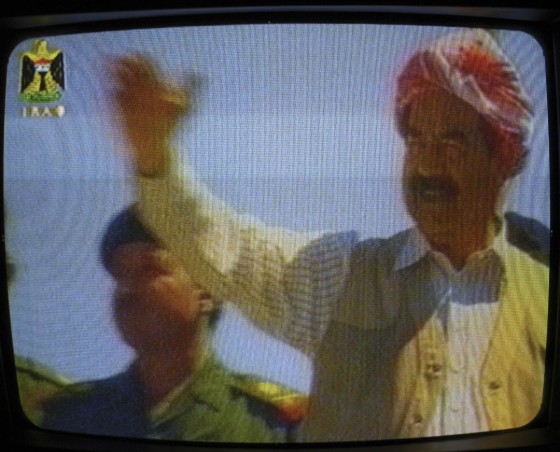

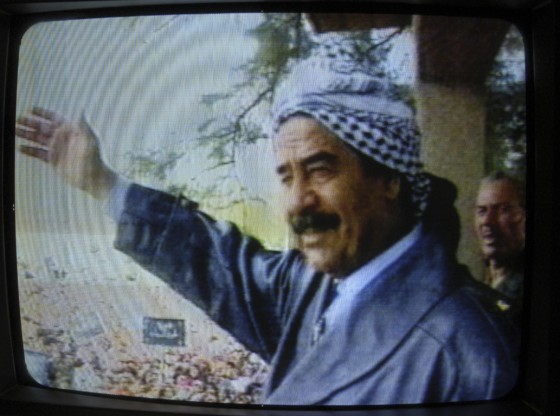

Fifteen years after the invasion of Iraq, Thomas Dworzak’s shots of Iraqi television propaganda in 2002 provide an unexpected glimpse into life in the police state

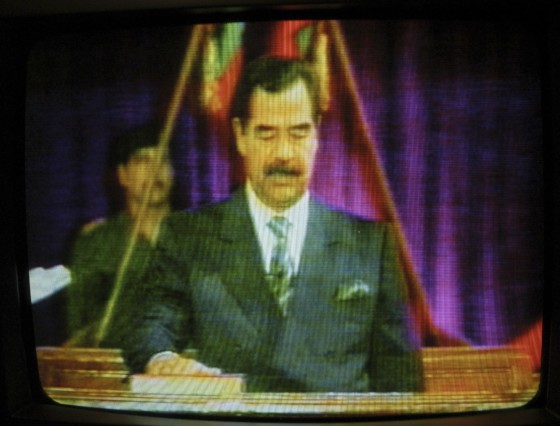

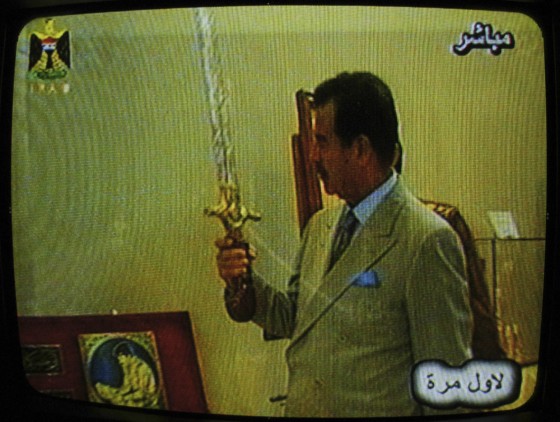

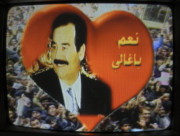

When Thomas Dworzak visited Iraq in 2002, he was told exactly what he could photograph. He wasn’t even allowed to take pictures from his window; all the doors in his hotel were plastered with signs warning him against it, entreating “No Photo on the Riverside” (eventually inspiring the series’ title: What They Are Watching – No Photo on the Riverside). And so, trapped in his room each day until his minder and fixer came, Dworzak photographed his television screen.

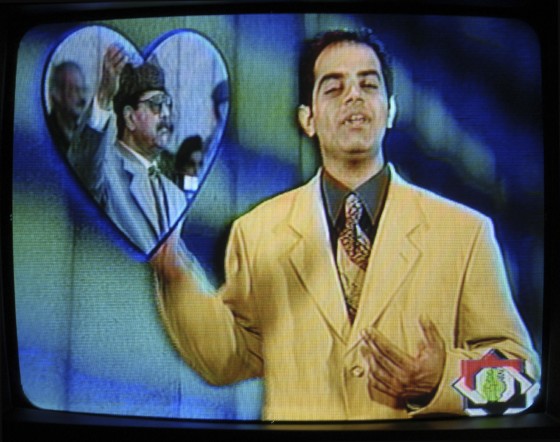

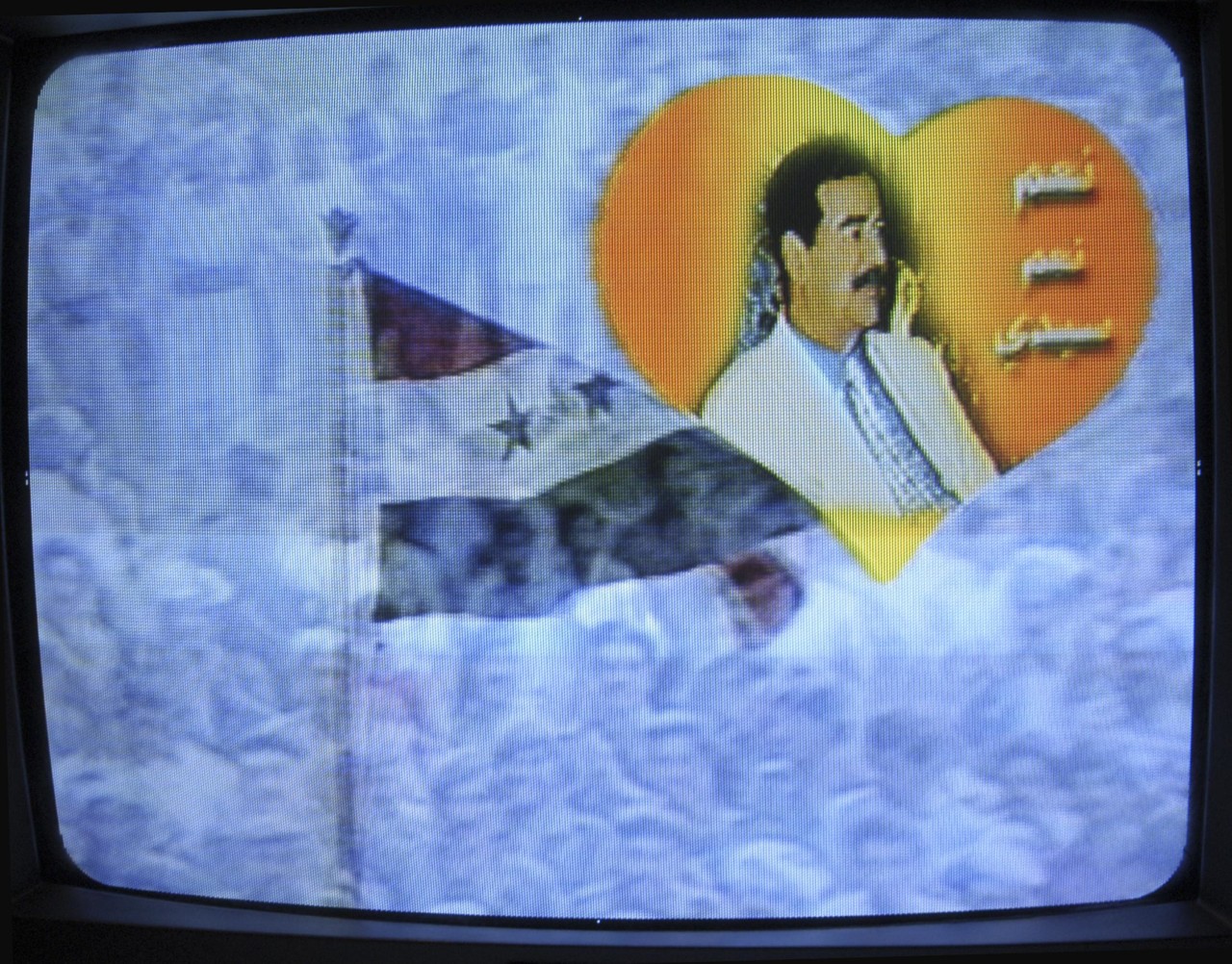

“It was probably more revealing than anything else they showed me,” he says. Back then, the three state-controlled Iraqi TV channels showed endless, looping footage of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein alongside military parades and a handful of musicians singing patriotic songs.

Hussein had risen to power in 1979 but toward the end of his rule, he hardly appeared in public, living in total isolation in one of the many palaces he had built after the 1991 Gulf War. According to reports, he was so worried that the US might identify his location via a phone call and use it to launch an attack that he only used a phone twice after 1990.

Though he grew increasingly reclusive, he nevertheless wanted to maintain his strong grip on the country. Iraqi’s state-run television was one way to reach and mobilize the Iraqi people. Prior to the April 2003 US invasion, Iraq had one of the world’s most restricted medias and Reporters Without Borders considered it one of the 10 countries most hostile to journalists and independent media. It called Saddam Hussein a “predator of press freedom.”

Saddam’s oldest son, Uday Hussein, ran Youth TV — the most popular of the three state-run stations. Only the country’s elite was able to afford satellite service, and even then it was restricted by the totalitarian Ba’ath regime. The Committee to Protect Journalists reported in its 2001 survey that “insulting the president or other government authorities is punishable by death. Hagiographic coverage of the country’s political leaders and vilifications of their enemies fill the press.” According to Reporters Without Borders, “journalists suffered all forms of brutal treatment at the hands of the Baathists and the media fell under severe censorship, restrictions, scrutiny, and persecution.”

Foreign journalists like Dworzak, who visited twice under Saddam, faced immense restrictions when covering Iraq, from government censorship to limits on visa stays. When Dworzak visited, it was ostensibly to cover the October 2002 referendum on whether Hussein should rule for another seven years. But Hussein was the only candidate; according to Iraqi officials, 100% of the more than 11 million eligible voters backed the president. As the US and UK ramped up demands for military action, voters were encouraged to show their support for the Iraqi leader at rallies, trampling American flags.

The Iraqi Ministry of Information’s provision of “minders” — the state-sanctioned individuals who shadow visiting journalists and arrange all interviews on their behalf — was another tactic to ensure journalists were forced to act as mouthpieces for state propaganda. “The whole idea behind this series was that either I could go out with my minder and take silly pictures,” says Dworzak, “or I could show this extreme version of what it was like to be locked in my hotel room until my minder came.”

Dworzak says there are about 157 scenes — “Saddam shooting with a hunting rifle; Saddam hugging his mother” — in total, and after about five minutes they would begin again. He says moving around in Saddam’s Iraq was a bizarre experience. “Everybody was so scared of Saddam; no one would speak. There was this alienation,” he says.

Dworzak was also there when Saddam Hussein granted amnesty to most Iraqi prisoners, virtually emptying the country’s jails in 2002. Before then, he says, you could hardly mention the name of the Abu Ghraib prison or even look in its direction, aware it was where the regime tortured countless prisoners. “It was total chaos. It felt real though,” he says.

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, more than 250 newspapers and magazines appeared — although they faced a variety of challenges. Fifteen years on, Dworzak’s photographs provide an unusual glimpse into Iraqi society during this period, a symptom of the decades of authoritative control and propaganda to which the Iraqi people were subjected.