The Legacy of the Iraq War: Two Photographic Perspectives

Moises Saman and Peter van Agtmael reflect on their work in Iraq for more than a decade

Magnum Photographers

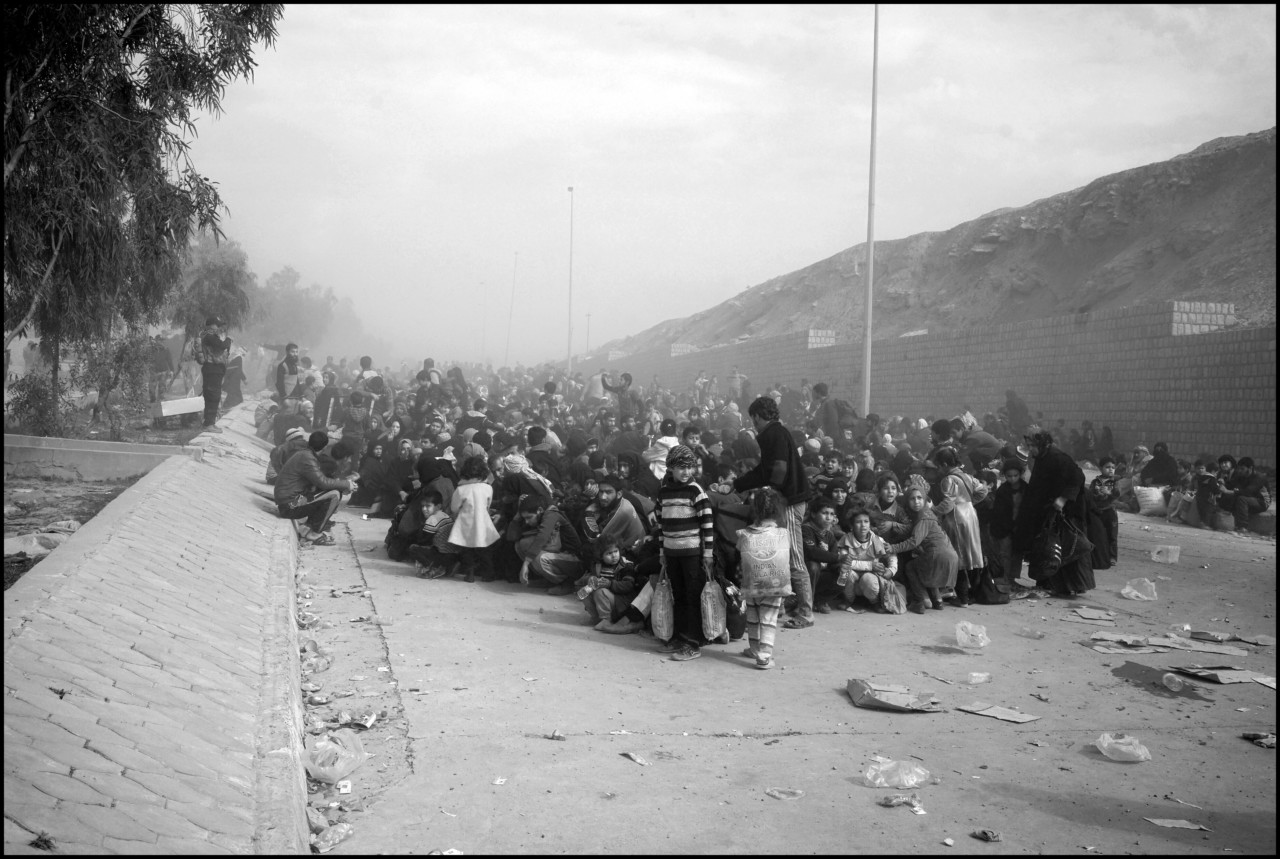

Fifteen years since the US led a military invasion of Iraq in March 2003, defying the UN and overthrowing the dictator Saddam Hussein, the country is still trying to rebuild and forge peace. Unlike many of the journalists who covered the initial invasion and the early years of the war, two Magnum photographers continue to return to Iraq. Moises Saman has spent 16 years working in Iraq, covering the invasion, the aftermath and the more recent war against ISIS. Peter van Agtmael has been working in Iraq since 2006, working initially with American soldiers and exploring the consequences of the war back home, and then since 2014, working more on the civilian population in Iraq and in exile.

We spoke to both photographers about the influence of the Iraq War on their photographic practices and how the country has shaped their careers — and personal lives.

Why do you think you keep returning to Iraq?

Saman: What started as assignments is now something very different. It’s not like I chose to go; it’s almost the opposite. As photographers, it was something inevitable. There was a bigger force behind making those decisions.

It’s a place that — sometimes by choice, sometimes by circumstance — I have found myself year after year. It also became personal. My wife is Iraqi-Kurdish, and that also opened up a completely new set of questions for me, a fascination about wanting to know about where she came from.

Now, it’s been close to 16 years and so I’m thinking about putting it in a book form because I haven’t really found an answer yet to some of my questions. It’s why I keep going back.

Van Agtmael: I’m interested in America and its shadow on the world since 9/11. It’s a history-defining event. My work in Afghanistan or on the Syrian diaspora or on refugees in Europe is all intertwined in some way with the conflict in Iraq and what happened in the wake of it. There’s no real end in sight — 12 years into my coverage of it; 15 years into this war.

There’s an arc but we don’t know where we are in that arc and we have very little idea of what’s next. It’s very long and well beyond my own lifetime. All I can do is commit to what I can do in my life — throughout my life I would hope.

How has your perspective on Iraq changed over time?

Saman: Going back again and again, you gain a little more perspective, you grow as a person and your sensitivities also grow.

It takes a long time to move away from the very immediate challenges, from covering the news, the daily grind. Now, I’m really not in a rush and want to do it right — to look at the bigger picture, to tackle questions that are more thematic than the historical perspective or battle tactics of the war in Iraq. The nature of war, the ambiguity, the victim/perpetrator dynamic — these are the dialogues I want to have about war and conflict. For me, returning to Iraq and now having also a personal stake in the fact that part of my family is from that part of the world, I really feel this need to say something perhaps more profound.

Van Agtmael: When I went to Iraq, I was 24 and I hadn’t been a photographer very long. I was suddenly in the midst of a very serious war that was extremely banal at the same time. It was easy to see it as an American war at that stage and that age.

As I started working outside the military framework, in the Middle East generally and in Iraq, starting in 2010, I started getting a dramatically different picture of the people and the culture. I started making friends there and fell in love with the culture in many ways.

It was a remarkable society with admirable qualities, and you could see almost no trace of that from the embed. This lack of imagination about the true Iraq was a testament to just how dysfunctional this occupation was. The disdain, ignorance and arrogance of many American soldiers was staggering. But I only realized this when I myself was able to step away from the context of the embed. So I get it, and in many ways am incriminated by it.

"It was a remarkable society with admirable qualities, and you could see almost no trace of that from the embed. This lack of imagination about the true Iraq was a testament to just how dysfunctional this occupation was."

- Peter van Agtmael

How did Iraq influence your other work?

Van Agtmael: I ended up photographing people back home that I’d met in Iraq or Afghanistan, or people connected to them. It seemed important to bridge these areas and home. Many of the soldiers’ families and friends had trouble relating to what went on and were more impressed by the spectacle. I thought it maybe had a lot to do with how far away it felt and so I wanted to create this familiarity and framework; the pictures could reinforce one another in more powerful ways.

I’d grown up in a bubble in the northeast. Where I was from, not many people went into the military. I started to follow stories about soldiers at home in America, going to states I’ve never been to. Slowly, I started to build out my own idea of America. I was surprised by how little I understood about my own country. A lot of Americans found out how little they knew about America when Donald Trump got elected. It’s important to be ever mindful of these forces below the surface. There is no substitute for experience, and even thoughtful media creates a wildly disjointed perception of reality.

How does working in Iraq today differ from during the war?

Saman: Right now, it’s safer than let’s say two years ago, but not as safe as six years ago. That translates in terms of having to adapt to different security arrangements. I think my appearance also helps — I can sort of blend in quite easily in the Middle East. Perhaps for someone Caucasian, the threat of kidnapping would be too much.

Van Agtmael: The conventional wisdom is that at this moment in war coverage, there’s a lot less freedom of movement; that journalists are not seen as neutral but as tools to be leveraged. I don’t know if that’s actually true. There’s certainly been an uptick in the killing and kidnappings of journalists. But when I started covering Iraq in 2006, there was a huge kidnapping risk. The war was really turning from something where photographers and journalists could work relatively unimpeded without a lot of advance planning to only being able to work embedded. And so from my frame of reference, photography has always been in the time when it was dangerous to be a journalist. When I was in Mosul last year, it was possible to work relatively freely but there were a tremendous number of risks. Kidnapping, snipers, car bombs, conventional weapons, chemical attacks…

"Now I like working in a way that asks more questions than giving answers. "

- Moises Saman

How did Iraq affect you personally?

Saman: It wasn’t good for personal relationships; it was only good for your own career. No one knew the war was going to drag on so long. If anything you embrace that downward spiral — or at least I did, and I know for a fact many other people did. The war became your life; the intensity of it really took over everything else.

Van Agtmael: Everyone has their own trajectory. For a time, it was pretty much a singular obsession that did start to take its toll. There’s a real, dark danger in being obsessed with covering war all the time. At some point I became mindful that it was taking a toll on my emotional health but also atrophying other parts of myself that were not being developed because I was so focused on myself. A combination of factors — a catastrophically failed relationship and a near-death experience — made me rethink my choices.

Saman: You surround yourself with similar kind of people and engaging with people outside of that circle became more and more difficult. It was important for me to learn how to get out of that circle, to grow as a person and as a photographer.

Van Agtmael: I knew Iraq was important to me and I had more to say. I just became more mindful of having balance. The impossible question is “when do you say it’s time to stop and move on? I do think about how I’m going to sustain this until I’m an old man: emotionally, physically, photographically, intellectually, artistically. In terms of energy as well. If any one of these things wanes too much, it’s hard to sustain.

How does your earlier work in Iraq sit with your approach today?

Van Agtmael: Photography is good at showing the human terms. When I was working primarily with the American soldiers, I was trying to tell a complex portrait of America at war — but it was nevertheless within the conventions of photographing an army at war. When it came to turning my lens onto the Iraqis, Syrians or Afghans, it was a much richer, nuanced portrait of a whole society — emotionally and photographically. It was important for my own reasons of identity to explore the American perspective but once I saw what I was missing, it dramatically changed my focus.

Saman: Back then I was more focused on getting that one picture that tells the story. Now I like working in a way that asks more questions than giving answers.

There are moments now that are perhaps more meaningful than I could see back then. The editing process, that’s where I find the language and the narrative; it’s where you can really shape things. When I have time to look at the work I was shooting then, these sensitivities I have now will hopefully allow me to see things I didn’t see then.