The Troubles: Capturing the Conflict

Twenty years on from the historic signing of the Good Friday Agreement, Magnum photographers reflect on their coverage of the Northern Ireland conflict

Magnum Photographers

Borders, literal and figurative, have long been a prominent part of Northern Ireland’s landscape. And with a border comes two sides, necessarily and historically opposed.

The thirty-year civil war – a chaotic period known as “The Troubles” – officially began in 1968 but the bubbling violence which marked it was laden with deep-rooted divisions. Indeed, the conflict could be said to have begun 800 years prior, when the Normans first invaded Ireland and heralded centuries of direct English rule. Social and economic inequalities, religious difference and the erosion of cultural expression were all woven into the complex fabric of war and the scale of suffering was both epic and individual. By the mid-1990s, more than 3500 people had been killed.

The historic signing of the Good Friday Agreement on April 10, 1998, officially brought an end to the sectarian conflict and peace for many. But, as John McCallister, former Ulster Unionist Party deputy leader, told Politico: “We have been stuck for 20 years with ‘all my side were heroes, all your side were terrorists.’ We are not going to agree the narrative, so why pretend we can?” The impossibility – and futility – of an agreed perspective is prescient when considering how the conflict was documented. Is it ever achievable to accurately capture both sides of war?

Twenty years on from the Good Friday Agreement, Magnum photographers who covered the conflict reflect on this question and how it played out as they witnessed it. For Abbas, the war was more tribal than it was religious. Ian Berry saw violence so profound that for the second time in his career he considered putting his camera down and intervening. Poverty formed the backdrop of Chris Steele-Perkins’ work, while Philip Jones Griffiths was drawn to the effects of colonisation, as they had already played out in his home-country of Wales.

Today, as Brexit looms larger and the divisions that have haunted Northern Ireland threaten to crack wider and deeper once again, these photographs speak to the futility of borders that separate people who are fundamentally the same.

Philip Jones Griffiths – as told by Katherine Holden, daughter of the late photographer

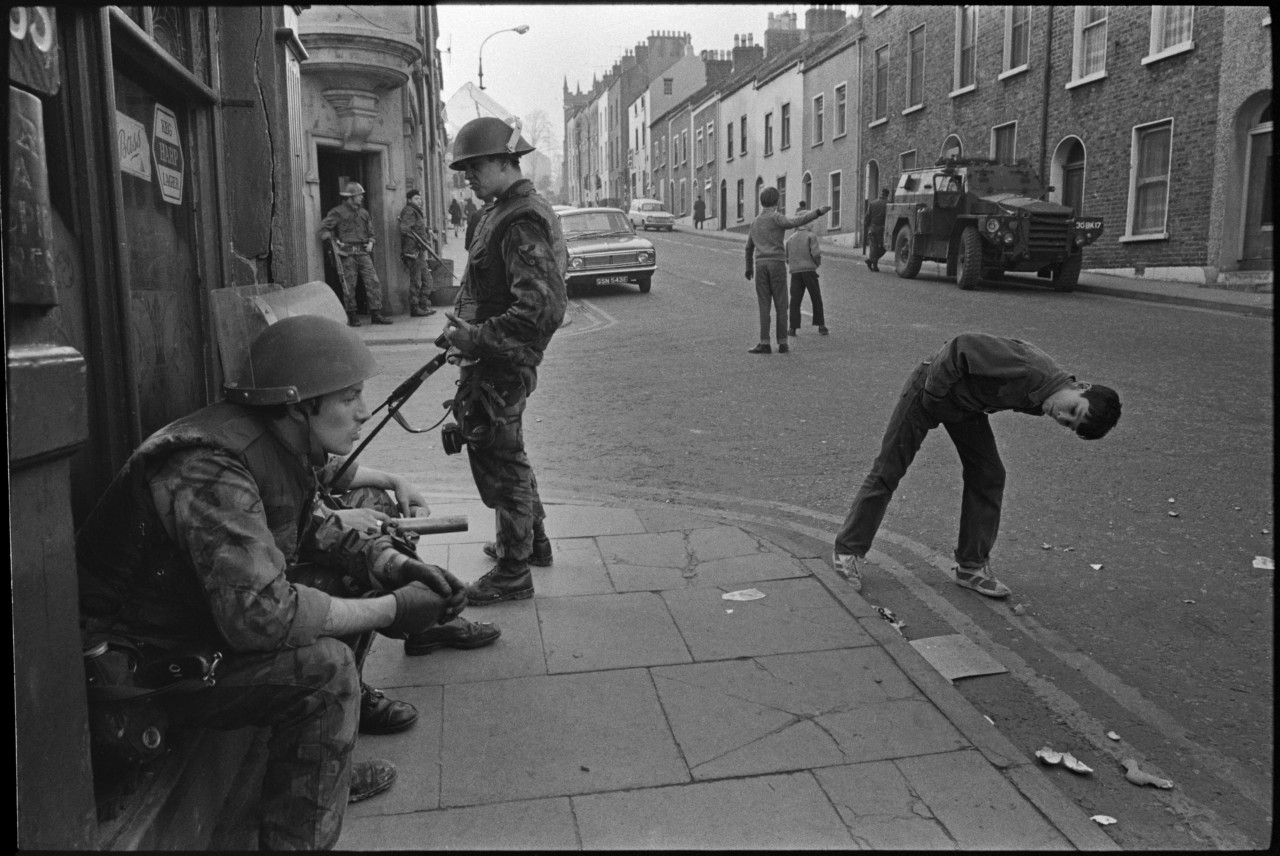

Philip grew up in North Wales in the shadows of English castles. He knew what it was like to be the under-dog and was instinctively able to recognise the imperialist yoke around the neck of a society. This theme was developing in Philip’s work, drawing him to document scenarios where imperialist forces impose their military might onto people’s front doorsteps.

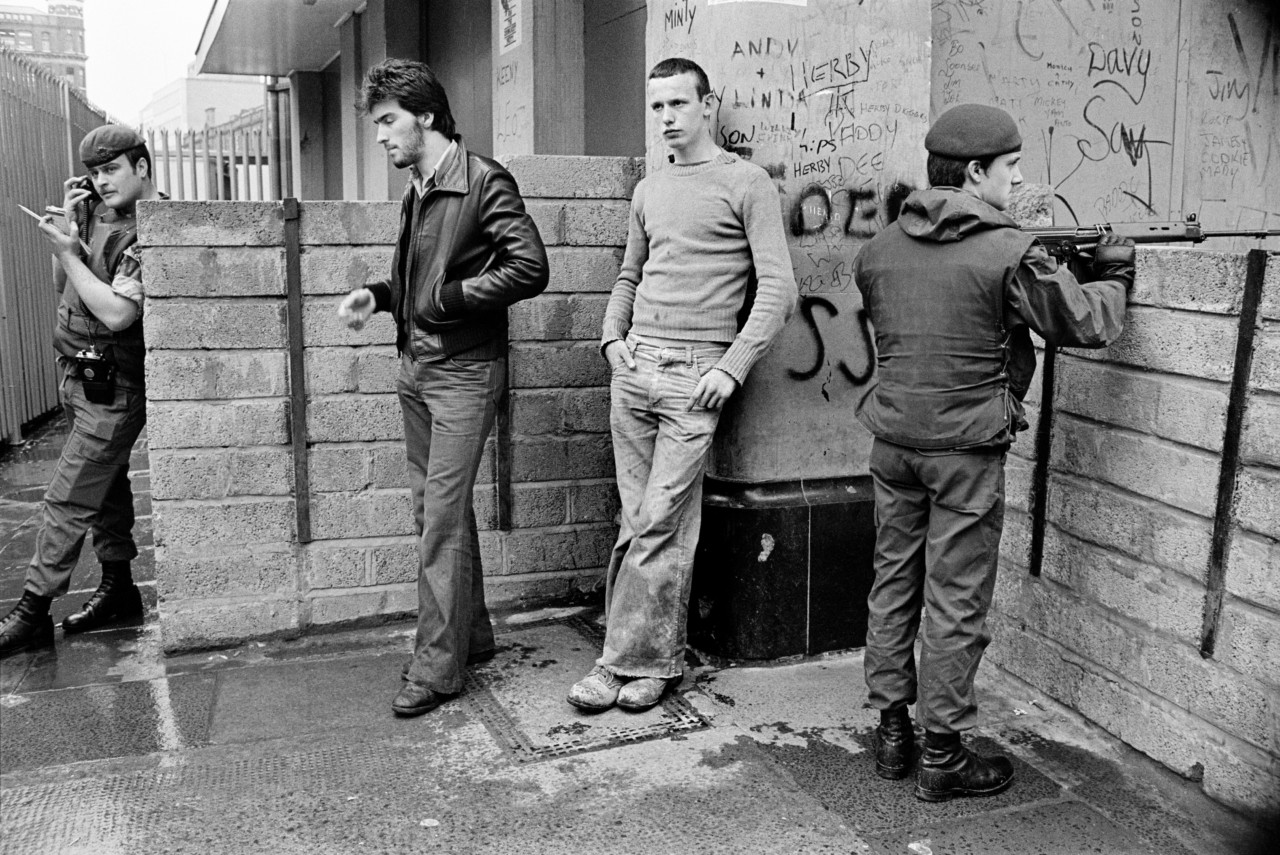

Philip once said: “The conflict in Northern Ireland has provided a revealing study of the way the British State deals with an urban uprising. It is an unsavoury little war that seems to have more to do with providing basic training in counterinsurgency techniques for the British Army than keeping the peace.”

He started documenting The Troubles from the mid-Sixties and while the reasons behind the conflict are extremely complex, bringing in questions of territory and religion, what was also being fought over was two different versions of a national identity. Ultimately, as with so many imperialist ventures, it comes down to the ‘hearts and minds’ of the people.

I think it was probably quite difficult for Philip to take on a completely objective view of this conflict. I don’t think he was there to give balanced coverage. I think his goal was much more to show and document the reality of daily life; to shed light on the actual people living in and with conflict. I think that’s one of the things that makes the picture of the soldier through his riot shield so powerful. There’s a person behind there, not a mechanised tool of war. Both sides, only really separated by ideas and scratched perspex.

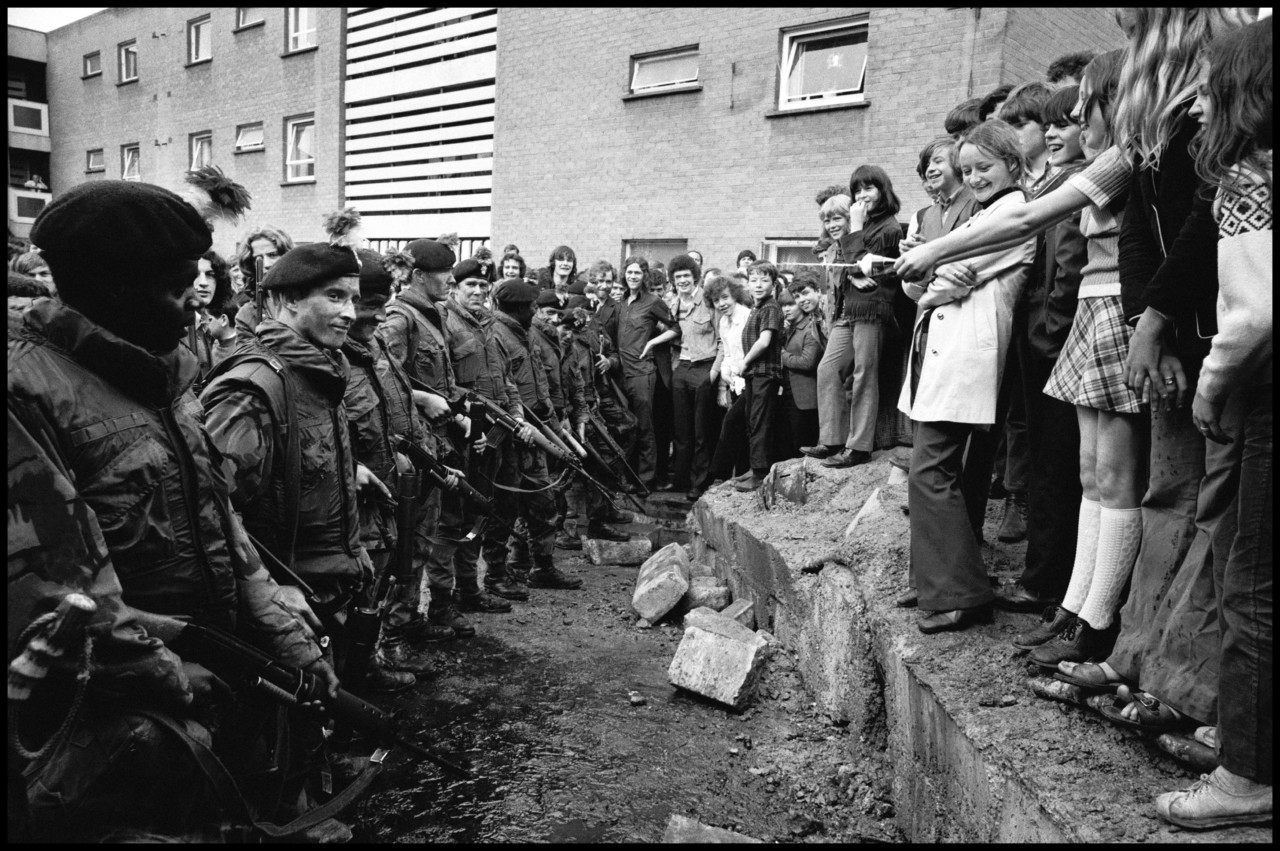

As well as this focus on the humanity in these types of situations, Philip also had a sharp sense of humour. I’m not sure you could ever describe his practice as being ‘light’, but he often used a dark sense of humour in his work. The scene of a soldier lying behind sandbags as people consider buying pork chops from the supermarket, or the woman mowing her lawn whilst a soldier crouches in her bushes are so dark and abstract that they almost become comical. He also deeply appreciated ‘cheekiness’. The kid playing with a soldier, or the teenagers spraying the soldiers; these are all examples of the kind of heartwarming resistance that I think Philip admired.

I think his images in Northern Ireland serve as a reminder of how quickly normal people can find themselves living in a war zone and subject to military might. They speak to the importance of diplomacy over violence. They show how oppression begets oppression. How violence begets violence. In terms of Brexit, I personally think they show the difficulty that comes with the concept of borders, literal divisions between people who are essentially the same. If you have a border, there will always be two sides.

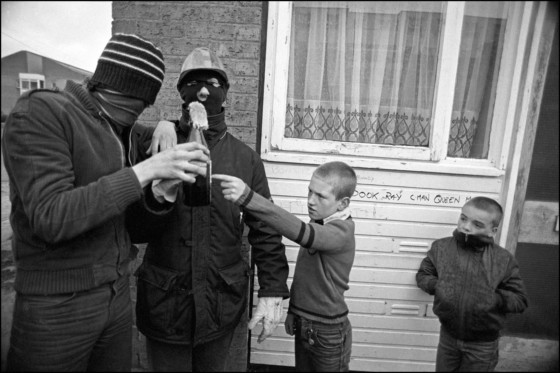

Chris Steele-Perkins

My work on Northern Ireland was part of a larger project called Survival Programmes that I was making with two other photographers, Nicholas Battye and Paul Trevor, documenting poverty in Britain’s inner cities. I was keen to go to Northern Ireland to put the conflict into a context of the poverty. Because poverty seemed to be one of the driving factors of the whole Northern Ireland conflict – more so than religion, in my view.

It seemed self-evident that the Protestants had a case that was unsustainable. It was a bit like apartheid in South Africa – it just didn’t make sense and it couldn’t go on like it was going on. Some of the atrocities that the IRA and splinter groups pulled off were awful of course but overall I certainly felt like I was on the Republican side.

I wanted people to feel that I was sympathetic to them rather than standing at a distance. I was invited to stay with a couple of guys who had a squat in the Divis flats and it was there I met the President of the Housing Association, who invited me to stay with him and his family. He was a well-known figure in West Belfast – no deep political connections – but a respected figure in the community and that helped a huge amount.

I was met with an extraordinary sense of welcome because I think people felt I was trying to do something about their condition rather than simply reporting on a problem, which is what most people were doing. I didn’t have any deadlines; I didn’t have to produce a picture a day for a newspaper. So I could just dig around and photograph what I found interesting – to try and get behind the news in a sense.

When I’ve covered conflict in places like Lebanon or El Salvador or Afghanistan I’ve always been interested in looking at the community and the environment from which this is all taking place. I was always concerned about not just painting the most dramatic picture that I possibly could because it wasn’t honest. I tried to put the violence into a social, political and cultural context.

I photographed community festivals in the area and things like that, which were always ignored by the mainstream press because they didn’t fit the narrative of violence, hatred, bigotry, which was there but it was there coloured by some great community work, moments of gentleness, normal family life and really decent people trying to get by – and I think it’s a shame to ignore that.

Abbas

In the 70s I was covering all kinds of wars, civil strife and revolutions so it was natural for me to go to Northern Ireland – there was something important going on so I went there.

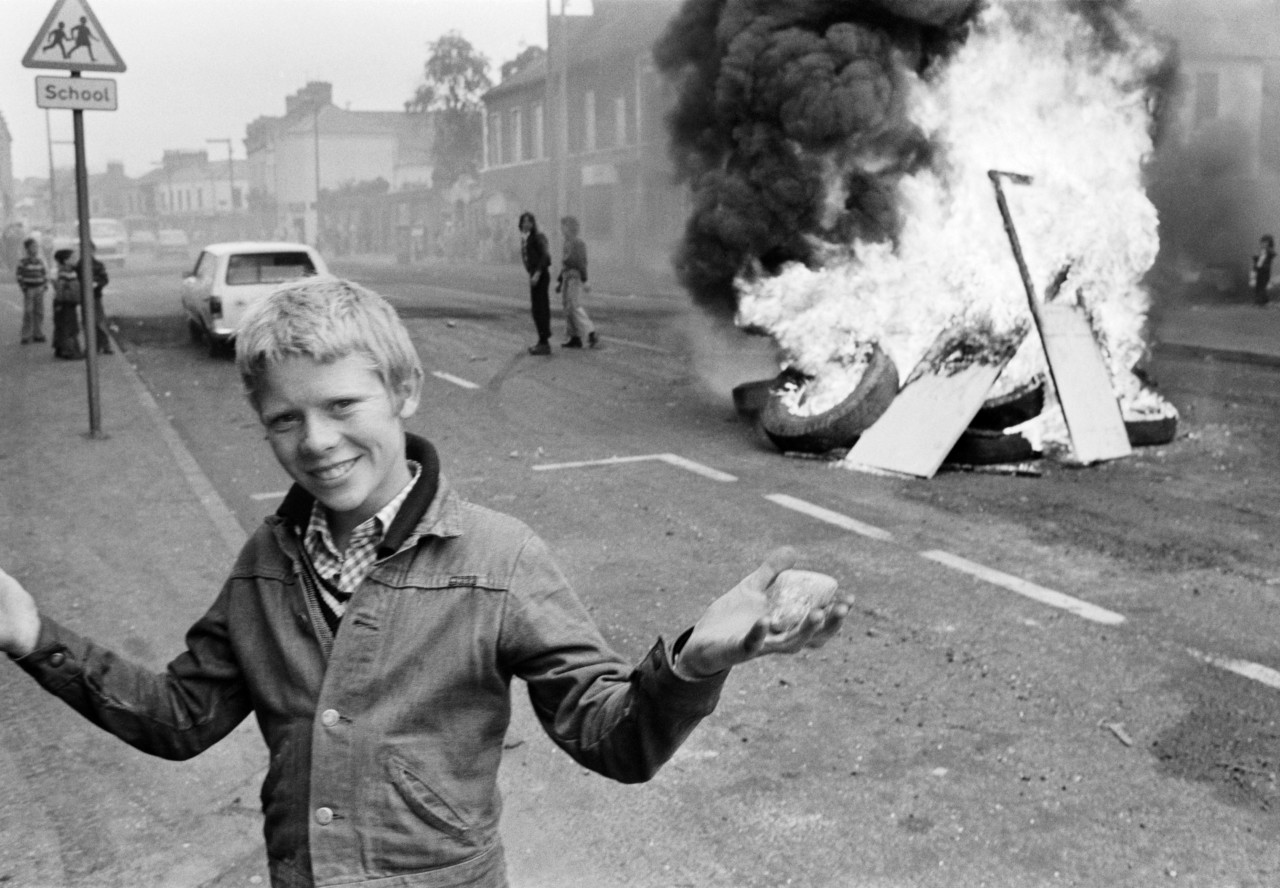

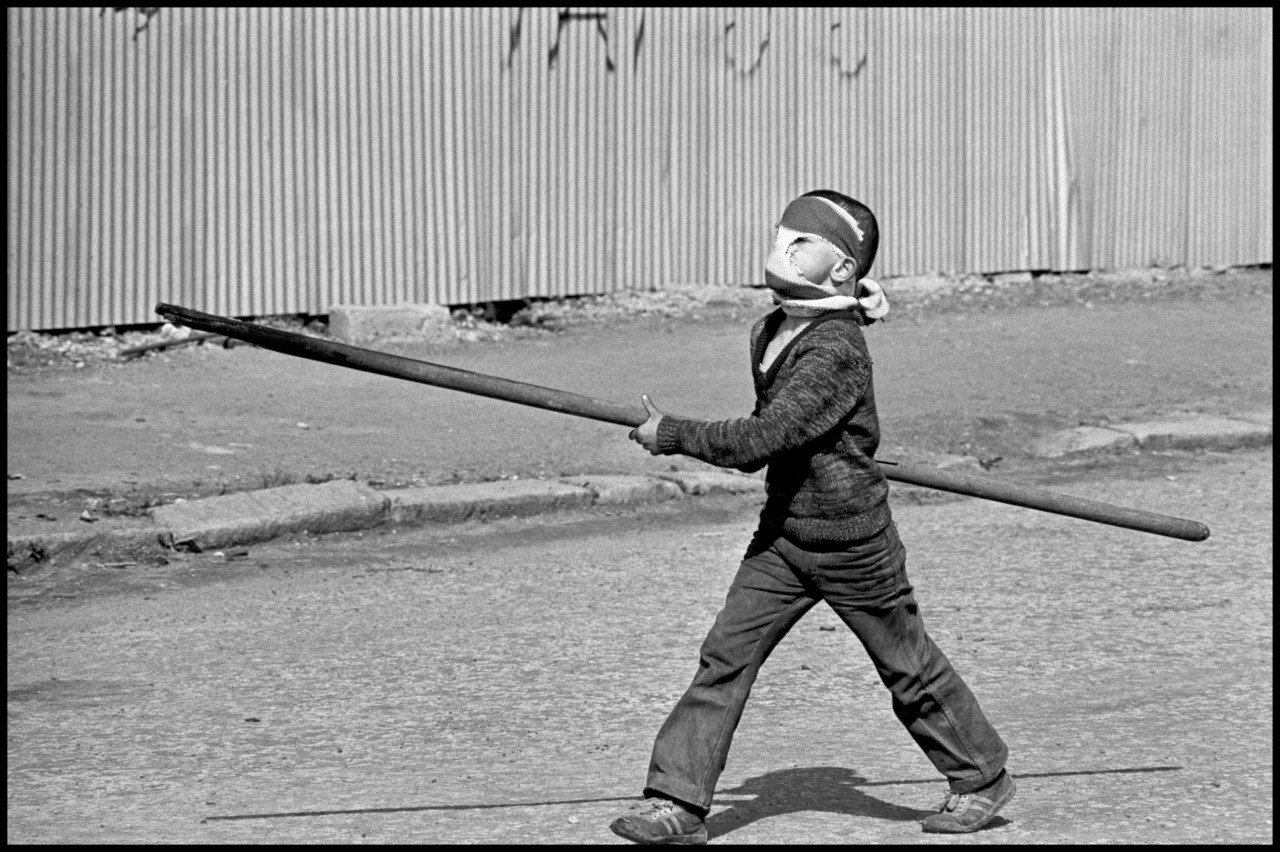

I remember the first day I arrived in Derry, I met a bunch of kids who said: “You want to see us throw stones on the soldiers?” And I said: “No I don’t want to.” They said: “Come on, come with us, we’re gonna throw stones”. Of course there is this element of people acting up for the photographers – and not just in this civil war. You have to have enough experience not to play into their hands. And even when they’re acting for you, you might get a picture that doesn’t say exactly what they want to say.

A lot of the conflict was happening in the streets but if you wanted to give the broader background to what was happening, you needed to cover all sorts. I covered some Orange meetings, I tried to cover the culture around the events… That’s what I always tried to do. As a photographer, when you cover a civil war or a war, it’s not just about the battle and the violence: wars are very complex phenomenons which have aspects that are social, economical, psychological, and in this case, religious, as well. So you have to put what you’re seeing – events unfolding – into perspective.

It is always important to me to present a balanced perspective of conflict. I might have my own thoughts or passions but I hope not to let them influence my photography. I’m not an objective photographer, I’m very subjective because when you decide to photograph this frame instead of that one, you’re making a choice or a judgement and therefore you’re subjective. But I try to be fair and that means I tried to cover both sides of the conflict. In fact in 1972, I tried very hard to cover the IRA. I worked always on the Protestant side but I met contacts and I went to the pubs where the militants would meet… I would try very hard but they just wouldn’t have it. They weren’t hostile, they just said no. Maybe they were afraid I was an informer; they had reasons to be suspicious.

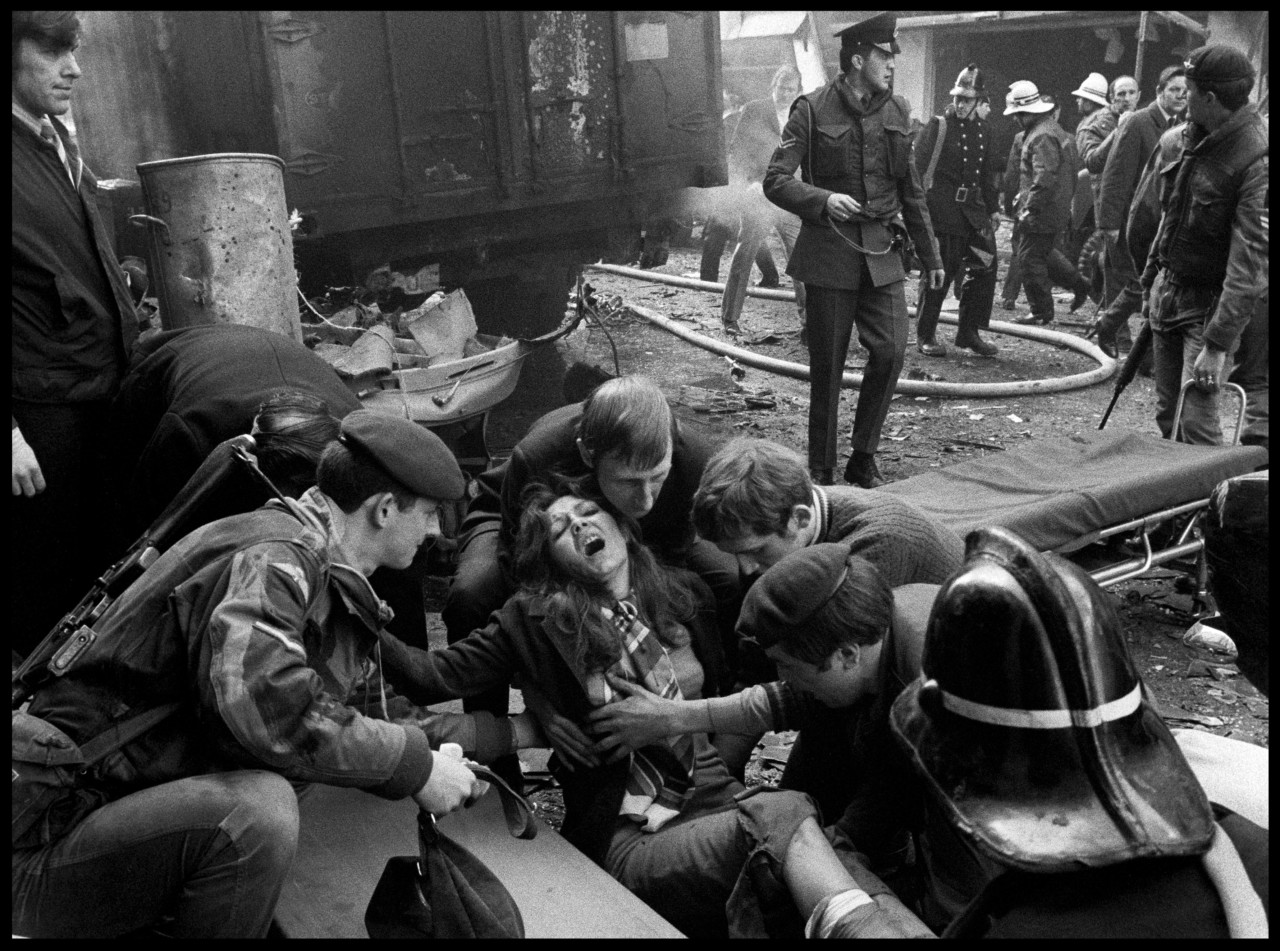

There are two pictures that I am really fond of; the picture of the wall crumbling and the picture of the woman wounded from the bomb explosion. They are action pictures and they reveal what goes on in a civil war: the destruction, the wounded, the suffering. The wounded woman was an innocent civilian who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. It moved me; but when you’re photographing you don’t allow yourself to be moved, you just function very fast because events develop very fast. Even if I’m faced with people suffering, I never put my camera down because I’m a photographer; my function is as a photographer.

When I went back to Northern Ireland in 1997, I realised what the conflict was about. It wasn’t really a civil war, it was a remnant of the colonisation of Ireland by the British. I don’t think it was a struggle or a fight between two religions at all, it just happened that the people who didn’t want independence were Protestant and the people who did were Catholic. The war was more tribal than it was religious. Very often you wonder why they’re fighting because culturally they’re the same people. Religion was important but it was secondary to the tribal aspects of the civil war.

Ian Berry

The British army had initially been welcomed by both Catholic and Protestant sections of the Northern Irish community. But then there was a story in the Sunday Times that the army were losing favor… so I thought it would be worth going to see what was going on.

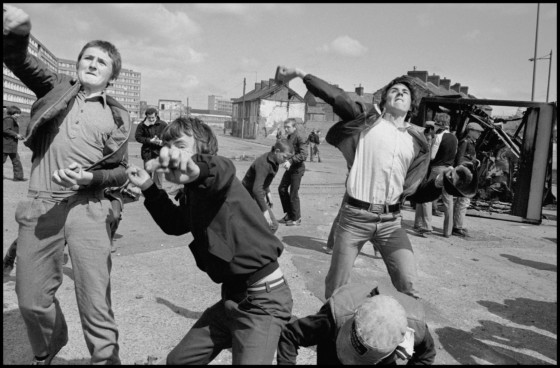

I started to follow a section of British soldiers and saw how they would get into a position where some of them would stay behind a wall and some of them would tempt in the gang leaders. The kids would follow them through and the soldiers behind the wall would grab them. I took photographs of them beating the hell out of these kids; they were kicking them and bashing them with their rifle buts. I got a bit nervous; it was the second time in my career when I thought: Do you stop being a photographer and start to interfere? I was at that point, when luckily for me a British officer turned up, saw what was happening and stopped them. He made the decision for me, which is a good thing because I still don’t know what I would have done.

I always try and play an even hand. As well as the soldiers, I went on and joined the guys throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails. They were children who were readily arming themselves. The bigger kids would tend to wear masks so that they wouldn’t be recognised but the smaller kids didn’t really care because they couldn’t be charged anyway. What I found was that the best way was to get very close in with wide angles when they were throwing rocks because then they throw them over your head not at you. The closer you are to them the better but the only problem then is you’re not watching your back for the rubber bullets coming in.

I realised I got some rather good pictures of both sides so I nipped back to London and went with an agent to the Sunday Mirror with the processed prints. But they were too nervous to take them; they didn’t want to show the British army in a bad light. The Express said the same. I returned to Northern Ireland and got a call from my agent to say the Correspondent newspaper would take them. Of course the Correspondent published all the pictures of the kids throwing Molotov cocktails and none of the pictures of the Army beating up the kids. But even though all the pictures weren’t used in England, they were used in Germany and France – everybody else who didn’t mind showing the British army in a bad light.

I covered Bobby Sands’ funeral in 1981 but for me it was somewhat devoid of emotion. It was a bit like the funerals in South Africa where it was taken over by a political party. It was somewhat taken over by the IRA. Which is why I think my favourite picture from that is the one of small boys joshing each other in front of the coffins painted on the road; that summed things up more for me rather than the pictures of the funeral itself. Because having photographed all these kids preparing Molotov cocktails and so on, that picture told me that at the end of the day, kids will be kids. Even if they’re part of this big political scene, they are still kids. God knows how it influenced them all in later life but at that moment they seemed to be out of the whole funeral. For me that was more symbolic.

That conflict has been going on in Ireland forever, it wasn’t exactly a new situation. And if they try and stuff in a new border between Northern and Southern Ireland now, you wonder will it all start up again? Because it’s all simmering under the surface. You walk around Belfast today and there is still that wall. Okay, it’s covered in graffiti but it’s still there – separating the Catholic and Protestants.