Broken Manual: Alec Soth in Conversation with Aaron Schuman

The Magnum photographer talks about the personal impetus for making Broken Manual, the desire to be an artist, and the frustrations of photography

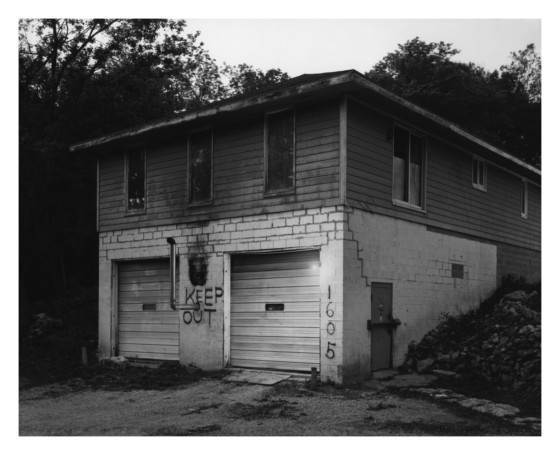

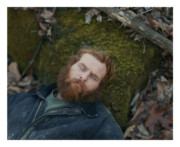

In 2010, Alec Soth released Broken Manual, a publication that explores the desire to disappear, the people who crave an escape from both their lives and civilization itself – such as monks, survivalists, hermits, runaways, and more – and the places where they seek refuge. Modelled on various self-published pamphlets and underground instruction manuals that Soth encountered during his research at the time, the book represented a significant departure from the more conventional documentary approach of Soth’s early career (such as in Sleeping by the Mississippi and Niagara), and incorporated both autobiographical and fictional elements, as well as drawings, quizzical images, and the writings of “Lester B. Morrison” – a pseudonym that Soth assumed for the purposes of playing the character of a recluse himself within his own story.

Alongside its publication, Broken Manual also took exhibition form, first appearing at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 2010; since then it has served as one of the chapters in Soth’s survey project, Gathered Leaves, which has been touring internationally since 2015. Currently, selections from Broken Manual are featured in the exhibition Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins, which is on display at the Barbican Art Gallery in London until the 27th May 2018.

(The following conversation was conducted via Skype, on 20th March 2018)

Aaron Schuman: Hi Alec. Thanks for finding some time to talk about Broken Manual.

Alec Soth: Sure. What kind of structure are you in? It looks like a barn or something?

Schuman: I’m in my attic, where my office is – away from the rest of the house and the family. Where are you?

Soth: I’m just in my studio. Strangely, this particular room directly relates to Broken Manual. I originally had only one space as my studio, but then this space became available. There used to be a florist in here – when she left, I was afraid that some auto-mechanic or something would move in, and actually the controls for heating and ventilation system in this room are in my studio, so I decided to get it. This all happened around the same time that I was working on Broken Manual, so I painted this room grey – the same grey as I paint the gallery-walls when I exhibit Broken Manual – and in my studio it’s always referred to as “The Cave”. Today, it’s just the name we use for this room – it doesn’t really have that same meaning to me anymore – but it’s still my place away from the rest of the studio.

Schuman: What do you do in “The Cave”?

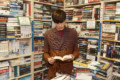

Soth: There’s the library. I also have my treadmill desk in here at the moment, and all the current “Seesaw” stuff, just because I don’t know where else to put it. I guess it’s just a place to think.

Schuman: Could you explain what got you into that particular headspace around the time of Broken Manual, in which you felt like you had to find a “cave”?

Soth: Like I said, I’m in a very different headspace now. But at that time, I’d just done Niagara, and I felt like I was finally “established” or whatever. And for some reason, when I crossed that threshold, I became frustrated with the medium of photography – I didn’t want to repeat myself, and I didn’t want to give in to marketplace pressures. Maybe pretentiously, in retrospect, I was thinking along the lines of, “I don’t want to be a photographer; I want to be an artist”. It was partly that, and also maybe domestic life was wrapped into it too – kids reach a certain age, everything becomes a little chaotic, and I was a bit like, “Get me out of here!” I always joke that Broken Manual was my “midlife crisis” project.

"I don't want to be a photographer; I want to be an artist"

- Alec Soth

Schuman: In Broken Manual, you – well, “Lester B. Morrison” – writes quite a bit about mid-life crises.

Soth: Yeah, it was that time in my life. It’s funny – now I’m sort of embarrassed about it. I look back and see a white guy whining about his art-world success. Given the current moment, it’s kind of like, “Maybe that’s not so cool.”

Schuman: A lot of the project is about the contrast between the romantic or idealistic dream of escaping, and the rather sad and potentially pitiful nature of that kind of reality.

Soth: That’s true; it’s self-mocking in a way. In the photographs, I don’t think I’m mocking the people that I encountered, but in the texts I’m definitely mocking myself. The inspiration for the “manual” aspect of the project came from buying all these “How to Disappear” books online – they’re so absurd. They’re such ridiculous little pamphlets, which would be completely ineffective if you really wanted to run away. So there is a real dark-comedy aspect to the work.

Schuman: How did you go about gaining access to all of these people who wanted to completely disappear – what happens when you turn up at their hideout or property with a camera?

Soth: It’s funny, because I created the whole fictional structure, the “manual” format, “Lester B. Morrison”, and so on in order to place the project within this other realm; it’s not meant to be a documentary project about people that are running away. I was photographing people who were semi-recluses, but that said, they’re not real recluses – they were more apart from society than other people, but they still functioned in society. For example, some of the monasteries I visited actually had visitor centers. When I went to Gethsemani Monastery in Kentucky, where Thomas Merton has been a monk, I was really surprised to find that one of the monks was a keen photographer. He was so excited when he saw me with my camera, and offered to show me the cabin where Thomas Merton used to meditate. It seemed so contrary to the idea of retreat and meditation.

Schuman: Who is “Lester B. Morrison” to you now, in retrospect?

Soth: Now, he is a fully fictional character. Originally, I was really set on the idea of doing the whole of Broken Manual under a pseudonym, but then I lost control of it. In a sense, I was promoting myself through a fake identity, but at the same time I was angry at myself for being so self-promotional. I wanted to obliterate myself, but I also want to publicise my obliteration. Lester B. Morrison is really wrapped up in that. The name came about around the same time that I started Little Brown Mushroom too. I was trying to develop this secret, private language – the way people who’d spent too much time with themselves do, or people who exist in very tight communities, like gamers or whatever; a coded language. Somewhere I’d stumbled across that term “little brown mushroom”, which mushroom-hunters use to describe an unidentifiable mushroom that is very common. I really liked that, so I came up with the pseudonym “LBM”. Then “Lester B. Morrison” came out of the idea of “less is more”, “less be more”, and he just became this character. Originally, I was going to do all of the Broken Manual work in his name, but then it became impossible, so he turned into someone that I’d met whilst travelling and photographing these other people. He took on another life.

"I was trying to develop this secret, private language – the way people who'd spent too much time with themselves do"

- Alec Soth

Schuman: In your interviews and the conversations with “Lester”, published in Broken Manual, he really lays into you – frequently berating and criticising you.

Soth: Well honestly, that “midlife crisis” thing I mentioned earlier wasn’t such a joke – I really was having a midlife crisis. I would actually come to this room – “The Cave” – get really drunk, and work on these things. I’d write, and do drawings, and so on. But a lot of that stuff is a blur to me, and it’s kind of embarrassing now. Part of the idea was that it was intended to not be very good; I wasn’t aiming to write a piece of literature. It was meant to be kind of shitty – that’s also the way the book functions in terms of being printed on 8.5×11-inch standard office paper. So getting drunk, holing up in “The Cave”, and working on this thing was also, in some ways, in the spirit of the project. But I don’t even remember a lot of it – not so long ago, I looked back at the book, and I was like, “Wow, I did an interview with myself?!”

Schuman: In that interview, “Lester” makes fun of you for wanting to be “recognised and celebrated”, whereas he just wants to “invisible and alone”. I guess that’s what was going on in your head as well – you were having this kind of battle with yourself, in your own mind.

Soth: Yes, I always have that battle going on – I think about this a lot. Even yesterday, I posted a picture of my eyeballs on Instagram, but I’ve always had this thing about not showing my eyes on Instagram. Ever since the beginning of Instagram, I’ve badly wanted to photograph myself like everyone does and show selfies; I want people to like me. But I’m disgusted by that urge, so I always want to scratch out the eyes – but I still want you to like me. It’s this constant back and forth, wrestling with the desire to be liked, and my frustration with that desire.

"There is a real dark-comedy aspect to the work. "

- Alec Soth

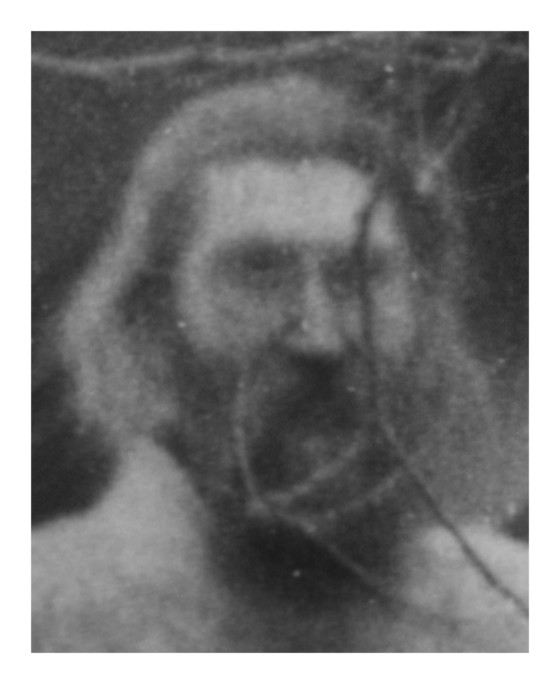

Schuman: Included in the ephemera that comes with Broken Manual, there’s a print where you’ve digitally obliterated your face – there’s also a found family photo, where the face of the husband/father is violently scratched out.

Soth: Actually, that family photo has an interesting backstory. When I was photographing Niagara, I met a woman, and she showed me this picture with her husband. Then – right in front of me – she scratched his face out. It was such an aggressive gesture. I asked her if I could keep the photograph, and she said, “Sure”, and handed it to me. And of course, wrapped into Broken Manual was the theme of domestic removal and men leaving their family behind, and for me that picture was super-charged with the experience of watching her scratch out that man’s face.

Schuman: Broken Manual is also partly about the dangers of spending too much time alone. But in many ways being alone – on the road, in hotel rooms, on planes and so on – is the nature of your life as a photographer.

Soth: Absolutely. The reason I wanted to become a photographer was to spend time alone. It’s funny, because for the last year and a half I’ve been trying to learn how to work alone again. The psychological elements of working alone are so profound.

"A lot of the project is about the contrast between the romantic or idealistic dream of escaping"

- Aaron Schuman

Schuman: What are the benefits of being alone?

Soth: For me, being alone is really connected to travel. The benefits are that there’s no escape – you have to work, because what else are you going to do; how are you going to justify this behavior. I think the little tinge of madness that comes from spending too much time alone can be a good thing – you can access something real. But there many dangers as well, like being super-navel-gazing or pretentious.

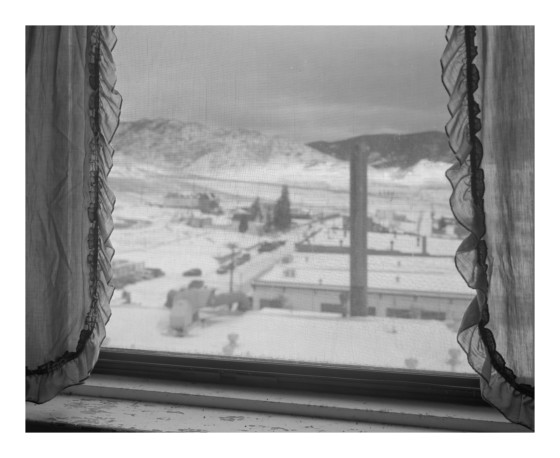

Schuman: I wanted to ask you about a few specific pictures in the book, Firstly, there’s a photograph called “Frank’s View”, which directly references and recreates a Robert Frank photo that he made in a hotel room in Butte, Montana, which was first published in The Americans. How does this particular photograph fit into the scheme of Broken Manual?

Soth: The book includes quite a few inside jokes with myself. By calling it “Frank’s View”, it makes “Frank” sounds like the first name of a person to me – maybe people get it, or maybe not. But in terms of the scheme of Broken Manual, I thought about Robert Frank being alone, travelling, making pictures. So just out of curiosity, I went to Butte, which is the most amazing town; Wim Wenders has photographed there a lot – it’s like candy for a photographer, because it once was a boomtown, so everything is bigger than it should be. There’s this giant hotel with however many stories, but today they only keep the first two stories open, so the room where Frank stayed is now closed; you have to ask to go up there, and I’m not even sure I was in the exact same room as where Robert Frank was. I’m not uptight about that stuff. But what I love about his photograph in The Americans is that it’s as much about Frank as it is about Butte. It’s looking outside and inside at the same time; it’s using the outside world to speak about an internal experience – it’s autobiographical in nature.

In terms of the American road-trip photography tradition, I originally fell in love with Joel Sternfeld and Stephen Shore’s work, but not so much with Robert Frank’s. But later on, what I realised is that I’m actually much closer to Frank in spirit than I am with Sternfeld or Shore. Sternfeld is very sociological. Shore is very observational and all about seeing. But Frank can be super navel-gazing. I always think about Frank – transitioning from The Americans to his Nova Scotia work, and how it reflects his frustration with his success. Going to Nova Scotia was sort of his retreat, and the work he made there was sometimes amazingly great, and sometimes was incredibly self-indulgent. I feel like I’ve been walking that same line. I’ve always said to the people who work in my studio, “If I ever start painting on my pictures, hit me with a two-by-four.” But suddenly, with Broken Manual, I was kind of doing just that.

Schuman: Are there any pictures in Broken Manual that were truly “fictional”, in terms of being entirely constructed or staged?

Soth: That’s a good question, but weirdly, no – that said, there are more inside-joke pictures. There’s a picture of a boat, which is the first picture I ever made with an 8×10. And there’s a picture of Charles – the guy who’s holding the airplanes in my most famous photograph from Sleeping by the Mississippi; in Broken Manual he’s one of the zoomed-in blurry ones. I play these little games with myself throughout the book.

Schuman: It also seems like Broken Manual represented an opportunity for you to break away from your past, and the way you traditionally made photographs. Of course, it still contains many large-format portraits and landscapes, but then there are also all of the blurry images, the studio still-lifes, the texts, the drawings, and so on. In a sense, you were pushing past your self-imposed boundaries, and trying to find something beyond what you were known for.

Soth: That’s true, but I think that by continuing to use the 8×10 it shows that I was also still struggling with the idea of breaking away from it all. For instance, all of the blurry, far away pictures were made on an 8×10, with very expensive color film. Why would I do that, knowing that I would eventually scan the negative, make it black-and-white, and only blow up a little detail? I could have just taken a snapshot with a point-and-shoot, but somehow it felt important to me to still use large-format at the time, even with these little pictures.

"I play these little games with myself throughout the book."

- Alec Soth

Schuman: At one point in the texts, “Lester B. Morrison” mentions J.D. Salinger in the context of famous recluses. I know that you have a habit of tracking down and trying to photograph some of your heroes – for example William Eggleston, who appears in Sleeping by the Mississippi. Did you ever try to find and photograph J.D. Salinger?

Soth: No, not Salinger, but I did track down the writer and poet, Wendell Berry, while I was making Broken Manual, which led one of my most humiliating moments ever. I don’t know if you know Wendell Berry, but he’s kind of the Robert Adams of writers – he’s very pure. So when I was travelling through Kentucky, I ended up talking to these local farmers in a diner, and found out where Berry lived. I went to his house, but down by a nearby river there was this tiny cabin with smoke coming out of the chimney. I wondered if it was connected to him as well, so I went up and knocked on the door. He opened the door, and was so pissed off – I mean really, really, really angry. I drove away and parked by the side of the road, thinking about it, because I was embarrassed. And then a few minutes later, he and someone else drove by and saw me parked there – I guess I was still on their property – and they started yelling at me, “Get out of here!” It was a horrible feeling.

Schuman: That was probably his little writing retreat – his “cave”.

Soth: It totally was! And I really wanted to photograph it. But of course I didn’t. Exactly – it was his cave.

Schuman: That’s the kind of reaction I would have imagined you would have gotten from nearly every one of your subjects in Broken Manual.

Soth: It’s true, but most people are actually very welcoming. But they’re not famous people. Wendell Berry genuinely has a huge following, and I imagine that his little cabin really is a legit escape for him from all of those people. I’m not one of his “disciples” or anything, like I would be with Robert Adams. I would never in a million years go to up to Astoria, Oregon and stalk Adams. I did it with Eggleston a long time ago, but I was more stupid then, and the circumstances were very different.

Schuman: You’ve recently released a new edition of Sleeping by the Mississippi – are there any plans to do the same with Broken Manual?

Soth: There’s no plan. I kind of like that there are only a few copies them out there – the book, and its relative scarcity, have now become a part of the project.

Schuman: You said that when you look back at Broken Manual now, you’re a little bit embarrassed?

Soth: Yes, a little bit. I mean, I like it – but yes, it’s a little embarrassing.

Schuman: What role does it play in your work and in your thinking today? Did it act as a kind of exorcism, whereby you needed to get all of this out of your system, and then you could be free to go back to working like you used to; or did it genuinely change you in a profound way?

Soth: I often think about my work as sitting on this spectrum between inward-looking and outward-looking. I see Broken Manual – and that way of working – as sitting near one end of that spectrum. But I’ve gone much farther than Broken Manual on the inward-side of that spectrum; I’ve gone way too far before. And then, I’ve also gone the other way. For me, it’s always about going back and forth between these two ends, because I crave change and need to recalibrate myself sometimes. That’s why I’m not dismissive of Broken Manual; I do like it, and I think it has a place. Just this morning, I saw a post online in which Wes Anderson was talking about how he always had his own stylistic approach, which he called his “handwriting”; at a certain point, he just accepted his “handwriting”. I feel like this narcissistic side of things is at least a part of my “handwriting”, and I have to accept that a certain amount of it is going to be in my work. Sometimes I’m embarrassed by it, or I want to be more of a “pure” photographer or something, but maybe I just have to acknowledge and accept it. I’m always wavering back and forth between these two poles.

Schuman: Do you imagine that you’ll ever veer so close the inward-looking side of that “spectrum” again in the future?

Soth: You know it’s funny – after Songbook, I bought this abandoned farmhouse about an hour and twenty minutes away from my studio. Originally, it was a big secret – I didn’t tell anyone, and no one had been there; my wife hadn’t been there, the people who work in my studio hadn’t been there – and I was making work out there by myself.

"I often think about my work as sitting on this spectrum between inward-looking and outward-looking."

- Alec Soth

Schuman: Did anyone know that it existed? You must have at least told your wife about it.

Soth: She knew that it existed, but I didn’t want to share it – it was clearly functioning in that ”cave” sort of way. And I’m sure that, as a consequence, the work that I made out there was really, really bad.

Schuman: Can you talk me through one example?

Soth: Oh, God. Alright – let’s just say that smoke machines were involved.

Schuman: That’s enough. That’s all I need to know.

Soth: Also, the house kept getting broken into – all the smoke machines got stolen, for example, as well as my metal detector and other things. These break-ins really bothered me, because I had a lot of crazy shit in there as well, so it made me feel very vulnerable. So eventually, I stopped making that work, and then I had my big spiritual encounter and decided to start –

Schuman: Wait, what was the big spiritual encounter?

Soth: I mean I had, you know, a “spiritual awakening”, as you might call it. I was in Helsinki, I was doing a lot of meditating, and I just had this “Oh my god, everything is connected” kind of experience. So that happened, and I decided to change things about my life – now I’m vegetarian, I stopped drinking, and really I was planning on quitting that farmhouse work for sure. But then I decided that maybe I could go back to the farmhouse without all this fear, invite people to come with me, and just have experiences together. So I did that for a year, and was very happy – just making sculptures, videos, audio recordings, and that sort of stuff. But now I’ve left that work behind, which is a more complicated story. I mean, I really like the work that I made, but I don’t think that it’s for other people.

"Broken Manual is also partly about the dangers of spending too much time alone"

- Alec Soth

Schuman: So it’s only for you?

Soth: I think so, or at least the audience that would get it and enjoy it would be incredibly minuscule. I don’t really want to ask a gallery to show work that I know only a few people would be interested in, or subject myself to not having an audience. I’ve always believed in using art for communication’s sake, and in the case of the farmhouse work, I was using it more to communicate with myself and experiment with my own practice. It is what it is, and now I’ve moved on from that.

Schuman: Is it very important to you that you have a substantial audience, and that they “get” your work?

Soth: When I’m making work, I always think about an audience – which isn’t saying I don’t want to challenge them, but I also want to let them in. This is something I think about a lot. I don’t want to be totally blank or ambiguous.

Schuman: Do you find that Broken Manual has a particularly specific or slightly more limited audience, as opposed to Sleeping by the Mississippi, Songbook or whatever?

Soth: Oh yes. Once, there was even a guy who had a Broken Manual tattoo. I can totally see how it might speak to a certain kind of angsty person, and funnily it seems speak to younger people in particular, for whatever reason.

"In America, there’s this kind of obsession with the black-hatted cowboy – the misfit, the recluse, the outlaw. "

- Alec Soth

Schuman: Throughout Broken Manual, you make it very clear that, in a dark-humor or tongue-in-cheek way, the book – or at least the premise of the book as a “manual for disappearing” – is targeted specifically at men (presumably middle-aged white men). What kinds of responses have you had from members of your audience who are women?

Soth: Yeah, sometimes women have responded negatively to it. I’ve never had a woman say to me, “I really love Broken Manual!” – both Niagara and Sleeping by the Mississippi get more affection in that respect. I’ve also been challenged, with people saying, “Don’t you think women have this feeling too, of wanting to disappear?” And I say, “Absolutely, I totally get that.” But really, the book is a fictional account, it’s about myself in some ways, and is about that specific culture or tradition of the American white guy wanting to get away from it all. In America, there’s this kind of obsession with the black-hatted cowboy – the misfit, the recluse, the outlaw. We’re having pipe-bombings in Austin right now, and it’s like you can almost play the movie in your mind of who the bomber is. I was driving my daughter to school today, and we were listening to the news about these pipe-bombings. She’s always had this interest in FBI profilers and that kind of stuff, so I starting making up my own profile of him – “White, male, thirty to forty, dark hair”.” She said, “Why dark hair?” And I was like, “I don’t know – it’s just a feeling.”