Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s Documentation of South Africa’s Drug Epidemic and the Aftermath of Violence

The 2018 Magnum nominee discusses his route into photography, the impact of South Africa's history of violence on his practice, and his ongoing personal projects

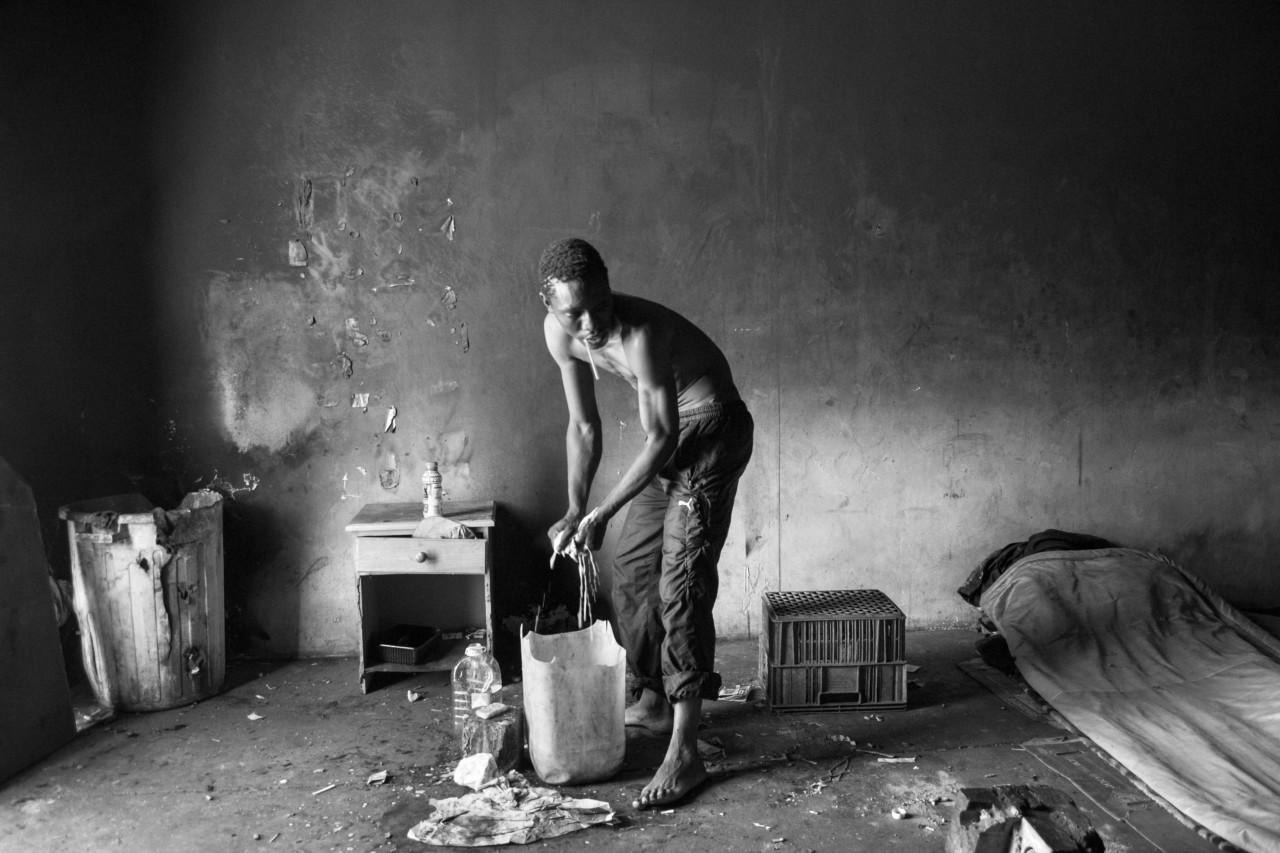

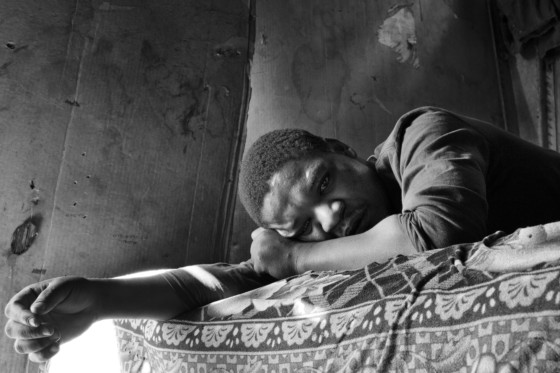

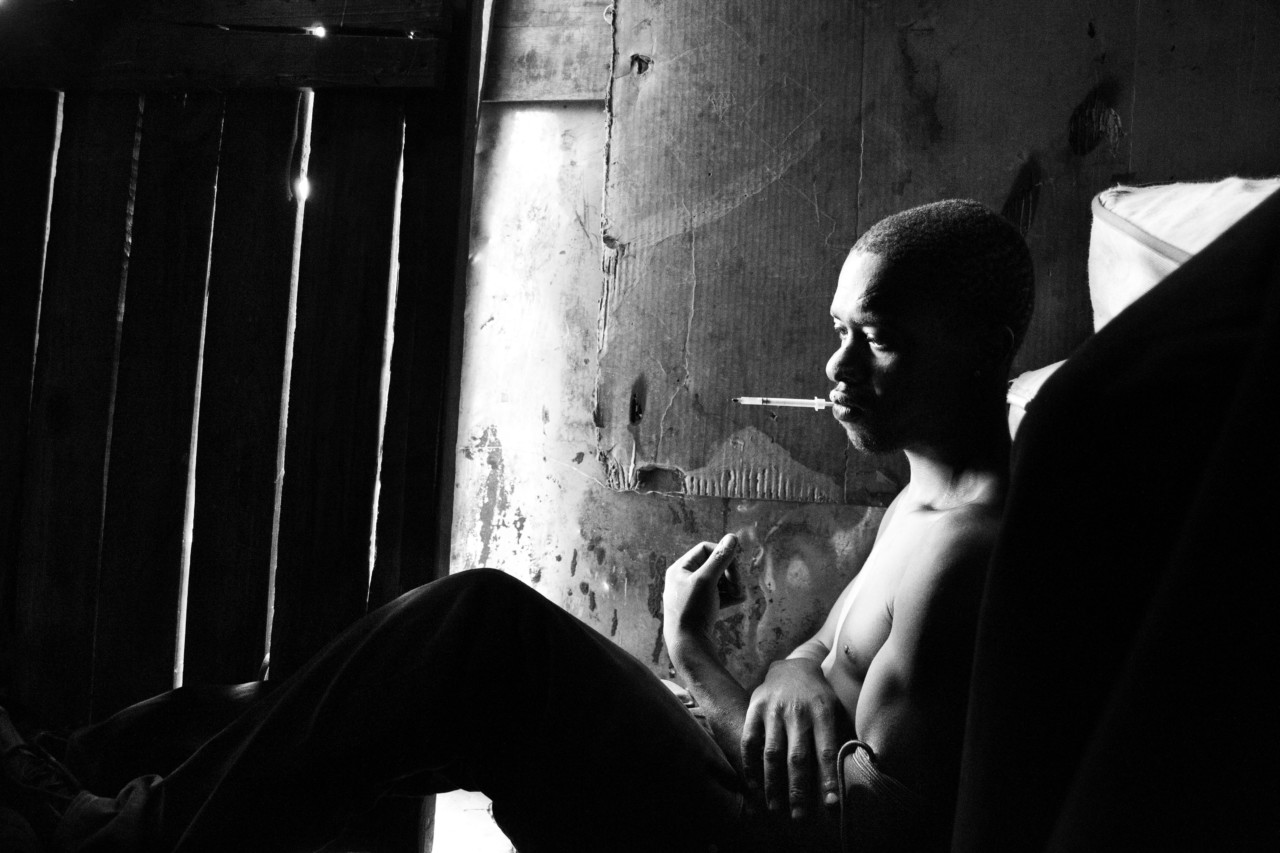

2018 Magnum nominee Lindokuhle Sobekwa was born in Katlehong, Johannesburg in 1995. Sobekwa came to photography in 2012 through his participation in the Of Soul and Joy Project, an educational program run in Thokoza township. The townships of his youth informed his earliest photographic work, a project on childhood peers and friends who had fallen into a cycle of drug abuse, specifically using the heroin-based nyaope which has become a widespread public health scourge in South Africa. After working with Magnum photographers Bieke Depoorter and Mikhael Subotsky, Sobekwa’s work on the drug was published in South Africa, and internationally in 2014. Here, Sobekwa discusses his influences, practice, and ongoing projects, including his deeply personal work on his sister, who died after becoming estranged from her family.

Having recently become a Magnum nominee, can you explain a little about how you came into photography, and subsequently the agency?

It started back in 2012, when I was doing grade 10 in Buhlebuzile Secondary School. My art teacher asked me to become part of the series of photography workshops that was introduced by the Of Soul and Joy Project, a long-term art initiative undertaken in 2012 by Rubis Mécénat Cultural Fund at my high school. It was my first time holding a camera, it made me cool, people started inviting me to their wedding functions, birthday parties – from then onward I always carried my camera with me. This was my way of making pocket money. Money that I could spoil myself with – I could afford soccer boots and a pair of sneakers.

My interest in photography grew as I progressed with the classes and I realized that photography wasn’t all about taking pictures at weddings or graduation ceremonies. It was also a way to tell my own stories, stories that concern me and the people I live with.

One of my first teachers of photography, and also my mentor, was Bieke Depoorter. She introduced us to photographers, and photographic books, many by Magnum photographers. At the awards ceremony at school I was awarded a book: Magnum Revolution: 65 Years of Fighting for Freedom. What I liked about it was the diverse voices and experiences, and a variety of young and old photographers. This book showed me different ways one could take pictures and the storytelling that came with photography. Then I started looking up Magnum on the internet and became really interested in the agency. When I was in New York on a Magnum Foundation Photography and Social Justice Fellowship, in 2017, I met some Magnum photographers – this was a great experience for me. I thought to myself: I want to become part of this agency. My time frame for that was maybe ten years, little did I know it would be much sooner.

"I realized that photography wasn't all about taking pictures at weddings or graduation ceremonies. It was also a way to tell my own stories"

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

I had a long, insightful conversation with Bieke and my other mentor – Mikhael Subotzky – about me and applying to join Magnum. I honestly did not think it was possible, looking at how young I am. Even though deep down I knew I was ready, I wanted to save myself from the misery of not being voted in. To cut the story short, I ended up applying, and today I’m a 2018 Magnum nominee.

Aside from those you already mentioned, in the early days of your entry to photography, which other photographers were particularly inspirational to you?

I was particularly interested in the works of Ernest Cole, specifically House of Bondage; in Santu Mofokeng’s series Chasing Shadows; in David Goldblatt, especially the series Some Afrikaners; in Thabiso Sekgala’s Homeland; in Madoda Mkhobeni’s Trolley Pullers; in Andrew Tshabangu’s Water is Life. I drew inspiration from Mikhael Subotzky’s series Beaufort West and Bieke Depoorter’s series Ou Menya. And my friend Tshepiso Mazibuko’s series Gone and There; she was my classmate and friend in high school and I got to know her work through the Of Soul and Joy program. I drew a lot of inspiration from these photographers.

"These guys were my friends, people I grew up with, some were people I had looked up to because they once were great photographers or dancers – before they got consumed by the drug"

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

The project which was shown at the 2017 Magnum AGM, which ultimately led to your becoming a Magnum nominee, was your Nyaope work?

The Nyaope project started in 2013. I used to walk around with my camera and take pictures of my surroundings. One particular day one of the guys who uses nyaope asked me to take a picture of him and his friends, who also smoke it. I went to see them. I have to say, I was a bit scared, because these guys are rejected by the community and they are sort of painted as monsters, almost everyone in the community does not want to associate with them. But I went inside their shack and started taking portraits of them. While I was taking portraits of some, the others were busy getting high, others were lying on the bed. There were like five of them that I could see, and some others I couldn’t, because they hid themselves. Afterwards I went home and looked at the pictures and was surprised at the access these guys gave me.

I went back to them and proposed that we start a project to raise awareness about the drug and bring some kind of change to their lives. I thought to myself that maybe if these images got out there someone would want to offer some help. Some of the guys had told me that they would love to go back to their old selves, before they became addicts. I hoped that that my images would ignite some kind of conversation in my community about nyaope. The drug has caused a national crisis in South Africa.

This project really affected me because these guys were my friends, people I grew up with, some were people I had looked up to because they once were great photographers or dancers – before they got consumed by the drug.

Your work on your sister is even more personal, can you explain a little about that?

My ongoing personal project about my sister, Ziyanda, is titled I carry Her photo with Me. Ziyanda disappeared for 15 years. The project started from a family photo; her face is cut out of it. It was the only picture we had that included Ziyanda in it, and we had to cut her face out for her funeral photo…

Ziyanda was a very secretive person. She never allowed people in her space. At the same time she was a very rough and rebellious person; this was also her reason for not wanting to be photographed. Just before she passed away my mother found Ziyanda in a local men-only hostel called Mshaye Aze Afe. When we found her she was sick. No one ever questioned her or spoke about her disappearance. I’ve never heard anyone mention her since, even during family events, birthday parties, dinners, Christmas, New Years… no one ever said that they missed Ziyanda.

"I started using photography to search for answers, to help myself heal and to make my family talk. It is an attempt at ending the cycle of people disappearing in my family"

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

This left me with blank pages full of guilt, because the last time I saw Ziyanda was when I got hit by a car. I was with her and she ran away, and I never saw her again. I needed answers. I needed to apologize and maybe find a way to forgive. I wanted to ask about her, but I couldn’t. I started using photography to search for answers, to help myself heal and to make my family talk. It is an attempt at ending the cycle of people disappearing in my family.

I’m also working on a collaborative project called Daleside, with photographer CyprienClément-Delmas. Daleside is a small town found in the Midvaal, south of Johannesburg. When I first visited Daleside, to me it seemed an isolated place, a ghost town. I first went because my mother used to be employed there as a domestic worker. During school holidays I could also go, assisting in the garden and making some pocket money. From the highway all you can see of it is a small school surrounded by trees. You would swear that no one lives there, it looks deserted. To my surprise, beyond that forest there were people, there was a community with all the systems that exist in any other. When I penetrated further I discovered a place with much history and culture.

Was the area’s racially mixed nature a key area of intertest for you, and did it present any new challenges?

Part of my interest in the community was because my mother used to work there, but also its background and the mixture of races living together. It used to be a white dominated area, but now it is mixed and this is visible in my images. It is a working-class area. Half of the people who live there either used to work in the mines or still do, the rest work on farms. It’s almost as if the countryside has come into the urban environment.

For me, when I’m with Clément-Delmas- my white, French, collaborator – it is easier to work there. But when I’m alone – when he goes back to France – it is a bit challenging for me. I have to constantly be careful how I approach people and their personal spaces. There was one case where I had to sign a document describing where I would use the images, this would never happen in the townships.

It takes a lot of energy and patience to get into these spaces. One of my strategies was to attend church there, so that the people in the community could see that I wasn’t there to cause any harm. It is a very Christian, conservative community. I sometimes even ask the pastor to explain to the people what it is I’m trying to do. This helps me make inroads.

The culture of the people of Daleside is very well preserved, and their community has social challenges very similar to those in my own. This helps me relate to them, to some extent, but there are also differences that make it difficult for me. As an outsider, most of the time I was mistaken for someone who was looking for a job. This wouldn’t happen if I was there with Cyprian. At times I’d also feel like I wasn’t connecting with them; for me it is important to connect with the people I photograph. I think it was because I kept being reminded that I did not belong there, even though I felt like I did because of those similarities I saw between our communities.

"It takes a lot of energy and patience to get into these spaces. One of my strategies was to attend church there, so that the people in the community could see that I wasn’t there to cause any harm"

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

How do you feel that your background, and growing up in South Africa, have dictated the direction your photography has taken?

I grew up in Thokoza. This is an area of the country with a history of violence, where political rivalry and conflict between the IFP (Inkatha Freedom Party) and ANC (African National Congress) can be likened to a war, one that left many families in a shambles and the community divided by black on black violence. I’m interested in the aftermath of the violence and oppression that took place in my country. People find different ways of dealing with trauma. People disappear and families are left incomplete. Others are lucky enough to find their family members alive. Because of the high unemployment rate the youth end up getting involved in undesirable activities. People suffer from mental illness and more black on black violence happens, such as the recent xenophobic attacks on black immigrants from other countries in Africa. People look at them as though they are taking jobs from locals, and other rumors spread… These flare up from time to time, sometimes as a response to other stresses in the community, other protests or issues. The last time was in 2013 or so, at that time it affected people who were close to me, my friends. All these factors have given direction to how I take photographs.

Looking at your work, there are a variety of approaches: color and black and white, still lives, constructed scenes, and traditional reportage work. But throughout all of these there seems to be a central sensitivity in approach, and a closeness to the subject.

I don’t want to be a stranger to my subjects. The relationship I create with my subject is more important to me than taking a photograph and leaving. I like to spend time to get to know my subject without carrying a camera with me sometimes, and for them to get to know me too. For me, making photographs within my surroundings and with sensitivity is part of the idea of Ubuntu; this is an African concept that loosely translates to “I am because we are”. I would love to experiment with more formats in the future. Sometimes you need other ways of storytelling that photography can’t convey.

How do you feel the projects you are working on, and hope to work on, are tied together – do you see a central set of themes in your interests / work?

My work focuses a lot on socio-economic themes. This could be mainly because these are the things that I see on a daily basis, these are the things that concern my community. For example, in my projects there is this sense of my subjects creating pseudo-families for themselves. You see it in Nyaope,with the families made up of drug users, and also in the project I carry Her photo with Me – Ziyanda disappeared and completely changed her identity, and found herself a new family.

The responsibility of a photographer is to be true to the people they are photographing and to be transparent in their interactions, because we photographers are dealing with people’s lives. I want to see my work opening conversations that result in solutions.