How To Get New Photographic Ideas

Philippe Halsman’s tips for developing creative photographic projects

The life’s work of late Latvian-American Magnum photographer Philippe Halsman is a masterclass in creativity. The photographer’s outside-of-the-box thinking resulted in creative compositions and genre-pushing takes on portraiture, from getting an actor to answer questions via facial expression, to making portrait subjects jump in the air.

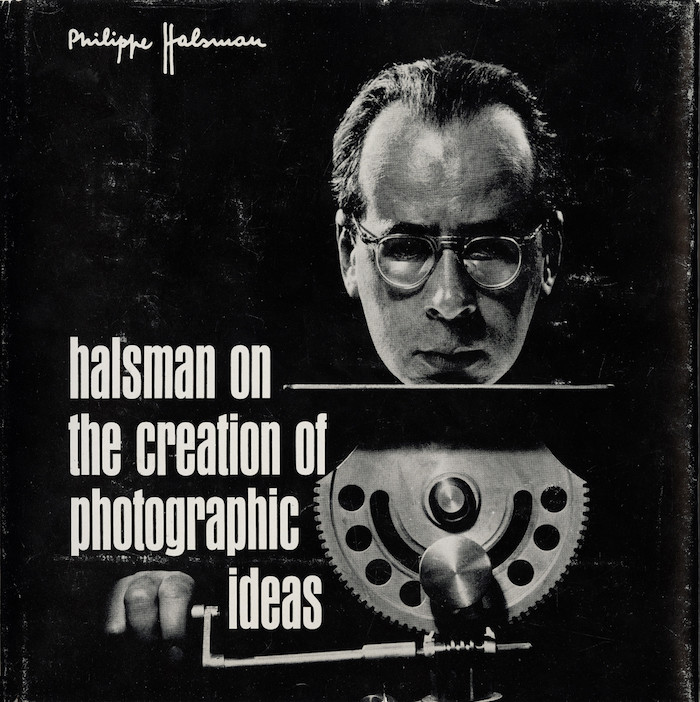

As a new year begins and photographers both new and seasoned look at their work afresh, allow Halsman’s wisdom to spark your creativity. A now-rare book published in 1961, Halsman on the Creation of Photographic Ideas, aimed to offer unpretentious, practical advice and inspiration for photographers in order to help develop creative approaches to their work, addressing a problem faced by photographers of all kinds.

“The problem of making a striking or unusual photograph is a universal one,” he writes, “commercial photographers need to create work that gets noticed, and editorial photographers need to interest readers. Even amateur photographers face this problem because they enjoy sharing their photos with others”, wrote Halsman, effectively predating Instagram’s ‘like’ feedback function by five decades.

The book is divided into two parts; Part 1 focuses on certain rules and rationales Halsman identified for making more striking photographs, such as taking a bold and direct approach, or employing unusual angles or dimensions; Part 2 delves further into the psyche of the photographer and provides some practical exercises and thought experiments designed to stimulate creativity. Here we present five take-aways – practical means to stimulate ideas and to spur you to approach your practice with renewed energy in 2019.

"The problem of making a striking and unusual photograph is a universal one"

- Philippe Halsman

Brainstorming

Halsman extolls the virtues of brainstorming, a relatively new concept in 1961, pioneered by advertising agencies. Participants in a “brainstorm” are encouraged to voice even their silliest suggestions, with the thinking being that they will in turn inspire further suggestions. Halsman was on the fence about the usefulness of this practice, but says that although he has never participated in a large group brainstorm, he finds that he is more productive when he discusses a problem with someone.

“One reason is psychological,” he writes. “You are not alone, but you face someone who serves you as a sounding board, prods you and expects an answer. The second reason is physiological. Your system is stimulated by the challenge of the discussion.”

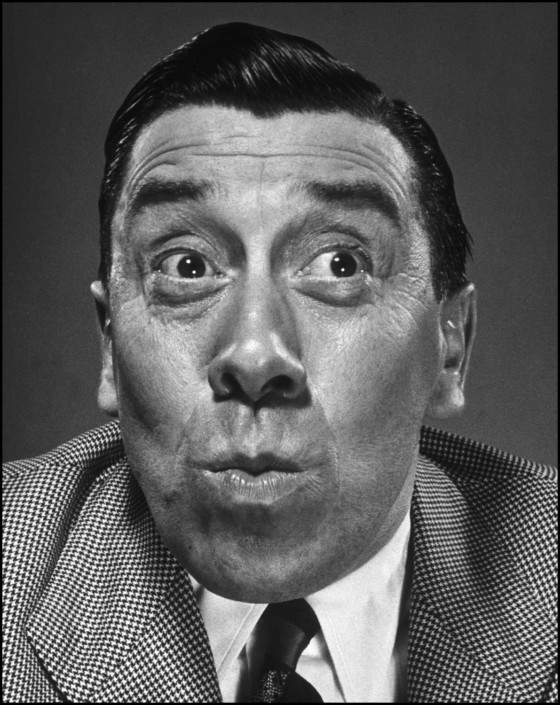

Halsman’s portraits of French actor Fernandel are a result of such a ‘prodding’ process. Having recognised the actor at a gallery, Halsman’s wife suggested he photograph him for a magazine. Halsman initially protested, thinking Fernandel was not well-known enough in America at that time, so his wife encouraged him to “make him known!” This then sparked the idea in the photographer to conceive of a photoshoot where he would ask the actor about how he is settling into America and he would reply with facial expressions.

Memory

“The roots of most of our ideas draw from the great reservoir of our memory,” writes Halsman. “Each book we read, each play or movie we see, each symphony we hear, each photograph or painting we study enriches our possibilities as an artist and as a human being. But when we put our memory to use, often we cannot avoid imitation.”

“When imitation means solely copying somebody else’s work, it is wrong and worthless. But when imitation means stimulation which develops something that exists and adds to its elements something that is new and personal, it is the kind of imitation that is responsible for the entire progress of our technology and civilisation.”

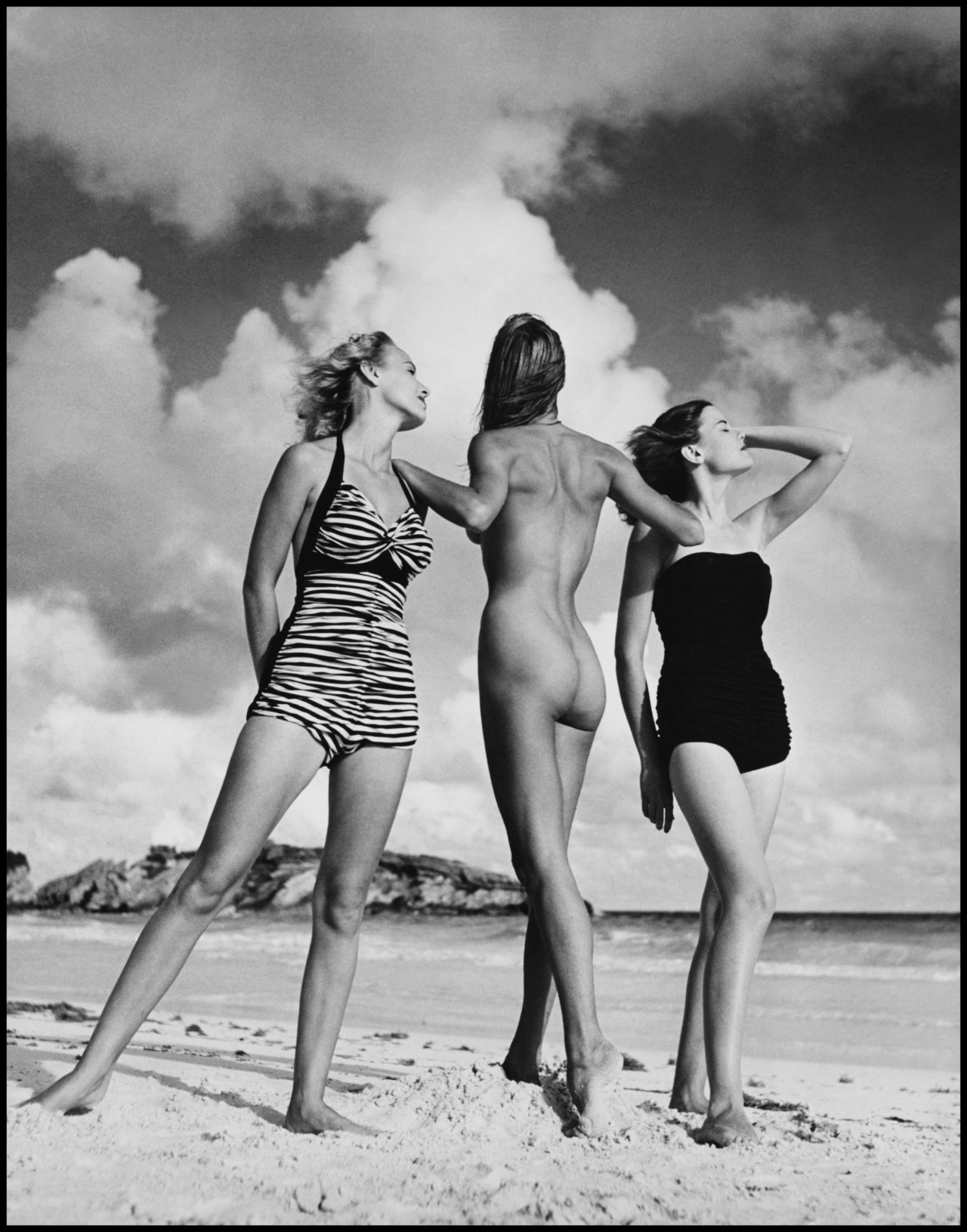

Halsman explains how Raphael’s “The Three Graces” informed his framing for a photograph he took of a group of three young girls on a beach. “I put the taller girl in the middle and asked her to protect the little ones”. The motif clearly inspired his work elsewhere, as another shoot at the beach featuring female fashion models takes a similar composition…“it is interesting to note that in his painting ‘The Three Graces’ Raphael imitated a then recently discovered Roman fresco, which in turn was nothing but a representation of a famous, since lost, Greek sculpture.”

Knowledge

The knowledge we have enables us to look “forth to the future effects which we can use in our photographs,” wrote Halsman, who in the 1940s, 50s and 60s was very much interested in new technology and experimental techniques he could use to make creative work.

“Once, on a Detroit proving ground, I was taking pictures of the latest models of the Chrysler line. The five cars–a Plymouth, a Dodge, a DeSoto, a Chrysler and an Imperial–were lined up for me on the test track. It was a dull-looking picture, and I felt a desire to shoot the cars rushing toward the camera. It would have been safe if I could have hidden the camera in a deep enough hole and released it electrically from the sideline. But I had only 15 minutes to make this shot–not enough time to dig a hole in a cement test track.

I filled my negative with the five cars, stopped down the lens completely, set the shutter on time and shouted, ‘One, two, three!’

At ‘three!’; the five cars went as fast as they could–backwards–I exposed for two seconds. Although I had never tried it previously, I knew beforehand that the film would not know in which direction the cars were moving. When the senior art director of the agency saw the photograph his first question was, ‘And what happened to the photographer?’”

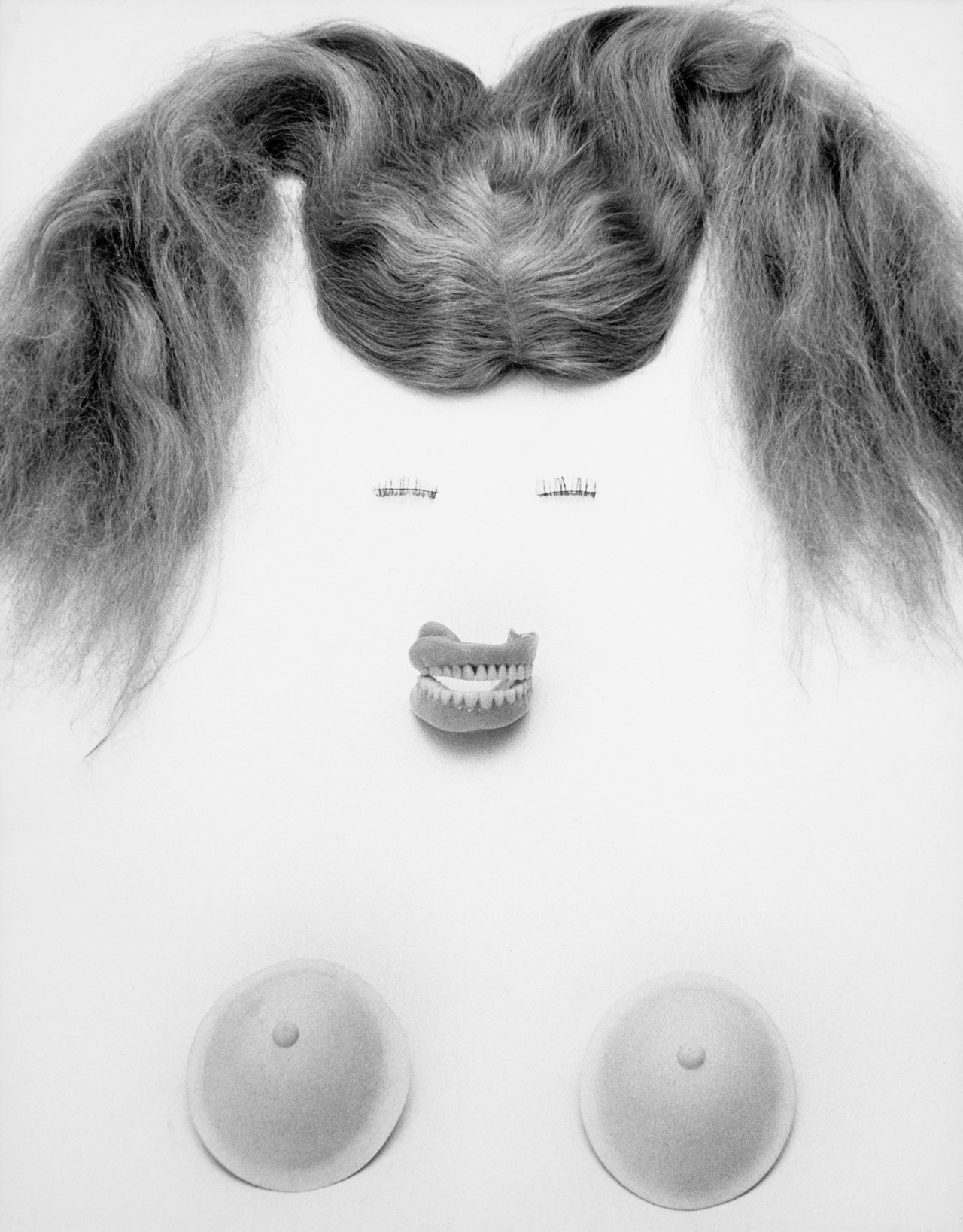

Objects

“A photographer sees more than other people do. He is always on the lookout for something interesting. Interesting objects cannot only make our photographs more interesting, but they are sometimes capable of stimulating us to make an unusual photograph. The recipe is: if you have such an object give some thought to it.

Once, after a portrait sitting, a glamorous Hollywood star left her paraphernalia in my studio: a couple of false eyelashes, a wig, and, naturally, a pair of falsies. They gave me an idea. I phoned my dentist and asked him to lend me some false teeth. I combined everything into an image which I called ‘The Essence of Glamour’ and photographed it.”

The Photograph

“It is interesting that a frequent source of stimulation is the finished photograph. How often does it happen that a photographer looking at the end result of his efforts exclaims, ‘Now I know what I should have done!’ Unfortunately, this stimulation often comes when it is too late to do anything about it,” wrote Halsman. “The obvious advice is: look for stimulation before it is too late. Try to sketch the photograph beforehand, or at least, visualize it in all its details.”

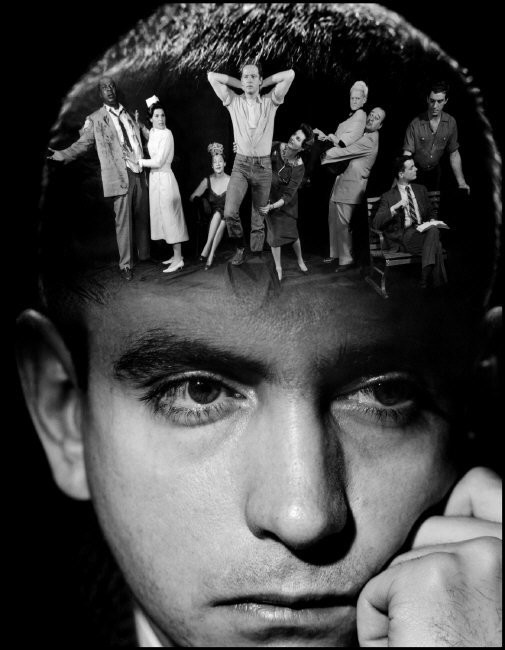

The photograph itself can also serve as further inspiration for the final image, as Halsman’s famous Jump project attests. “Jumpology”, a term coined by Halsman, posits that a person’s jump can reveal their true character. He realized this while looking back on a series of photographs he had taken of several NBC comedy actors. “Suddenly, I saw in these finished photographs that each comedian had jumped in character.” For example, Jimmy Durante “flailing his arms like a big-nosed bird” or Jack Carson, who seemed “a little too heavy”.

From then on, Halsman asked many of his portrait subjects to jump in the hope of revealing their personalities. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor shoot straight up into the air holding hands, while Marilyn Monroe tilts her head playfully, the fringe of her evening gown adding to the sense of movement. This body of work would become a book the book Jump, one of many classics still in print.

Get further under the skin of Magnum photographers, learn how they think and approach their practice with more Theory & practice articles here. Magnum’s new online education platform now also offers “The Art of Street Photography” which follows several Magnum photographers as they make work on the street, discussing the genre and their own unique approach to their practices.