The Grace and Tenacity of Martine Franck

The Belgian photographer worked relentlessly for more than 40 years, beginning with her first expedition to Asia in the 1960s

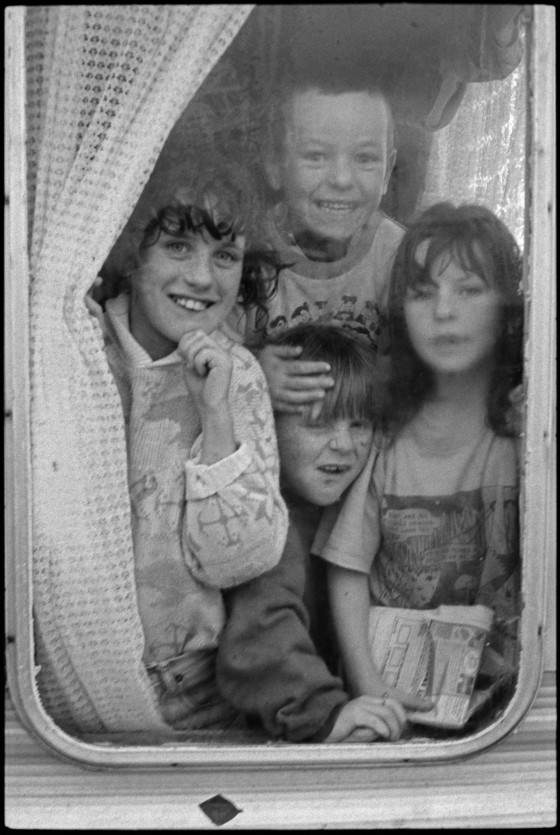

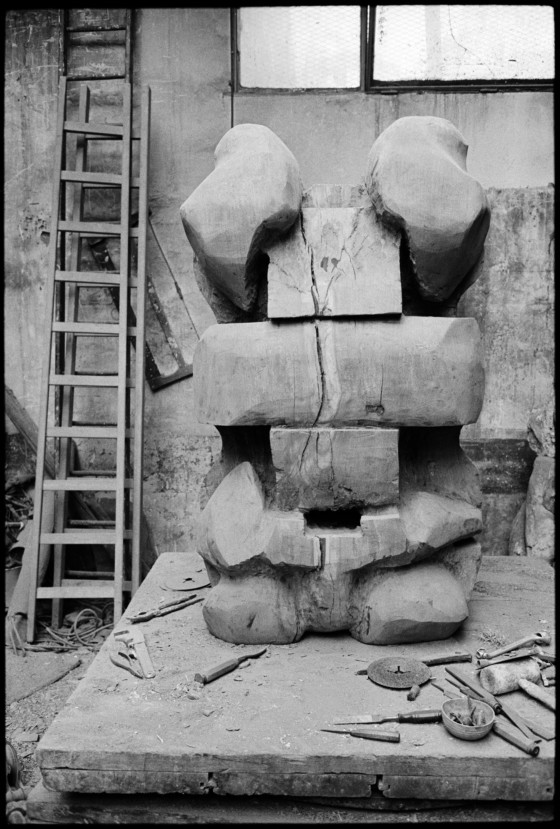

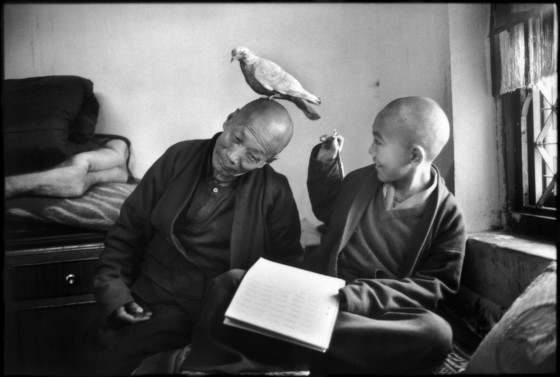

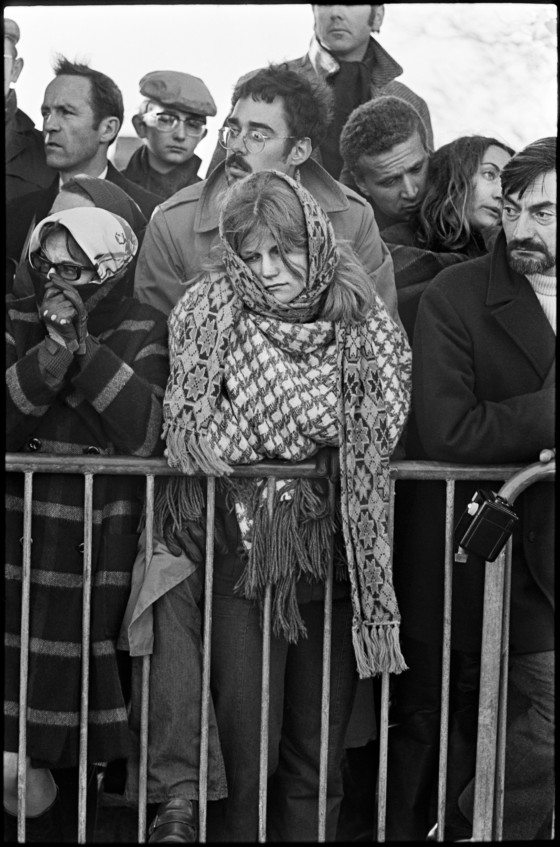

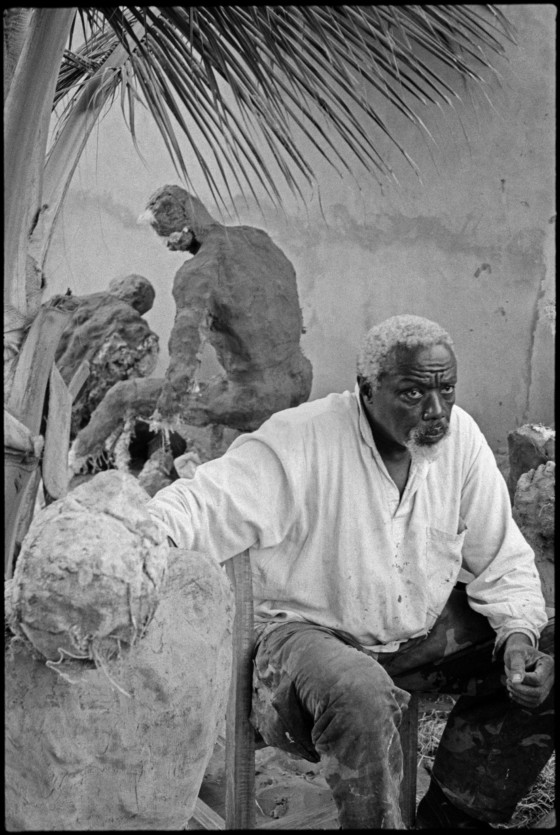

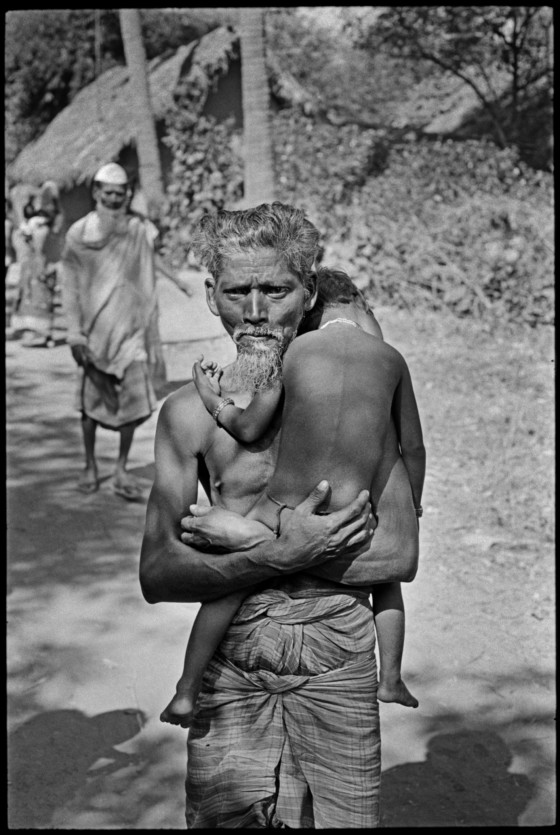

In the words of friend and fellow photographer Robert Doisneau, Martine Franck practiced her craft with the regard amical. This “friendly eye” inspired a trust and respect from those living on the peripheries of society—the elderly, the poor, the socially excluded—whom she was drawn to document. Franck explored worlds as varied as the women’s liberation movement, buddhist temples in Tibet, artists’ studios in France, and the industrial North of England. And with her sensitivity and deep fervour for life, she was always ready to greet the unexpected with an open, subjective mind.

“I feel concerned at what is happening in the world, and involved in what surrounds me. I do not wish merely to “document”, I want to know why a certain thing bothers me or attracts me, and how a situation can affect the person involved,” Franck said in 1980. “I am not looking to create a situation and I never work in a studio. Instead, I try to understand, to grasp reality. In photography, I have found a language that suits me.”

Franck was a giant of the humanist tradition and had a style and singular purpose, which she carried out with tenacity and grace. This talent was recognised by Magnum Photos (she became a full member in 1983) and her husband, Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson, who encouraged her to carve out her own path. She later became co-founder and President of the Henri Cartier-Bresson foundation.

As the retrospective monograph, Martine Franck, is published by Editions Xavier Barral, her legacy is remembered through the following edited extracts.

"All her work is shot through with the immediacy of her technique in black and white, combined with the clarity and meticulousness of her composition and framing"

- Anne Lacoste

Anne Lacoste – Direction, Institute for Photography Hauts-de-France, Lille, France

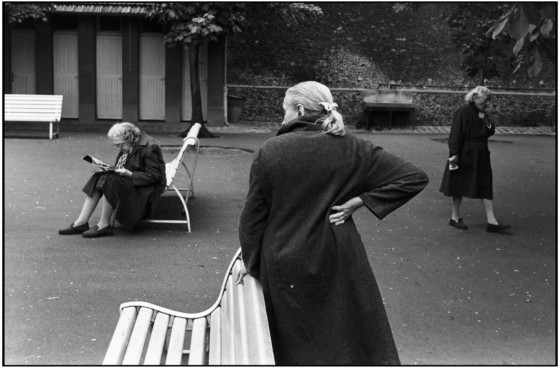

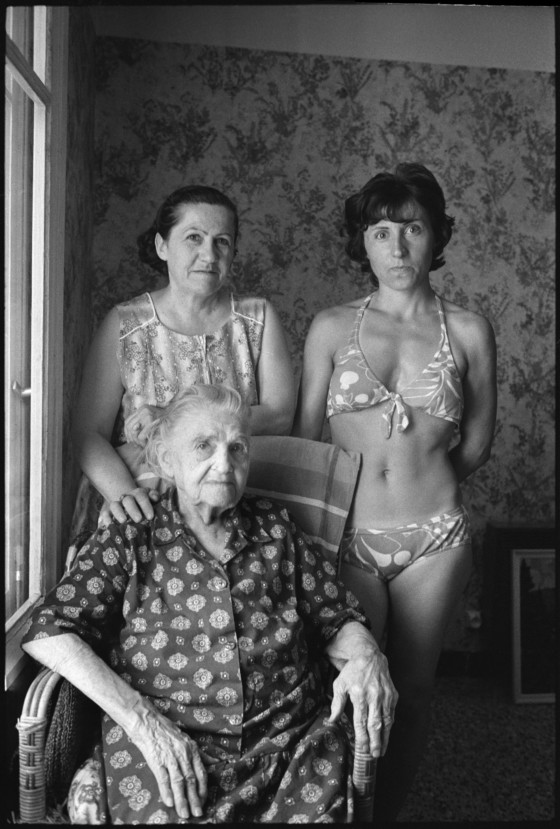

Martine Franck’s route to photography was a very personal one. Travelling across Asia in 1963–64 during her first long trip abroad, she began to explore the opportunities provided by the camera to get out and meet people and the potential of the language of photography to realise them. Over the next almost fifty years, she went on to amass an extensive photographic body of work dedicated to the human condition around the world, ranging from individual portraits to treatments of universal themes such as ageing. From the very outset, she formulated a unique approach to photography and she remained true to it throughout her entire career. All her work is shot through with the immediacy of her technique in black and white, combined with the clarity and meticulousness of her composition and framing, focusing on the isolated, self-sufficient image.

Her timeless images swim against the tide of the sensational highlighting a particular event, and the question of our understanding of time lies at the very heart of her work. It is evident in her project on age, which she pursued over several decades, and the titles of her exhibitions and published monographs: Le Temps de vieillir, De temps en temps, and D’un jour, l’autre.

"Martine Franck encourages us to take another look at the supposed banality of everyday life"

- Anne Lacoste

Martine Franck encourages us to take another look at the supposed banality of everyday life. Her archives reveal the quality of her eye, from capturing the moment to more reflective compositions. Working outside aesthetics trends, she established a corpus of work in which the camera was first and foremost a tool with which to understand the world. Conscious of her status as an ‘outside observer’, she pursued her private projects over the long term with a view to understanding them in all their complexity, while always maintaining the same respectful approach to the subject. Martine Franck, who defined her own experience of the photographic process as a ‘transgression’,47 perceived the image as a performative tool with characteristic humility, reflecting her own personality.

"Martine Franck proclaimed wonder, a profound joy in all humanity while struggling, more than anyone, against exclusion with all the empathy she employed so well."

- Agnès Sire

Agnès Sire – Artistic Director, Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris

Within the tribe of photograph hunters, Martine Franck cut a discreet, naturally elegant figure. Despite her husband joking that she was ‘not made to walk the streets’, she succeeded in conquering her shyness with the help of her camera and an unexpectedly bold streak. ‘It is the adventurous who are shy’, John Berger wrote to her, ‘but an antidote to fear is speed’.

A paradoxical figure due to her mix of grace and tenacity, Martine Franck combined an urge to bear witness with a desire to meet artists, and a preoccupation with composition with the quest for a calm simplicity in her portraits. The famous regard amical (friendly eye) proclaimed by Robert Doisneau goes hand in hand with the celebration of the unexpected and the importance of form. This respectful greeting addresses life: Martine Franck proclaimed wonder, a profound joy in all humanity while struggling, more than anyone, against exclusion with all the empathy she employed so well.

Martine Franck found exclusion repellent: the exclusion of women, of Tibetans, the elderly, refugees, the inhabitants of Tory Island. She became an activist in support of many of the causes she photographed, demonstrating great courage in a well-brought up young woman who had been taught not to cross boundaries. She explained: ‘The camera is itself a frontier… and to cross on to the other side, you can only get there by momentarily forgetting yourself.’

"An infectious empathy captured unfailingly in the faces of those she photographed. People are confident in her presence"

- Dominique Eddé

Dominique Eddé – Author

Martine Franck’s work and personality are very similar. Both are infused with the same humanity, the same simplicity, the same self-respect and respect for others. Unfortunately, no word exists to describe the exact opposite of ‘vulgarity’. ‘Distinction’ is not right and nor does ‘refinement’ convey the way in which she combined sobriety and kindness, a taste for life and taste itself. When she tells us that Henri Cartier-Bresson did not like excess but rather its opposite – structure and balance – we see the connection between them – the beauty of the balance that he saw in her.

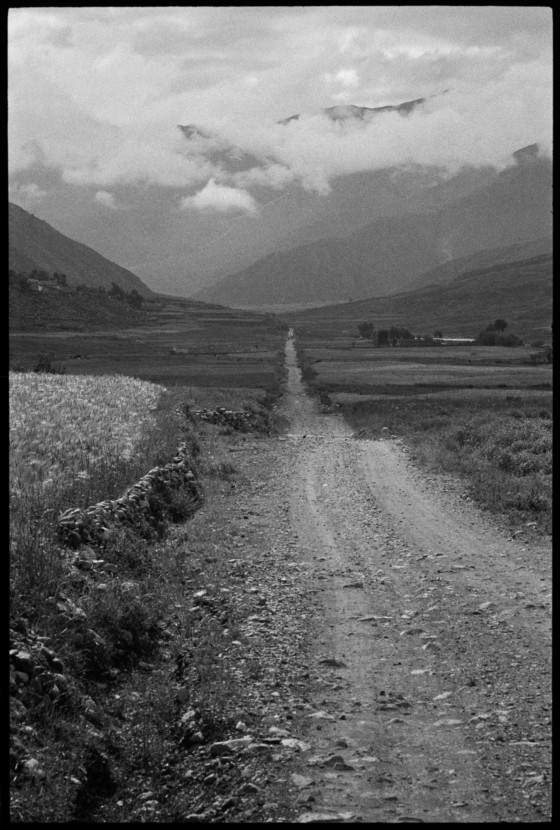

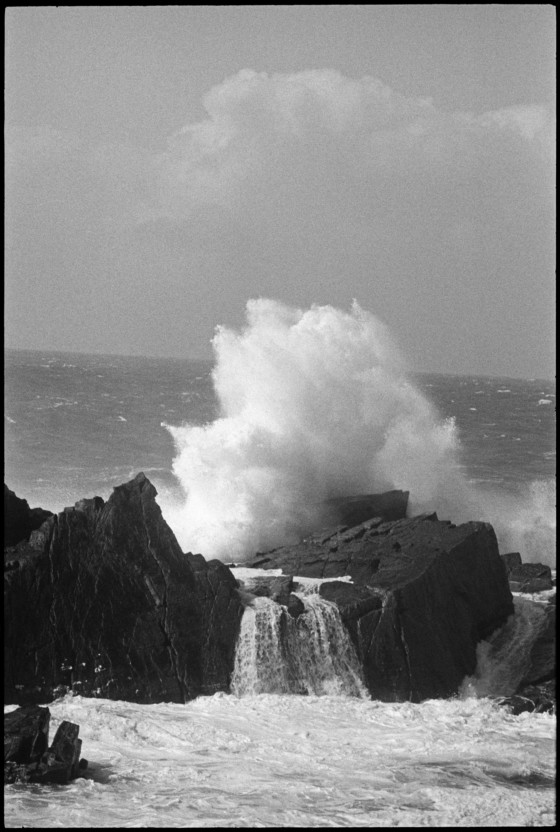

It is not by chance that Martine Franck felt naturally drawn to portraits and landscapes rather than places of suffering and conflict. In her view of the world there is a constant need for openness, for horizons. An infectious empathy captured unfailingly in the faces of those she photographed. People are confident in her presence. Freed from the need to pose. They are like her: inwardly and outwardly. So much so that in her photographs the instant decisif (decisive moment) is rarely implacable.

Martine is a humanist who knows what she doesn’t know and willingly ignores what she knows. What is her idea of happiness? In my view it is illustrated by one of her most beautiful images of two little girls making their shadows dance as they jump over a wall.

Martine Franck (1938-2012)

The monograph Martine Franck (which features unpublished images) can be purchased here.