Frida Kahlo’s Final Months

65 years on from the artist’s death, we take a look back at Werner Bischof’s portraits of Kahlo at home in the months before she passed

So many of her bold, beautiful and brutal self-portraits seem skewed towards surrealism, depicting their creator as a wounded deer, an architectural column, or even an open-chested anatomical study sitting opposite her identical twin. And yet Mexican artist Frida Kahlo steadfastly refused such categorization throughout her career. “I don’t paint dreams or nightmares,” she famously said. “I paint my own reality.” This reality, in life as on canvas, contained extremes of misery and ecstasy. But above all else, it contained pain, Kahlo’s constant companion from her early brush with polio as a small child through to the bus accident that she narrowly survived in her late teens, and which left her with health complications that dogged her throughout her life.

Perhaps it’s precisely the disparity between her painted and photographic likenesses that makes Kahlo’s image a source of such fascination today. What could be more revealing, after all, than to see both how somebody looks, and how they see themselves, side-by-side? Which is more real, which more accurate? Her stylistic and sartorial signatures – her thick braided hair, woven with ribbons and fresh flowers; her long traditional floor-length skirts, worn in part to conceal her deformed right leg; the defiant unibrow which framed her dark eyes – have become ubiquitous, recreated thousands of times over on postcards, stationery and even clothing. But if to look at her paintings is to embody her experience, visceral and unyielding, it’s in photographs of the artist that we can step back in search of objectivity. With a little distance, we see Kahlo anew.

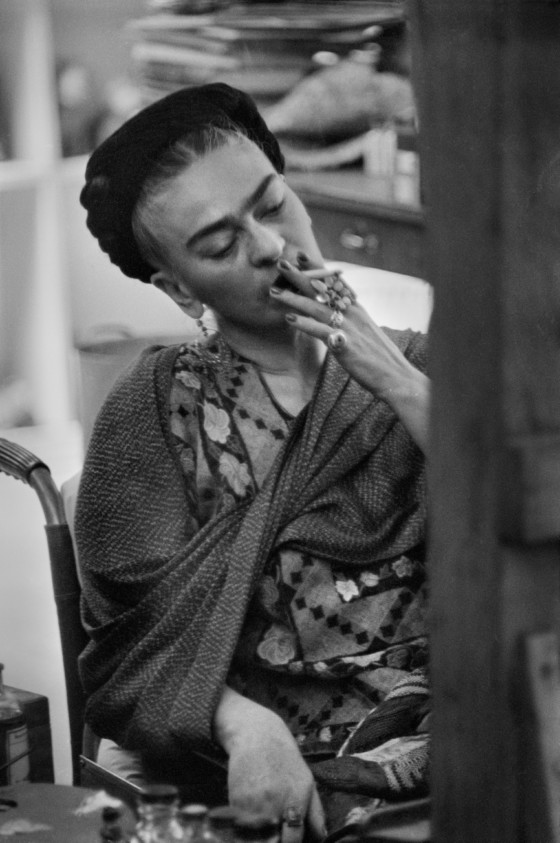

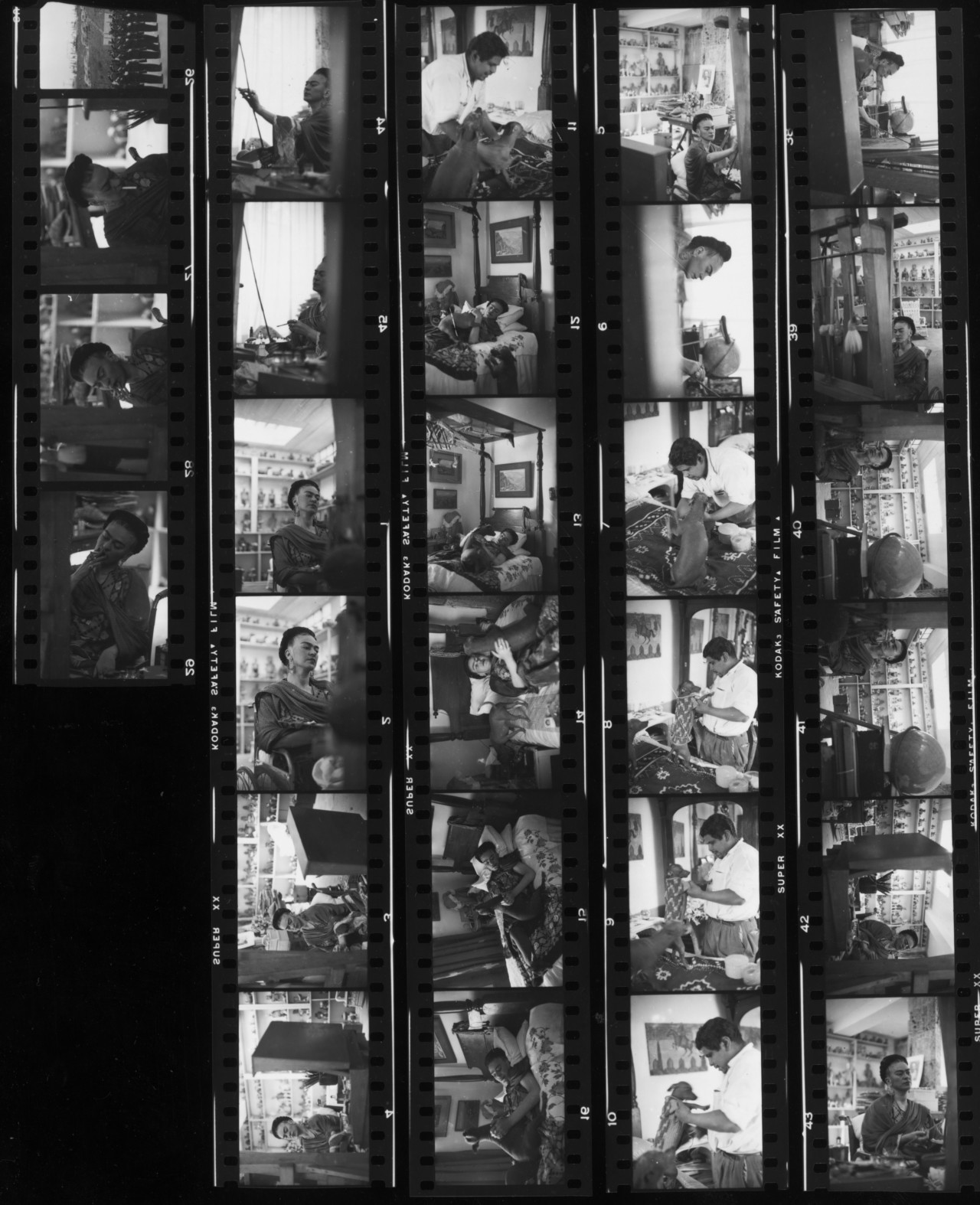

And never more startlingly than in the photographs Werner Bischof took of her at home at the Blue House in Coyoacán, Mexico, just months before her death from those previously mentioned complications relating to her old injuries. We can’t know why the Swiss photographer visited her in this time, or what they talked about, if they talked at all; whether they ate or drank, or whether Kahlo knew how little time was left to her. Through Bischof’s lens, the artist is instead pictured impossibly alone with her thoughts and feelings. She smokes while painting in her wheelchair, or reclining with a beloved dog. She is captured in amongst her collections of objects and oddities, which are clustered around the rooms she occupies. Kahlo’s life and work collide in these pictures; she appears at once beautiful and exhausted. It’s not so far, in fact, from the vision we see of her in her self-portraits.

"As a photographer and early Magnum member, Bischof dedicated his life to capturing beauty and suffering – a fact makes these images, so at home in his oeuvre, all the more poignant."

-

And while it’s Kahlo who is the focus of these images, she and Bischof share more common ground than a first look might suggest. Kahlo, for example, came to painting through photography; she learned to shoot and to process film in her late twenties, while assisting her father in his photographic studio. It wasn’t until she lay in bed a few years later, recovering from the bus accident that broke her pelvic bone and spinal column, that Kahlo turned her attention to painting, constructing a special easel over her bed so that she could work throughout her convalescence. On the other hand, Bischof’s first love was painting; he wanted to start his career as a painter when he went to Paris in 1939, but then World War II broke out and he had to go back to Switzerland, where he became an experimental photographer in his studio. One might argue that there’s a painterly influence in Bischof’s photographs, just as there is a photographic one to Kahlo’s compositions. But artist and photographer are united, too, by their early passing. Kahlo died at home in July 1954, at the age of 47. Bischof’s untimely death, due to a car accident in the Andes, ended his life in May that same year, at just 38 years old.

As a photographer and early Magnum member, Bischof dedicated his life to capturing beauty and suffering – a fact makes these images, so at home in his oeuvre, all the more poignant. “I felt compelled to venture forth and explore the true face of the world,” he said. “Leading a satisfying life of plenty had blinded many of us to the immense hardships beyond our borders.” He photographed traditional communities devastated by natural disaster, and landscapes forever changed through war. And in Kahlo, he documented an individual struggle, on a micro level; the scars of an extraordinary life underpinned by pain and suffering, and a slow surrender to existence beyond that. “At the end of the day,” as Kahlo once famously said, “we can endure much more than we think we can.” A fact which these images seem to serve as evidence of.

Explore more art by Magnum photographers here.