Sleeping By The Mississippi

On the occasion of its fourth reprint, Alec Soth looks back at his career-defining project

Much has been written about Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi. First published in 2004, it is a landmark publication in the Magnum photographer’s career, which propelled him to international recognition and notoriety. First editions of the photobook are highly prized items today. At a talk in London recently, in conversation with Sean O’Hagan, Soth reflected on the work, almost 15 years on, and how he began to make what would eventually become the tightly-edited tome, Sleeping By the Mississippi.

“I was a morose, introverted young man,” says Soth of his early years, identifying with a version of a Midwestern American sensibility that was “dark and lonely”. Working in a photo-processing lab on other people’s pictures throughout his early 20s, he had (almost) given up the ambition to become a famous artist, yet it was this very relaxation of his personal ambition that eventually allowed him the degree of freedom necessary to accept the influence of the American tradition of road trip photography in his own work – to stop pretending he was reinventing the wheel, to carry on the tradition and make it his own.

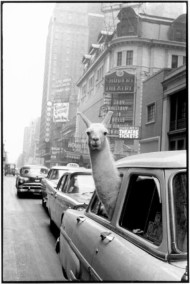

He began to follow the Mississippi River in his car, driving from place to place, letting himself progress towards locations he had vaguely researched and “using the river as a route to connect with people along the way.” These were the early days of the web and the development of his process ran parallel to the growth of the internet. “It was like web surfing in the real world” he says, “it was like trying to ride a wave.”

He drove from location to location, going from one thing to another, with a list of keywords for things he was interested in taped to his steering wheel; Soth’s aim was to stop his car as soon as something caught his eye, but he found that what had captured his attention was not necessarily the stuff of pictures he wanted to make. “Often these are photo clichés, things that look like work by another photographer,” he says. He first needed to weed out these well-trodden tropes in order to find the personal, the things that would allow him to honestly carve out his own meaning and make pictures.

“A miraculous time in my life,” is how Soth describes this process. He felt warmly welcomed in the region; he was allowed into the intimacy of people’s homes. Hyper-alive to the world, Soth had in fact just spent an intense month-long period with his mother-in-law, who had become very ill. He lived with her in her house as she died.

The symbols of religion he encountered everywhere in the American South, and which pervade his photographs, felt especially loaded. As the Mississippi goes south it becomes warmer and more open, he explains – he was photographing a melancholy landscape where he could visibly see the roots of the country music that was born here. “It’s so easy to be ironic and cool but the real stuff is still out there,” he says.

The most often-asked question people pose Soth is how he approaches strangers to take their picture. His response, unsurprisingly, is that it has changed over time. Describing himself as “painfully shy” in his 20s, he knew he had to get over his timidity in order to photograph people; yet he found this very same shyness – coupled with his huge large format box camera and its accompanying tripod – disarmed his subjects, and allowed him a way into their private spaces, following his desire for a deeper intimacy. The experience of living with his mother-in-law is one that he credits as “giving him superpowers” – talking to strangers was nothing in the grand cycle of life and death. And photography was “a permission slip” – a reason for being there, for entering the lives of strangers, and taking their picture.

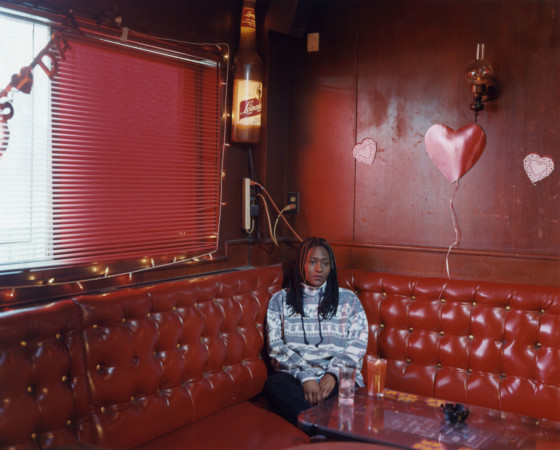

Portraits populate Sleeping by the Mississippi; characters imbued with a kind of mythological meaning, Soth’s images have rendered them mysteriously symbolic. Charles – perhaps one of the more well-known characters to inhabit the book, with his aviation gear and model airplanes – represents a “humble search for creative exploration” to Soth. “I want to be him!” he exclaims. To the photographer, at the time, Charles was proof that “living a creative life doesn’t have to be on an epic scale.

Yet, Soth isn’t particularly comfortable with the role of portraiture within his practice. “The great struggle with portraiture is the energy of discomfort,” he says, referencing the work of Diane Arbus. Ethically, Soth doesn’t relish this sense of discomfort: he sees in it a sense of exploitation of the subject, their race or their sexuality. He emphasises the reductive potential of photography, that what we see in his images are the exteriors of those people he photographed on a particular day, frozen in time and space and rendered two dimensional. Opposing essentialism, he doesn’t believe photography can convey a deep truth about a person. Instead, “a photograph merely is light reflecting off a surface” – a transient moment in time, impermanent.

Soth recognises photography as a language: a language full of dialects, of which road trip photography is one, with its own grammar and vernacular, its set of references. He acknowledges the influence of Robert Franck on Sleeping by the Mississippi, and the influence of other photographers whose work he loves on his choice of working with large format, such as Nicholas Nixon and Sally Mann. Crafting each shot was important and magical, “a very expensive magic” he laughs, noting the elevated cost of large format film and processing. Having to be very deliberate about each shot of course impacted his process, and delivered the thoughtful, deliberately composed style he is now well-known for.

Wryly, Soth observes that first photobooks are often a photographer’s best book project; often they contain many years of work before a photographer starts producing them more regularly, as the market demands new work. “Sleeping was full of joy for me and I loved making it,” he recalls, in contrast to later books such as Niagara (“it was such a struggle and I was rejected all the time – it’s not happy work”) or Broken Manual, which was about wanting to run away and disappear. Reflecting on the title, Sleeping by the Mississippi, he still sees in it a more lyrical way of moving through the world that hints at sleep and dreams. And indeed, “Sleeping is more about dreams and longing than it is about what is going on in America right now.”

A small number of signed copies of Sleeping by the Mississippi are available in the Magnum Shop, here.