David Hurn and Martin Parr: How to Build an Art Collection by Swapping Prints

Ahead of the opening of David Hurn’s Swaps exhibition, curated by Martin Parr, the Magnum photographers and print aficionados share their love for photography and their passion for collecting

Magnum Photographers

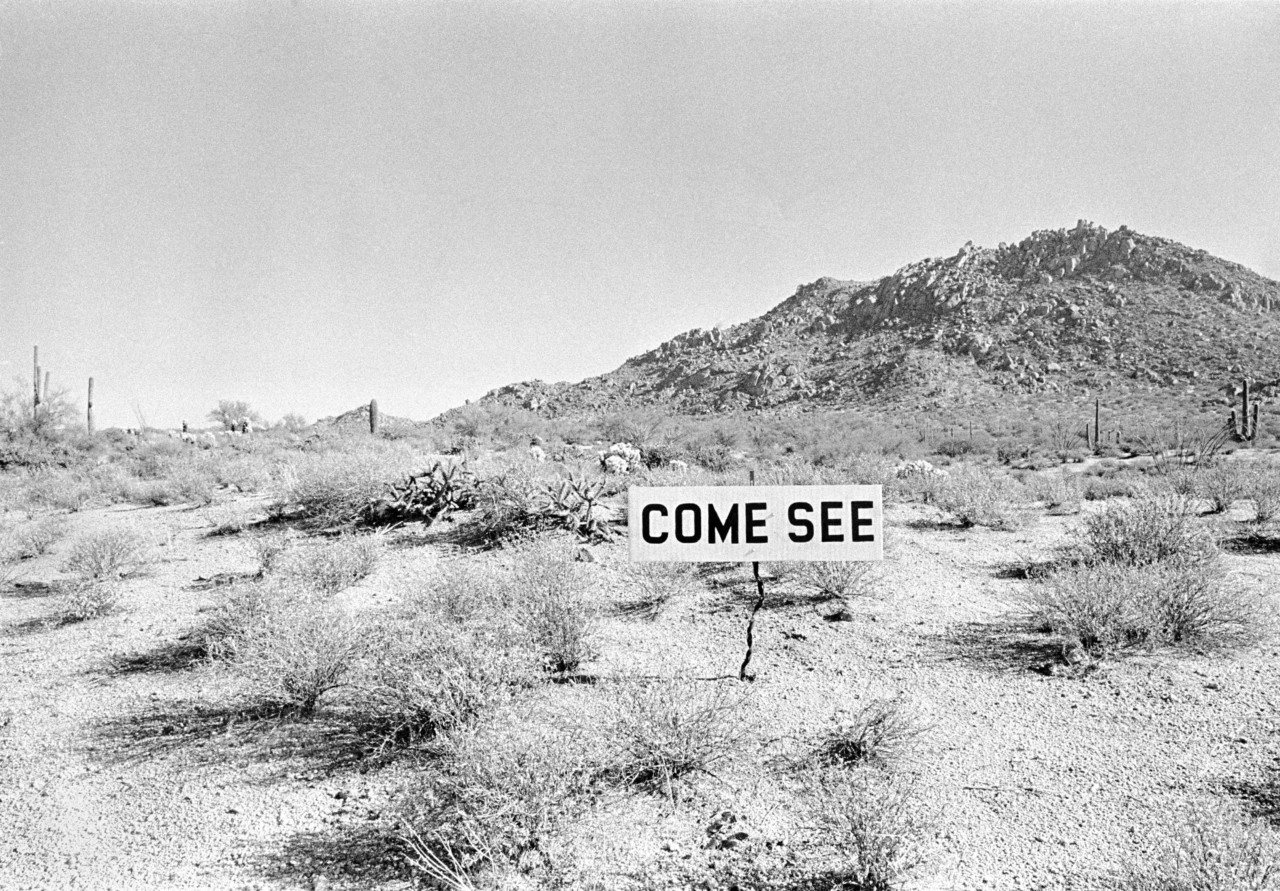

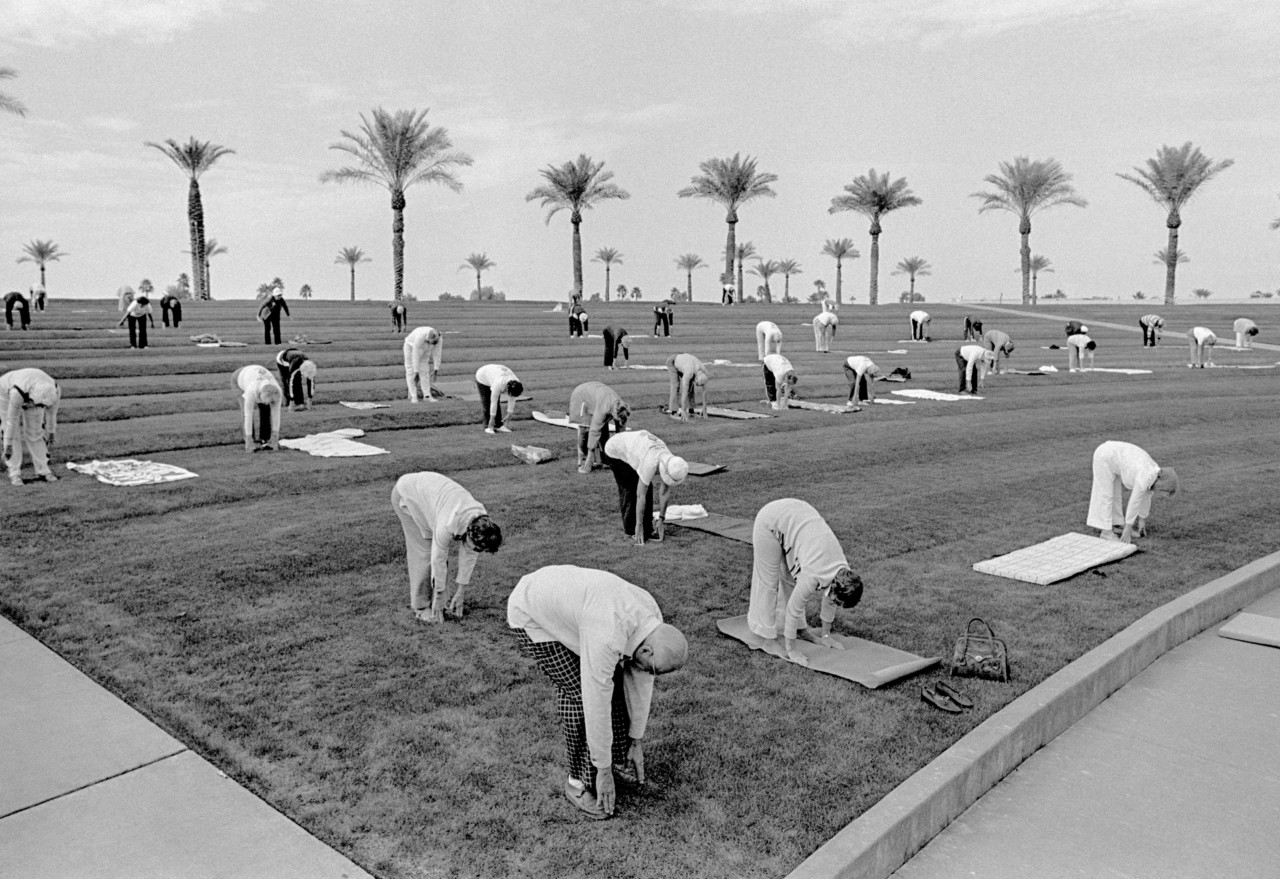

Magnum photographer David Hurn has, over the course of an illustrious career documenting stories as wide-ranging as the Hungarian revolution, the Beatles, and his Welsh homeland, assembled a deeply personal collection of photographs by exchanging prints with the fellow photographers he came into contact with over the decades.

Through his charming and dedicated engagement with photography and the photographic community – he established the well-regarded School of Documentary Photography in Newport, Wales, and joined Magnum Photos in 1965 – Hurn is a pivotal part of photographic circles and his requests to swap prints are a flattering entry into these.

Parr, the curator of an exhibition showcasing Hurn’s wide-ranging collection, notes “One of the first e-mails any new nominee will receive, on being accepted by Magnum, is from Hurn, inviting them to exchange. Everyone always willingly agrees; they select their favourite Hurn image and vice versa.” In conversation with the two Magnum photographers, we explore how their shared passion for photography has yielded noteworthy collections that inspire generations of photographers and collectors.

The impulse to hold and to collect: a work of the imagination

Contrary to the financial innuendoes that often accompany the descriptions of noteworthy art collections, the impulse to collect is rooted in matters other than pecuniary. Indeed, when Hurn began his collection, photographic prints had no monetary value whatsoever. In the early Sixties there were no photography galleries (the first gallery devoted entirely to photographic works, the Photographers’ Gallery, opened its doors in 1971), and, as Hurn explains, photographs only had a value if they were printed in a magazine. The print as an object was a useful tool for photographers to share their work, but not a currency.

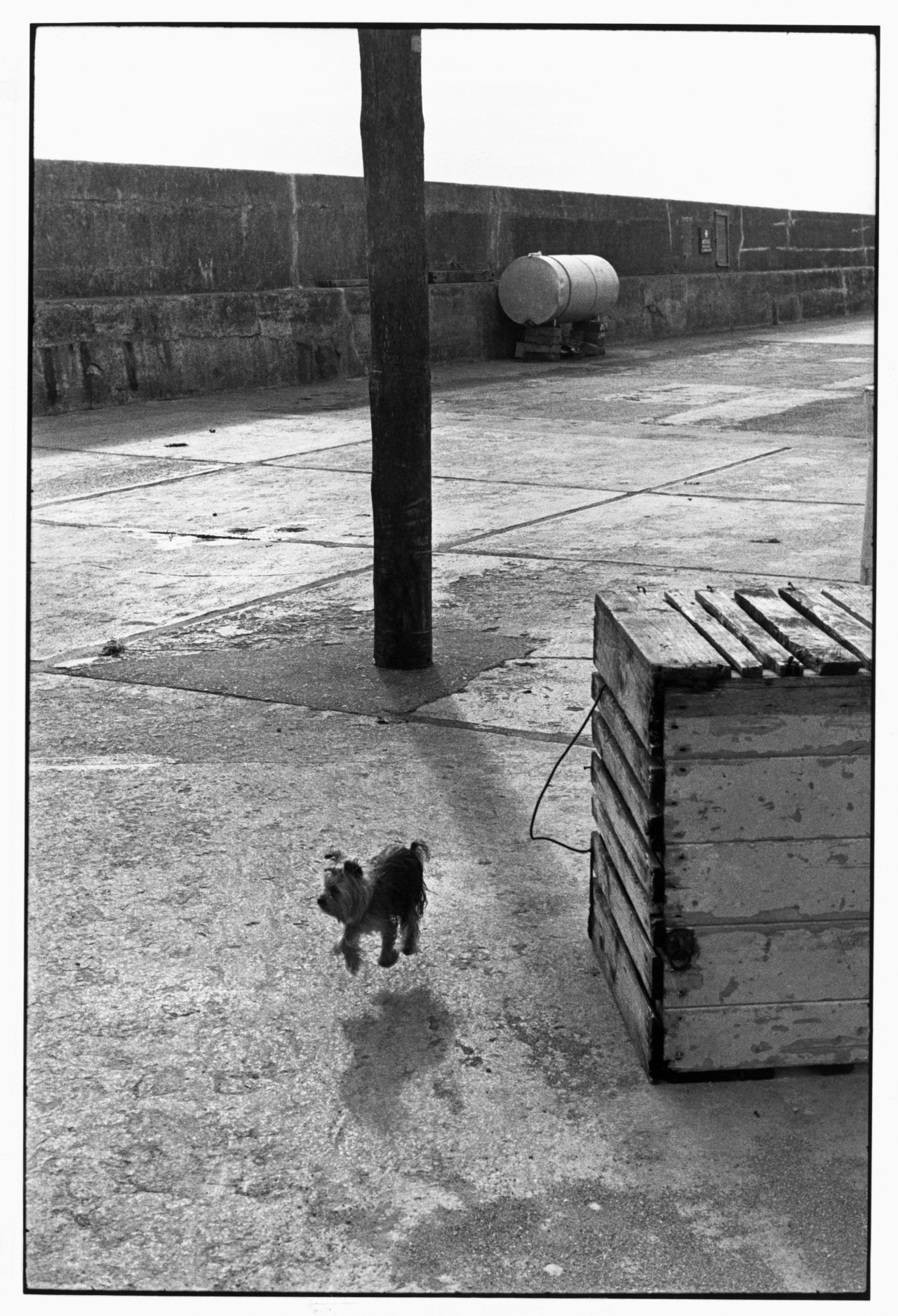

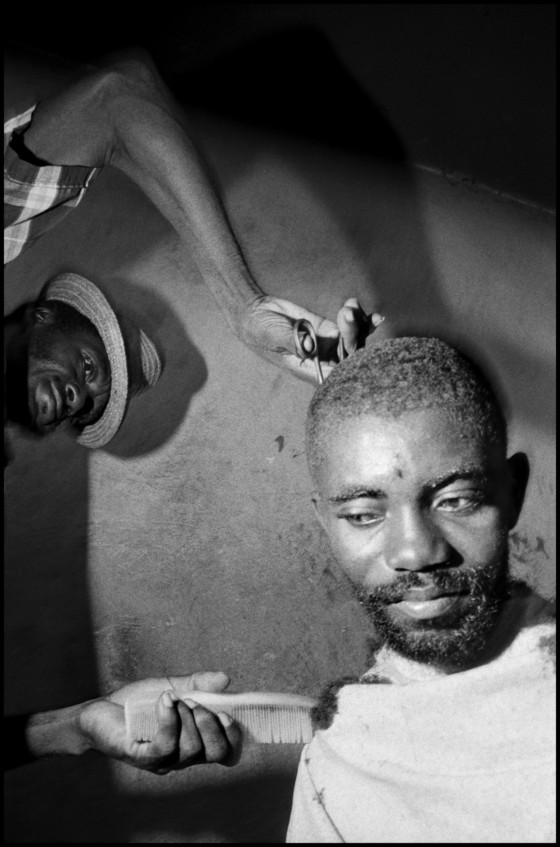

Hurn almost reverentially describes the experience of looking at a print as wholly other to looking at an image in the context of a magazine or a photobook: the romance of the printed photograph as object is one that creates a metaphorical relationship between the photographer and the viewer.

He expands: “When you handle a print that you know the photographer has actually handled and the photographer has deliberately chosen because it’s an important picture, it’s amazing how you can almost read them into the picture. It’s amazing that you cannot not read them into the picture. The handling of a picture you really love is very different from any other viewing of that picture.” For Hurn, the experience of holding and owning a print is a work of the imagination, and collecting photography is a wholly romantic endeavour.

“If I don’t collect it, no one will,” says Martin Parr, of a personal history of collecting, which began with fossils and bird pellets displayed in his first ‘museum’ in the cellar of his childhood home in Chessington, followed by stamps and coins, and of course, now, famously, postcards, photobooks and prints. For Parr, collecting is “a way of making sense of the world… a part of my DNA, whether I like it or not.”

Beyond prints, both have an affinity for the saving the ephemeral, in particular postcards. Hurn owns the world’s largest collection of postcards containing images of cameras. “Sometimes they are very obscure,” he says. “You’d see a picture of a crowd somewhere, but if somebody in there has a camera, I can collect that postcard. I have about fifteen hundred of them.”

Parr’s eye for the quirky and interesting is complemented by an “obsession with photographs” and a desire to support British photography, especially the work of those photographers he thinks are underrated: “when I began to have extra income I was able to support them indirectly by buying their work,” he says.

Building a collection through swapping and friendship

Hurn and Parr are fast friends. They have a deep liking and mutual respect for each other. They have known each other since before Parr joined Magnum; in fact, Hurn was “almost literally the first person” to buy a Parr print, for a fiver (£5), from his 1975 show at the Arnolfini, Bristol’s Centre for the Contemporary Arts. They share a love for the work of Sergio Larrain; in fact, the first prints Hurn owned were given to him by Larrain.

When Hurn ran the Newport course, where Parr taught, their conversations turned to their shared love of photography. “I’ve always respected the fact that he’s a real person that believes in photography,” Parr recalls. What is at the core of the friendship is a shared passion for photography and a “core belief in a great photo” – “this is life and death stuff for us,” enjoins Parr. Little surprise, then, that Hurn says of Parr, “One of the reasons I love him so much is that he gets so involved.”

Since that first purchase, the pair have done multiple swaps and Parr describes Hurn’s collection as “staggering.” Their latest exchange? A pair of photographs of Tenby, where Parr has an apartment, and where Hurn once photographed the beach in a way that Parr describes by exclaiming, “Bugger me, I wish I had a shot as good as that!” Now the print is on Parr’s wall.

“I just don’t understand why more people don’t do it,” cries Hurn, about swapping to collect. His advice to students is telling: “if there’s thirty of you on a photographic course and you’re there for three years, if you each swap one print with each other a year which you really like, when you leave college you would have a set of a hundred pictures. Not only would you have this very nice set of pictures, but you would have a memory of the other people on the course as you looked at them. It just seems so positive and people don’t do it. It’s very strange.”

Gaining the confidence to swap

In the early stages of his collection, Hurn would simply ask for a print. They had little monetary value then, and his request was flattering. Hurn didn’t offer his prints in return, because he wasn’t sure the recipient would actually like to receive one. It wasn’t until Elliott Erwitt asked him for a picture that he gained the confidence to initiate an exchange of prints.

He remembers, “I had asked him for a couple of pictures, and then he asked me for a picture. Which kind of threw me a little bit. There’s no logic saying that it should have thrown me, but I guess when you’re around somebody like Elliott, he is such an extraordinary personality of a photographer, you wouldn’t think that he would want something that you’ve done.”

Hurn explains that, “one of the reasons that I went from swapping one picture to two pictures was partly because I suddenly had the confidence to do it. I’d been around enough to start thinking well maybe people would like my picture. This isn’t a totally one way thing.”

He continues, recalling the early days of Magnum and the confidence that gave him in his own work. “Then, of course, I actually came into being an associate in Magnum. That in itself gives you a lot of confidence, because if you’re not totally stupid you realise that there’s a group of photographers, and you look around this room and realise that there is Bresson, and George Rodger, and Marc Riboud at that time, and Erich Hartmann and Erich Lessing, and Eve Arnold… Boy oh boy! And when they more or less turn around and say, ‘We would like you to join us,’ that’s pretty momentous, and it gives you confidence. More or less from that point on I started to swap as opposed to just ask people if they would give me a picture.”

The editing process: looking for authorship

David Hurn explains that when he asks someone for a print swap, he is only really interested in his selection of their pictures, which renders his collection a deeply personal one: “I wanted to have authorship of what I like about the people’s pictures,” he says.

His process includes a long period of discovery, figuring out what it is about the work he likes, often spending dozens of hours researching a fellow photographer’s archive. He makes sure he’s prepared for meetings: “I can actually rather flabbergast them by saying ‘Oh, I particularly like this or that!’ That’s a very flattering thing for somebody else to hear.”

His deep knowledge of the oeuvre of his fellow Magnum photographers has resulted in three photographers, René Burri, Josef Koudelka, and Bruno Barbey, requesting his edit of their work to be published in Magnum Magnum, a tome published in 2007, where each photographer is represented by half a dozen images chosen by a fellow Magnum member.

Faced with the immensity of the archive, Hurn finds interesting ways into the work, looking at books and portfolios to inform his selection, intuiting by these existing edits what “[Burri] thought were his best pictures. And then within that, obviously he’s a great photographer, it’s not going to be difficult to find pictures that you particularly like.”

Parr agrees, commenting about Hurn that “he has very good taste and has often chosen pictures that aren’t obvious … he has a great knack for finding images hidden in peoples’ archives that are strong, which have perhaps been overlooked.”

Hurn, with his deep knowledge of the history of pictures (which he consciously separated from the history of photography), makes a vivid comparison of authorship in photography to authorship in music and in painting. It is “so very curious and unlikely” that there should be such a thing as recognisable photographic authorship when everyone starts with the same thing, “a box with a hole in it.” And that is what Hurn is looking for.

Permanence and impermanence

When hard-pressed to name his favourite swap, Hurn tentively puts forward a Cartier-Bresson portrait of Matisse, with a personal inscription by Bresson dedicating the print to Hurn, highlighting once again the very personal nature of his endeavour.

Both photographers have very specific ideas about what will happen to their collections. Hurn explains, “as these pictures were swapped on a very personal level, I decided very early on that I wouldn’t or couldn’t sell them. That’s the cross I bear, that terrible puritanical Welsh guilt. It was written in my will very early on that the pictures must be kept together and donated somewhere.”

Parr is opening a foundation in Bristol which will eventually hold his collection and contine to support British photography, while Hurn is donating his collection – the full 700 prints – to the National Museum in Wales. “It was very powerful in my early memories. It was a place that my mum used to take me to when I was four or five, and I remember things about it. It’s lovely… If I was broke I might think differently about selling them, but they are all going to go there.”

"I don’t believe we’re unimportant, but I don’t think we should get too pompous"

- David Hurn

Not that photographic prints are Hurn’s most treasured possessions, anyway. That is reserved for other, more personal, objects, that remind Hurn of humanity’s transience. One of these is a piece of the oldest rock in Wales which Hurn brought home from the top of a mountain. The size of a cricket ball, he displays it in his home mounted on a plinth, recalling that Henry Moore once said “’Sculpture is anything that you can put on a plinth’… So you can change the rock from being just a rock to being something sculptural that you can look at. It’s almost my most precious thing that I have in the house.”

Hurn goes on: “I look at this rock and I think, that’s been here seven hundred million years! It wonderfully makes us all seem feeble and unimportant. Now I don’t believe we’re unimportant, but I don’t think we should get too pompous. We are very tiny specs in nature. It will go on, if we blow ourselves up, or get too hot and all that, nature couldn’t care a bugger… It will just be that we who think of ourselves as clever will be the ones who won’t be here, which I think is very funny!”