Derek Jarman’s Garden

25 years on from the English filmmaker and writer’s death, author Luke Turner muses the significance of Derek Jarman’s Dungeness haven

Magnum Photographers

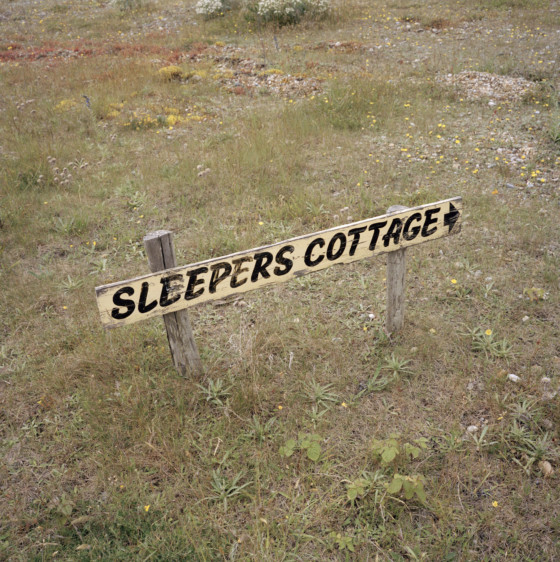

The above image, by Peter Marlow, is available as part of the Art Fund’s crowdfunding campaign to save Prospect Cottage and to protect Derek Jarman’s legacy.

The photograph, Overalls drying in Derek Jarman’s Garden, 2005, is available for two more weeks. Find out more here.

Seen from an aircraft descending over the channel to land at Gatwick, the shingle peninsula of Dungeness juts into the sea a strange, striated grey and beige, like an ineffective comb-over. The land of Romney Marsh behind it might have been reclaimed for grazing, but it nevertheless has the air of a barrier, a Stygian dampness, between the mainland and the trillions of tones of dry shingle of the peninsula. Is this a point of arrival from the sea, or a place from which to retreat from the land, a site of a last stand?

In this contested zone, where fences catch storm-blown litter, Derek Jarman discovered in the deep brown timbers of Prospect Cottage a haven away from the antiseptic wards of hospitals and the equally sanitized British film industry in (and frequently against) which he fought so valiantly for his art. Yet unlike most seeking a rural getaway, it wasn’t a place where he would rest on his laurels. It’s in the name of his home after all – Prospect, a looking out, towards a future. Here Jarman would devote himself to his lifelong love of gardening, and in time become genius loci of these few square meters off the Kentish coast.

There’s the garden around Prospect Cottage, and then The Garden, the 1990 film in which the Dungeness landscape became the stage for an outpouring of rage as Jarman reimagined the life and death of Christ as an allegory for the persecution of gay men. I imagine more people have made the pilgrimage to visit the garden than have sought out The Garden, still marginalized as an art-house film from a ‘difficult’ director, shunted off to the queer cinema ghetto. Look at the area on Google maps, and Prospect Cottage shows up as a camera icon, a tourist destination, while so many of the dwellings around show pink – now mostly high-end holiday homes, designed in a modernist style. It feels incongruous, for the garden was as radical as the avowedly anti-consumerist The Garden (there’s a scene where the hanging Judas is a credit card advert) and the man who made them both. Just as Jarman made a bonfire of what was acceptable in film, so he was a revolutionary in gardening. He described the lawn, that symbol of Middle England, as “against nature, barren and often threadbare. For the same trouble as mowing, you could have a year’s vegetables: runner beans, cauliflowers and cabbages, mixed with pinks and peonies, Shirley poppies and delphiniums; wouldn’t that beautify the land and save us from the garden terrorism that prevails?” He wrote that his work in the garden would be “disrupting its wildness as little as possible”, understanding with his director and set-designer’s eye that in this harshest of English landscapes gardening is a dialogue with place.

Any gardener must be a visionary, to take a blank space and foresee what might grow there, and the alchemy of water and light that will be required to make it so. It wasn’t just plants, either. Jarman’s diaries are full of accounts of flotsam washed up on the stony shore finding a new purpose amid the purple iris, valerian and columbine. This collage of metal, wood, flint, shingle, stone and fauna is land art with ancient roots. In the henges of flints and spiral formations – photographed in the low sun by Stuart Franklin – are visual echoes of the monuments and carvings in stone that the past peoples made in a time when morality and convention might have been so different.

"This collage of metal, wood, flint, shingle, stone and fauna is land art with ancient roots"

- Luke Turner

Yet Jarman’s entire life was one of collage, where the garden sits as an equal to filmmaking, exquisitely produced notebooks and journals of his intensely lived existence. It’s no wonder that it would become a film set, used in The Last Of England and War Requiem before The Garden, arguably his most visionary work. In its angrily psychedelic 95 minutes, Dungeness is populated by leather queers, smoking transvestites, fishermen, a dozen old women ringing wine glasses as the Last Supper in place of the apostles, and Father Christmases brusquely singing God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen. How often can you travel to a film set long after the cameras have departed? Well, you can visit The Garden still, and often feel as if Jarman is still present, conjuring. When I was last there, in the dead of winter some years ago, a man dressed as Santa rode a sputtering moped adorned with reindeer antlers and tinsel up and down the single-track Dungeness road, passing the severed head of a cod leering up for the tarmac.

In The Garden, two white shirted boys kiss in the shadow of a fishing boat stranded on the shingle, for Jarman knew this was a landscape of tenderness as well as pain, equally Eden and Gethsemane. Here on the edges of England, Jarman explored its paradoxes, the repression and homophobia, prejudice and conservatism, but also a twisted humour, complex relationship to the erotic, and a history that might be up for reclaiming. Both film and that little patch of land around the brown-stained, yellow-windowed cottage fight and provide respite from Thatcher’s England, which is why his work remains resonant today. In her time so many of the seeds of our contemporary predicament were sown.

"Old age came quickly for my frosted generation"

- Derek Jarman

Bleak, wilderness, barren: the adjectives surrounding the Dungeness landscape are often pejorative in tone. Even the claim that it is so dry as to be a desert triggers the instinctive reaction of a place of death. Yet in its complexity we see a lesson in how we might approach a changing, heating planet, one seen in the lurid orange and red glows of Jarman’s film, or his written accounts of plants burned by salt spray and sun. They’re echoed in his eulogy at the end of The Garden, a reflection on friends lost to AIDS and his own mortality alike: “Old age came quickly for my frosted generation”. I see them too in Peter Marlow’s photograph of overalls drying on the Prospect Cottage washing line, prayer flags for young men departed, lifted on the storm that forever buffets England.

Luke Turner’s book Out of the Woods is published by Orion Publishing Group