In the Studio: Helen Frankenthaler and the Bohemians

Burt Glinn documented the art and workspace of the abstract expressionist painter who was part of Manhattan’s Beat Generation

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member-photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well-known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series here.

Magnum photographer Burt Glinn began covering the movements of the Beat Generation during the late 1950s. The American subculture phenomenon was taking root in the cultural consciousness and it was the time of anti-materialism, anti-capitalism and anti-religion, of sexual liberation and spiritual discovery. This spirit could be found in artists’ studios, at loft parties, in the basement of jazz clubs and in the moonlit parks of Manhattan. It was in the very air, and Glinn, through his tireless documentation, had been seemingly able to bottle it.

Glinn was encouraged by his good friend, and then apartment-mate, Clay Felker who was the editor of Esquire Magazine and later became the founder of New York Magazine. According to Glinn’s widow, Elena Prohaska Glinn, Felker told him to spend his spare time covering ‘the bohemians’, i.e. artists, poets and jazz musicians who created their art right in Manhattan. “As a journalistic photographer, Burt spent months and then several years visiting studios and homes and nightclubs, among them Helen Frankenthaler’s painting studio,” says Prohaska.

Frankenthaler was part of the first generation of abstract expressionist artists, and is widely credited for playing a pivotal role in the development of color field painting. She was born and raised in New York City to a progressive and intellectual Jewish family; her father was the New York State Supreme Court Justice Alfred Frankenthaler, her mother Martha (Lowenstein) Frankenthaler was a German émigré. They supported her artistic education, and she attended the Dalton School under Rufino Tamayo, followed by Bennington College, where she was a student of Paul Feeley.

In 1957, when Glinn photographed her at work in her Manhattan studio, Frankenthaler was only seven years into her professional exhibiting career, which began when Adolph Gottlieb selected her painting Beach (1950) for inclusion in the exhibition titled Fifteen Unknowns: Selected by Artists of the Kootz Gallery. But it was her 1952 painting, Mountains and Sea, which was her true breakthrough. For this work she pioneered the “stain” painting technique, where she poured thinned paint onto unprimed canvas laid on the floor.

She continued to use this process, portrayed in Glinn’s photography, to startling effect, producing paintings with a deft, singular beauty. Frankenthaler once said of her work: “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks labored and overworked, and you can read in it—well, she did this and then she did that, and then she did that—there is something in it that has not got to do with beautiful art to me.”

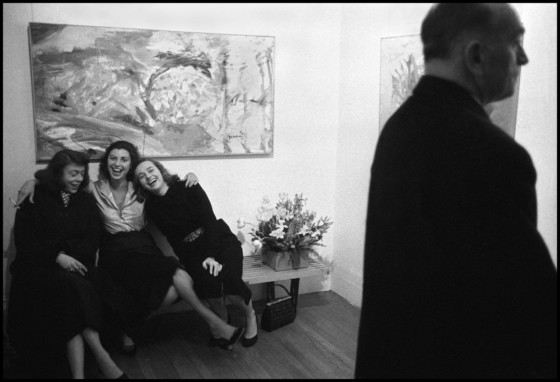

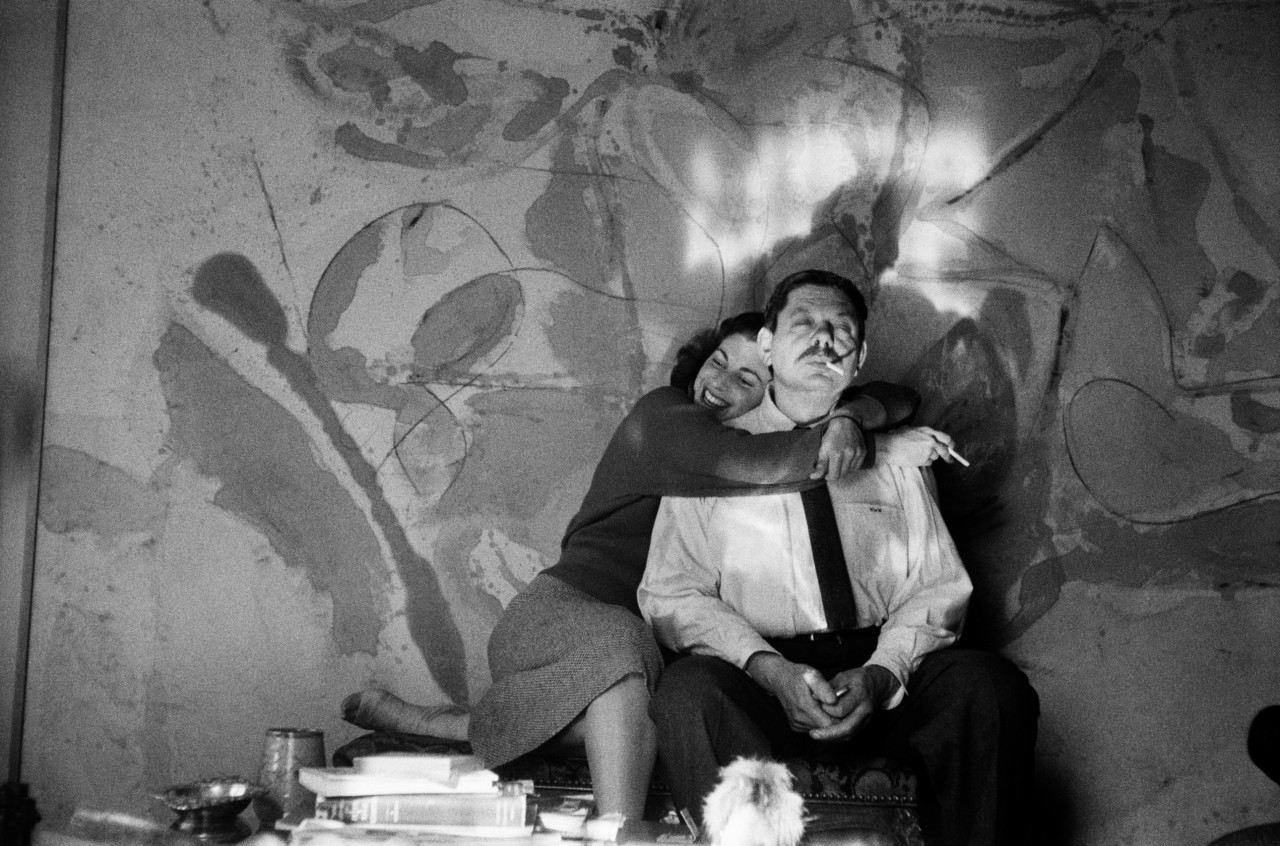

“One of my favorite moments captured by Burt is at the end of the work day, having a drink with the artist and her good friend David Smith and looking at her recent paintings; behind them is Helen’s legendary work of 1952, Mountains and Sea,” recalls Prohaska. “A few weeks later Burt went to the Gallery opening where most of the giants of the New York school of painting were assembled.”