The Mask Series: Inge Morath & Saul Steinberg

Aaron Schuman explores how an encounter between photographer and cartoonist, sparked one of the most singular artistic collaborations in history

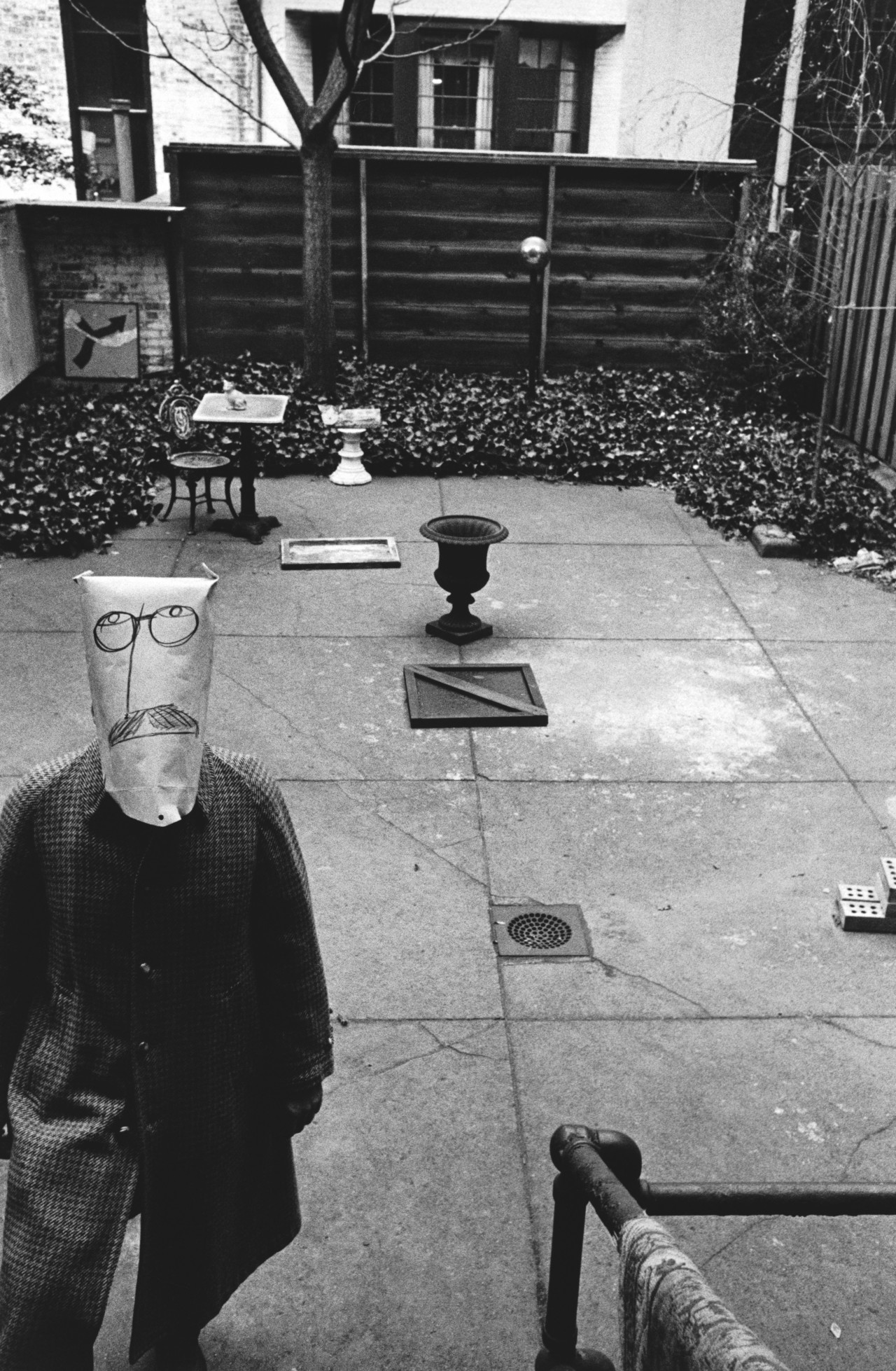

“This is how I remember it…”, the photographer Inge Morath recalled in 2000. “In 1956, I finally got to New York…[Gjon] Mili gave Saul Steinberg a call…and Saul agreed to meet me and maybe pose for a portrait. The date was made. Upper East Side in the Seventies. I rang the bell and Saul Steinberg came out wearing over his head a paper bag on which he had drawn a self-portrait.”*

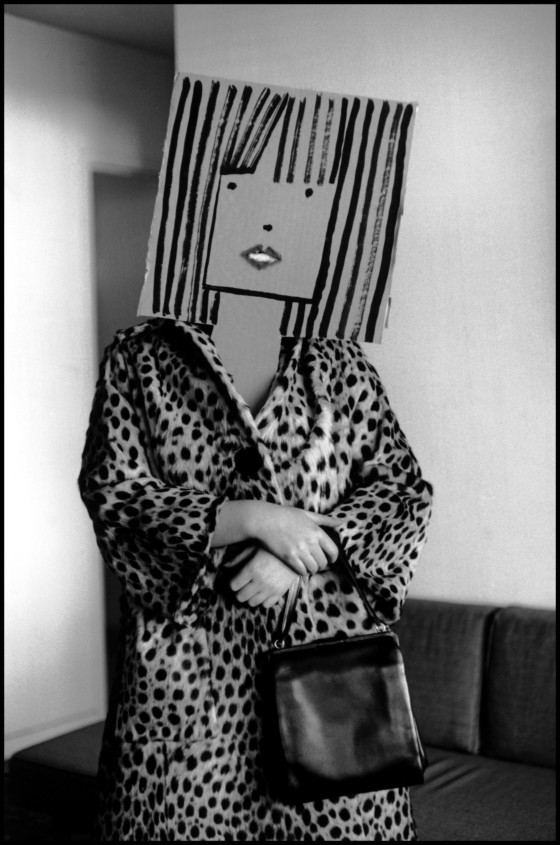

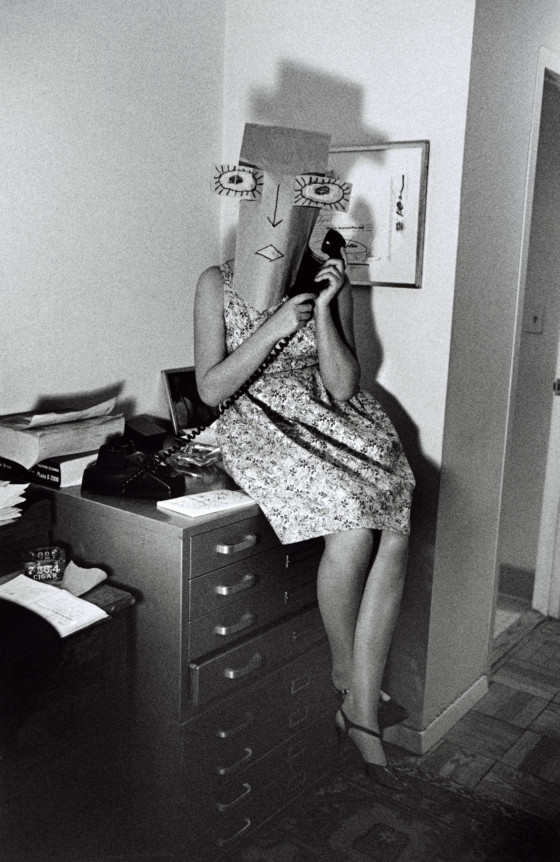

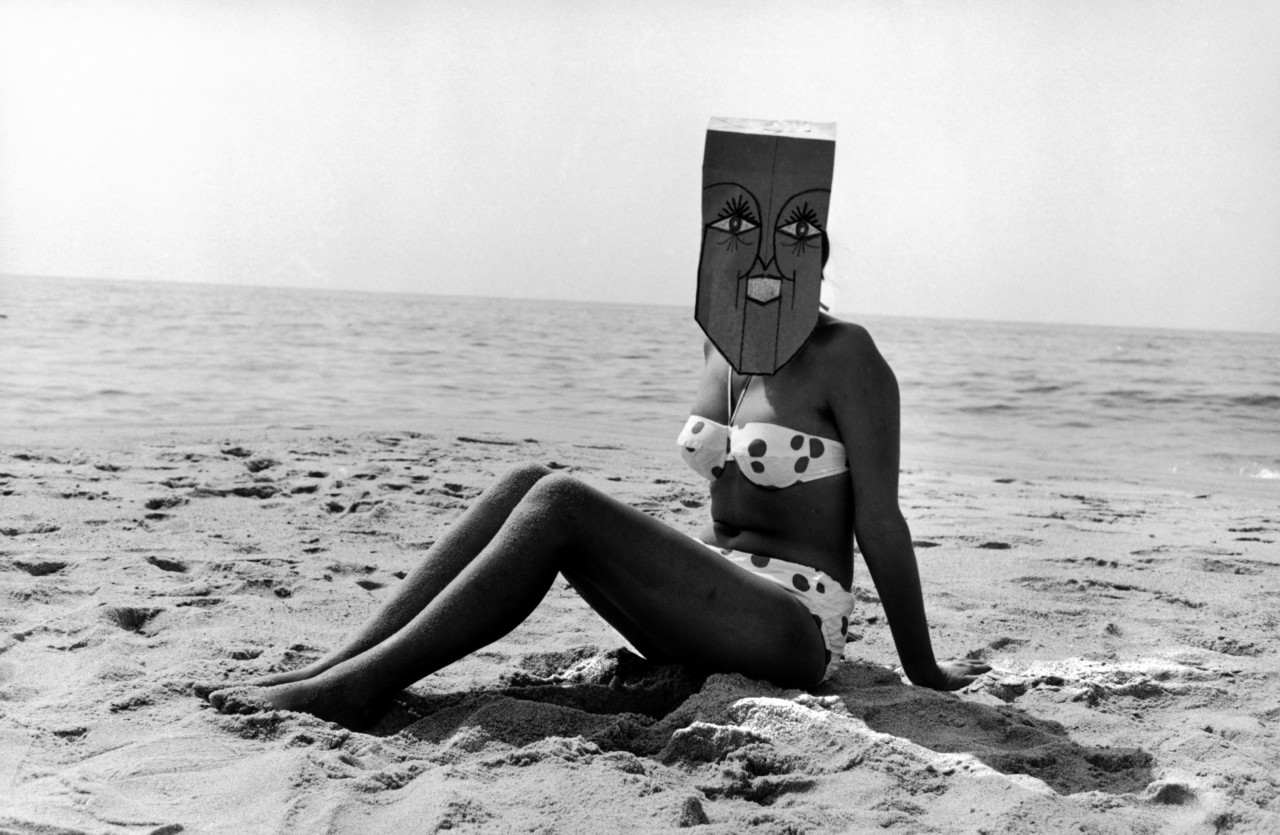

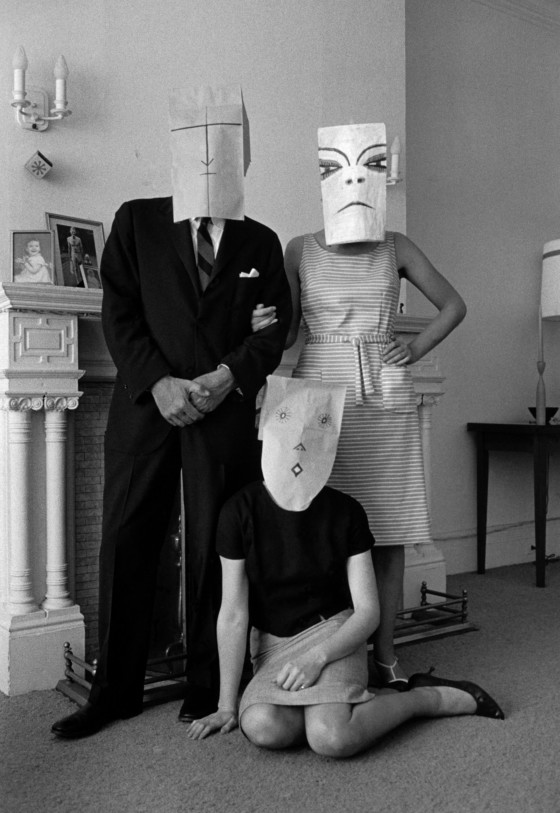

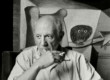

Thus began one of the most quizzical and fascinating artistic collaborations between a photographer and a cartoonist in history. The result – a curious collection of images often referred to as the “Mask Series”, made between their initial meeting and 1962 – portray a range of figures wearing various cardboard box and paper bag masks created by Steinberg, photographed in a rather straightforward and unpretentious manner by Morath.

At first glance, these pictures do not entirely resemble those in Morath’s more traditional photojournalistic oeuvre, which often took its lead from the spirit of the ‘decisive moment’ and relied on quick-witted spontaneity and insightfully whimsical observation. Instead, they tend to suggest a more experimentally inspired combination of early twentieth-century Modernism (i.e. Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon – 1907), Henri Cartier-Bresson’s semi-casual portraits of revered artists, writers and philosophers (i.e. Henri Matisse, Albert Camus, Igor Stravinsky, Jean Paul Sartre, and the like – 1940s), and the cool heights of New York’s mid-century intelligentsia (i.e. Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s – 1958).

Yet, given the journeys of the two artists involved, such an intriguing confluence of avant-garde cultural reference points from the previous fifty years, and from both sides of the Atlantic, was by no means a strange coincidence.

"Thus began one of the most quizzical and fascinating artistic collaborations between a photographer and a cartoonist in history"

- Aaron Schuman

Born in Austria in 1923, Inge Morath spent her teenage years in pre-war Berlin, and then studied languages at the University of Berlin throughout the Second World War, eventually becoming fluent in French, English, Romanian, Spanish, Russian and Chinese, as well as in her native German.

After the war, she initially worked as a translator for occupying Americans, and then as a journalist throughout Europe. Robert Capa – impressed by her writing for Heute, a magazine published in German by Information Services Branch of the US Army in Occupied Germany – invited her to work as an editor in Magnum’s office in Paris in 1949. There she quickly encountered contact-sheets sent in by Cartier-Bresson, stating years later, “In studying [Henri’s] way of photographing I learned how to photograph myself, before I ever took a camera into my hand.”† By the early-50s, Morath had become a successful photographer in her own right, and was invited to join Magnum as such in 1953, spending the following decade travelling the world and publishing photo-essays in magazines such as Holiday, Paris Match, Vogue, and more.

Born in Romania nine years before Morath, Saul Steinberg enrolled to study architecture at the Polytechnic University of Milan, which he once described as “a comfortable school…under the influence of Cubism”‡. As a student there he began to contribute cartoons to Bertoldo – a Milan-based humour magazine with a satirically surreal slant – before fleeing from the rise of Fascism and anti-Semitism in Europe, and eventually moving to New York in 1942, where he found regular work as a cartoonist and illustrator for The New Yorker, amongst other publications.

In 1946, he was invited to participate in the “Fourteen Americans” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and by the mid-1950s, Steinberg had established himself firmly within Manhattan’s literary and artistic scenes, exhibiting regularly at galleries and museums worldwide, and frequently contributing not only to The New Yorker, but also to Vogue, Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, Fortune, TIME and LIFE.

"In studying [Henri’s] way of photographing I learned how to photograph myself"

- Inge Morath

Aesthetically, conceptually, tonally, and otherwise, the “Mask Series” is derived from the exceptional lives of its creators, and is the result of a collision between two dynamically experienced Europeans in the heart of uptown Manhattan during America’s liveliest boom-years. As such, it offers both a uniquely sophisticated and subtly sardonic, tongue-in-cheek perspective on this particular place at this particularly peculiar time.

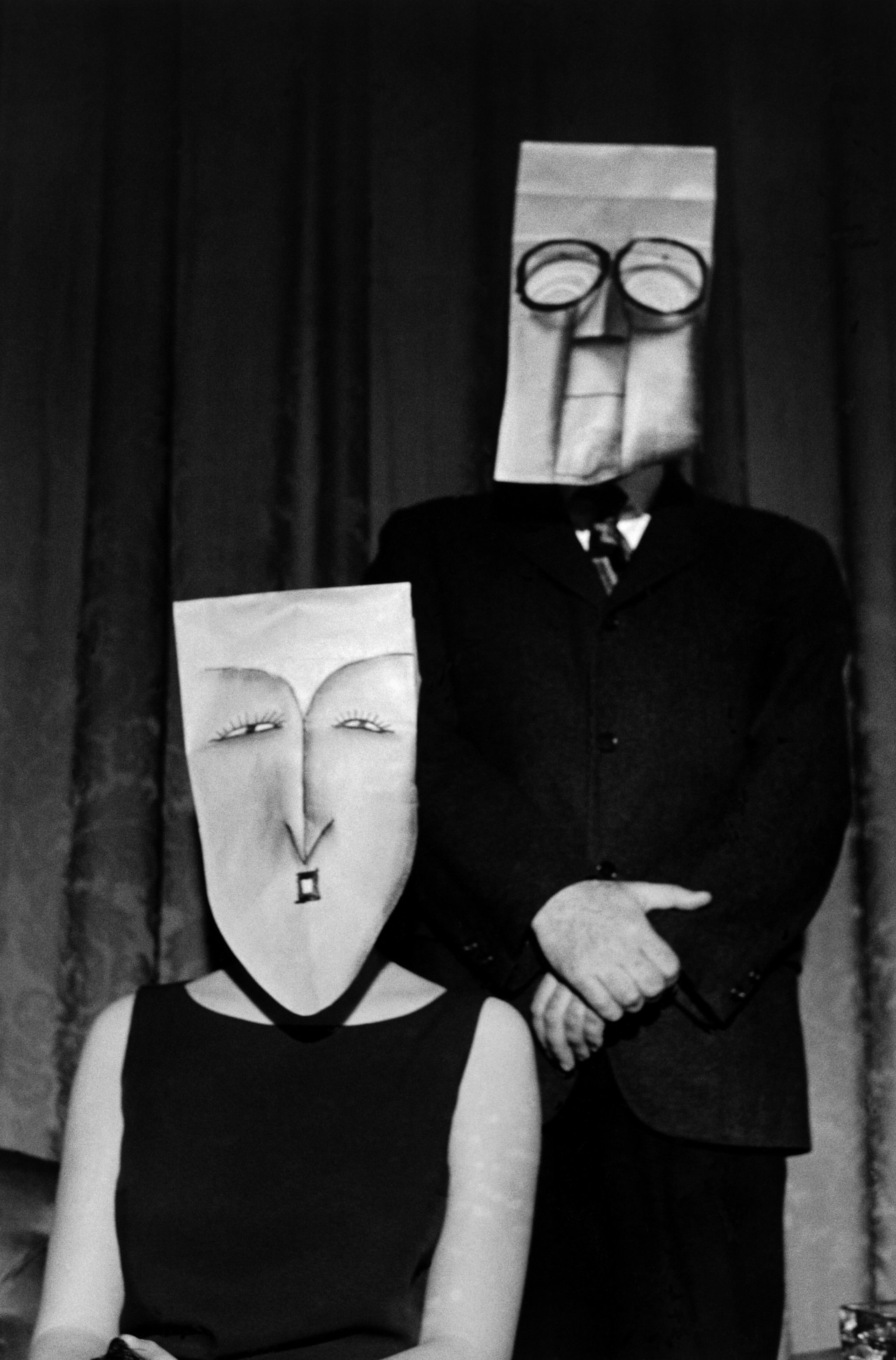

The earliest pictures begin with Steinberg in his own apartment, simply modeling masks that reflect variations of his own alter-ego; a remarkably consistent long-faced, bespectacled middle-aged man, plainly drawn with a wide moustache and a perpetual deadpan expression (rendered as simply as possible; a single, straight, perfectly horizontal line for a mouth). But gradually, as Steinberg’s masks developed and evolved over the years – from plain self-portraits into a variety of elegant, elaborate bug-eyed creatures who often sport unsettlingly manic smiles, or alternatively into a medley of heavy-browed, heavily-shadowed sculptural characters who seem to exude a rich and rather world-weary interior world – Morath’s photographs also become more dynamic and improvisational. She gradually begins to recruit “friends, a couple of young women in my office, and several wayward poets”§ and asks them to pose for her whilst wearing Steinberg’s masks; additionally, she finds new locations in which to set them, including an elegant Gramercy Park townhouse, rooms at the Chelsea Hotel, Long Island beaches and beach-houses, and elsewhere.

On their surface, these images appear playfully performative, joyful, and imbued with child-like humour and imagination. Yet looking at the series more closely and collectively, the photographs gradually begin to act as cryptic metaphors for the eerie cheeriness and forced innocence of 1950s post-war America, as seen through the eyes of two world-weary Europeans who were more than wary of a culture that masked its underlying turmoil in syrupy self-satisfied grins, and buried its insecurities underneath superficial displays of prosperity and grandeur.

Steinberg’s evolving masks, as well as a Morath’s variety of carefully chosen moments, locations, and choreographed “casual” poses, transform their subjects into caricatures of the time – high-society ladies in fur coats and little black dresses; smart-aleck secretaries; self-satisfied businessmen; bathing beauties and batty bohemians. Simultaneously, by hiding the identity of their subjects behind these whimsical facades, they both reveal and exaggerate the sickly, sinister nature of the 1950s American Dream as it was peddled by the “Mad[ison Avenue] Men” only blocks for Steinberg’s flat, and performed by the country at large. Set within the quaint cosmopolitan comfort of New York sophistication, these grimacing figures distort and subvert the smugness of the era, in a sense anticipating the cutting street-photography that would define the same city during the following decade – think of the real-life “masks” revealed in Diane Arbus’s Two Ladies at the Automat, Woman With a Veil, Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park and so on, or those worn by the figures marching up and down Fifth Avenue in the work of Garry Winogrand.

"These grimacing figures distort and subvert the smugness of the era"

- Aaron Schuman

Most of us are familiar with the Hollywood version of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and its now-idolized protagonist, Holly Golightly – the happy-go-lucky “New York darling”, who, draped in Givenchy, casually eats breakfast (out of a paper bag) while admiring the window displays at Tiffany & Co., and hosts fabulous cocktail parties at her small, walk-up apartment (Upper East Side in the Seventies) late into the night. But the 1961 film starring Audrey Hepburn (whom Morath photographed on the set of The Unforgiven in 1959 – coincidentally one of the most prolific years in terms of her collaboration with Steinberg as well), only hints at the underlying chaos behind Golightly’s carefree demeanour, and ultimately ends “happily ever after”.

Yet Truman Capote’s original 1958 novella tells a very different story – of a teenage runaway from Texas, who lost her parents as a child, survived an abusive foster family alongside her brother, was forcibly married at the age of fourteen to a much older man, escaped to the big city, and survives by running favors for the mob and indulging the aggressive and at times violent behavior of rich, manipulative men in return for expensive presents and the hope that eventually one of them will take care of her.

Like the “Mask Series”, Capote’s version seduces us with the most charming of facades, only then to slowly reveal the true sadness hidden behind it, and the desperate reality of this uniquely American Dream. Unlike the film, the book actually opens twelve years after Golightly has skipped bail and disappeared entirely, when its narrator is handed a manila envelope containing several images – in fact, pictures of an African mask:

“In the envelope were three photographs more or less the same, taken from different angles; …an odd wood sculpture, an elongated carving of a head, a girl’s, her hair sleek and short as a young man’s, her smooth wood eyes too large and tilted in the tapering face, her mouth wide, overdrawn, not unlike clowning lips. On a glance, it resembled most primitive carving; and then it didn’t for here was the spit-image of Holly Golightly, at least as much of a likeness as a dark still thing could be.”ǁ

A new illustrated biography of Inge Morath, by Gordon Linda will be released in October, 2018, published by Prestel. More information on the release here.

* Inge Morath, Saul Steinberg: Masquerade (New York: Viking, 2000), pp. 3-7.

† Inge Morath, I Trust My Eyes (Manuscript for Berlin Lecture) (Inge Morath Estate: unpublished, 1994),

p.15.

‡ Saul Steinberg, “Chronology,” in Saul Steinberg [Exhibition Catalogue] (New York: Whitney Museum of

American Art, 1978) p. 235.

§ Inge Morath, Saul Steinberg: Masquerade (New York: Viking, 2000), p. 15.

ǁ Truman Capote, Breakfast at Tiffany’s (London: Penguin Books, 2000) , p. 12.