What Makes a Museum?

We look over Magnum photos made at New York's Museum of Modern Art spanning more than seven decades

A number of images from this article are available as part of the newly expanded New York Collection of Fine Prints on the Magnum Shop.

Museums are, for some, the dusty hallways of drawn-out school visits: the sombre halls walked by the cultural elite. They are the place to preciously guard masters and their ideas, or at times to preserve colonial loot. Museums represent established culture and legitimize movements; but they are also the place collective memories and meanings are made and tenderly held – where lives and histories intertwine, begin and end.

Since it first opened its doors on Fifth Avenue in November 1929, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, has been something of an experiment – sometimes because there was no choice. Indeed, the museum was unveiled just over a week after the Wall Street Crash. Alfred H Barr Jr. referred to it as “a laboratory,” in 1939—one that the public could participate in. A lot is made of the works that hang in a museum – but what of the museum, its architecture, spaces and the visitors who activate it, day after day, year after year?

"It’s these kinds of interactions, between past and present, inanimate and animate, that remind us of the role of a museum in reflecting and reaffirming life"

-

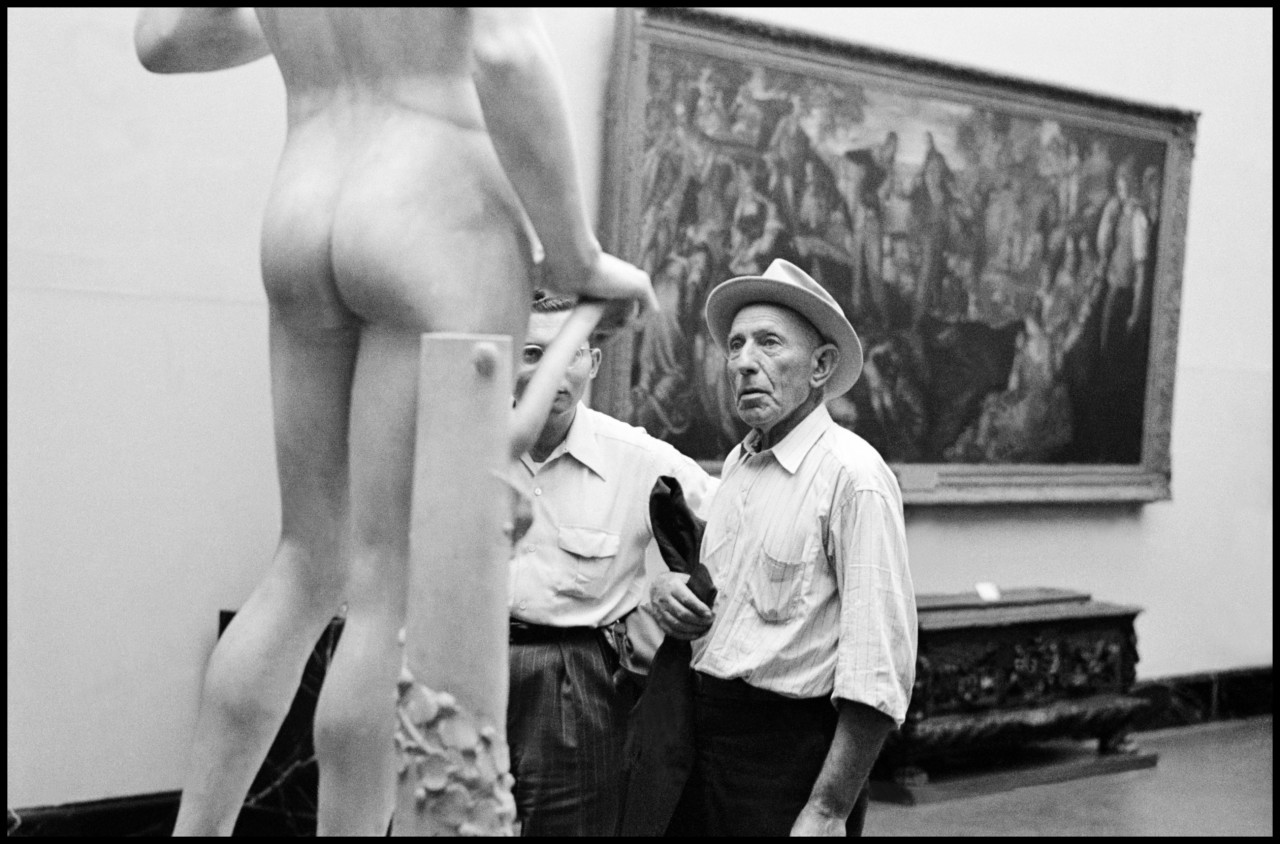

Burt Glinn’s 1949 photograph – taken before Glinn became one of the first American photographers to join Magnum, in 1954 — of two male visitors staring with bemusement at the intimate parts of a nude male sculpture give a playful glimpse into the museum experience. Clearly amused by their reaction to the art, Glinn also identifies one of the many unique opportunities that modern art presents; to bring us close-up, face-to-face with the unexpected.

"A lot is made of the works that hang in a museum – but what of the museum, its architecture, spaces and the visitors who activate it...?"

-

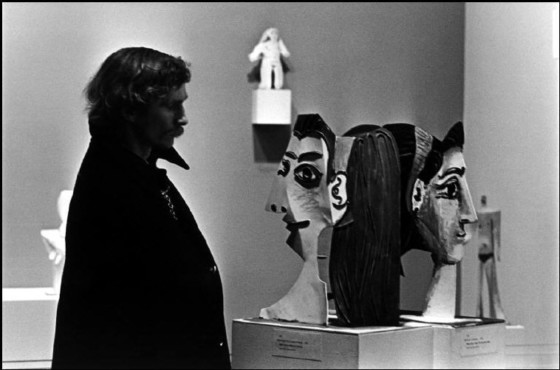

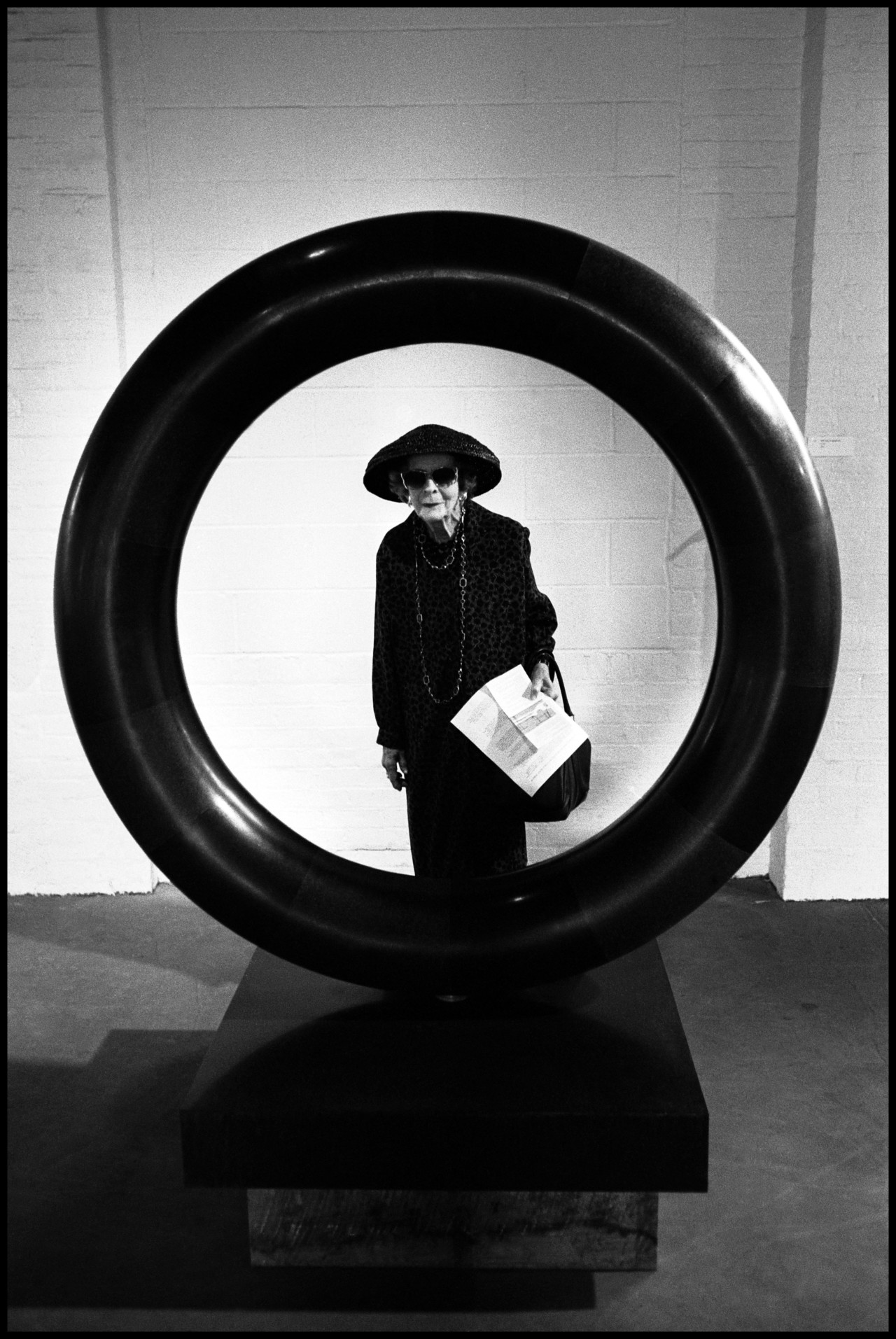

Eve Arnold – who also joined Magnum in 1954 – likewise captures the MoMA viewing experience with candor, through intimate, voyeur-like snapshots of solitary guests as they look at the art. She finds delightful juxtapositions between the spectator and the art: the elegant chignon of the Italian actress Slyvana Mangano and the low pile of hair twisted into a knot of a bust she gazes towards; a chic, gloved visitor in 1959 looks down over her glasses at a tiny sculpted man with an ample paunch, as if they’re locked in some kind of face-off, both equally unimpressed. It’s these kinds of interactions, between past and present, inanimate and animate, that remind us of the role of a museum in reflecting and reaffirming life.

"The relationship between MoMA and its public is unique. An architectural and cultural landmark in Manhattan, it has been the place in which much of the city’s own art history has been made"

-

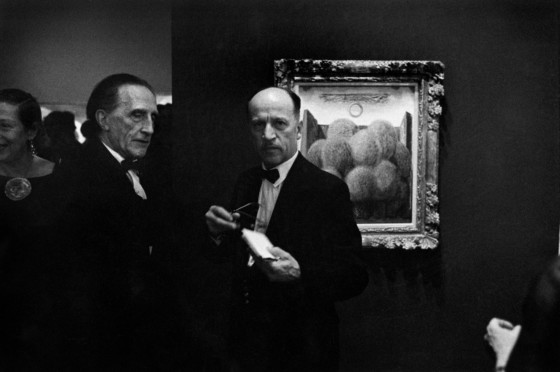

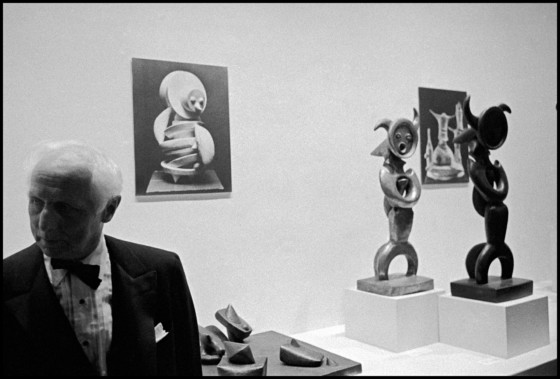

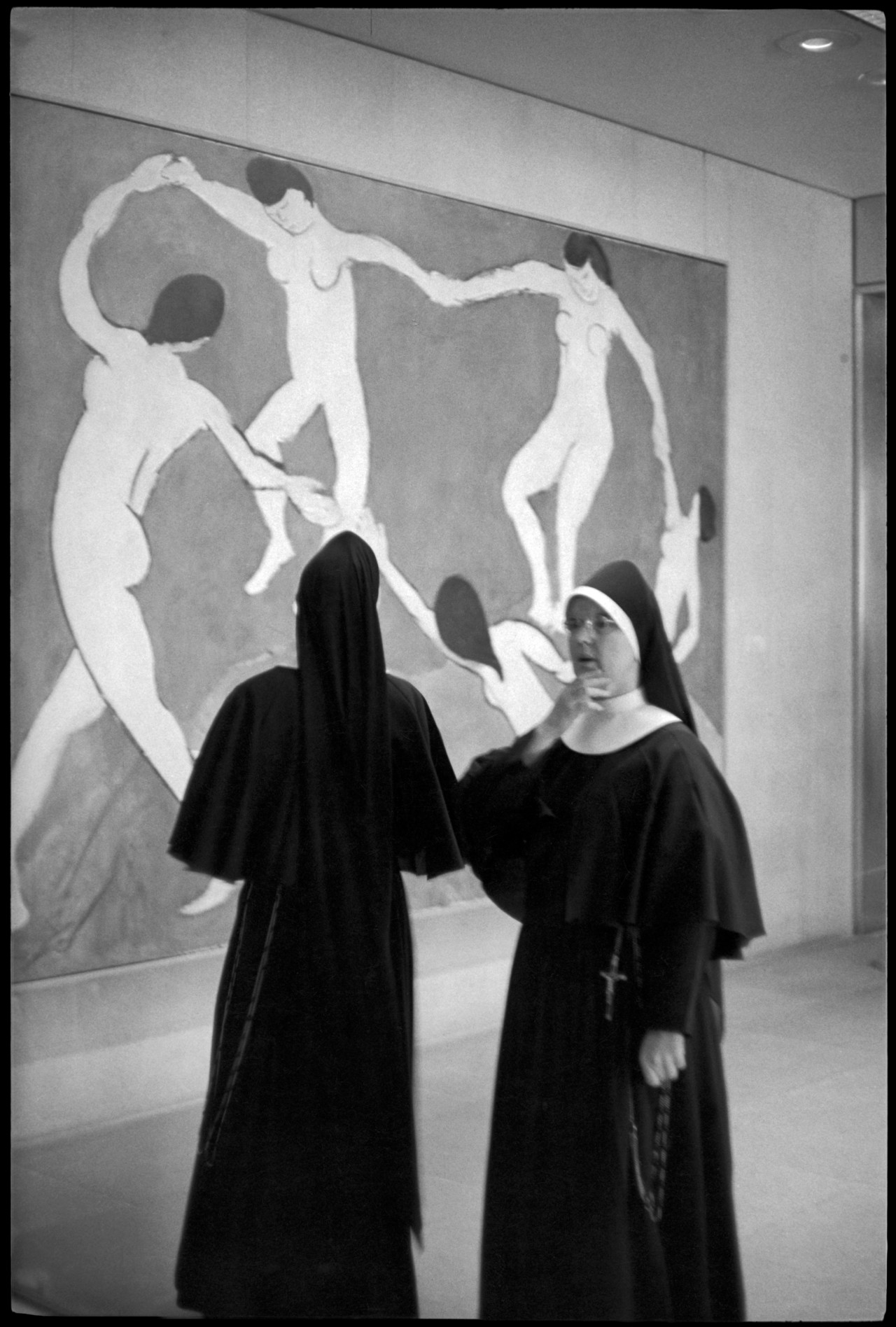

The relationship between MoMA and its public is unique. An architectural and cultural landmark in Manhattan, it has been the place in which much of the city’s own art history has been made. Henri Cartier-Bresson documents one of the many monumental occasions at the museum, with pictures of the opening of the historic 1939 retrospective of Picasso’s work – a show that defined the artist and the museum for decades after, while Matisse’s La Danse appears behind two nuns in deep discussion in another of his unforgettable MoMA pictures. Masterpieces are just visible behind glamorous guests in Dennis Stock’s candid shot of a suited Marcel Duchamp at the opening of Max Ernst’s retrospective in 1961. Decades later and Martin Parr photographs the queues for a Bonnard exhibition, a younger, more casually dressed audience, sheltering under the coats from the rain. Style may have changed, but with drinks in hand and silly poses in front of the art – it seems that habits haven’t much.

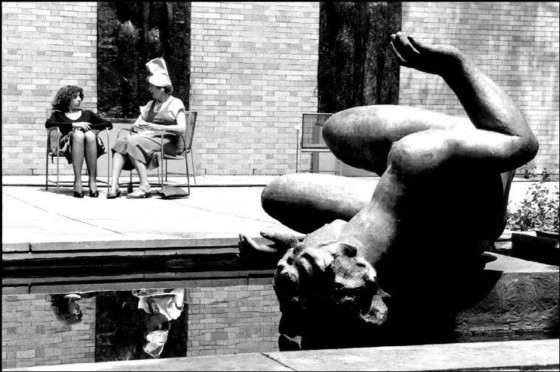

Museums are made by the people who inhabit them – and the people who create the works. Other historic moments in MoMA’s history are recorded by Wayne Miller, in a photograph of the shuffling crowds at a rare early photo-exhibition, in 1955, Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man (which Miller co-curated); in another Cartier-Bresson image a young couple take a break at the café; while René Burri trains his lens on two women chatting in the garden. These images present the museum not only as a cultural institute but as a place where all kinds of people come together – a place where time is seemingly suspended.

"Museums are made by the people who inhabit them"

-

Until somewhat recently, with some notable exceptions, photographers have mostly been onlookers at museums. Little space existed for photography as an oeuvre in the world’s artistic institutions. MoMA was one of the first to acquire and exhibit photographs, and its photography department was established as far back as 1940, eleven years after its founding. The first photographs were acquired by the museum in 1933, from Walker Evans’ solo exhibition, Photographs of 19th Century Houses. That was the first solo exhibition on photography to take place at MoMA. Erich Hartmann captured another piece of photography’s history at MoMA, in a portrait of the late Curator of Photography, Grace M. Mayer, who joined the museum in 1958 and organised the first exhibitions in the museum’s dedicated photography galleries, opened in 1964.

"There are also those moments when a museum is empty – standing still and monumental..."

-

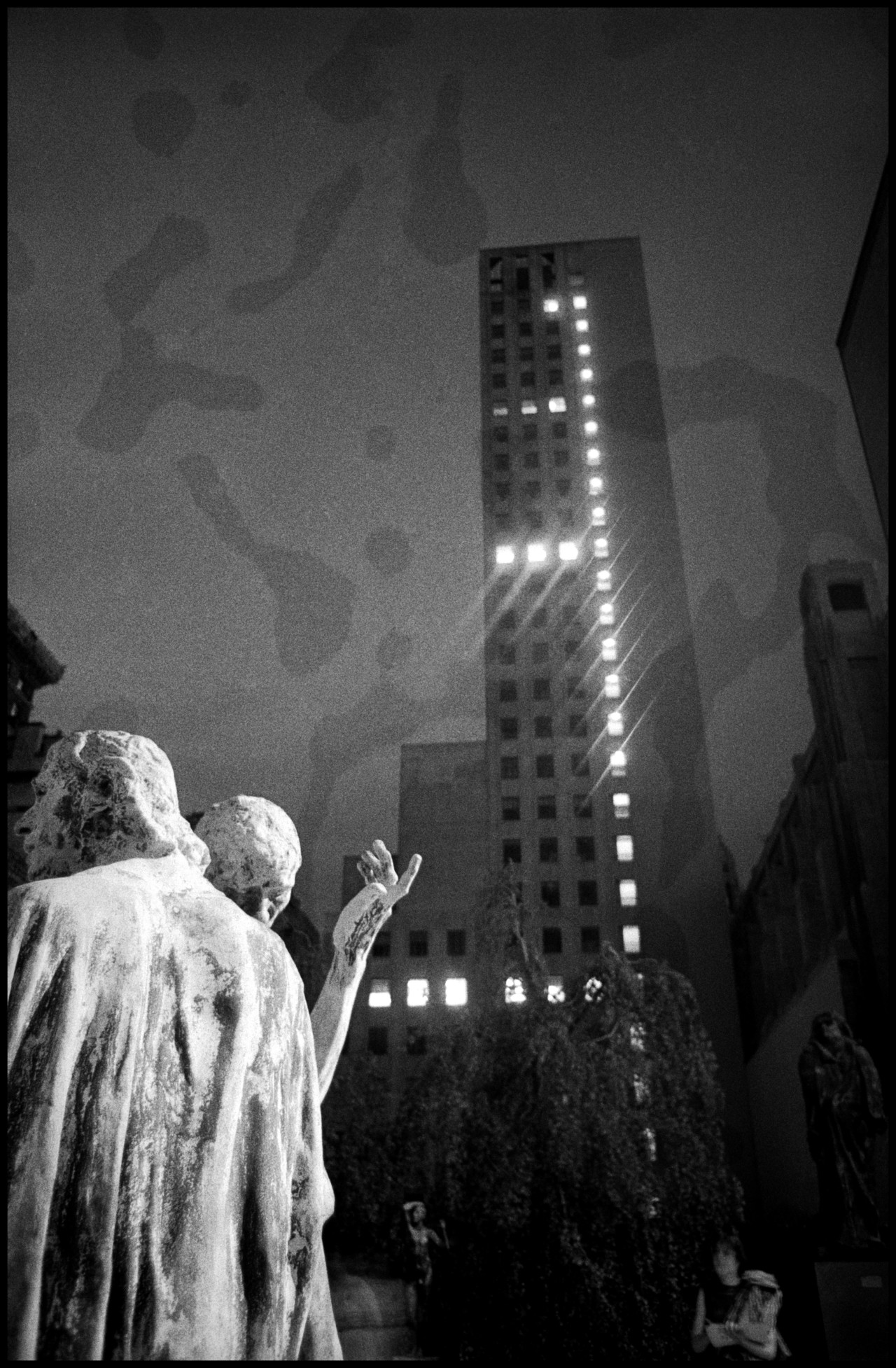

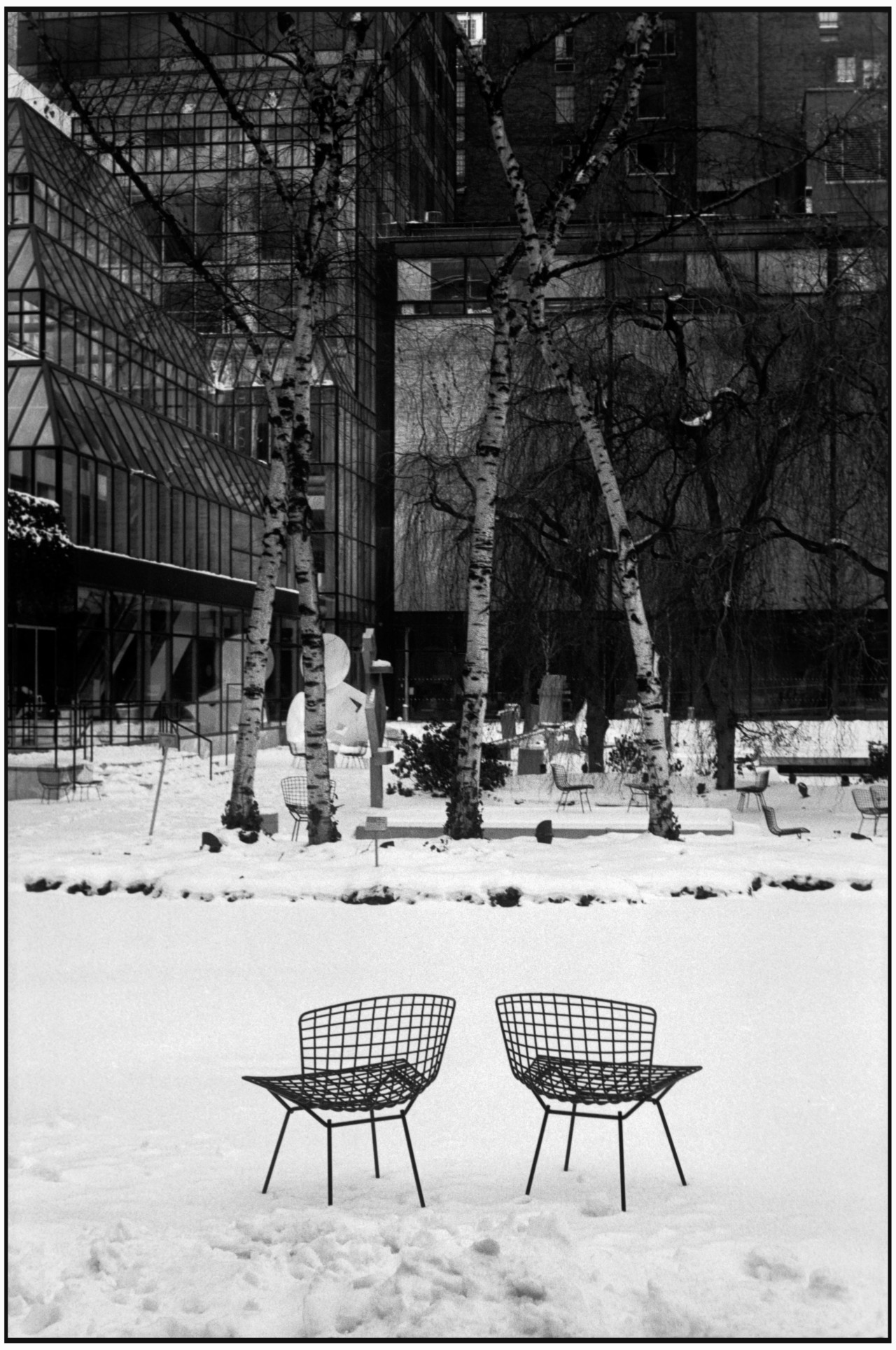

There are also those moments when a museum is empty – standing still and monumental. Architectural megaliths that have been transformed multiple times, museums become an intrinsic part of the cityscape.

Other images offer more architectural views of MoMA over the seasons and years, taken from a distance, and revealing the museum’s DNA, documents of its structure and essence – either before the masses descend or as they teem through it. An image by Richard Kalvar sees sculptures by Alberto Giacometti – instantly identifiable – aping the high-rise structures of Lower Manhattan.

The world has seen seismic social and political shifts over the ninety years of MoMA’s existence, and as it prepares for its latest incarnation it is also preparing to evolve, to better represent the world as it is now and redress the imbalances of the past. Micha Bar-Am’s fallen statue offers a metaphorical hint at the new order taking over, a reinvention of history as we know it, and a reminder that the structures of a museum sometimes need to be dismantled and rebuilt.