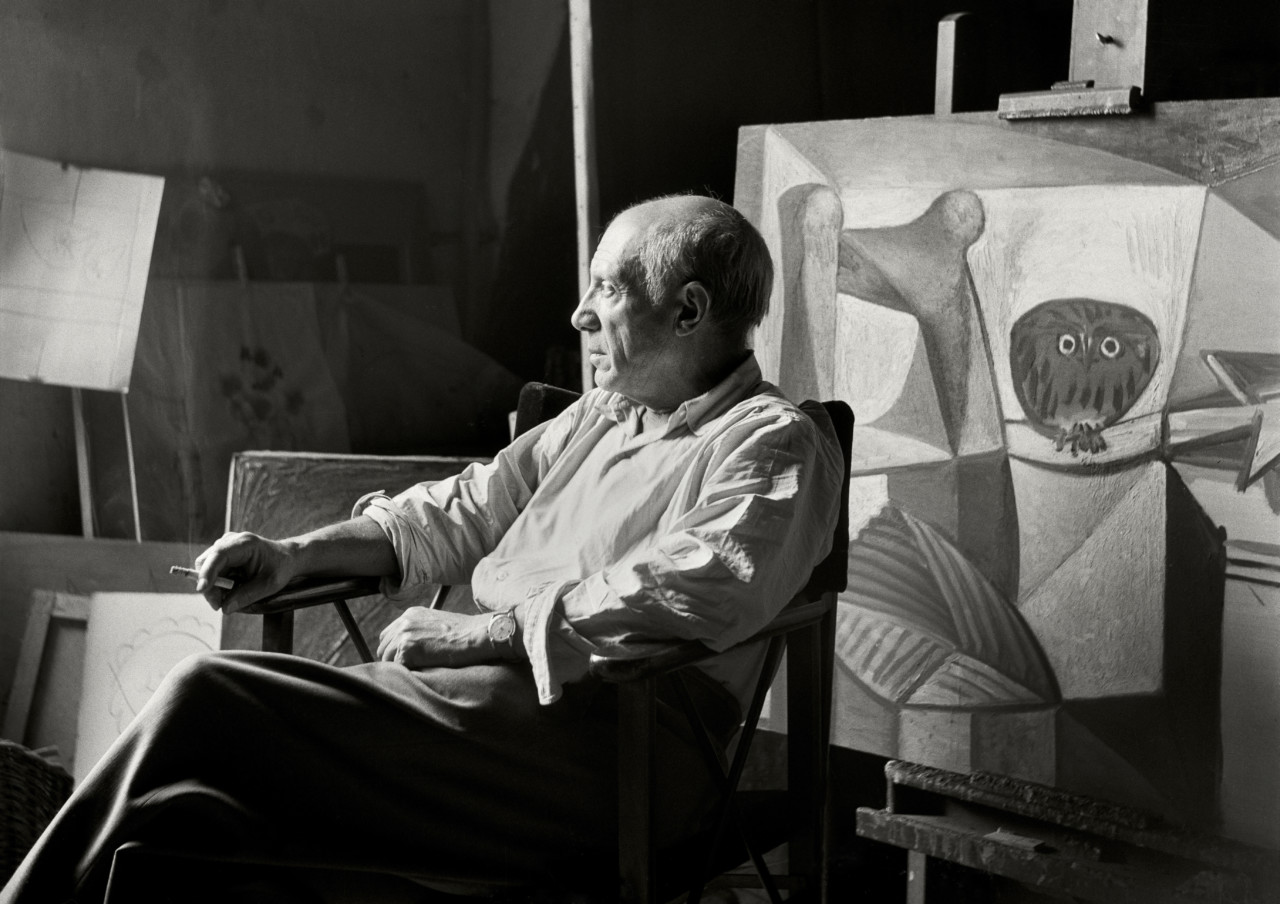

Photographing Picasso

Charlotte Jansen reflects on how the camera worked to serve the artist’s mythos

Magnum Photographers

By the time of his death in France in 1973, Pablo Picasso’s place in history was cemented, but his journey to becoming the 20th century’s most famous artist was not only achieved with his paintings—as the “most photographed artist in history,” the ‘Picasso myth’ was created with the camera, capturing contemporary imaginations, and still fascinating today.

"Photography was also a way for him to document his artworks, to experiment with new ideas"

- Charlotte Jansen

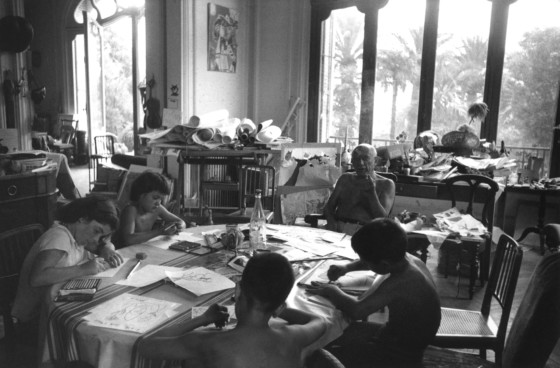

Though explored less than his other works, Picasso was equally interested in getting behind the lens as in front of it—as his friend and biographer, John Richardson, revealed in Picasso and the Camera, the artist owned many cameras, “mostly Leicas”, and used them extensively in his own practice. As cameras became smaller, more portable and accessible, Picasso began to introduce them to his studio practice: he used photographs for references for paintings and sculptures, photographing things that inspired him inside and outside the studio, from lovers to landscapes. Photography was also a way for him to document his artworks, to experiment with new ideas. Richardson also highlighted the importance of source photographs in Picasso’s sculpture, such as a book on ancient Greek sculptures published by Christian Zervos.

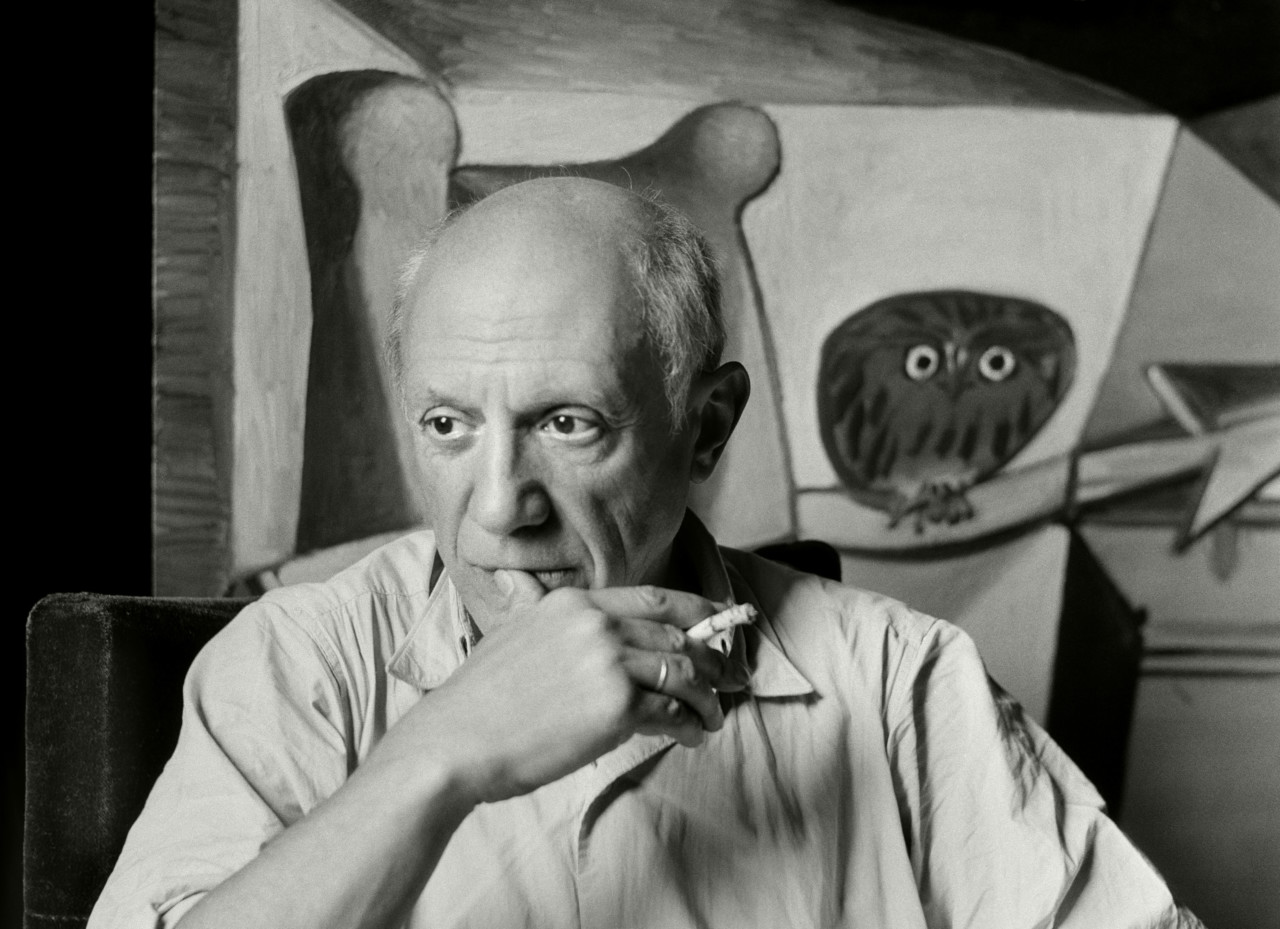

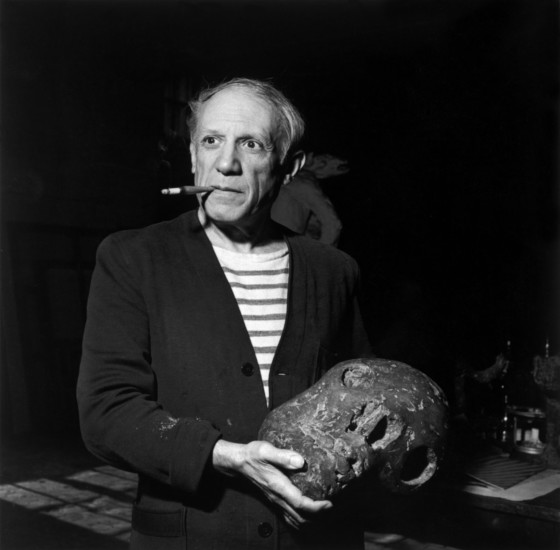

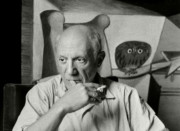

In the mid-twentieth century, as photography became a mass media, Picasso was quick to harness the power of a picture. After the Second World War, as photojournalism became more sophisticated at storytelling, and began to pervade personal and private lives, Picasso befriended photographers who frequently took his portrait: among them Brassai, Man Ray, Cecil Beaton, and Magnum co-founder Robert Capa. They helped disseminate images of a virile, red-blooded, cigar-smoking raconteur and dandy, ruggedly handsome, who married twice, fathered four children by three women and had countless attractive lovers—all part of the narrative that would propel Picasso into prosperity.

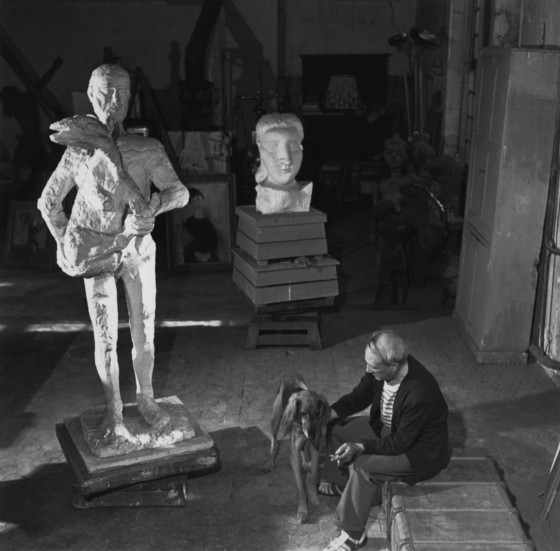

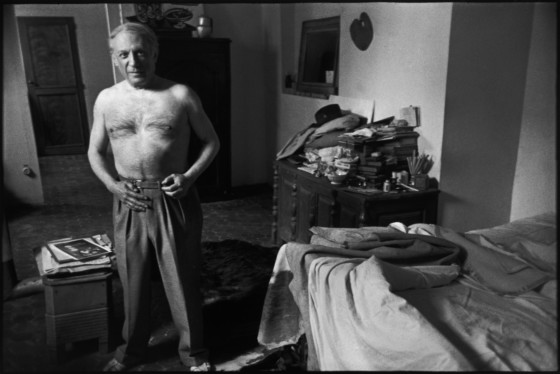

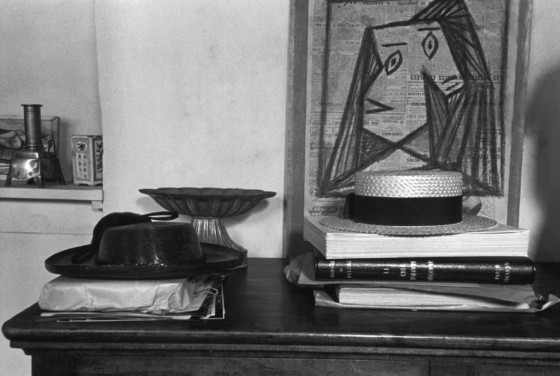

Pictures of Picasso’s studio on Rue des Grands by Magnum photographers Herbert List and Robert Capa gave some of the first glimpses into the artist’s working environment, and an insight into his practice at the time; sculptures and assemblages hinting at how he approached building shapes and narratives into his painting. Later, Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson captured Picasso’s home, an apartment on Rue des Grands-Augustins: in one particularly intimate picture, taken in 1944, Picasso stands in his bedroom, bed unkempt, bare-chested, hands on his belt in a gesture that is both seductive and vulnerable.

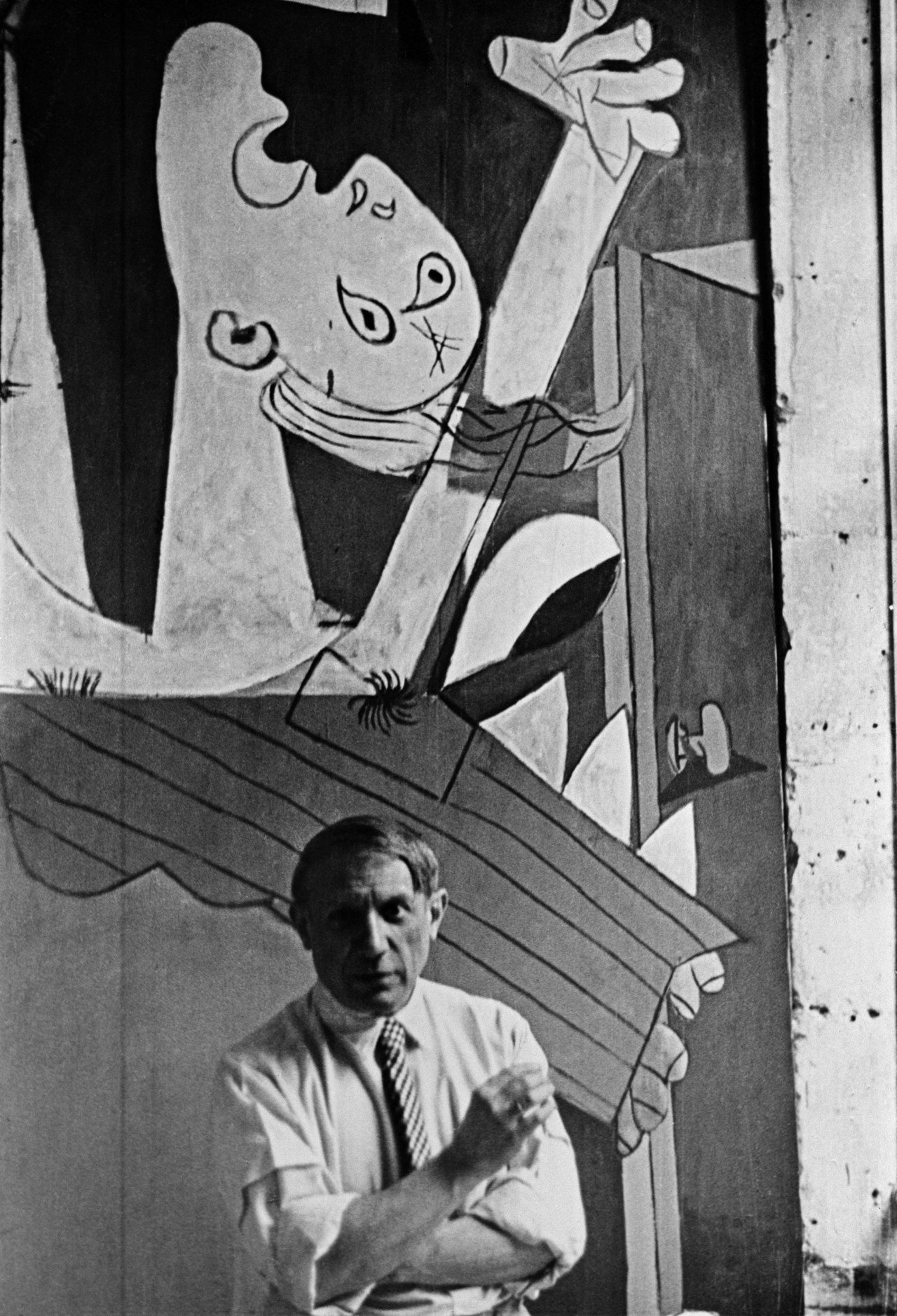

The role of the Magnum photographers in creating the Picasso myth was decisive. In 1937, a year into the Spanish Civil War, David Seymour captured the painter in front of his vast, iconic work Guernica—painted in rapid response at Rue des Grands-Augustins, displayed just six weeks after the bombing of the Spanish village.

"In the mid-twentieth century, as photography became a mass media, Picasso was quick to harness the power of a picture"

- Charlotte Jansen

It is Guernica that connects Picasso to Robert Capa. Though 32 years Picasso’s junior, the two had much in common: both were immigrants, both fled the Nazis, and sympathised politically with the left (and were associated with Communist parties) and both were indefatigable in their chosen art forms, creating prolifically in their lifetimes—40 short years for Capa, 91 for Picasso.

From 1936 to 1939, Capa was also in Spain to document the Civil War, and, like Picasso, it was the war that would inspire his most famous works—‘The Falling Solider’ (1936) the photograph for which Picture Post called Capa “the world’s greatest war photographer”.

"Capa shows us Picasso not as a great artist, but simply as a man."

- Charlotte Jansen

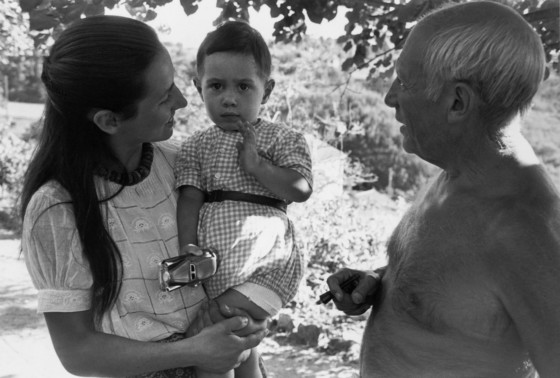

While on assignment in the South of France in the summer of 1948, Capa, who had met Picasso’s partner Francoise Gilot in Paris in 1945, spent time with the couple and their children on the Cote D’Azur. “Capa was a friend, so it was not formal at all.” Gilot said of the photographs Capa took of them at the time—Picasso playing in the sand on the beach with his son, dutifully carrying a shade over Gilot’s head, a side of the artist that had seldom been seen. The tender portraits caught up-close by Capa show Picasso as a barefoot, footloose father, enjoying life’s simple pleasures. Capa shows us Picasso not as a great artist, but simply as a man. They remain among the most memorable pictures of Picasso, and part of the myth that persists today.

Whether the pictures present us with the ‘real’ Picasso, we will never know, but as Picasso himself said, “we all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.”