As it may be

Bieke Depoorter’s book captures the transient yet powerful moments of fleeting interactions

Since 2011, during several key moments in the uprising, Bieke Depoorter has travelled to Egypt regularly, attempting to find trust in times of turmoil and suspicion, where private life is often shielded. She asked people she met by chance if she could spend the night at their homes. Women, their husbands and children shared their daily life, their food and even their beds with her. This personal engagement is at the core of Depoorter’s practice. In 2017, she revisited the country with her work and invited others to contribute by writing comments directly onto photographs. Contrasting views on country, religion, society and photography arose between people who would otherwise never cross paths. As it may be is Depoorter’s depiction of a population navigating transition with integrity, commitment, and respect.

The following is an excerpt from the book’s text by writer Ruth Vandewalle.

“A boy is hiding behind the yellow door on which he tried out his first letters a few summers ago. On the bench, his grandmother is dozing away the day. With her old hands, she tries to dim the light. In the room, time is standing still—only the poster of a president on the wall reveals which year this could be. This intimate tableau is timeless, as if nothing ever changes within the walls of this house. It seems to exist in a vacuum, a free haven, where time, space, and the outside world do not apply.

The fragile vacuum implodes when the television switches from a Bollywood series to a news program.

The square is being evacuated. Two young soldiers are dragging a young woman’s body along the ground. Her long black abaya comes loose, her abdomen exposed. She is wearing blue jeans and a blue bra. She seems to be unconscious. A third soldier stomps on her, the sole of his army-issued boots hitting her bared torso. The camera cannot register the sound of her breastbone cracking.”

"The camera cannot register the sound of her breastbone cracking."

- Ruth Vandewalle

“It is December 2011 when Bieke Depoorter travels to Egypt for the first time, on an assignment for the Belgian photo project Cairopolis. Tahrir Square is heaving once again. The revolution that began on January 25 is ongoing. President Hosni Mubarak has been driven out by his own people after three decades of autocratic power. Once the epicenter of the revolt, the square remains a camping ground for revolutionaries and Egyptians who want to bring about change in their country.

Bieke prefers to explore quieter places, away from Tahrir Square and its uprisings. Wandering across the country, she gravitates toward the unseen side of the revolution. People are friendly, but Bieke senses how the private sphere is protected, out of bounds; how difficult it is to gain trust, to be allowed to enter. But this difficulty intrigues Bieke. Her quest to establish relations of mutual trust sets her on the path of what is to be a long journey.

In the six years that follow, Egypt is locked in political turmoil. However, in a country inhabited by more than ninety million people, life is lived between extremes. Reality is kaleidoscopic: fragmented, often opposing realities that coexist. The political earthquakes are tangible and are continually being broadcast in news reports and analyses. Changes in everyday life, in the thoughts and dreams of the people, are more subtle and often hard to grasp. When Bieke is traveling in a crowded microbus, the big changes fade into the background. She takes us with her to visit ordinary living rooms. Her images become an antidote to the uniform images repeated in the media, which prefers to cover conflicts or subjects that are more extraordinary or unfamiliar. Her pictures, however, inspire recognition, suggesting we are more alike than we would suspect.”

“They prefer to have pictures taken not in their homes, but in a photography studio. That’s where eyes are colored blue, castles and sunsets are pasted in, and red hearts are Photoshopped on top: ‘Together forever’.

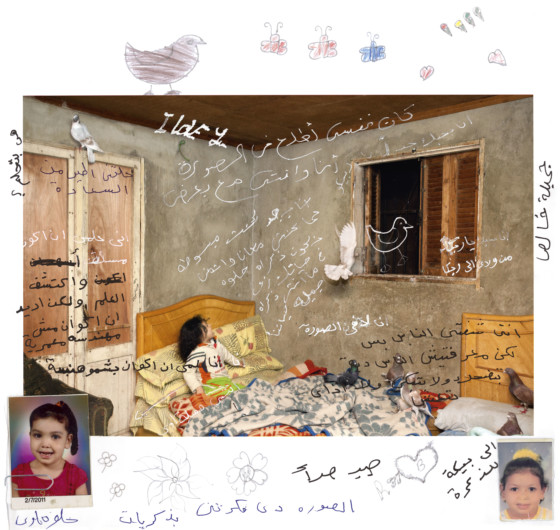

Bieke doesn’t take any photographs until she experiences a certain closeness. Each picture is the outcome of a meeting between people. The tableaux she captures take place in the hidden recesses of a home. She catches those elusive moments of trust and of secure silence that sometimes emerge at the end of the day. It is a stillness she herself also partakes in.

Without the exchanging of many words, evenings become nights. They communicate using a shared language of looks and gestures. There is cooking and playing, the neighbor comes by to borrow some eggs. The crumbs are shaken out of the rug, the stacked blankets are taken apart and spread out. The dining table becomes a bed, mother and children huddle close together in the cold winter night. Bieke falls asleep next to a snoring grandma, next to a girl with fitful dreams. She wakes up with a child under each arm—glowing cheeks and tangled hair. Pigeons fly into the room through the open window.”

"People are friendly, but Bieke senses how the private sphere is protected."

- Ruth Vandewalle

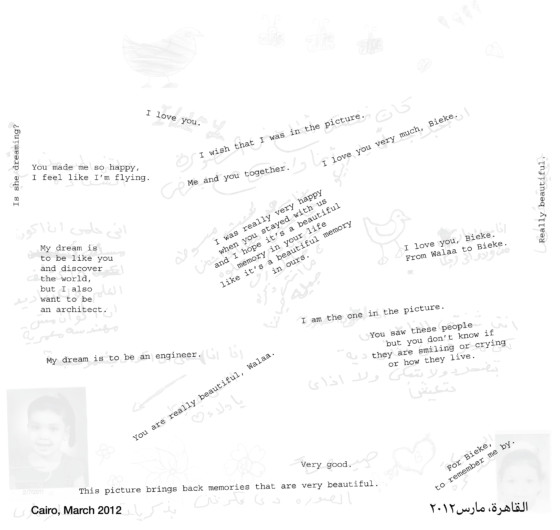

“As Bieke keeps trying to connect, she gradually becomes more aware of her status as an outsider, both culturally and as a photographer. Dialogue and interaction are important but Bieke remains a visitor from the West, a woman, a photographer.

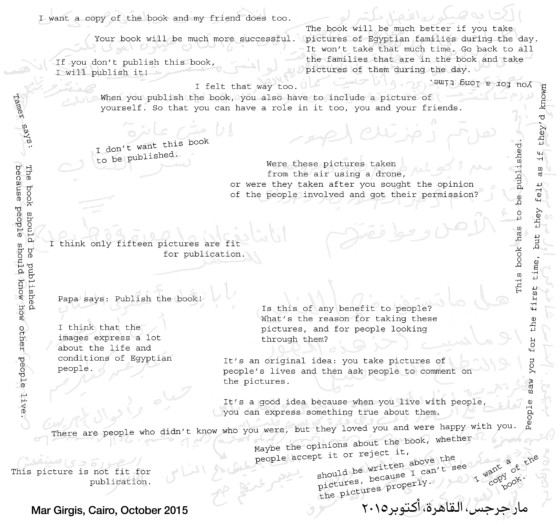

She decides to go back to Egypt with a first draft of her book. Her photographs themselves now become meeting places. Conversations sprout up in writing between people who would otherwise never have come together.”

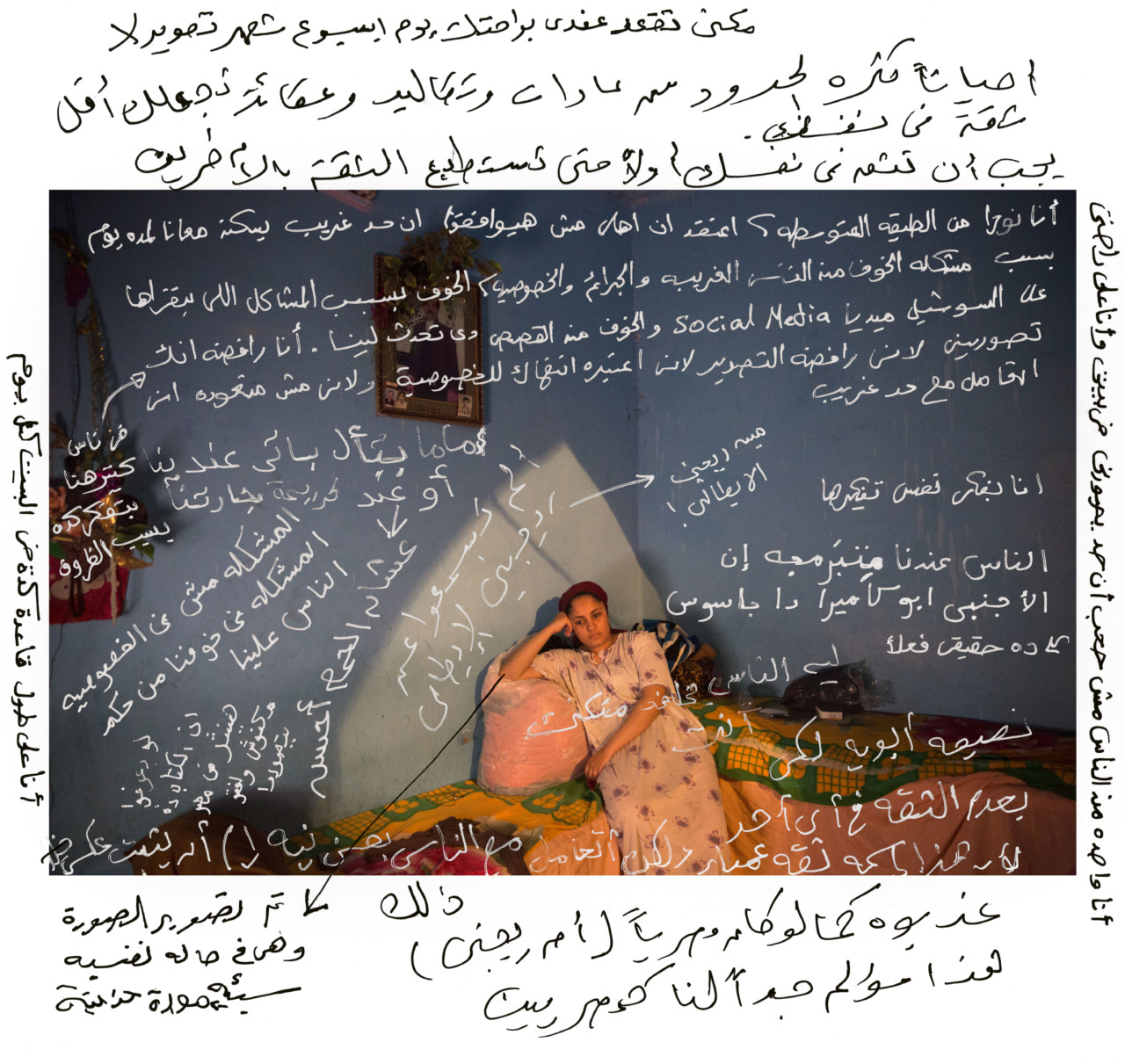

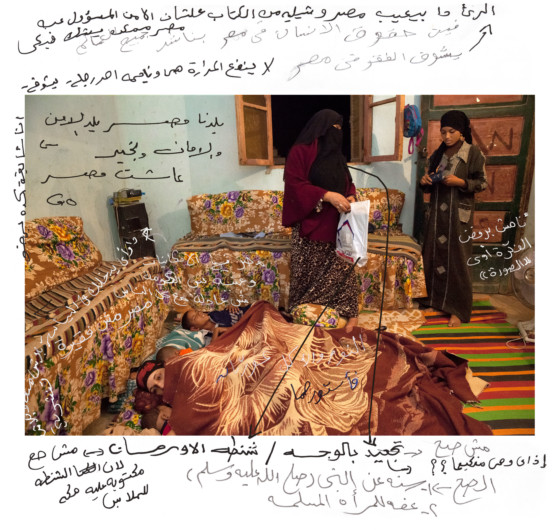

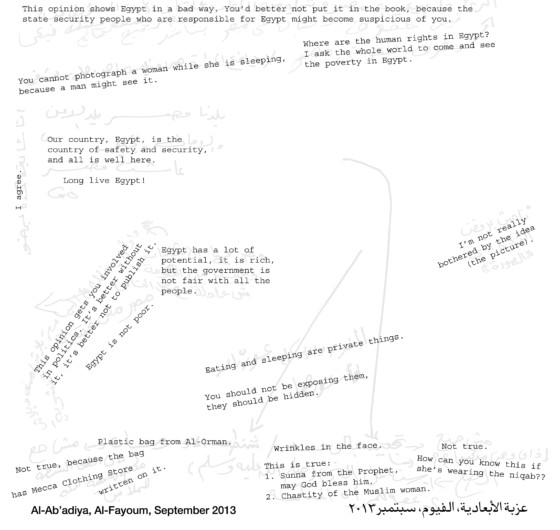

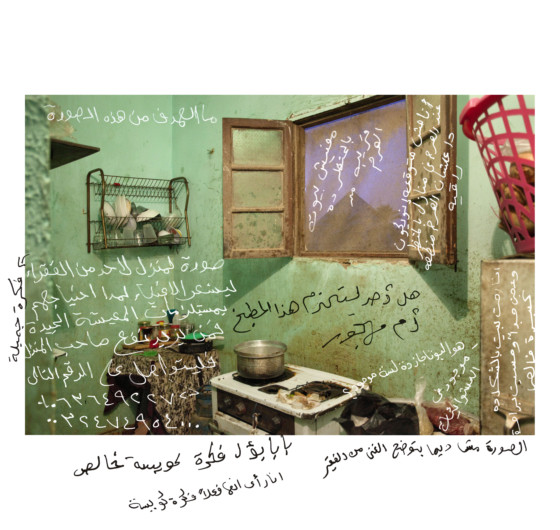

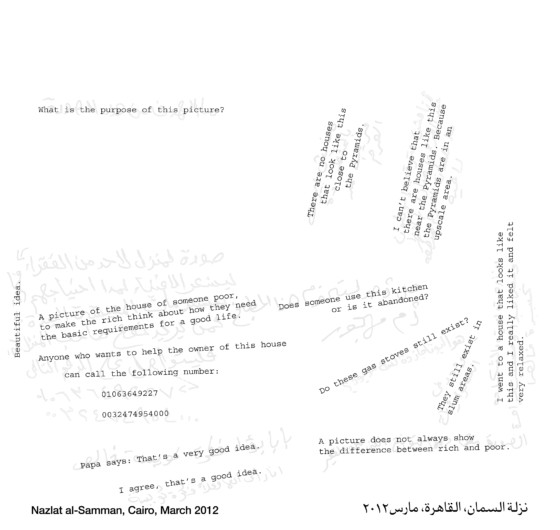

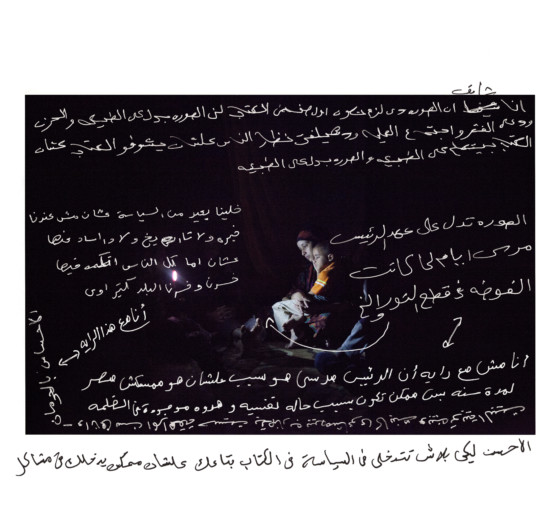

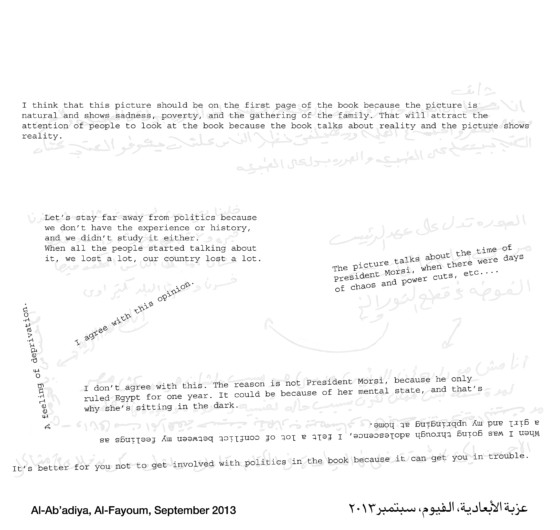

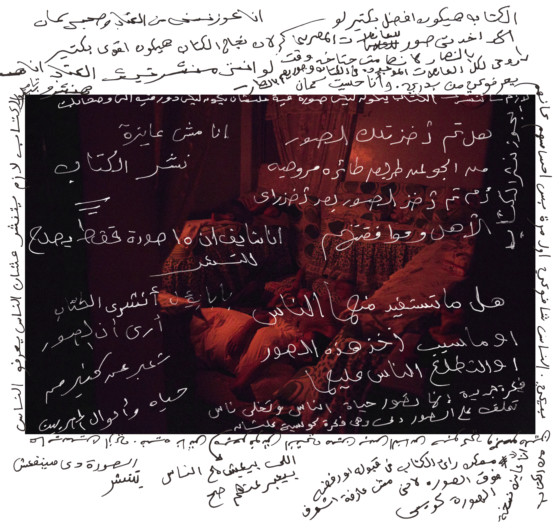

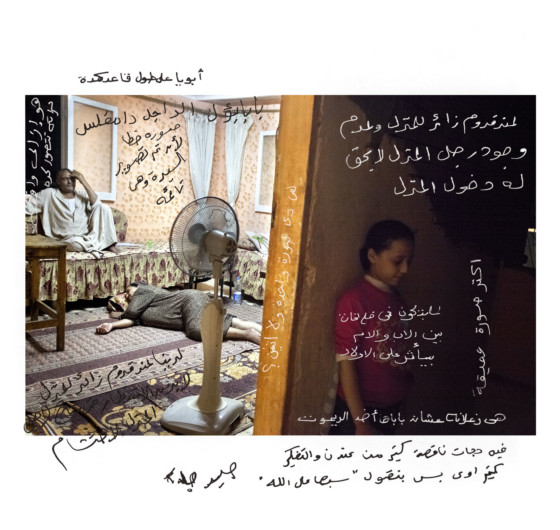

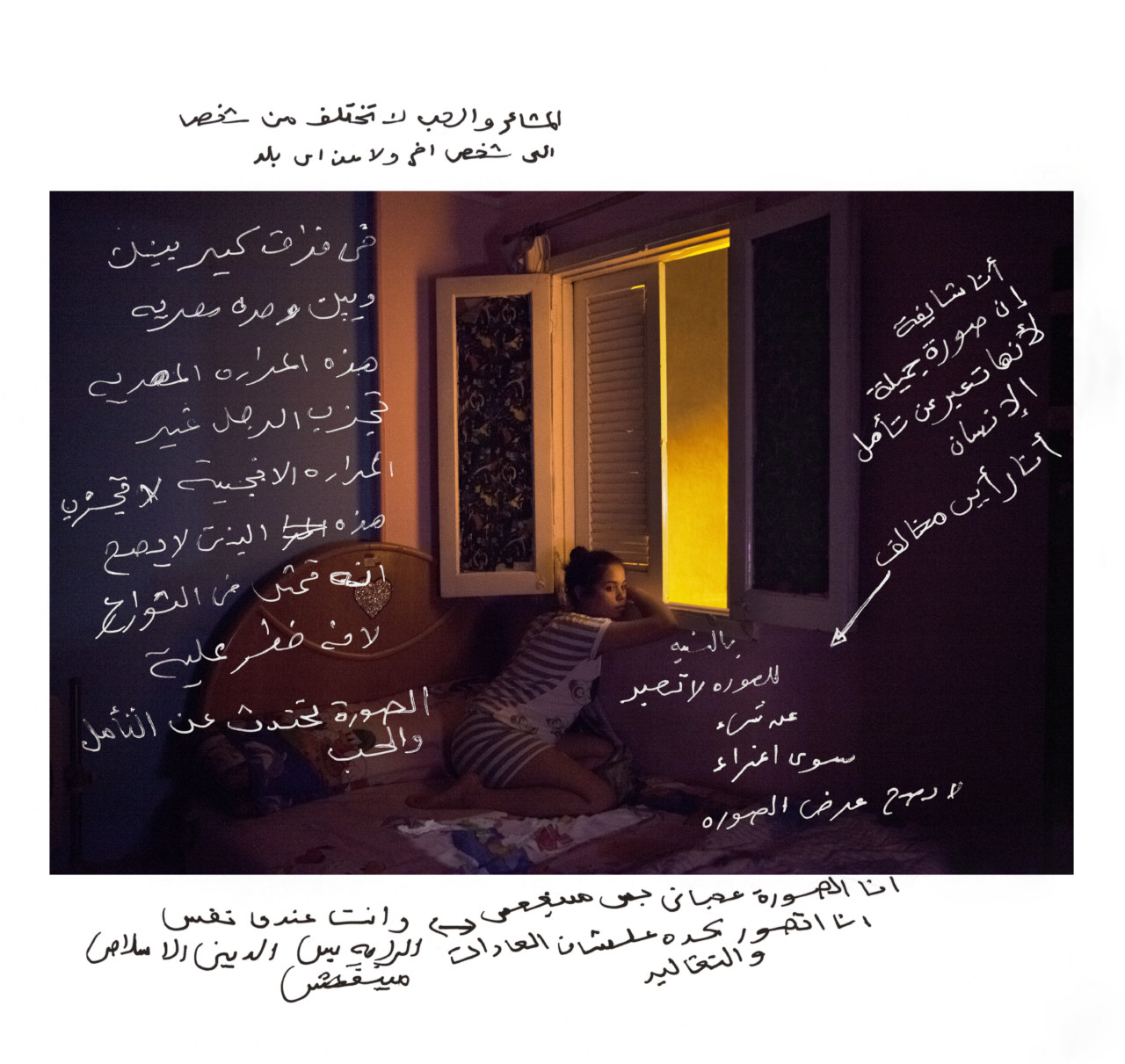

“People who might not have chosen to invite Bieke into their own house are also given a chance to add their voices to the book. About fifty passersby encountered in different parts of the country add a further layer to the book. They succeed in piercing the vacuum that the images seem to reside in. They read between the lines and through the blankets. The complexity of this society is embodied by the spelling mistakes, by the responses scribbled across the framed pictures on the walls and the pyjamas. The outside world invades the discussions held here, on class differences, education, privacy, and religion. When the subject is politics, people tread carefully. Even anonymous strokes of the pen can be compromising nowadays. It is March 2017 and self-censorship can feel safer than risking freedom of expression. Images that people don’t agree with become progressively less visible with each scrawled comment.

The photo is being overwritten as if suddenly adding subtitles to a silent film. The shifting perspectives challenge the viewer. More than ever, the image becomes just one possible interpretation of reality, as it may be. It can no longer be considered the only fixed truth.

The blue on the walls is still fresh, but the color is already worn out from the intensive living it provides a background for. In the small room, the four youngest children each try to carve out their own space. The evening is filled with colored pencils, math homework, and boys’ tears. Between two cartoons, the news announces a message from the outside world: Hosni Mubarak has been acquitted.”

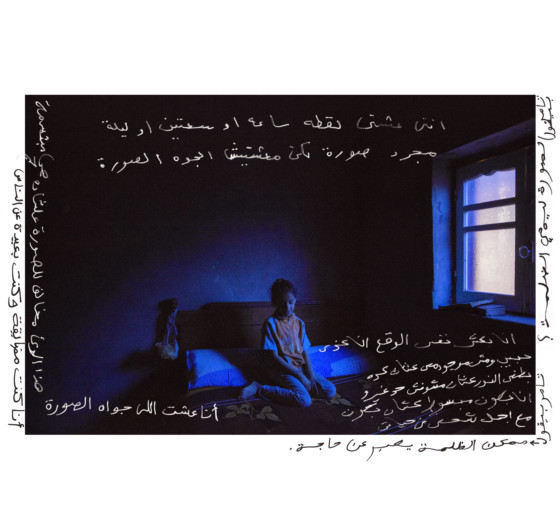

“Tens of thousands of members from the opposition are in jail. No one protests. The father doesn’t either, even if he’d like to. On the couch the mother is looking at the pictures in the book together with Bieke. In white she writes, above the girl in the bed:

‘You have lived through one snapshot—an hour or two, maybe a night. Just a picture. But you haven’t experienced what’s in this picture.’

No matter how close Bieke gets, their lives are not hers. With her images she succeeds in momentarily pausing time, as if nothing changes within the walls of the house.”