Vampira: The First Hostess of Horror

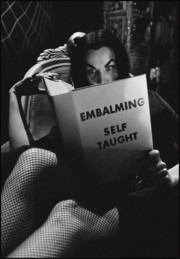

Dennis Stock's photographs of Maila Nurmi, America's "iconic combination of burlesque pin-up, old Hollywood glamour, and gothic chic"

To mark the Halloween season, film and culture writer Sabina Stent looks back on Dennis Stock’s photographs of one of America’s first horror heroines – Maila Nurmi, aka Vampira.

As a child, Maila Nurmi was not invited to Halloween parties. She considered herself awkward and gangly, but found solace and escape in fantasy novels and comic books, what she described as “the world of the vampire.” It was a universe that would eventuality become her reality.

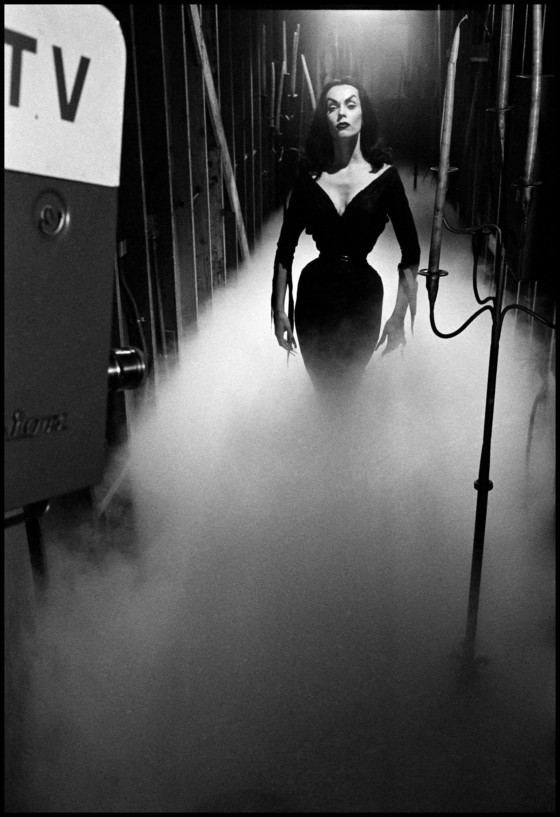

As Vampira, Nurmi became the first hostess of horror, an iconic combination of burlesque pin-up, old Hollywood glamour, and gothic chic. “The shock of Vampira came from her refusal to submit to the male gaze. She wanted to attack it instead,” notes Nurmi’s biographer W. Scott Poole. As Vampira, Nurmi became a pop culture icon and symbol of liberation in conservative America, an era when women were expected to carry out housework with a sense of duty and pride. At the height of her show’s fame and whenever in public situations, Nurmi never broke character, always presenting herself as Vampira: fitted low cut black gown emphasizing her impossibly cinched waist, arched eyebrows, black wig, and nonplussed behavior. Both Nurmi’s persona and politics entwined in Vampira, who potently subverted ideas of female beauty and how women were expected to behave. “There was so much repression,” Nurmi once reflected. “People needed to identify with something explosive, something outlandish and truthful.”

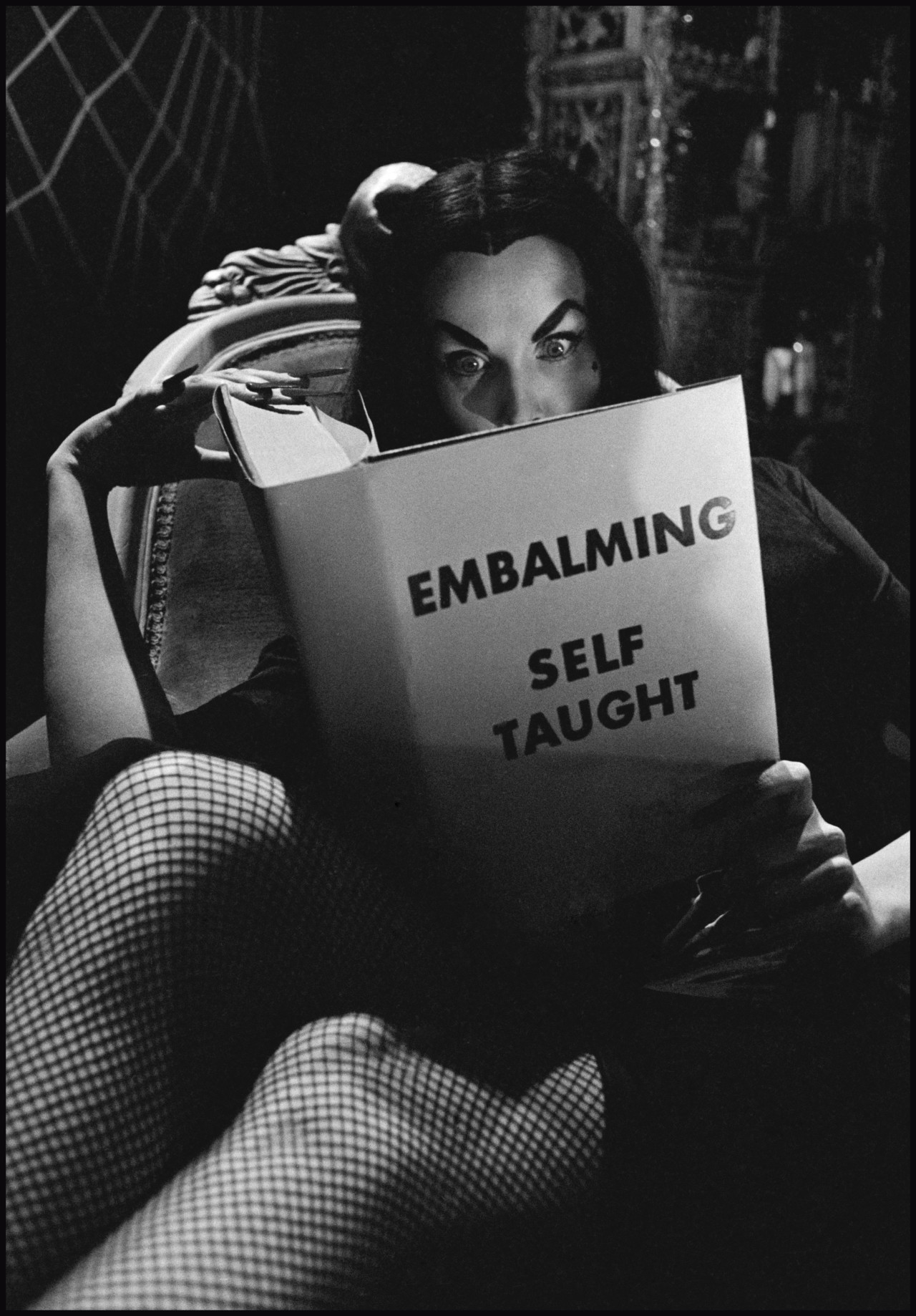

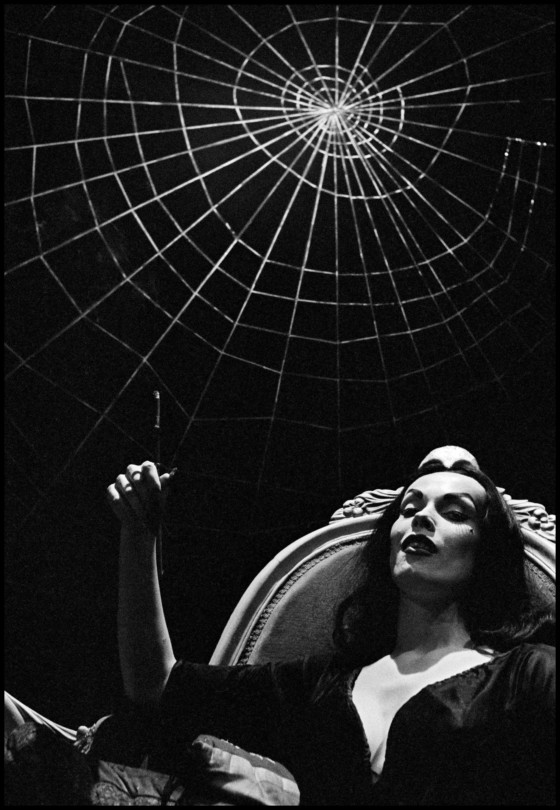

Nurmi, the daughter of Finnish immigrants, was raised in Oregon but moved to Hollywood in 1940 intent on becoming a movie star. Instead, she found fame on television as a fixture of late-night horror. It was an ironic twist as Nurmi came to embody what she had missed during childhood. “I found that as Vampira I was Halloween,” she would later say. At a 1953 Halloween party, Nurmi, dressed as Charles Addams’ Morticia, caught the attention of Hunt Stromberg Jr., a Los Angeles based television producer. Nurmi became Vampira, and The Vampira Show was born. Audiences instantly fell under her spell, insatiably consuming her dry humor, mocking movie introductions, trance-like walk, and deadpan puns. Reclining on a chaise longue, and surrounded by spiders, cobwebs, and other haunted house paraphernalia, she would invite viewers into her world while keeping them at a slight distance. They could look but never touch, a power move that only enticed and excited her audience.

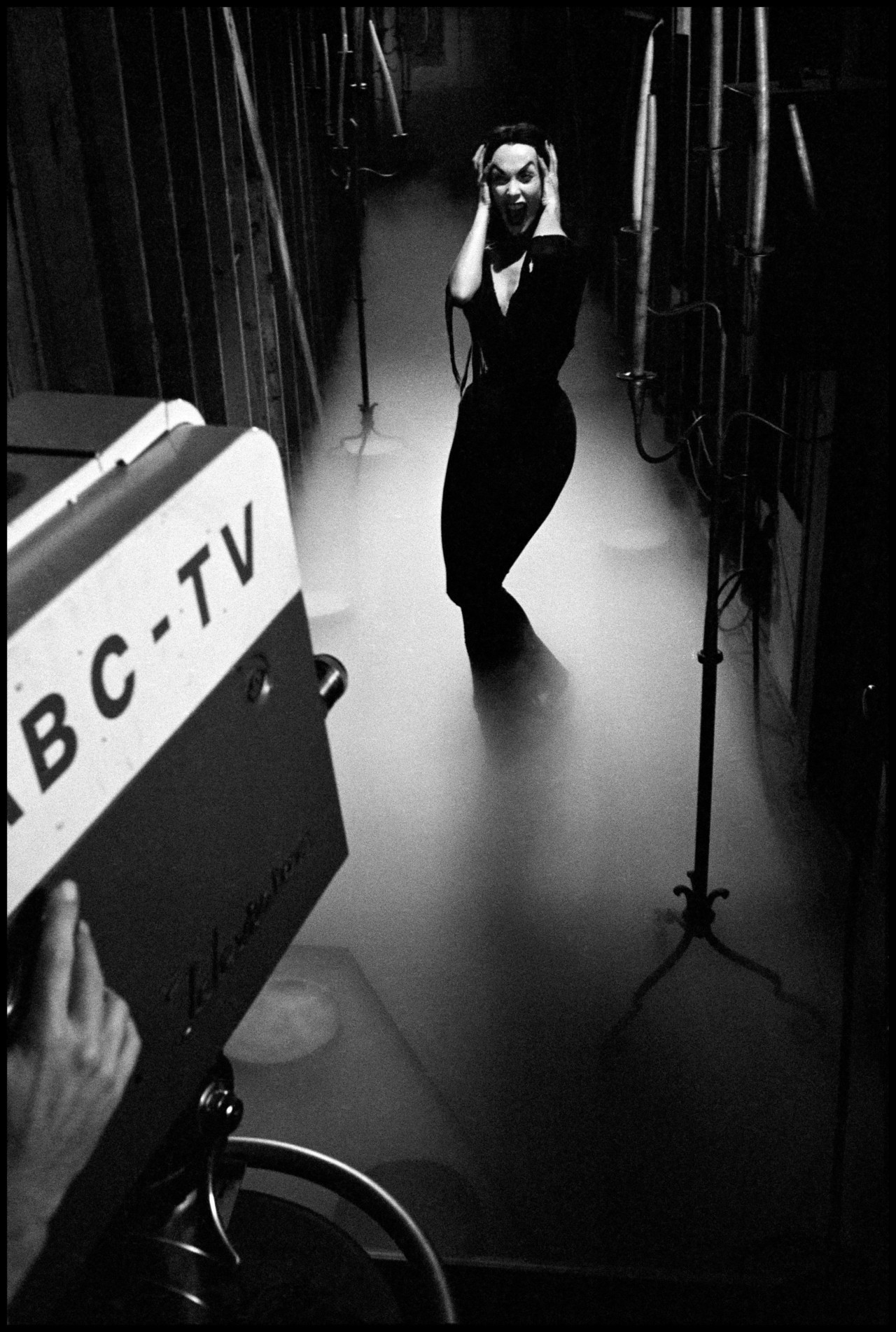

In Dennis Stock‘s photographs, Nurmi is captured both on set and out on the streets of Los Angeles. Always in character as Vampira, she never breaks the illusion for onlookers and fans. In front of a visible studio camera and surrounded by fog and dry ice, Nurmi stands in her familiar Vampira pose: arms hovering at her waist and elbows jutting out. It was a stance that would often signal the beginning of her zombie walk, a trance-like state that she popularized on the show, and reenacted in subsequent movies. As Vampira, Nurmi appeared in numerous projects by the infamous B Movie director Ed Wood, including 1959’s Plan 9 from Outer Space. At the time the movie was lambasted as the worst film ever made but has since achieved cult status and a loyal following.

Photographer Stock was famed for his New York photographs of James Dean, including the iconic image of Dean walking in Times Square in 1955, the year of Dean’s death. Dean and Nurmi became close friends, two outsiders caught in a tumultuously harsh yet glittering industry. Together they would frequent Hollywood coffee shops, including Googie’s Coffee Spot on the corner of Crescent Heights and Sunset Boulevard. “We had the same neuroses,” Nurmi would say of her late friend.

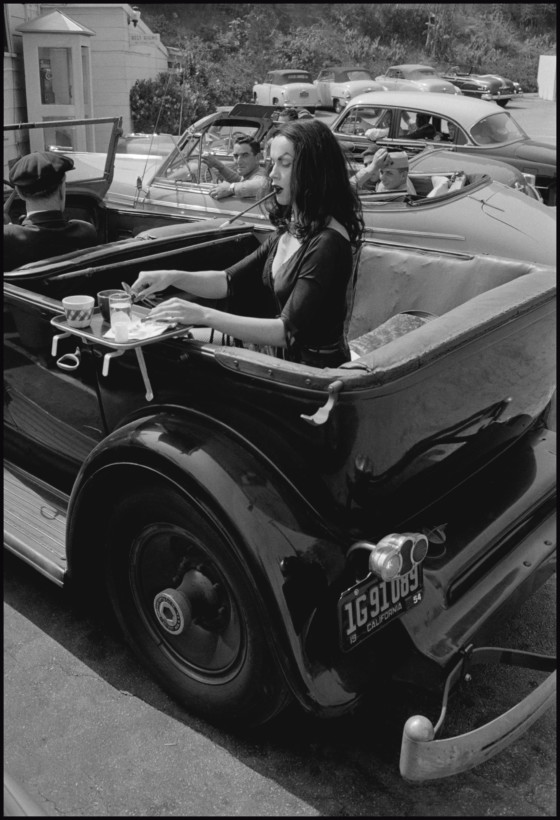

In the photographs taken in public, Stock captures Nurmi in the daytime, shattering the illusion that she only ventured out after dark. As the passenger in her chauffeur-driven, open-top, vintage 1951 hearse, she clutches a black spider-web parasol to shield her alabaster skin from the Los Angeles sun.

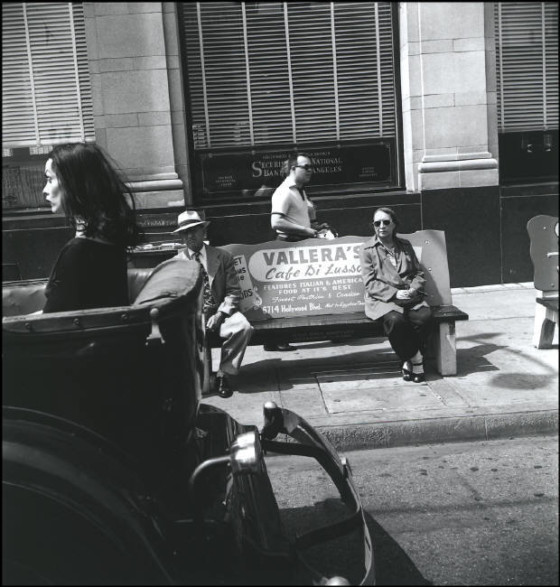

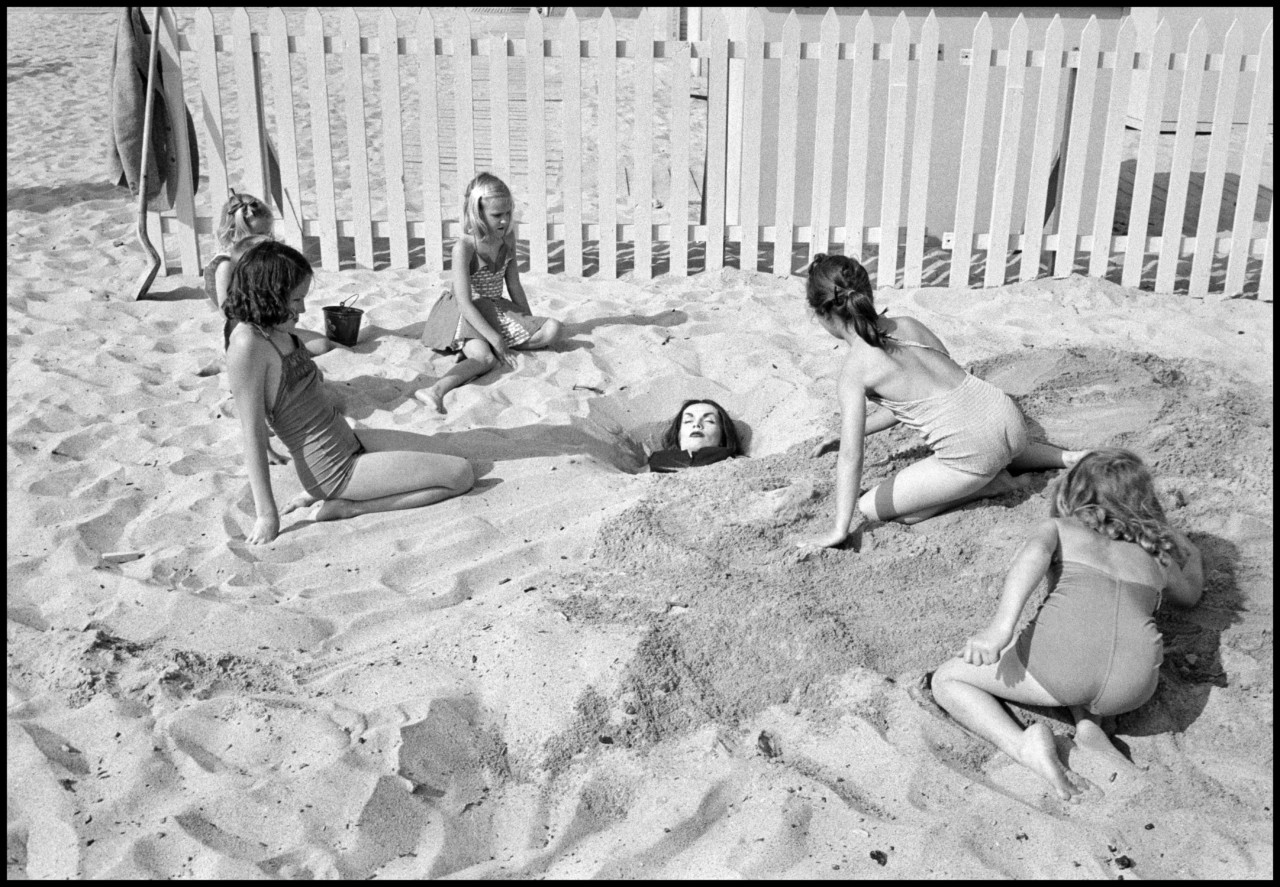

Nurmi was as popular with children who enjoyed her cartoon-like image as adults who appreciated her exaggerated comic book sexuality and self-deprecating dark humor. Out on the L.A. streets, we see Nurmi signing autographs for young fans in traffic, and attracting the glances of a group of young men at a Drive-In Diner. Like the lady on the bench whose eyes follow the car as it cruises past, all are unable to look away.

The Vampira Show ended in the late 1950s, and Nurmi eventually lost the rights to her trademark name. She died of natural causes in 2008 and was buried at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Nurmi’s grave, recognizable by the small and humble black plaque stamped with Vampira’s image, is to be found covered with lipstick kisses and little trinkets left as a dedication by adoring fans. Every year, at Hollywood Forever’s annual Halloween and Day of the Dead event, her grave is visited by a stream of adoring fans. Previously never invited to the party, she is now a permanent part of it instead.