Harlem Fashion

Eve Arnold rewrites the codes of fashion photography in 1950s Harlem, New York

Two of Eve Arnold’s portraits from this story are available as part of Magnum’s New York Fine Print Collection. You can see the full curation of New York products on the Magnum Shop.

Joining Magnum in 1957 as the agency’s first female photographer, Eve Arnold captured some of the most significant individuals and groups of the era. Arnold was self taught; the only formal training she received was a brief course at the New School for Social Research in New York, with Alexey Brodovitch, the renowned art director of Harper’s Bazaar. It was on assignment for this class that Arnold sought to address the artificiality of fashion photography in the 1950s, and at the same time give some attention to the black fashion world that was not acknowledged by the dominant fashion press of the day. In Harlem, a black area in a segregated New York, over 300 fashion shows were taking place a year. Arnold contacted an agent who supplied models for such shows, and he invited her to come and meet his star, Charlotte Stribling, known as “Fabulous”.

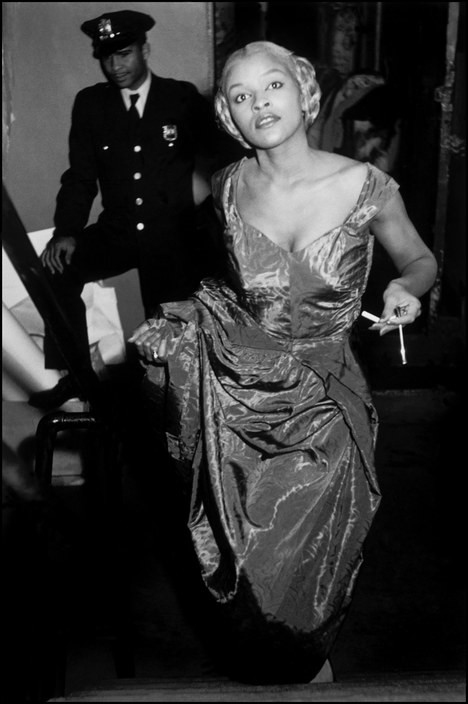

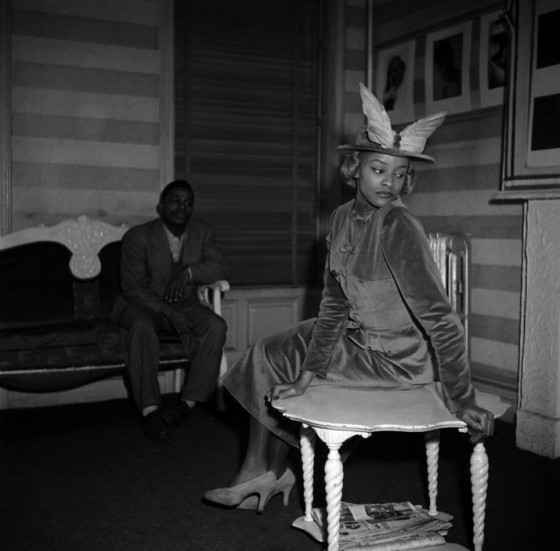

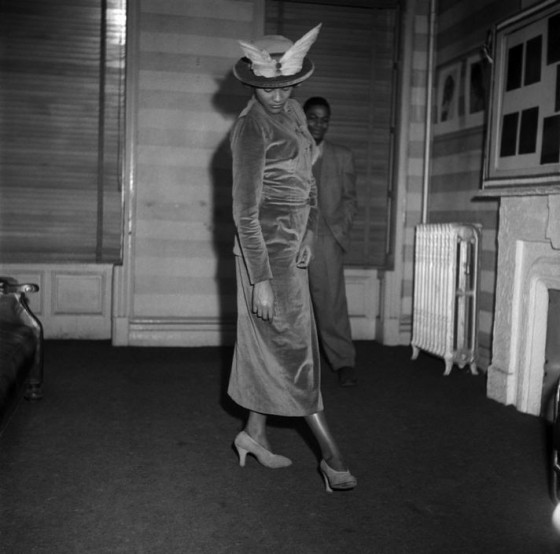

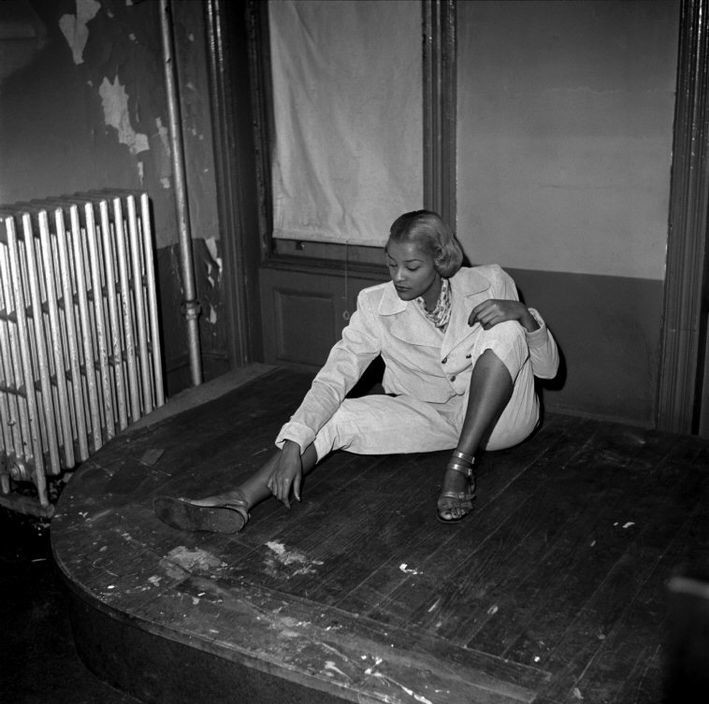

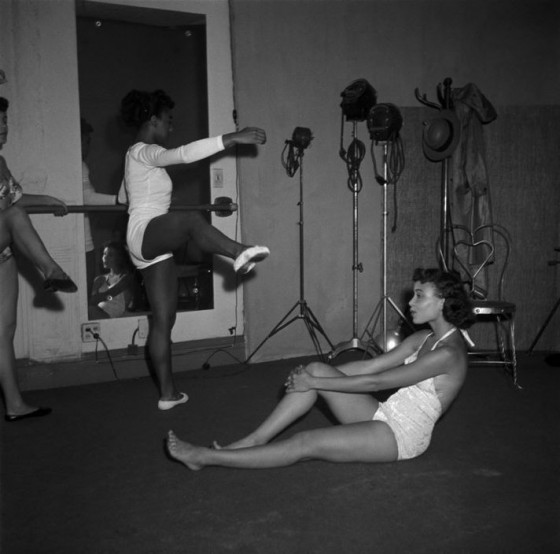

This career-making photo-essay, which Brodovitch praised for its “freshness”, captures a vibrant community at the center of the civil-rights movement. Taking place in a deconsecrated Abyssinian Church, the fashion show was just one of a multitude of events that showcased the work of local black designers, modelled by black models. The shows were both celebrations of the local culture and a form of protest against the white-dominated fashion industry that largely ignored them. Inspired by what she experienced, Arnold went on to spend the following year in various church halls, bars and restaurants documenting the local fashion models and seamstresses both backstage and at home.

Arnold’s attendance at the shows came as a surprise to the all-black audiences and their awareness of her initially made it difficult to produce photographs that did not look staged or unnatural. By following the models backstage however, she managed to capture the candid shots of these women she so desired, an approach that was not only unusual in this setting, but also unheard of in fashion photography at that time, where imagery was elaborate and staged. Now, the candid backstage shots of fashion shows are more ubiquitous than runway photography, but back then it was mould-breaking. Arnold later remarked, “I was not aware that you didn’t follow them – and I’ve done it over the years … simply out of a wish to learn, not to be prurient”.

"I was not aware that you didn’t follow them - and I’ve done it over the years … simply out of a wish to learn, not to be prurient"

- Eve Arnold

From two participants engrossed in inspecting their makeup pre-show, to a model squeezing out of a corseted garment backstage, her images depict the most intimate of moments. Finding ways to fade into the background would become a trademark of her practice and a defining quality of the work she produced, from introspective portraits of celebrities to her in-depth documentation of Malcom X and the Black Muslims.

"I always believe when you’re photographing somebody it’s generally a collaboration"

- Eve Arnold

Many of the photographs capture one of the most celebrated models on the scene, Charlotte Stribling, or “Fabulous,” as she was better known. “I always believe when you’re photographing somebody it’s generally a collaboration,” noted Arnold. From images of Stribling walking the catwalk with her trademark blond-hair, to stills of her prancing about back-stage, her awareness and understanding of how to act in front of the camera is evident. Eve was well aware of her powerful presence, describing Stribling as moving “like a golden animal—a leopard, perhaps, or a tiger.”

The shows were held in venues that varied from bars and nightclubs to churches. Navigating these often poorly-lit environments presented another challenge for Arnold. “I wound up shooting in badly lit rooms without additional lights and then spending hours developing and pushing to film to get a moody murky print,” she remembers. Armed with just her forty dollar Rolleicord and nothing else, learning how to make the most of the available light was crucial. This technique, and the natural quality with which it imbued her images, would remain a trademark of her photographic style.

Brodovitch was so impressed by the series that instead of having her complete the next class assignment he suggested she continue to return to Harlem. Her dark and un-manicured stills stood in stark contrast to the polished aesthetic of fashion photography of the day. By applying her distinctly natural photographic style to this subject matter, Arnold had somewhat unwittingly produced a photo-essay that offered a new direction for the genre.

"I wound up shooting in badly lit rooms without additional lights and then spending hours developing and pushing to film to get a moody murky print"

- Eve Arnold

No American picture magazine was interested in the series and without consulting her, Brodovitch proceeded to send Arnold’s photos to a contact at the Picture Post in London. Published later that year, the photographs were accompanied by text that Arnold felt wholly mis-represented the project. Realizing the importance of retaining editorial control, Arnold spent the rest of her career devoted to involving herself in the publishing process and regularly supplying the words that would accompany her work. Today, the series remains a powerful documentation of a lively sub-culture from a time when positive portrayals of black communities were rare.

Fine Prints from Eve Arnold’s Harlem work are avaialble from Magnum Fine Prints on the Magnum Shop here.