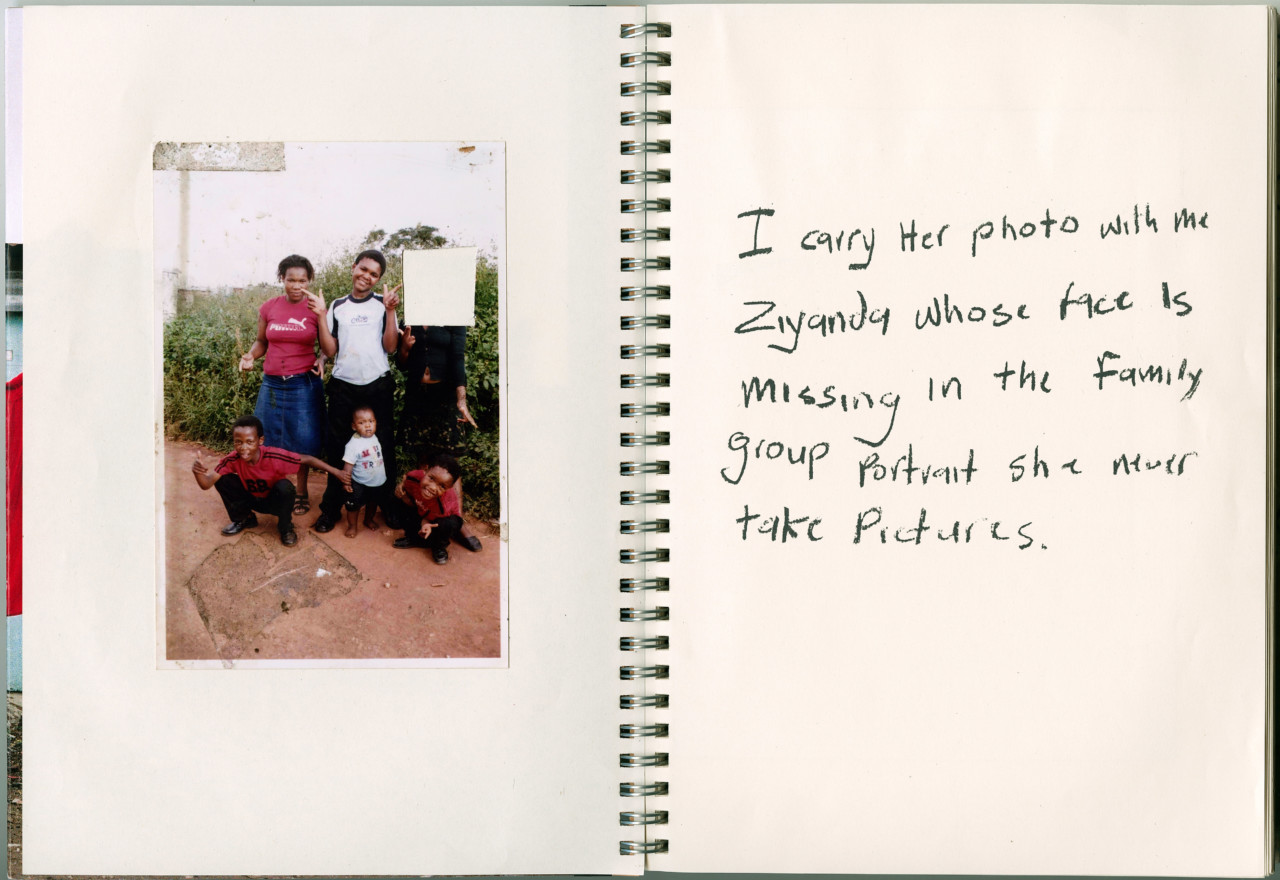

I carry Her photo with Me

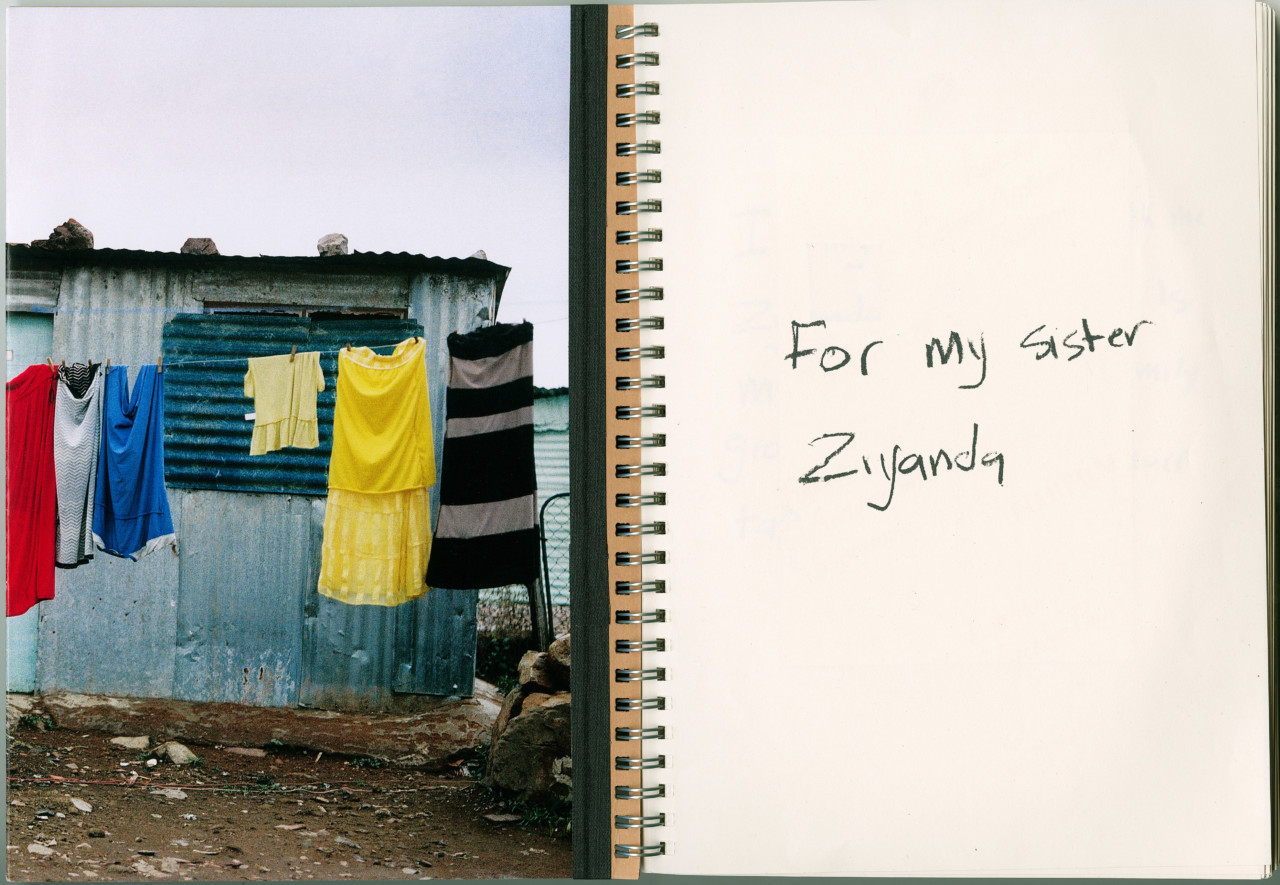

Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s new project saw him unraveling the story of the sister he lost

Lindokuhle Sobekwa only has one photo of his older sister Ziyanda. It’s a family portrait; her face is cut out of the picture. Looking inside his mother’s Bible one day in 2017, the South African photographer and Magnum nominee came across the altered group photo. Looking at it triggered some memories— good and bad — of a sister he had barely known, which had been lingering in his mind since childhood.

2002 was the year Ziyanda ran away. The siblings, aged 7 and 13, had been arguing over some money given to Sobekwa by his father which she wanted to take from him; she chased him; the boy was hit by a car.

“I remember nothing but a blurry female figure standing over me, and then I was in the hospital. I don’t know if the female ghost standing over me was Ziyanda, or maybe it was the woman who lived nearby who called the ambulance. My spine was broken. I was in the hospital for three months. From that day on, I didn’t see Ziyanda for 15 years,” reflects Sobekwa.

Sobekwa never got the chance to resolve any of his questions about her disappearance with Ziyanda before she became ill and passed away, shortly after her return to her mother’s home. Sobekwa’s family had to cut her only portrait out of the family picture so that they could use it for her funeral.

"My spine was broken. I was in the hospital for three months. From that day on, I didn’t see Ziyanda for 15 years."

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

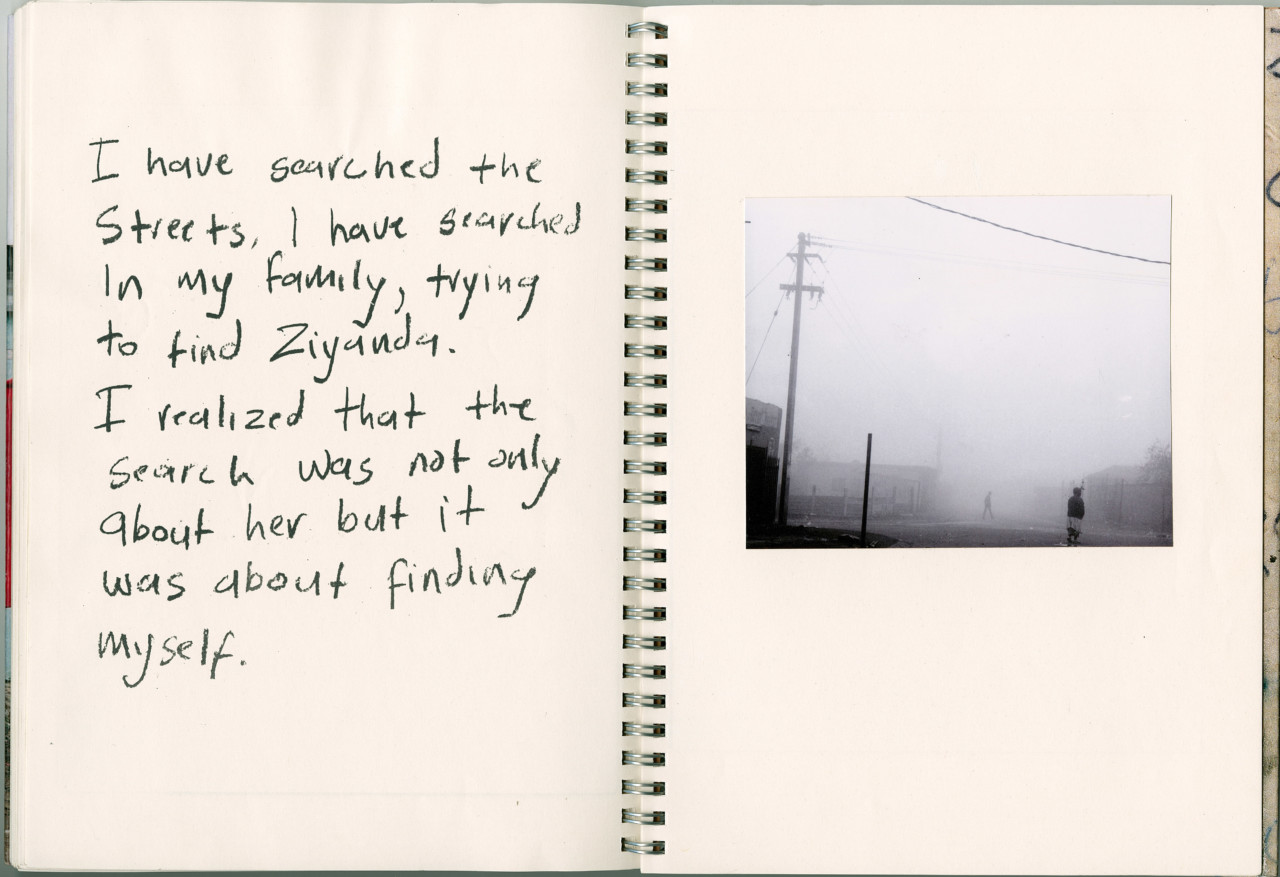

The photographer was undertaking his Magnum Foundation Photography & Social Justice fellowship in 2018 when he embarked on the project. Titled I carry Her photo with Me, it came together from his urge to seek out people who had known Ziyanda, in order to retrace her life through the places she had been and piece together her story. He decided he would take his camera and Ziyanda’s tiny cut-out portrait with him, making interviews and recording the places he saw. He didn’t have any kind of outcome for the work in mind. “I just wanted to find answers for myself, I wanted to find part of me that I had lost in that process, and I wanted to confront my family,” he says, “I was always asking myself, ‘What kind of life did my sister live, all those years when she wasn’t home?’”

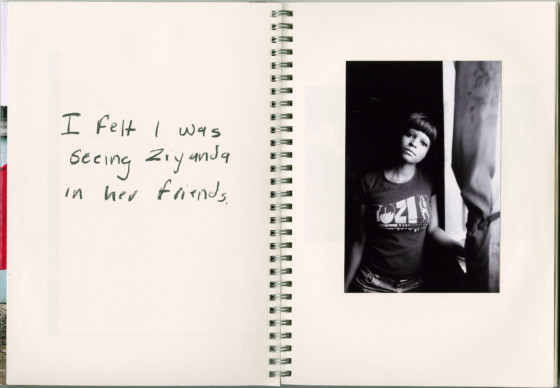

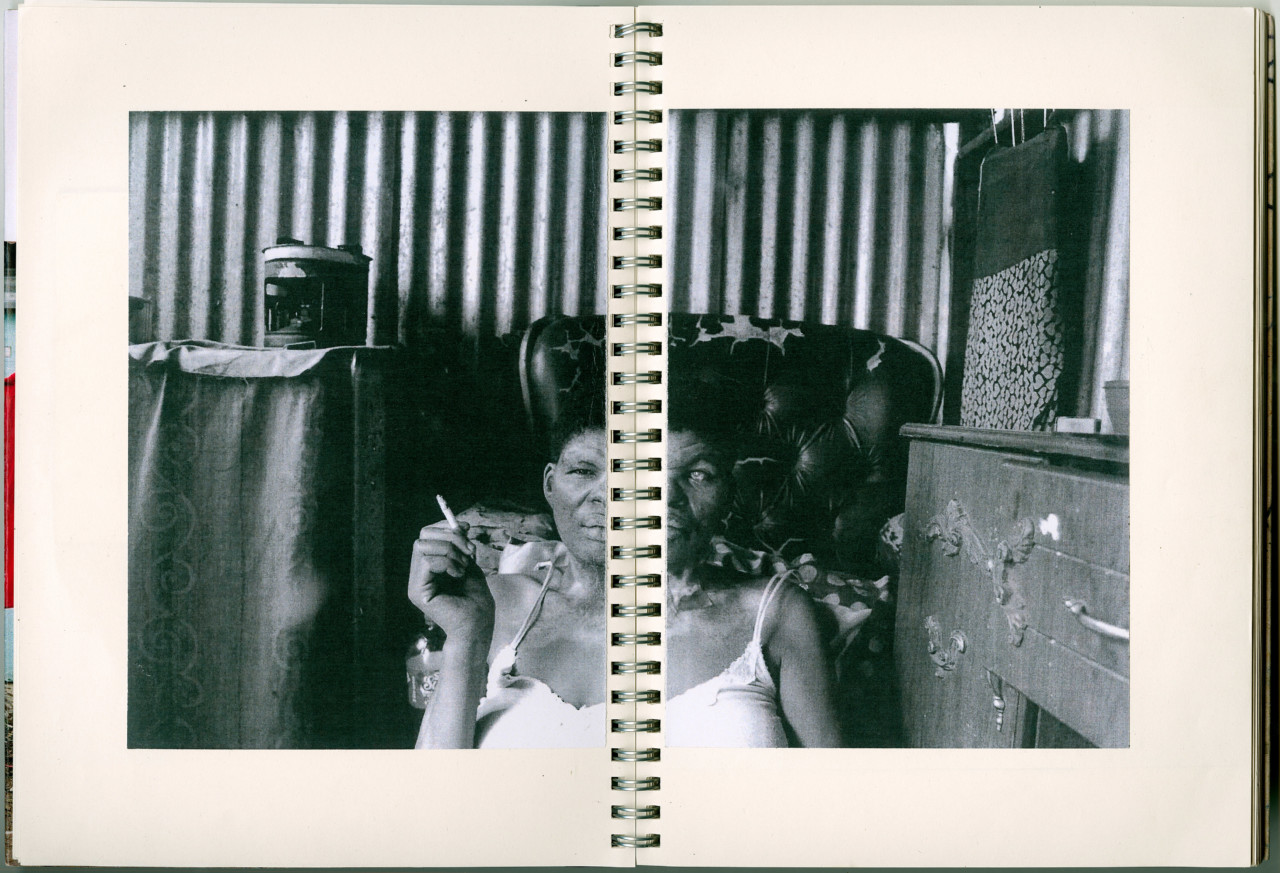

Sobekwa says that making pictures helped him to speak to people who were acquaintances of Ziyanda’s. Just as he had done when he was working on his project Nyaope, Sobekwa found that it was easier to gain access to people’s lives and stories when he had his camera.

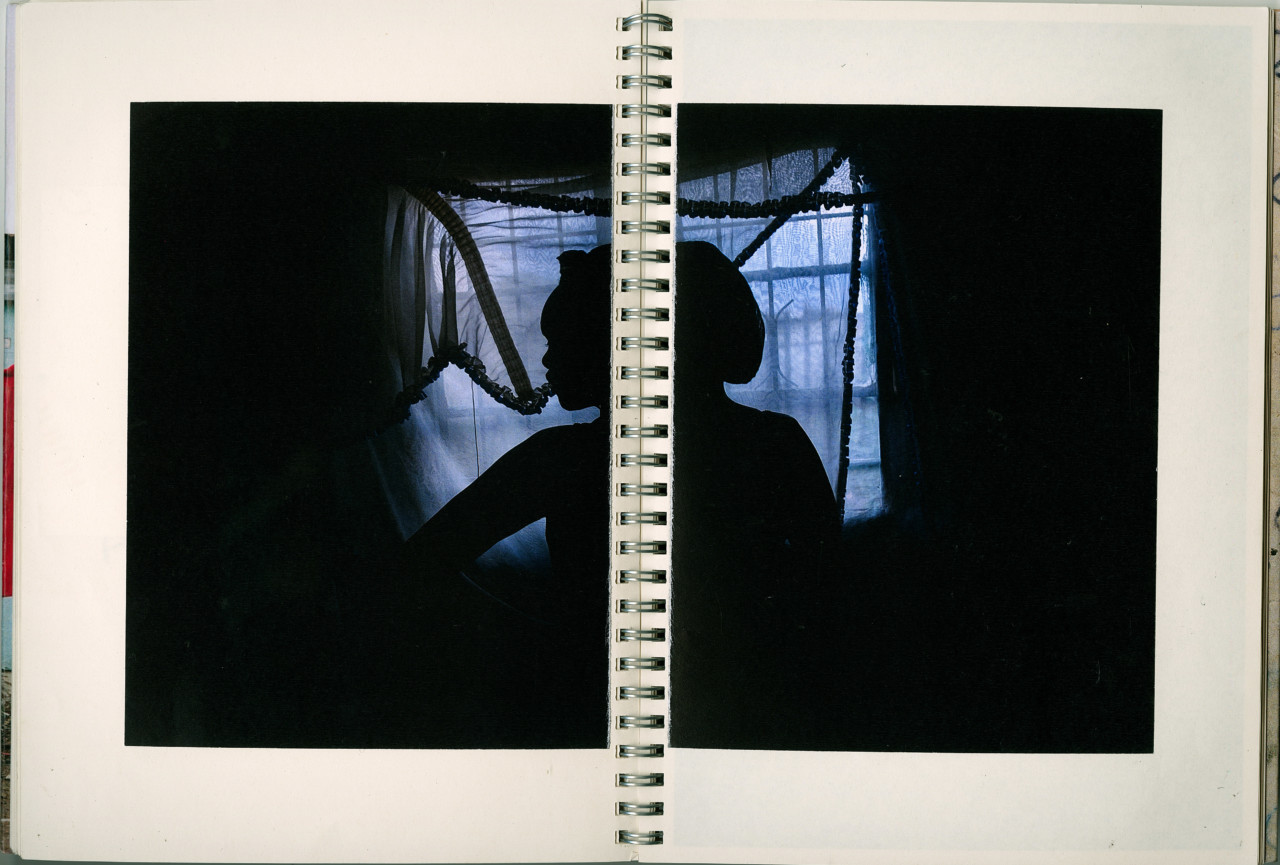

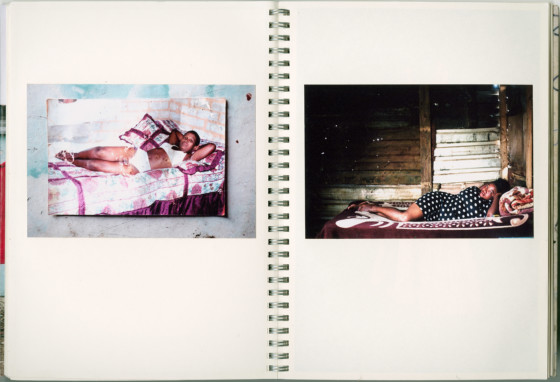

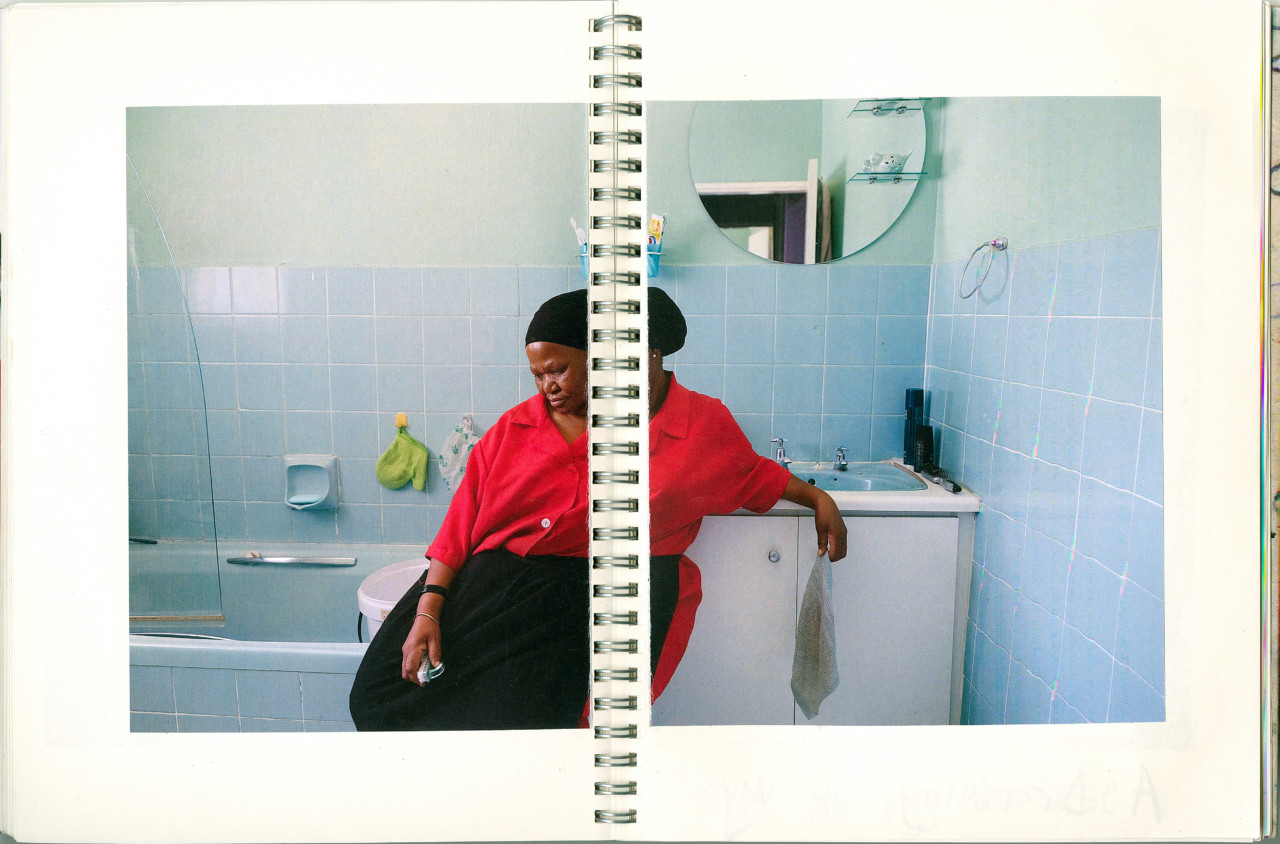

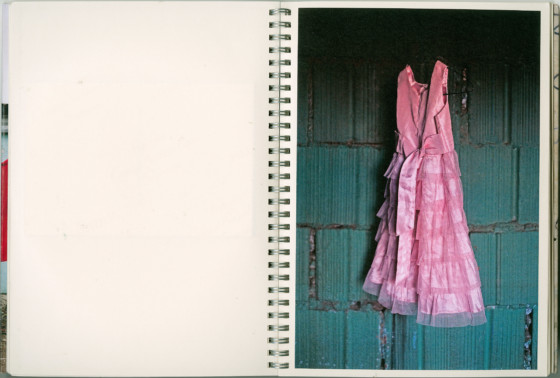

Sobekwa began taking photos in color at the beginning of his photographic career, before discovering the influence of Ernest Cole and Santu Mofokeng, who were the inspiration behind his shift towards black and white in the Nyaope project. Nyaope, a social documentary project in a more traditional sense, is shot in black and white, while I carry Her photo with Me mixes black and white and color images. Sobekwa jokes that the motivation behind the aesthetic change is a cliché: “I’m married to black and white and color is my child. I have the same love for both of them. I love to experiment,” he says before adding, “Ziyanda liked colourful stuff. She was a person ‘of color’ — she liked the colors red, yellow and orange.”

Starting a conversation

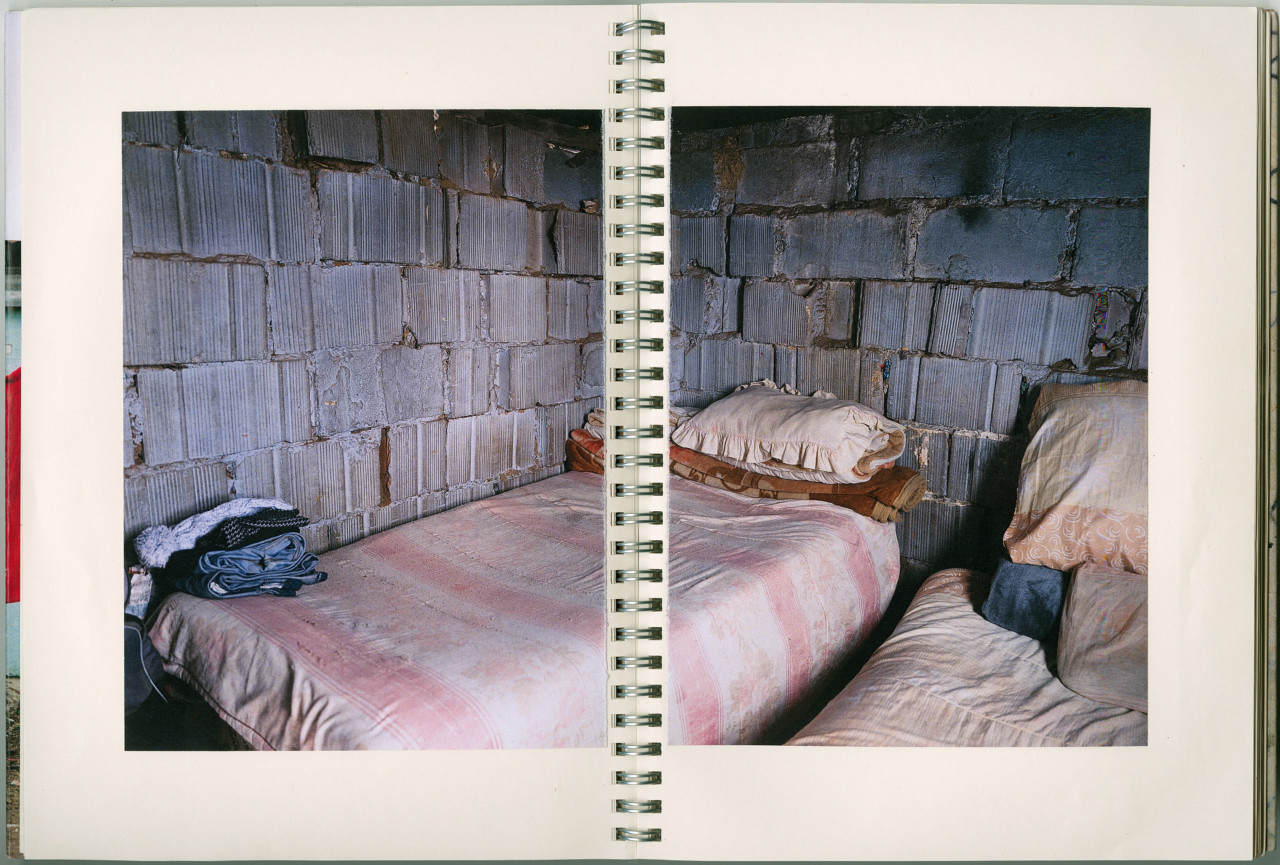

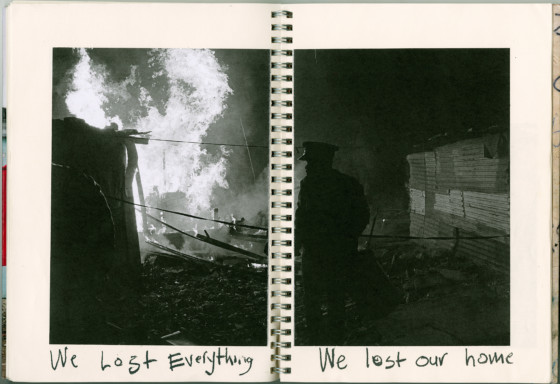

While I carry Her photo with Me originates in highly personal circumstances, the work reveals the wider issues which underlie those circumstances. Sobekwa cites the trauma that his community experienced as a result of factional wars in the 1990s, between the ANC and IFP parties, as having a major impact in the emotional development of his family. During one period of his childhood, Zulu soldiers patrolling Sobekwa’s area were killing young boys; people were terrified, Sobekwa’s mother included. Many friends have uncles suffering from mental illnesses like PTSD as a result of past experiences, he explains, as an example illustrating the ways in which trauma still resides in these local communities.

"Home is always a distant place where our fathers or mothers were born. Home is always where our ancestors were from. Joburg is never home. It’s a place to live, to look for jobs and opportunities."

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

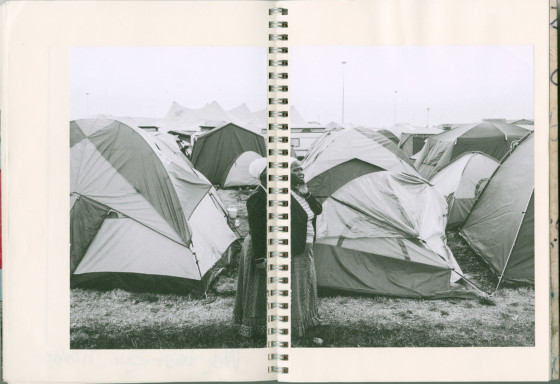

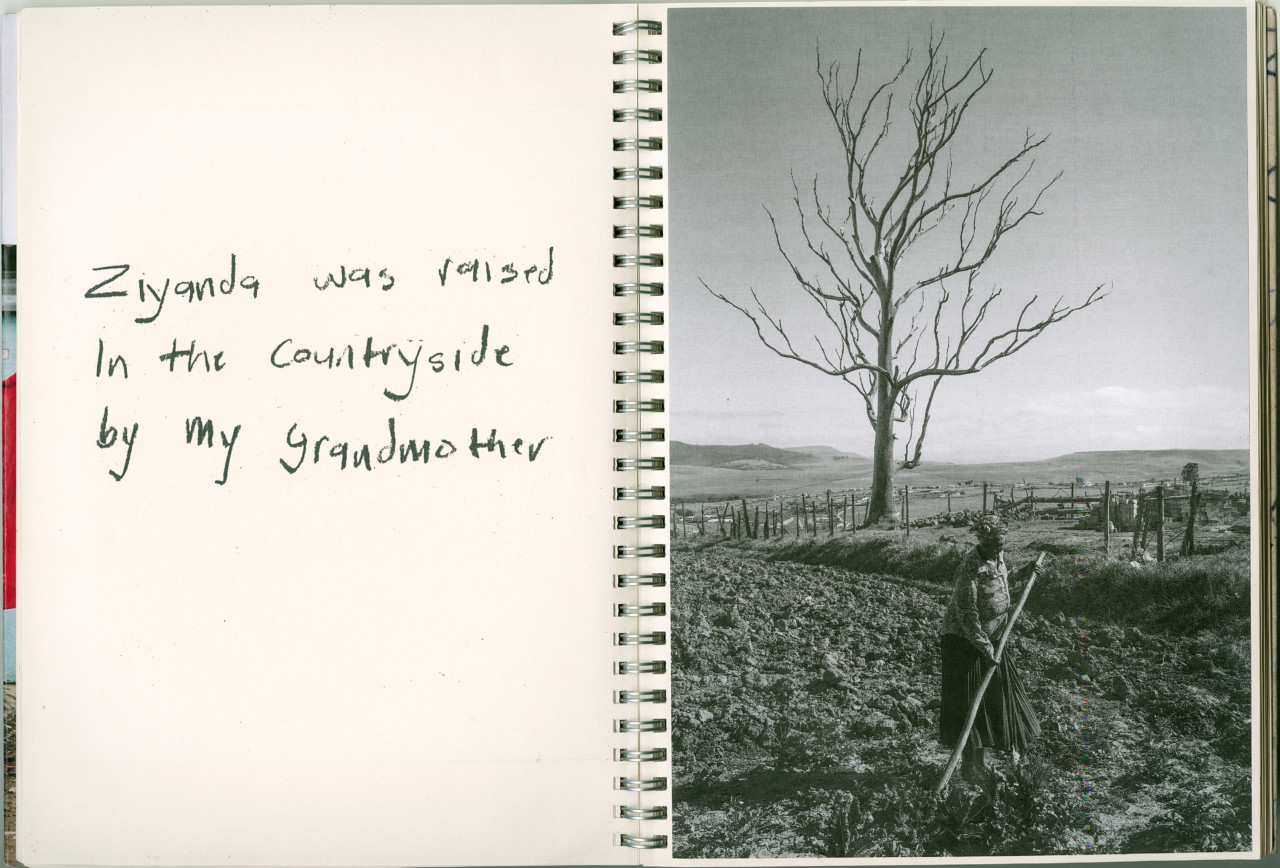

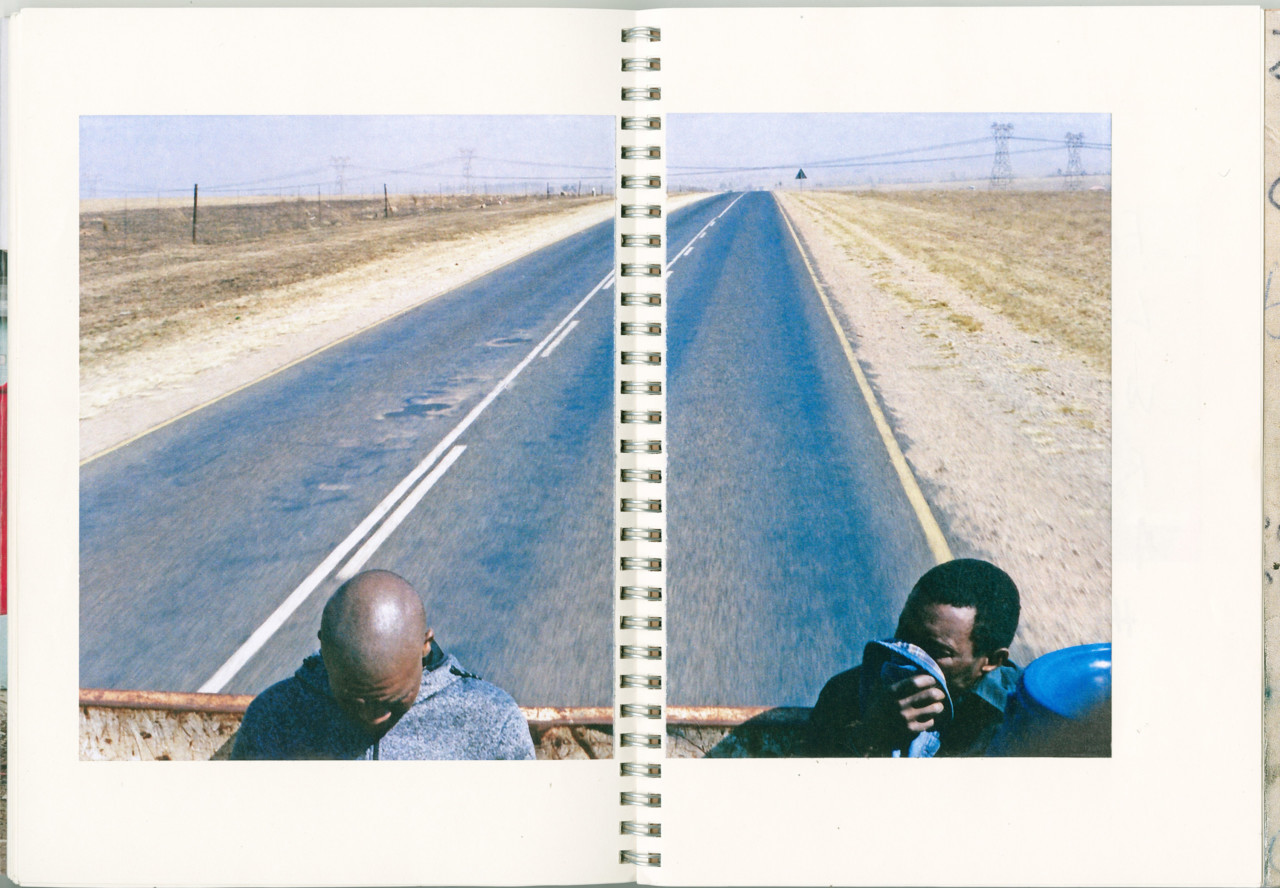

Migration into the city from outer areas has also been a factor in the fragmentation of families: “A lot of things got lost in the process of people coming to Johannesburg. Back in the 60s when my grandfather left to work in the mines my mother was one year old. He never came back home,” Sobekwa says. “Home is always a distant place where our fathers or mothers were born. Home is always where our ancestors were from,” the photographer continues, “Joburg is never home. It’s a place to live, to look for jobs and opportunities.” This employment-related migration into the city is still taking place. “My grandmother demonizes Johannesburg as a place that has swallowed all of this family — my mother’s siblings, my mother, us,” Sobekwa says. Ziyanda spent most of her childhood living at her grandmother’s house in the country, whilst Sobekwa’s mother was rarely home, travelling frequently to the city for her work as a domestic cleaner. “Maybe, to Ziyanda, it was usual for her family to feel like strangers.”

“I shared my story with the Nyaope guys and I realised we all came from the same systems, the same trauma. Growing up without a father figure, a mother figure. We could all relate to those cycles,” Sobekwa says. “This project on Ziyanda is not a unique story. A lot of people, in Thokoza especially, have experienced that [loss, and family break-up].”

Sobekwa’s family —especially his mother — had always found Ziyanda a sensitive topic of conversation. “Doing this project was difficult in the sense that you’re dealing with something that not everyone is willing to talk about, something that’s affecting you and other people. I’m not very good at expressing myself verbally so this was one way to say, ‘Let’s talk about it’”. Another relative of the Sobekwa’s, a half-cousin, also disappeared, in Cape Town. “This project is [an effort] to break that cycle of disappearances in my family.”

“There was this culture of excluding children from mourning, which I think affected a lot of children,” Sobekwa adds, before relating the story of his girlfriend, whose mother passed away in a car accident when she was young. She was forbidden from seeing her mother’s body. He believes she too suffers from deep-rooted trauma, which she carries from that incident — “the doubt of not knowing if that was her mother in the casket.” These deeply-ingrained early experiences are common amongst people he grew up around; “it’s a cycle that has become normalized through culture”.

Yet the topics dealt with in I carry Her photo with Me can have a relevance beyond Sobekwa’s own family, and beyond local and national contexts: “The project is really for myself, but also for my family and anyone who can relate to it. You don’t have to be from South Africa. The experience of disappearance, of losing someone and of grief is a universal thing. We all experience it, albeit differently,” Sobekwa says.

Creating a diary

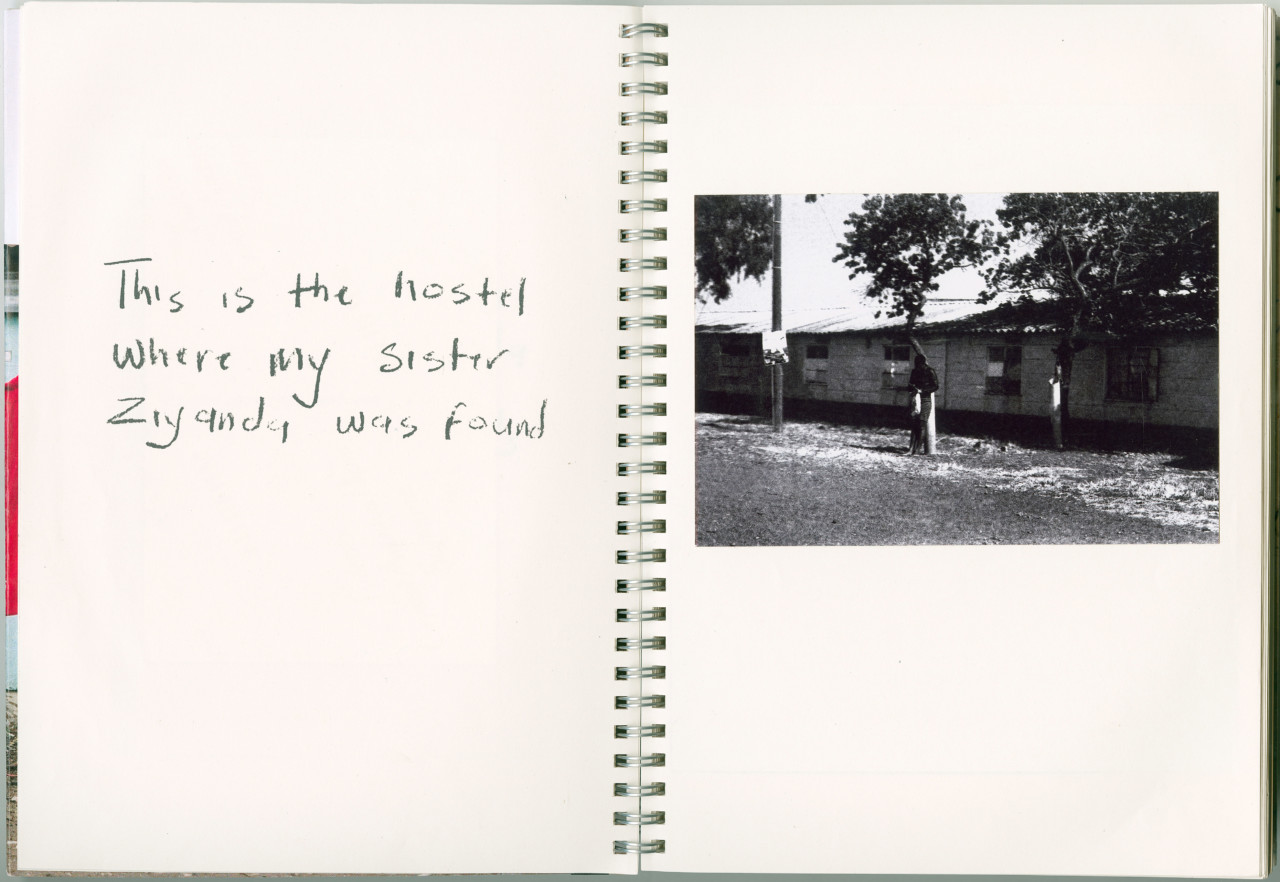

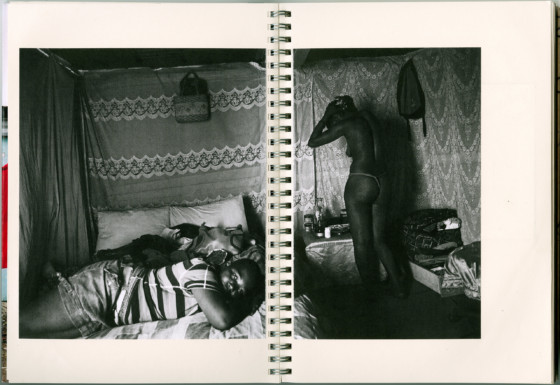

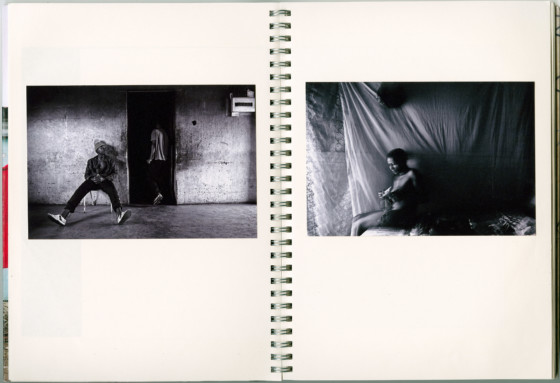

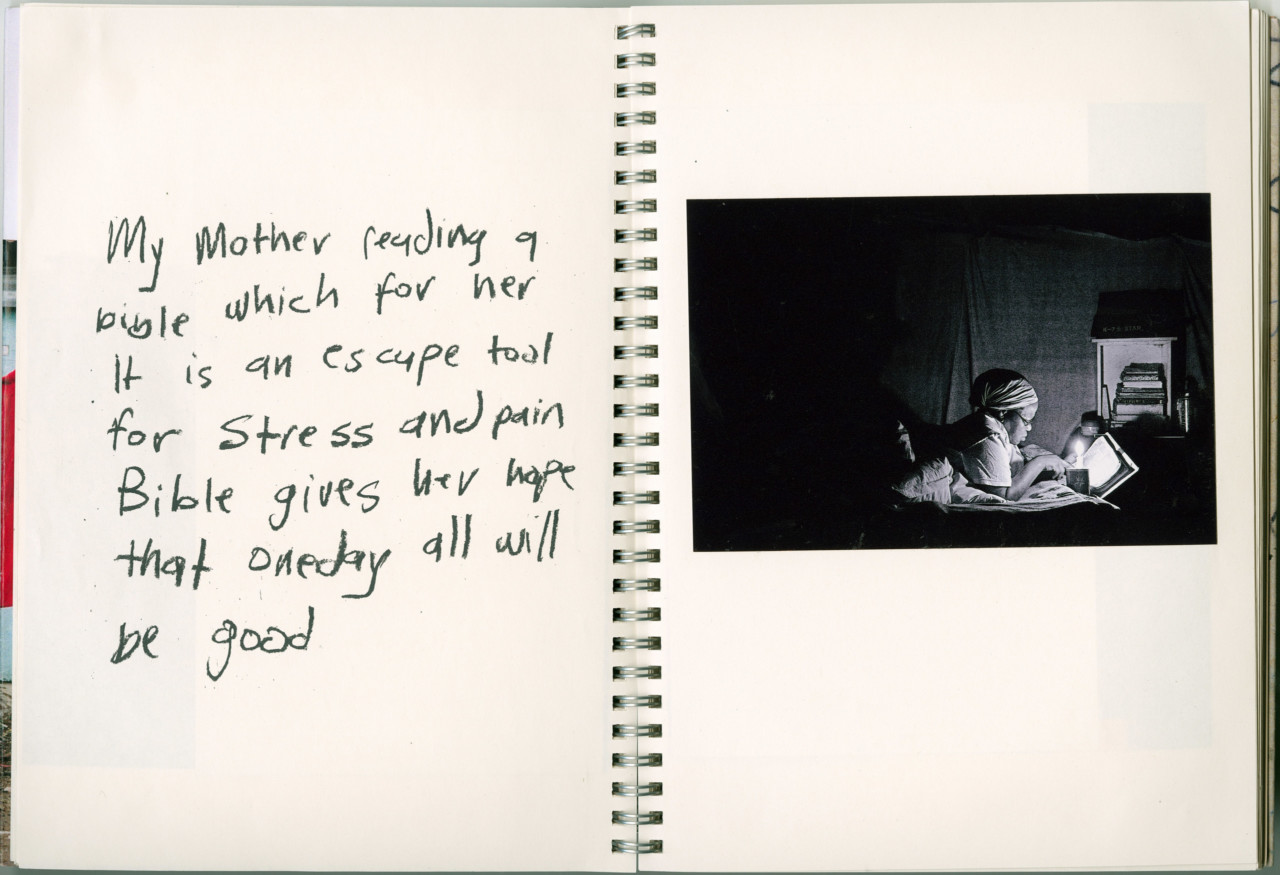

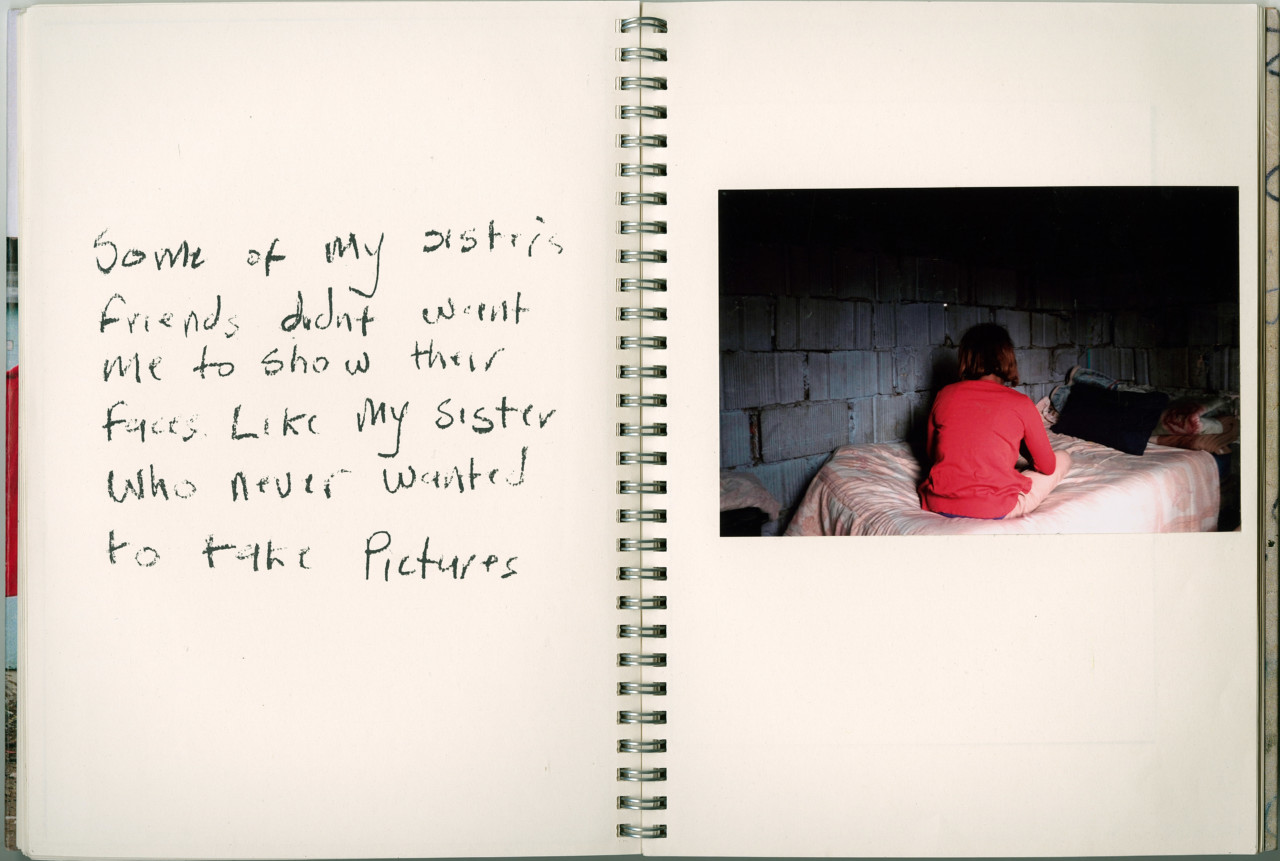

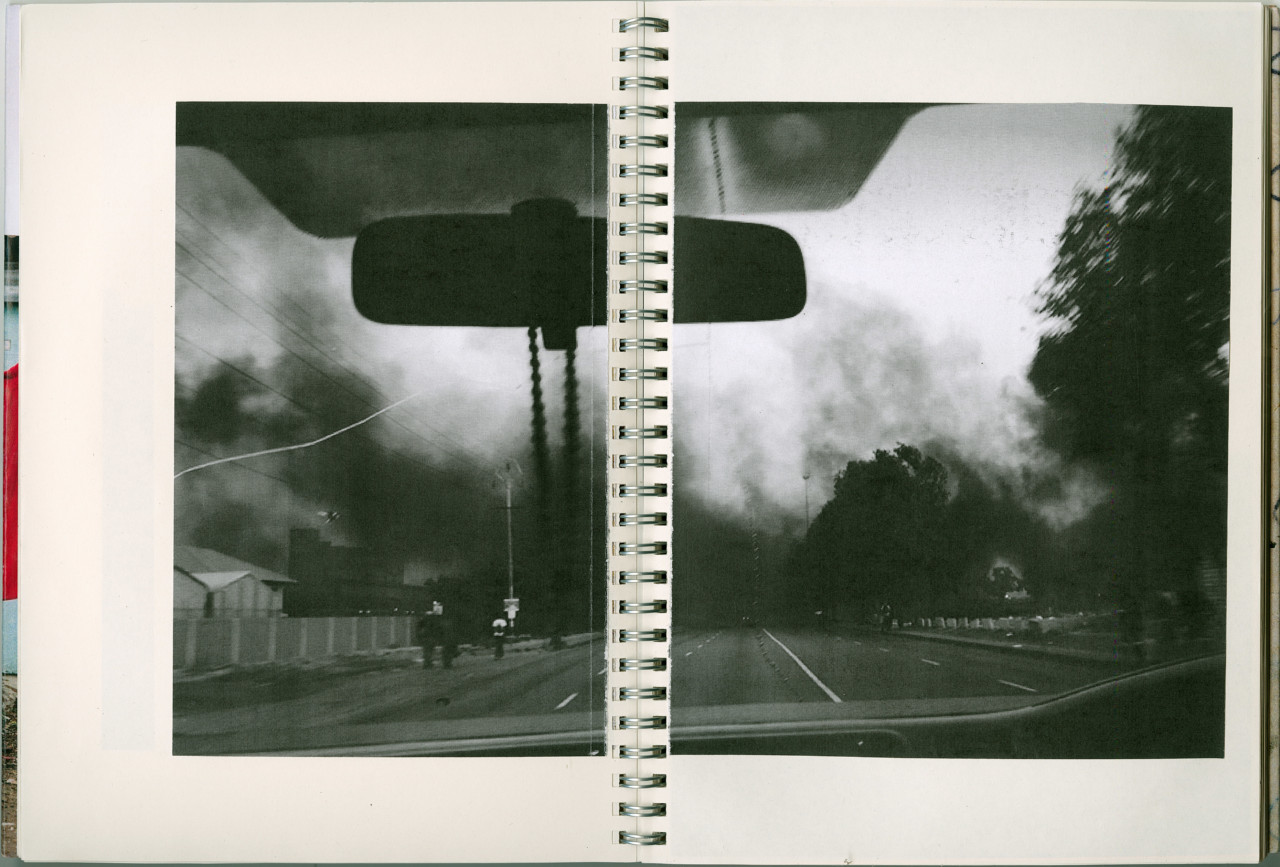

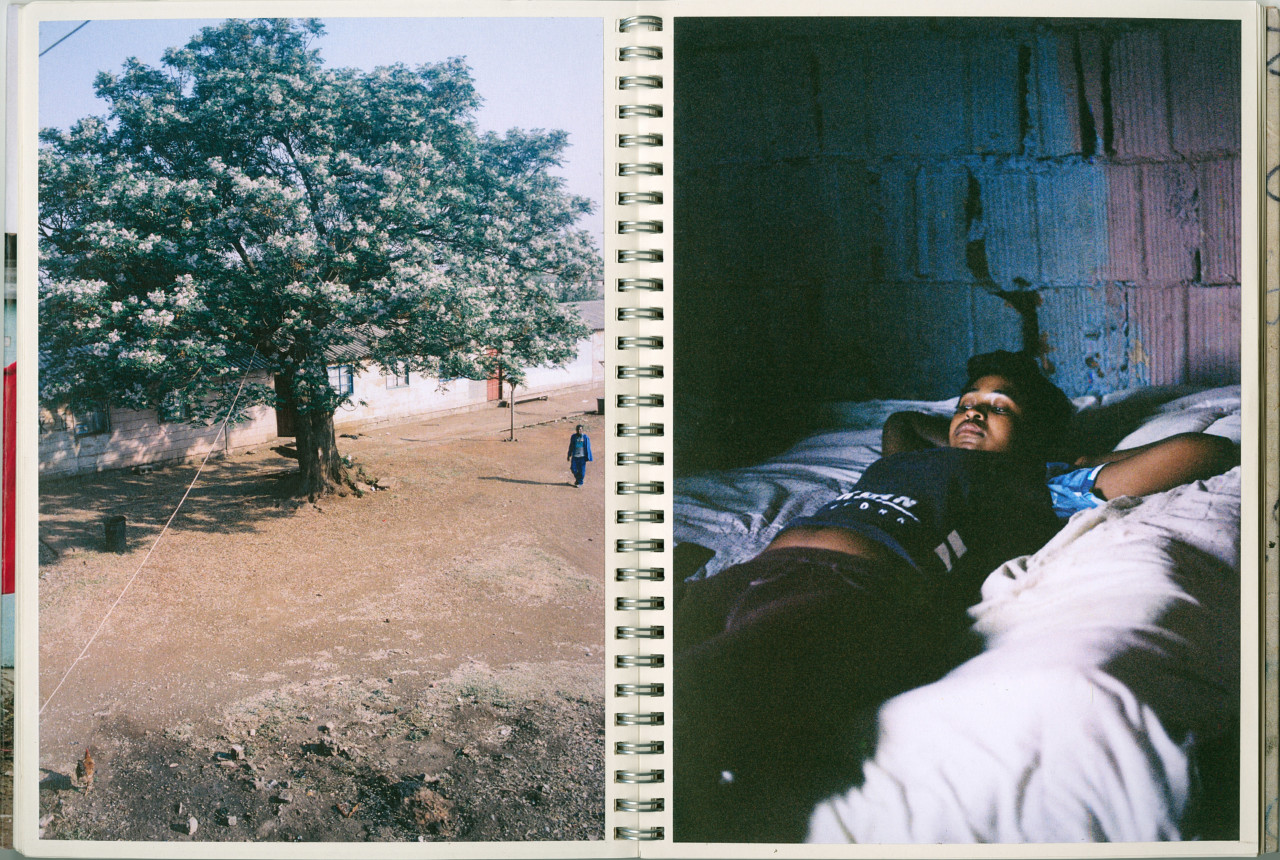

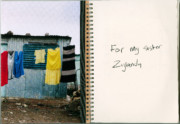

In its first form the project existed as a scrapbook, the materiality of which was important to Sobekwa. He had studied art in high school, collaging photos in his sketchbooks. Growing up, he had always had a tendency to fill his workbooks with visuals rather than writing. Sobekwa found it came naturally to him to put this project together in this way. He’d felt particularly attracted to the spiral-binding of certain sketchbooks, making prints of his photographs for a dollar each at his local print shop and pasting them in. He hand-wrote captions. The images themselves, cut in two and pieced together across many of the book’s spreads, are a fitting reflection of Sobekwa’s gradual process of coming to terms with the events. “The spiral binding talks about the fragmentation of the story. It’s disconnecting the text and images but also connecting them.” The book’s binding reminds him of traversing the various interconnected locations he visited: leafing through the book, he thinks about how one road in the township always leads to another.

The physicality of the book might also be seen as an attempt at preserving the memory of his sister in a more permanent way. The photographer says he is disappointed that he has never found writing or pictures that belonged to Ziyanda: a storm that blew through their grandmother’s house destroyed all the ephemera that belonged to his sister.

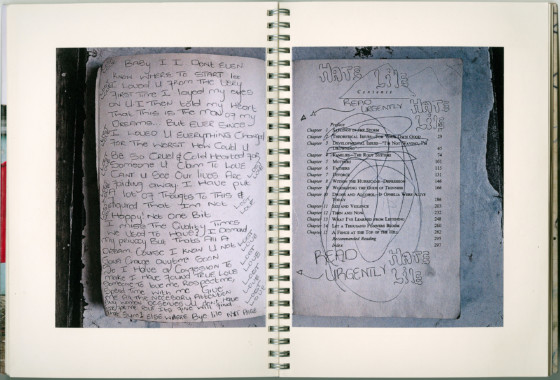

In his project, Sobekwa includes an image of the inside spread of a book belonging to one of Ziyanda’s friends whom he spoke with. During their meeting, this friend became interested in a photographic book he was carrying at the time. Sobekwa noticed that in her book, a copy of Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Lives of Adolescent Girls (a popular 1994 bestseller exploring the psychology of teenage girls in America), her own handwritten, emotive outpouring was dominating the page, overpowering the book’s actual printed text. They decided to trade books.

"You ask yourself these questions: is this a landscape she’s been in, is this Ziyanda, is it this-or-that…?"

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

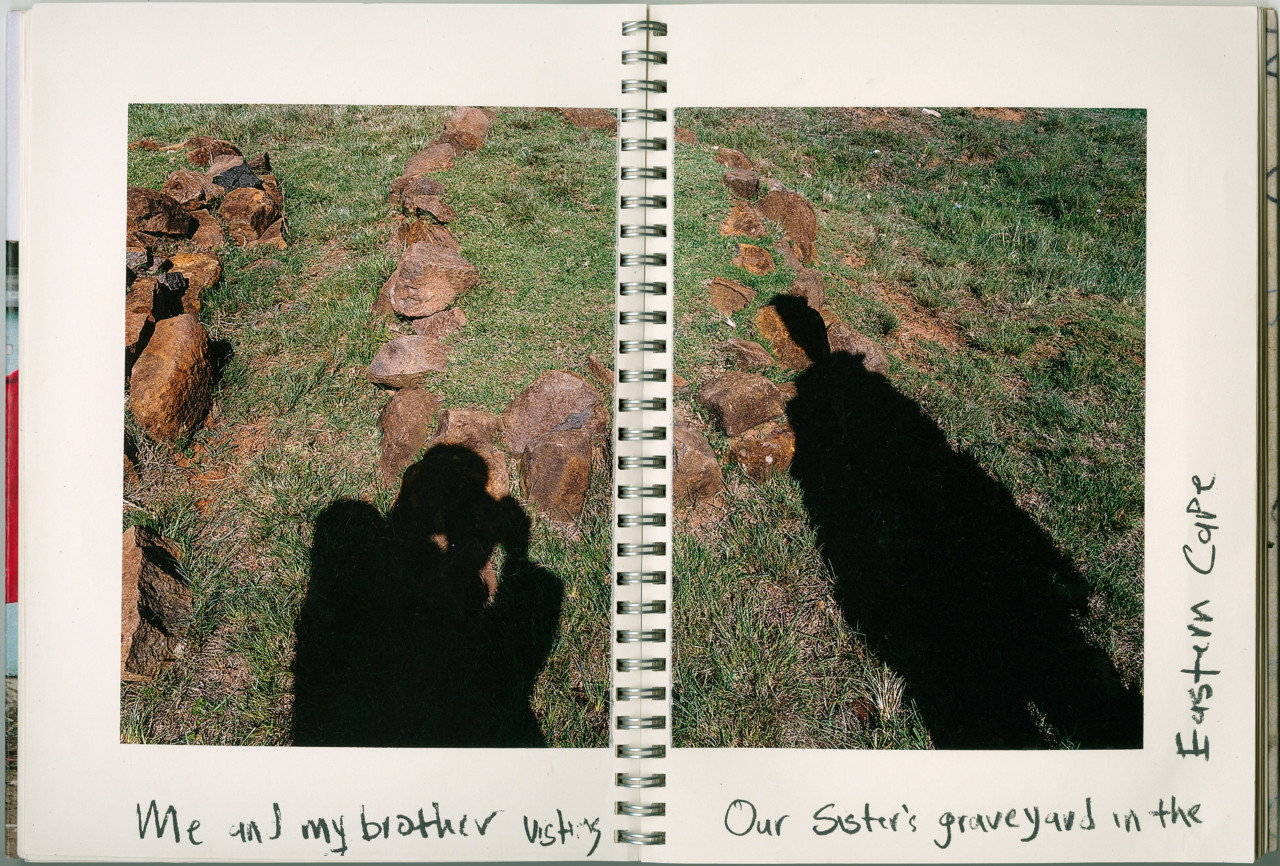

This occasion aside, written context throughout the work is very light. The photographer uses his words carefully and plainly, to compelling effect. “The text became something that worked with the images based on how I felt at the time,” says the Sobekwa. “I’m now introducing myself to the culture of writing as I’m realising the importance of it.” In one spread from the project, for example, two gangly figures cast shadows onto a mound encircled with rocks and grown over with grass. The caption reads, “Me and my brother visiting my sister’s graveyard in the Eastern Cape.”

“Some of the images are self-explanatory. Some of them are difficult to understand because they are in my home language. Because I want people to also experience the journey, sometimes you only need the image. I can’t put captions to all of them,” says the photographer, “I think that’s the beauty of this project because it invites you into this world. You ask yourself these questions: is this a landscape she’s been in, is this Ziyanda, is it this-or-that…?”

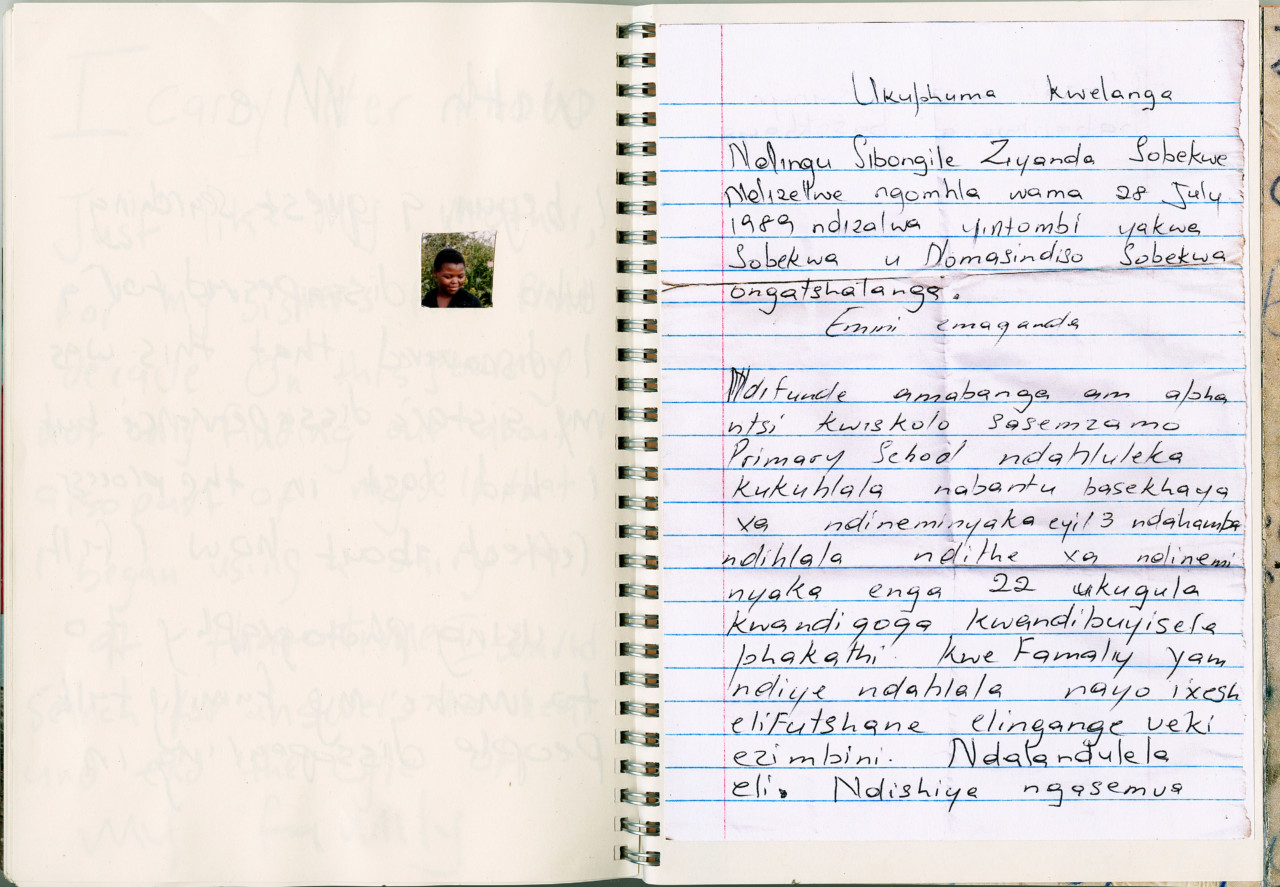

In an updated incarnation of the scrapbook, a final spread includes Ziyanda’s obituary, written in Xhosa by Sobekwa’s mother – also accompanied by the cut-out of Ziyanda’s face. The title and first line of the obituary reads ‘Sunrise… I was born Sibongile Ziyanda Sobekwa on the 28th of July’.

This project became the basis, recently, for an editioned hand-made artist’s book created for display at FotoFest in Houston, USA, in March. Sobekwa collaborated with a team of printmakers to create 42 books — one for each spread of the scrapbook. The books maintain the sketchbook’s cut-and-paste approach, preserving the directness and immediacy of the project. “The diary as a physical thing plays a very important role in talking about this journey,” the photographer says.

Recently the photographer was with his family when he took out the picture that had been the starting point for the project. “Just as it was easier for me to go to these spaces with a photograph and camera than if I’d go alone, it was easier for my family as well to talk about it when I put the photo on the table,” he says, recalling the occasion which he now sees as a profound stage in the project’s development. “I remember that as a really nice day – chilled and laughing – there were so few occasions where they spoke to me about their experiences, but this time, they were talking about their positive memories of Ziyanda. I thought maybe this was a sign that I had healed to a certain extent. […] There were tears of joy, and not tears of sadness […] I realised that some of my siblings, who were in the same position of maybe not [having grieved] enough, were full of questions about Ziyanda. I didn’t expect this to come from them, because I was the youngest.”

The photographer feels he wanted this revelation to come earlier, to have been the beginning point for the project, but acknowledges that this reversed unfolding of the process was necessary. “I think it was meant to go the way it went, how I decided to start outside my family and now I’m going inside my family. There’s other layers that come into the project to develop it.”

"I think it was meant to go the way it went, how I decided to start outside my family and now I’m going inside my family."

- Lindokuhle Sobekwa

Future steps

The photographer is still piecing elements of this story together — Sobekwa plans to make further chapters of the work, one which explores the landscape of the countryside — his grandmother’s village — where Ziyanda grew up, as well as another about his mother. Sobekwa would also like to exhibit the images in the townships surrounding Johannesburg — places quite distinct from the more internationally-recognized worlds of photo fairs and galleries. “By only releasing it online or in gallery spaces, it means you can walk away and forget about it. There can be a lack of engagement in the work when just looking and admiring it and forgetting about it the following day, when you arrive home. I also want Ziyanda to be an engagement thing.” He’s thinking about how he could show this body of work in the villages he has recently been shooting in. “The greatest education is learning from the people who I make photographs of,” he says.

The project has been transformative in many ways. “It has helped me to be okay talking about it, to talk about such things with my family, for the first time in my life. Though, a person doesn’t just heal overnight – it’s a process that I’m still in. I hope someone out there who’s looking at it can also benefit from it in some way or another.”