Woodstock, 50 Years on

Looking back at the legendary music festival of 1969, a "moment of perfect human interaction."

50 years ago today a music festival in Upstate New York changed youth culture forever, epitomised the more positive aspects of the countercultural movements of the 1960s, and created an archetype that similar events would strive to follow for decades. Here, music journalist Jeremy Allen speaks with Elliott Landy about his photographs of Woodstock ’69.

A selection of Elliott Landy’s photographs, made in Woodstock, are available as fine prints on the Magnum Shop, here.

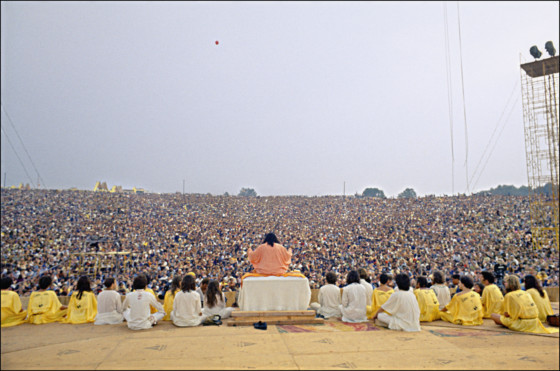

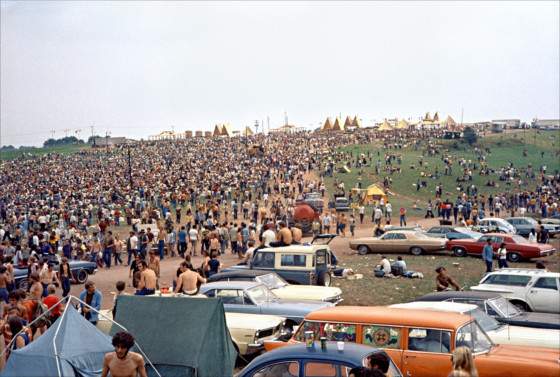

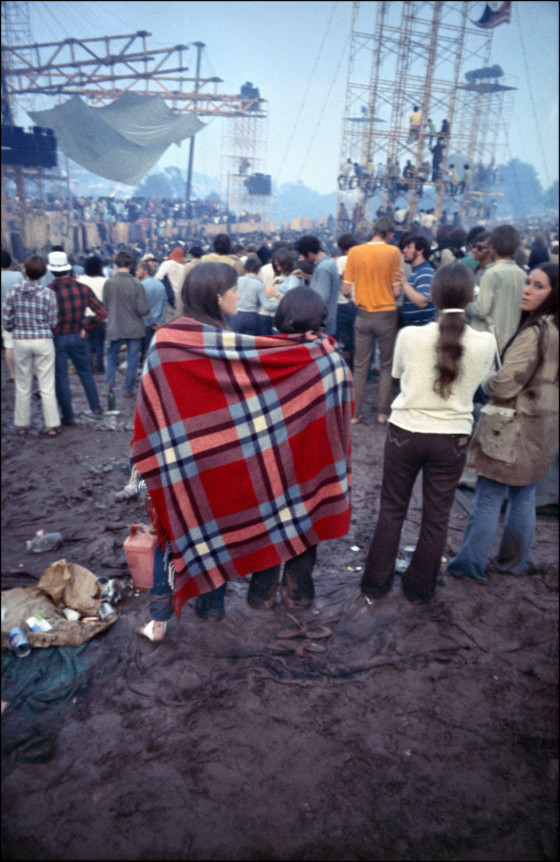

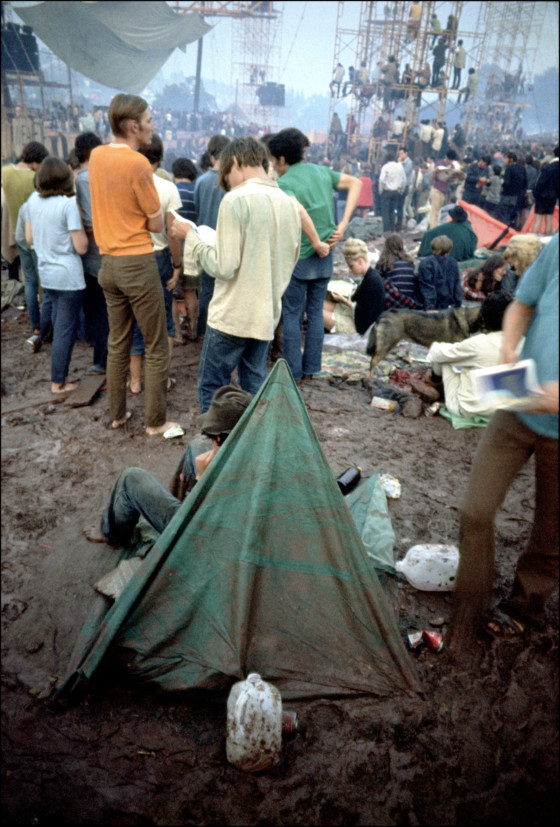

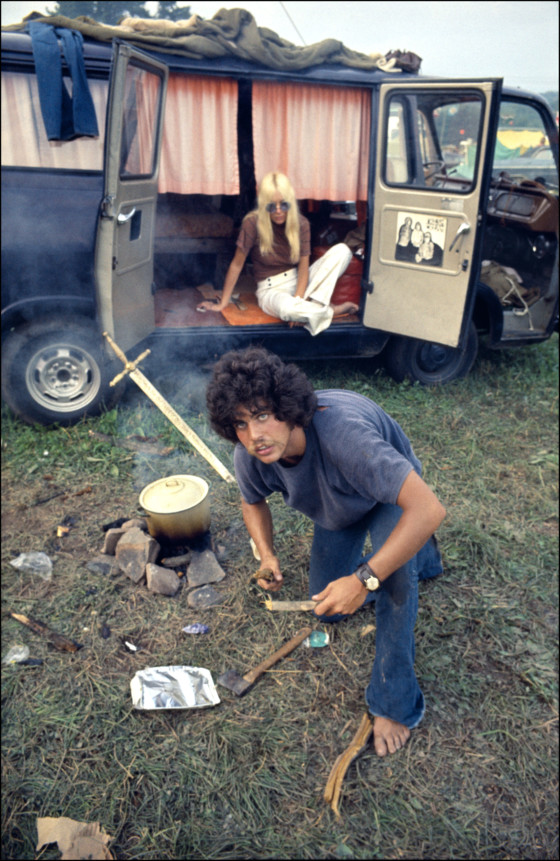

It’s 50 years since a sizable portion of America’s youth made a pilgrimage to Max Yasgur’s 60-acre dairy farm in Bethel, Upstate New York, in search of Utopia. The 1969 Woodstock Music and Art Fair retains a special place in the American psyche – and universally too for that matter – such was the unifying spirit of the collective participants. Billed somewhat grandiloquently as ‘An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music’, the Woodstock festival actually became four days of music due to a monsoon-like storm on the Sunday which led to extensive delays. The event remained almost entirely peaceful though, with no reported incidents of violence among the estimated half a million attendants. In the face of intermittent weather, mudslides and near starvation, peace and love prevailed.

Given the many disasters that almost befell the assembled that weekend, it could have gone down in history as something more akin to 2017’s Fyre Festival than the ushering in of the Age of Aquarius. Indeed, had mass electrocution across a waterlogged site because of worn out cabling occurred (which looked like a distinct possibility for a few nerve-wracking hours on Sunday afternoon), then the death toll could have made Woodstock infamous down the decades. Instead it is seen as the microcosmic exemplar of harmony, brother and sisterhood; the forebear of every subsequent triumphant musical gathering from Glastonbury to Live Aid. And yet the lack of organization, sanitation, available food, proper security or policing would be considered wholly unacceptable to a festival audience today. The precedent Woodstock set was more to do with its indomitable collective spirit than its meticulous planning; the idea more than the execution.

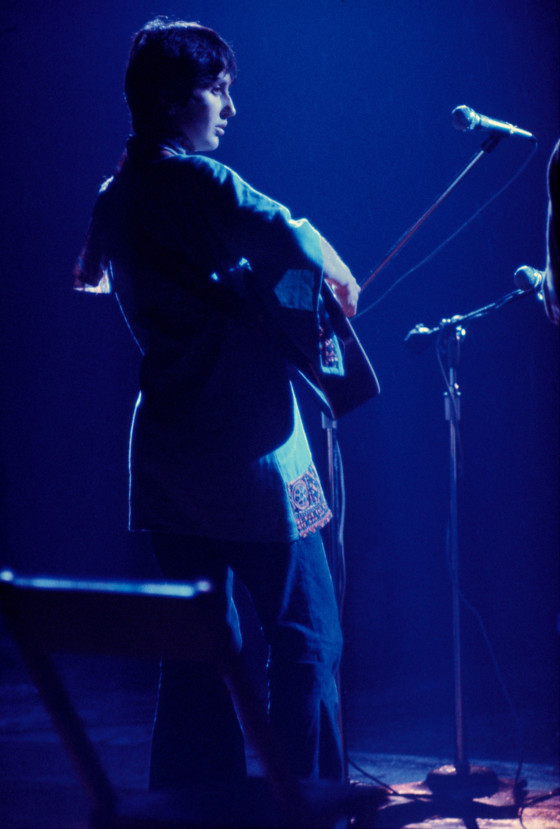

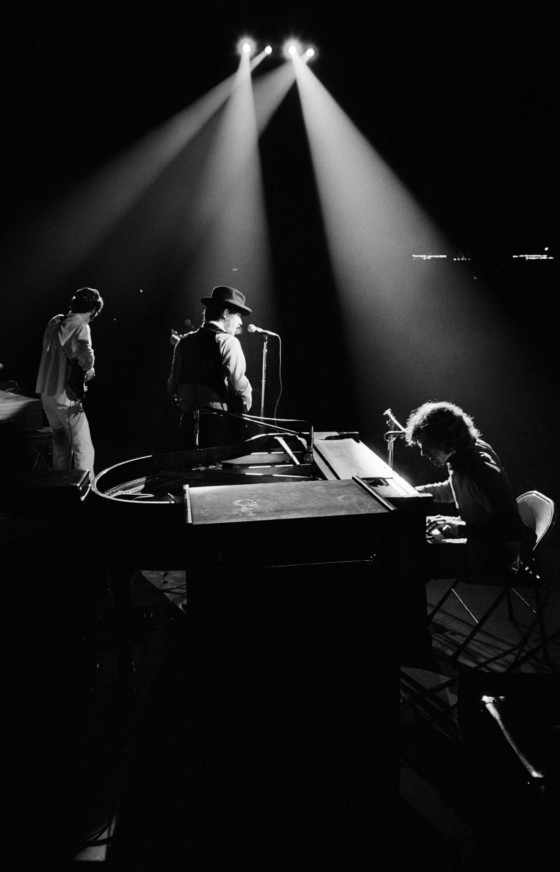

Photographer and Woodstock resident Elliott Landy, some of whose music-related archive is represented by Magnum Photos, was on hand to photograph the event of ’69 thanks to a personal invitation from promoter Michael Lang, who rode over to his house on his motorbike. Landy had made his reputation photographing The Band in their fledgling pre-fame days, and Bob Dylan when he was the most recognizable counter-culture figure on earth. “I don’t give instructions when I’m photographing musicians, and [Dylan] doesn’t like to take instructions, so I guess I was lucky that my style fitted his needs,” says Landy on the phone from Woodstock, where he still lives.

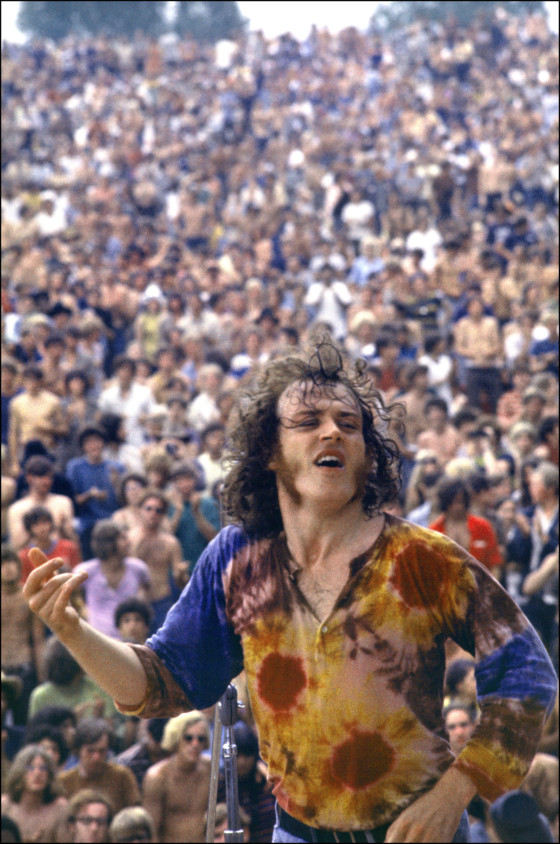

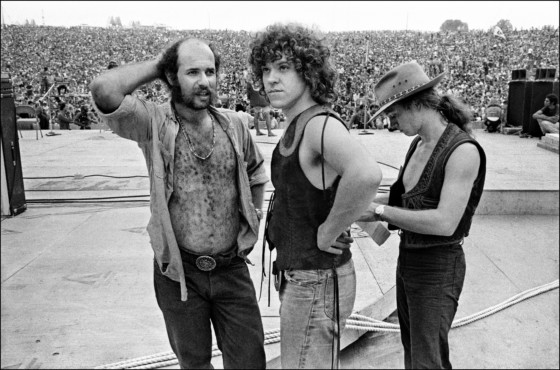

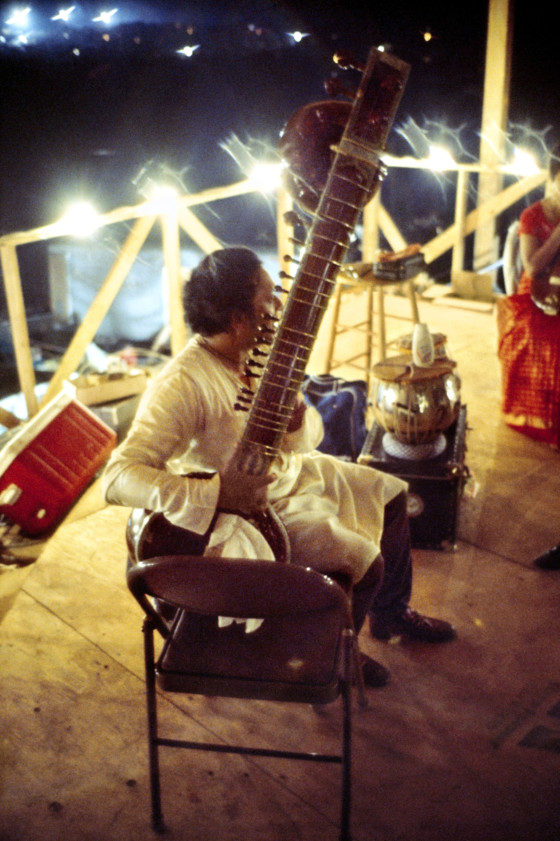

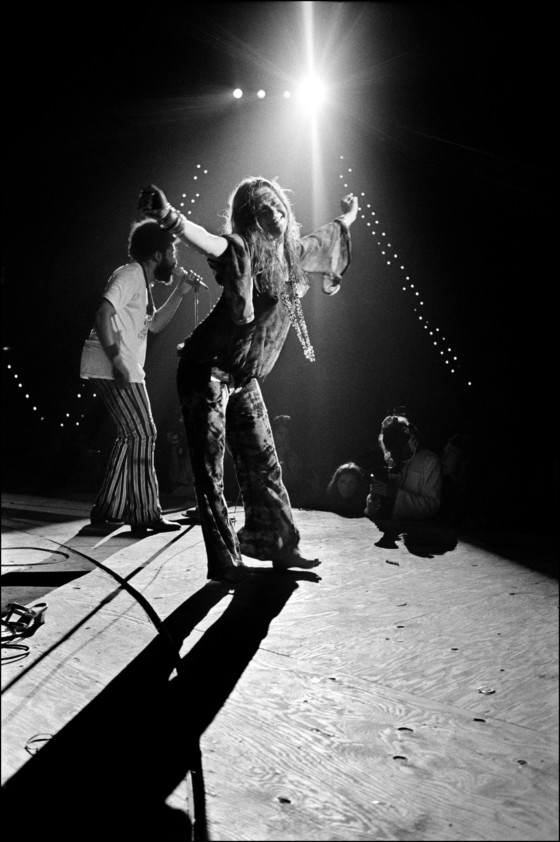

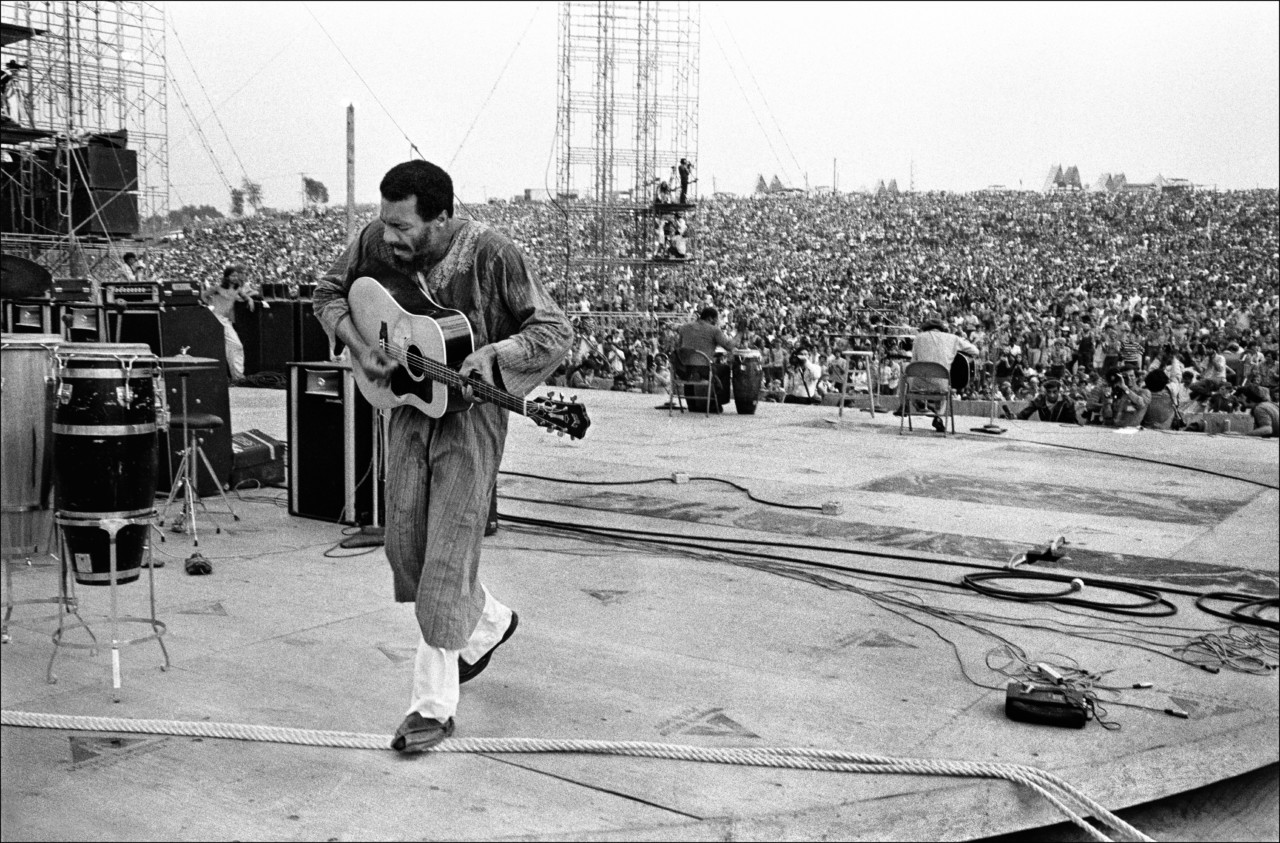

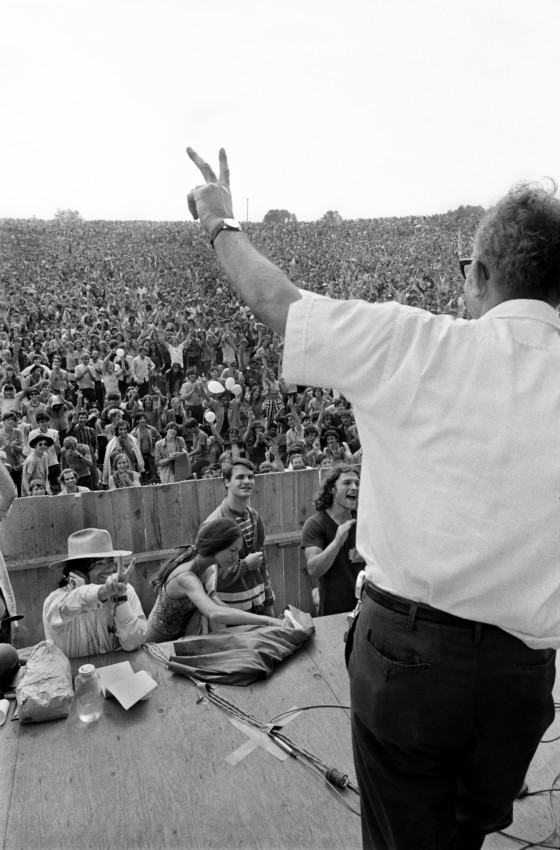

Amongst Landy’s pictures from the weekend there are the merest hints of disorder: Ravi Shankar laughing with his musicians in the rain, exemplifying a defiant, celebratory mood. Joe Cocker performing his trademark air guitar, tie-dyed, sundried, windswept and lightly soiled. John Morris, the stage announcer, grabbing a quick shave with a cutthroat razor and bucket at the side of the stage. But opener Richie Havens – shot from the back and standing majestically before the crowd, belies any of the backstage panic caused by Sweetwater being stuck in traffic (Havens was pushed to the top of the bill out of necessity).

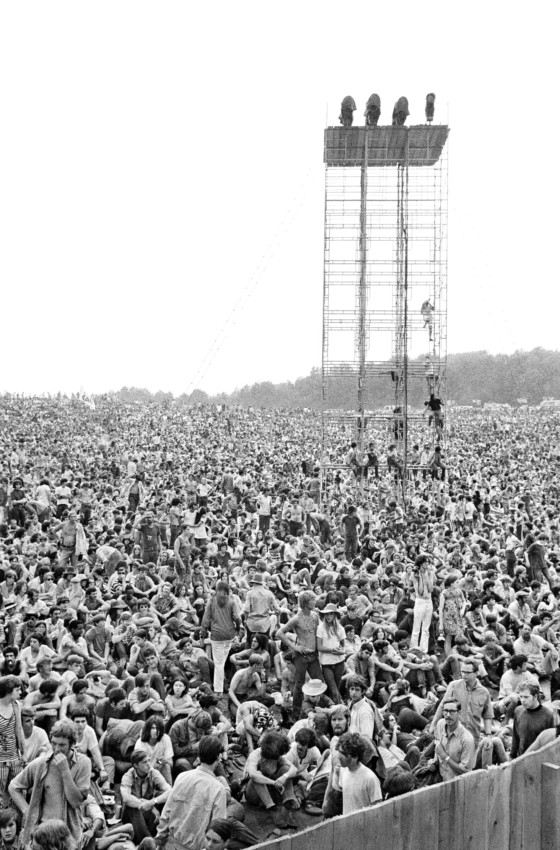

Sweetwater weren’t the only ones stuck in traffic. Authorities were initially notified that 50,000 ticket holders would attend when – in reality – a figure closer to 186,000 tickets had been sold in advance, and nearly three times that number made it with many thousands stuck in traffic on motorways. The situation worsened when hopeful attendees started to abandon their vehicles where they stood to continue by foot to the farm.

Max B. Yasgur’s Hog Farm in White Lake was actually about 60 miles south of Woodstock, with the festival forced to relocate at the last minute due to licensing issues. The main financiers, John Roberts and Joel Rosenman, were faced with an impossible choice between the stage being erected or a sturdy perimeter fence being put up to keep non-paying patrons out. With the entertainment clearly a priority, the makeshift fence had to be swiftly dispensed with for safety reasons when hippies started clambering over it days before the event was due to begin. It essentially became a free festival from then on in.

“Joel Rosenman and John Roberts don’t often get enough credit for this,” explains Landy, “But they were very careful. They knew what would happen if they stopped doing the right thing. If they said, ‘Well gee, I’m not making money, why should I do anything here?’ then there would have been riots and there would have been danger.”

"The cultural legacy of Woodstock and the reason people are still fascinated with it is that it is possible to have people living peacefully together in difficult situations"

- Elliott Landy

Despite all the ineptitude and drug use, the gathering has passed into legend. 1969 represented the pinnacle of human achievement: man walked on the Moon, supersonic speeds were achieved by Concorde, and there was a collective sense that world peace could be achieved despite a war raging in Vietnam. “The cultural legacy of Woodstock and the reason people are still fascinated with it is that it is possible to have people living peacefully together in difficult situations,” says Landy. “And it was a moment of perfect human interaction where everybody there was caring about everybody else to a greater or lesser degree.”

"There was an awareness that things needed to change. At Woodstock those ideas took root."

- Elliott Landy

For many, the hippy dream died four months later at the Altamont Free Concert in California which was marred by considerable violence and three deaths, as the sixties passed into the seventies. For all the retrospective ‘end of an era’ thought pieces, Landy doesn’t regard Woodstock as the final hoorah of the peace movement. “No, it was absolutely the start of something,” he says. “The environmental movement, the women’s movement, universal healthcare, renewable energy sources… there was an awareness that things needed to change. At Woodstock those ideas took root.”

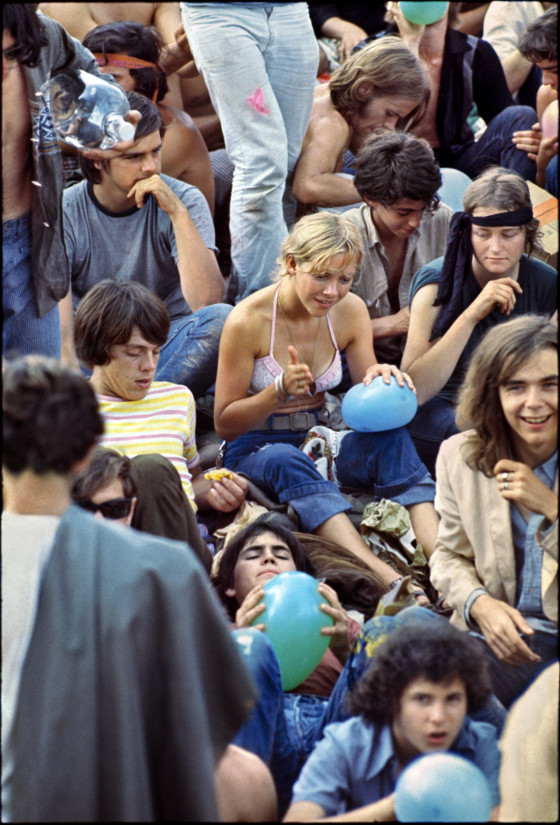

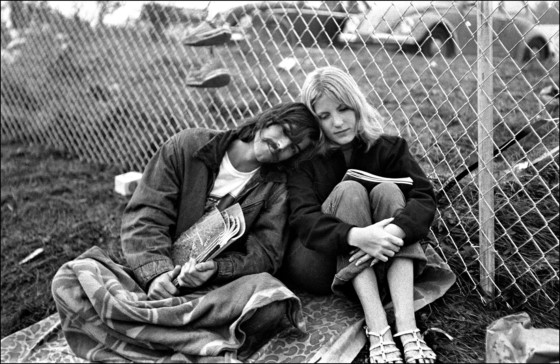

Given the collective spirit, it’s no surprise that the crowd scenes are as mesmeric as the pictures of performers, either onstage or backstage. Landy’s favorite picture features attendees huddled together, yet concentrating in their own spaces, a moment that is illustrative of the wider purpose of the gathering:

“There’s a blonde girl in the center of the picture who is holding a balloon, and she’s caressing the balloon very gently, and the people around her are all into their own thing. She’s barefoot, she’s got jeans on, blonde mid-western hair, so she’s an average American. She’s obviously stoned and she’s grooving on the music, and the people around her are all into their own thing… nobody is bothering her. They’re all sitting close together but everyone is in their own space. The guy next to her is grooving on his balloon that’s popped. He’s not upset by it, he’s puzzled by it. And the guy below the girl is lying on his back and grooving on his balloon also. So this is what Woodstock was about. It allowed people to get into themselves and also be part of the crowd at the same time.”

"My photographs are intimate because I can see people without judging them"

- Elliott Landy

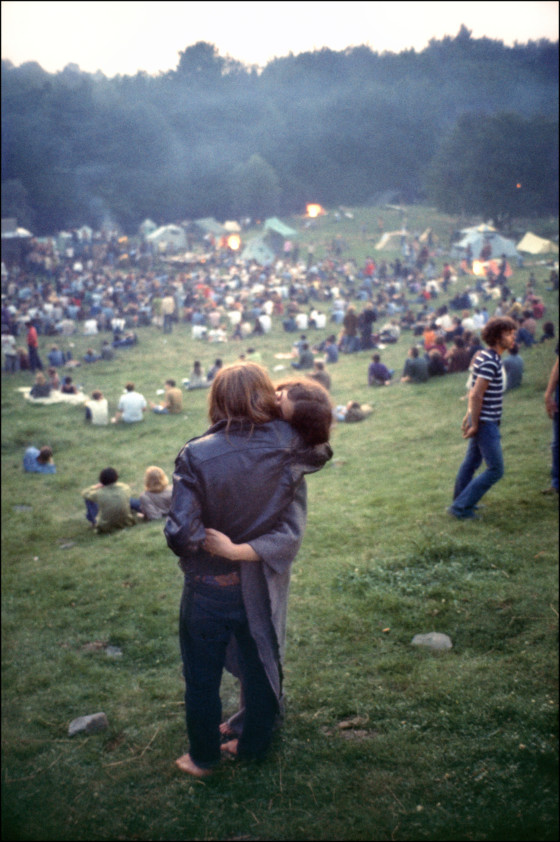

Another beautifully-timed shot of two people kissing is Doisneau-esque, though the glamour of Paris is eschewed for the mise-en-scene of a rolling field and mud. Whether it’s a striking shot of Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick backstage, or a pregnant Joan Baez elegant before the throng, Landy’s shots portray a sense of intimacy that is at odds with the situation. There are also some candid pictures of Janis Joplin drinking and laughing backstage, which perhaps take on an added poignancy given that she would die just 14 months later from an overdose. “My photographs are intimate because I can see people without judging them,” suggests Landy. “I’m just taking the picture without getting in the way.”

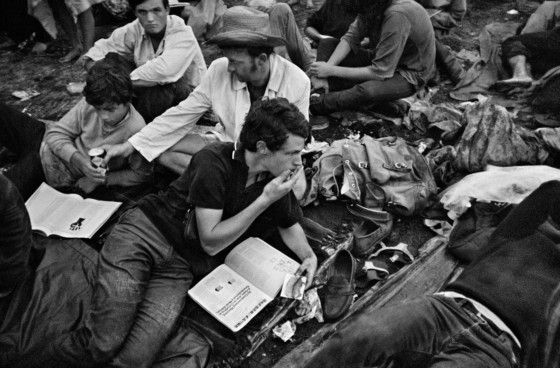

Landy took a Japanese Widelux camera offering 140° coverage for panoramic vistas along to Woodstock, and he admits it was the only time he ever found a use for it during his distinguished career. Panoramic shots are easily achievable with a mobile phone nowadays, but they were rarer in 1969. As well as sweeping crowds, Landy also instigated a happy accident when he was hiding under the stage taking shelter from the storm. He unintentionally hit the shutter on the Widelux, a serendipitous moment of which there have been many in his life, and one that he says demonstrates how his generation looked differently at the world than the current one:

“You can see the steps going up to the stage, but if you look off to the right, you can also see the rainstorm and the crowd of Woodstock. I had full stage access so I went under the stage. I didn’t want my camera to get ruined. I didn’t have any rain gear. So here I am under the stage at Woodstock, and I didn’t even think to take a selfie! That’s the difference between today and that world: everything today is an extension of yourself; ‘let me share who I am with everybody’. Back then it was only really about documenting the outer world and sharing the love.”