Living with the Land: Capturing a Disappearing Culture

Magnum photographer David Hurn reflects on the more than 40 years he has spent documenting the changing face of rural Wales

As part of an ongoing series, Living With the Land, we speak to Magnum photographers whose work explores a way of life tied closely to the land and rituals of nature

Culture is influenced by the terrain and the weather. So summarised the eminent Marxist critic Raymond Williams, while in conversation with photographer David Hurn. When Williams was still alive, the two Welshmen would discuss at length the complexities of what made up a ‘culture’ and it was concluded, “in very simple terms”, that those two elements were hugely significant.

When Hurn returned to Wales, in the early 1970s, it was with this theory in mind. He set about exploring what defined this rainy, mountainous country. Inevitably, landscape and agriculture became a central focus in the project. “We only have a couple of reasonably large cities so, by and large, if you travel around Wales you see open space,” says Hurn.

Indeed of the core industries that the country once relied on—steel, slate, coal and agriculture—only agriculture remains intact. “Part of the Welshness of Wales is the farmers. I like farmers—they are warm and open. They work their butts off and I like people who work hard.” the photographer explains, adding that the land and agricutlure are, “a major part of Welsh life.”

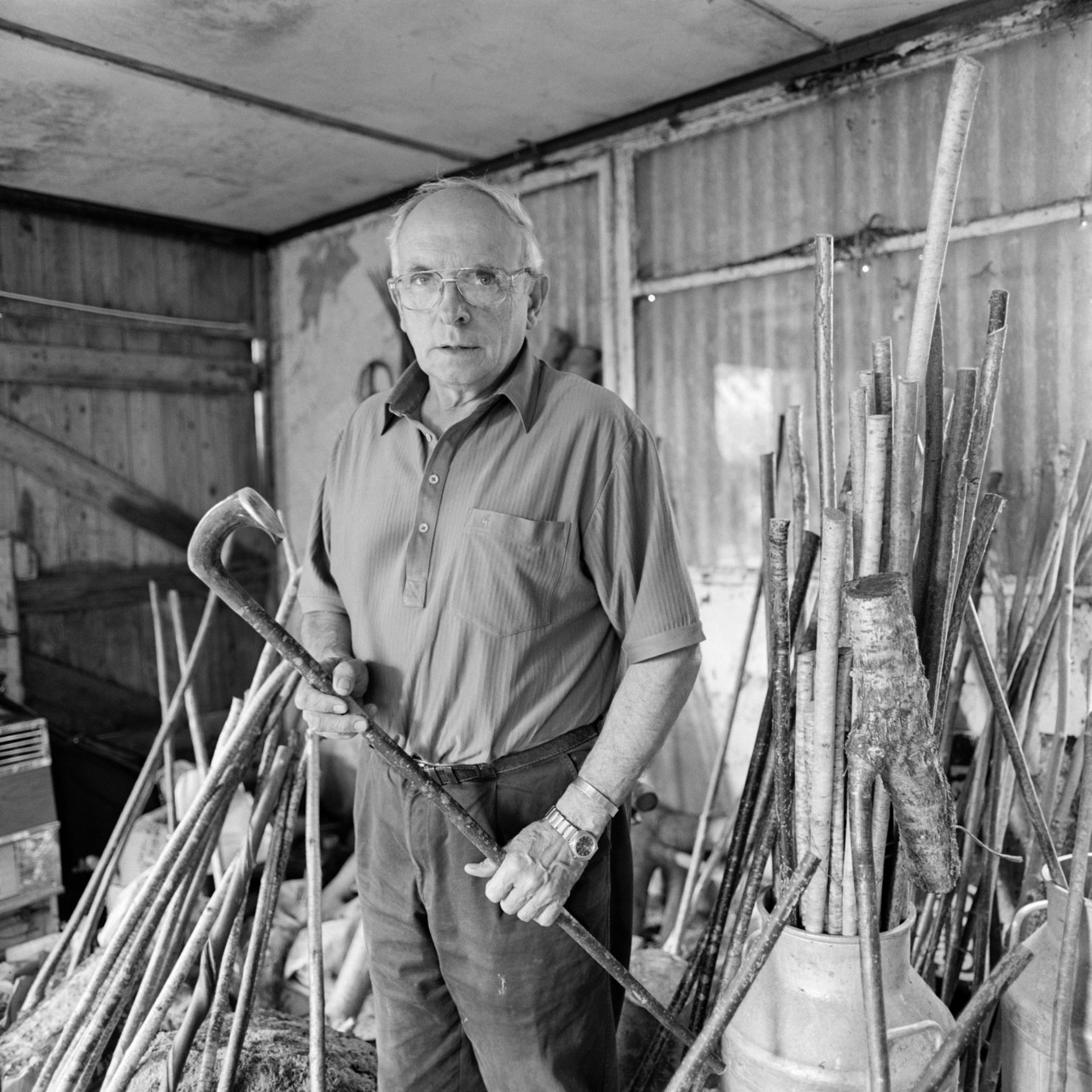

As with all of Hurn’s projects, he did not set about capturing rural life in his homeland with any kind of agenda in mind. “I photograph what interests me,” he says. This approach has led him to document everything from sheep-shearing to sheepdog trials, and champion stick-makers.

“There is a strong sense of community, and it’s all part of it,” he says. “For example, on the Young Farmers Day when they do these silly seeming things like tug-of-war and all that kind of stuff – it’s still very much part of that farming community. Indeed the social side for young farmers is virtually as important as getting in the mud and digging up the potatoes.”

Hurn, who has himself lived in rural Wales for the past 40 years, has seen drastic change in all areas of Welsh life. In his village of Tintern, he has noticed a decrease in residents working in forestry, for example, alongside a growing abundance of university deans. “It’s becoming a little yuppified,” he concludes. Unfortunately, sometimes with change comes eradication.

Much of what Hurn has documented over the years has now disappeared or is disappearing, inasmuch he sees his work primarily as producing an historical record. “I have pictures of sheep washing for example, where they used to drive the sheep into a pool with chemicals in it and so on. That’s no longer done,” he says. “So the pictures that I have of the practice are now historic.”

Farming in general is “exceptionally vulnerable” to change, even moreso today due to looming Brexit. Hurn worries that if Wales’ agricultural life goes the same way as heavy industry, the nation’s very culture will be thrown further into flux. “My feeling, talking to the sheep farmers, is they’re going to all have to be tourist bed and breakfasts sooner or later,” Hurn adds. “And if you take away heavy industry, if you take away sheep farming, then you’ve decimated the very identity of a particular grouping of people.”