Internat

Carolyn Drake discusses returning to a Ukrainian orphanage and working with a new approach eight years later

Carolyn Drake first visited the remote, ex-Soviet girls orphanage that is at the centre of her new project Internat while living in Ukraine in 2006. Having been granted a Fulbright fellowship right after finishing her degree, Drake spent a year studying changing notions of gender in the country. “I had read about a backlash against Soviet ideas of gender equality and a resurgence of feminine ideals,” she remembers. “I saw it as a chance to step out of my own frame of reference, and a way to continue looking at the malleability and impermanence of beliefs.”

Drake was pointed toward the women’s facility after having spent the night at another orphanage nearby. “I took a walk to the edge of the neighbourhood, and there in the forest was the Internat, a building full of girls who had been placed there because they weren’t considered normal.”

The Internat – or Petrykhiv Children’s Home as its translated name reads – is a secluded estate that sits on the outskirts of the city of Ternopil, on the banks of the Seret river. Large and looming, a thick stone wall skirts its boundaries. On the inside, an all-female staff of nannies and nurses in white uniforms walk shadowy hallways seared with shafts of light from dusty windows. One male director oversees proceedings. “Seventy women, reportedly ill, none older than thirty-five, reside within its boundaries,” reads the text of her self-published book.

"I felt like this blending of authorship gave the work more depth and shifted the meaning"

- Carolyn Drake

In the same vein as several institutions like it across the country, the Internat was designed to provide shelter for girls deemed disabled – a particularly regressive act in comparison to much of the rest of the world, where resources are increasingly being aimed at integrating people with disabilities into society, instead of withdrawing or isolating them from it. Drake met and photographed the group of young girls institutionalised there at the time, and shortly after left without returning for almost another decade.

In the years that followed, Drake went on to complete two major bodies of work. Over the course of five years she shot Two Rivers, an expansive photographic record of people, stories and landscapes made while travelling the main waterways of Central Asia, and Wild Pigeon, in which she immersed herself into the communities of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. Seeking to bring the people she was documenting into her creative process as active collaborators, Drake travelled with a box of scissors and pens, asking people she encountered along the way to draw upon and reassemble the images she had taken. “I felt like this blending of authorship gave the work more depth and shifted the meaning,” she says, “highlighting the intersection of our viewpoints rather than a single authoritative voice.”

Having begun to wonder what became of the girls she had photographed in the Internat, Drake returned there in 2014, and found that most of them were still there, adult women by then. This time, she had ideas of collaboration in mind. “In Wild Pigeon, I had invited people to collaborate after making the pictures. In this series, it seemed to make more sense to involve the women in the process of making them.”

In their cloistered existence, Drake became interested in how the women, “sculpt their own ideas of femaleness from the limited interactions and sources to the outside world they have.” Developing in a world entirely without the presence of men, the women had shaped and moulded their identities, and their ideas of what it means to be a woman, from the hodgepodge of fantastical imagery they had before them – from fairytales and fables, religious imagery, soap operas, old storybooks and myths.

"Nature, real-life activities, and the thick walls surrounding the facility became vehicles for exploring questions about control"

- Carolyn Drake

In front of Drake’s camera and with her encouragement, the girls played out their own fictions and fantasies, and embodied characters pulled from her own subconscious too. “When not occupied by daily chores, they play the roles of mother, daughter, queen, wolf, monster, and pixie,” the text in her book continues, and fantasy is crafted out of the sense of imagination she found there. In this space as a backdrop for her photographs, “nature, real-life activities, and the thick walls surrounding the facility became vehicles for exploring questions about control, the imagination, and the construction of normal female behaviour.”

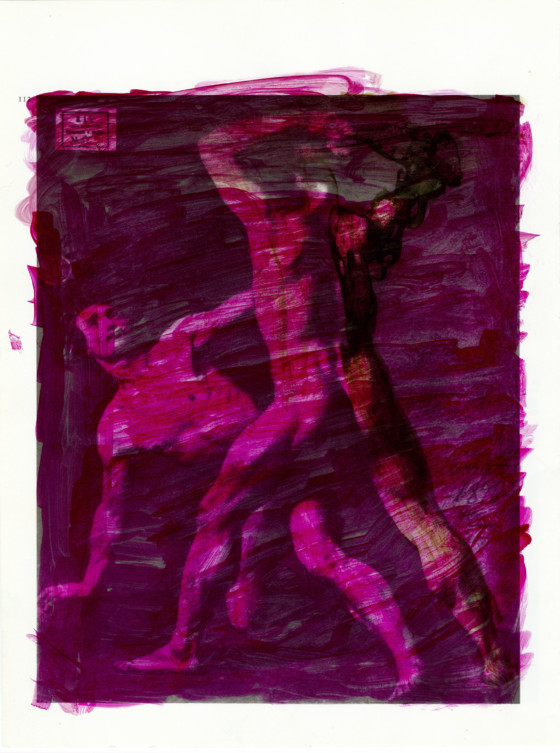

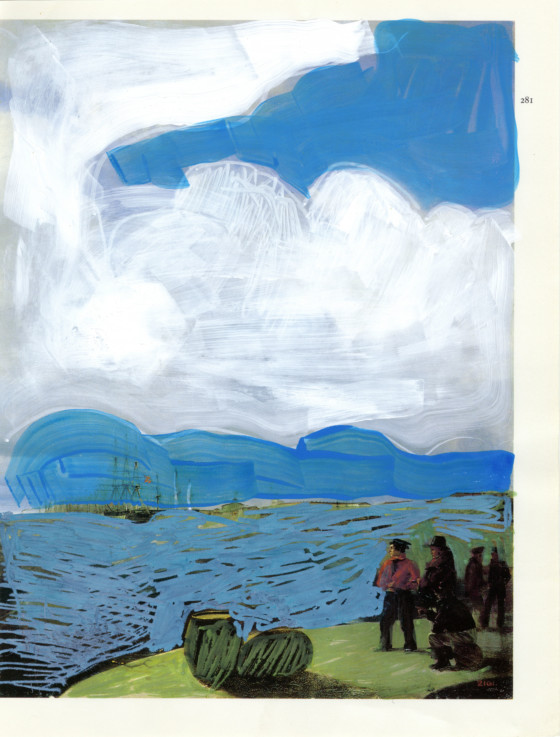

The images in Internat are expressive and sculptural, performative and painterly. We see the women make brooms out of bundles of sticks, tend to vegetable gardens, weave their hands through ribbons to create star shapes, kneel in brightly coloured clothes to gather flowers, drape tinsel over themselves, and contort their bodies against the light to cast shadowy forms across the walls. Often, the women’s faces are obscured; painted over, covered with props or turned away from the lens, in some ways perpetuating their myth.

During the times Drake was restricted from photographing – which were frequent – she sought out other ways to collaborate with the women outside of taking pictures. In a local bookshop, she came across a book about the 19th century Ukrainian artist, serf, poet and imprisoned political figure Taras Shevchenko. She took the book apart, and invited the women to paint upon its imagery. In colourful swathes and swirls of paint they affected the pictures, reimagining the scenes of history before them. “In doing so,” Drake says, “they became artists, creators, ethnographers, and designers themselves.”

One of Drake’s biggest challenges was upending the rigidity of the women’s prescribed daily routine. “Between regularly scheduled meals, there are chores, and during their spare time the women normally embroider over patterns or watch TV,” Drake explains. “I quickly saw that my visits interrupted the routine, so I decided to push that further. Each day, I came in with a few ideas about how we could use this environment that the women were bound to, as a stage for imagining something beyond it.

"I wanted to work toward upsetting that standard"

- Carolyn Drake

The plans I arrived with inevitably turned into something different once the women got in front of the camera.” Drake’s presence, and her process, introduced a feeling of uncertainty, as well as a curiosity, about what is ‘normal’ and what isn’t, and the fluidity of the roles of author and subject were subverted. “As someone working in photography, a medium that’s often associated with precision and truthfulness, that was interesting to me,” Drake explains. “I wanted to work toward upsetting that standard.”

At the age of 35 women are no longer allowed to stay at the Internat. Having spent the majority of their lives there, many are moved straight to geriatric wards, their lives spliced neatly into two; girlhood and old age. Drake’s images of this tiny commune oscillate between a poignant sense of sisterhood and a profound solitude too. On the question of a preference between telling stories as an objective observer, or inviting a greater level of collaboration, Drake maintains that either can work, given that most people carry a set of ethics with them about how to interact with other people in a respectful way. How to inhabit the lives of others in images has long been an ethical conundrum for photographers. “Right now, I’m more interested in exchanging than in controlling, and I’m more interested in having a dialogue than in lecturing, so moving toward collaboration was a way to align my work better with my current interests.”