Wild Pigeon

Carolyn Drake reveals the thinking behind her collaborations with Uyghurs in China

Between 2007 and 2013, Carolyn Drake traveled in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, a remote province of China, 2,000 miles from Beijing, staying in Uyghur villages and cities on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. The Uyghurs are a predominantly muslim Turkic people, one of China’s recognised ethnic minorities, with their own distinct language and writing systems. She found that the landscape changed on each visit as historic Uyghur neighborhoods were being torn down and rebuilt as modern Chinese cities, a result of government development policy.

As Drake tried to ask Uyghurs about these changes, the translator she was using quit, saying her questions were “too political”. So instead, she invited people to communicate through drawing. The resultant body of work is titled ‘Wild Pigeon’, so named after a folk tale about a bird that would rather die than be caged by humans, a story banned from publication by the Chinese government but passed on by word of mouth.

As this work is on show as SFMOMA, Carolyn Drake discusses the evolution of the project and reflects on the problems that arise from authoring stories about other people’s lives.

Wild Pigeon is a project that began for me in 2007, around the time I moved to Istanbul. While I was based there for six years, I made friends with a lot of Turkish artists, some of whom were critical of the Orientalist image-making they felt had persisted into the 21st century – European and American photographers passing through, even stopping to live for a period, and making a living by getting to know and define Turkey, the Middle East, and Asia for audiences in their own countries.

I’d been working in the far western part of China, an area that was part of the Great Game at the end of the 19th century, when Russia and Britain were competing to map and document and send military personnel to an area they saw as up for grabs. I was working in a sort-of lyrical documentary mode, and as I looked back over my pictures, I saw metaphors in some of the images, but I still struggled to situate myself outside the legacy of these colonial paradigms in which ‘Westerners’ were image-makers defining the ‘Other’.

I could explain through my pictures that Uyghur people speak a Turkish language, practice Islam, grow food in the desert, and trade across the borders, but I felt these kind of pictures basically fed the idea that Uyghurs were part of a culture waiting to be developed, and I stopped feeling I could justify that approach, so I had the choice of either going home and focusing on “what I already knew,” or finding a way to make the work more collaborative, and more conscious of photo documentation as a medium of control.

While I was processing these ideas, there was also an incredible amount of change happening in Xinjiang and I watched the landscape transform from a Uyghur place into a Chinese one, as the government took a tighter grip on its Muslim borderland.

The government was sending waves of Han Chinese migrants into the province, tearing down Uyghur neighborhoods and rebuilding them in a way that allowed for more control and surveillance. There were subtler changes happening too: the Uyghur language was being replaced with Mandarin Chinese in schools, government loyalists were appointed as imams in mosques, and all kinds of Uyghur-centered places were being shut down, including a disco which was gone when I returned two years later.

" I watched the landscape transform from a Uyghur place into a Chinese one, as the government took a tighter grip on its Muslim borderland"

- Carolyn Drake

Looking at all the change confirmed what I already knew, which was that trying to define the essence of a culture is futile – identities are always in flux, always being negotiated. I wanted to see if I could start using photography to engage in a dialogue and step away from the idea of documentation. I started with the obvious – switching to an audio recorder. I went with some prints to this new neighborhood for people whose homes had been demolished and asked my translator to ask a woman I had photographed why she had moved there. The translator quit on the spot, telling me it was too dangerous for him, and that there was a prohibition against Uyghurs having this kind of a dialogue with foreigners.

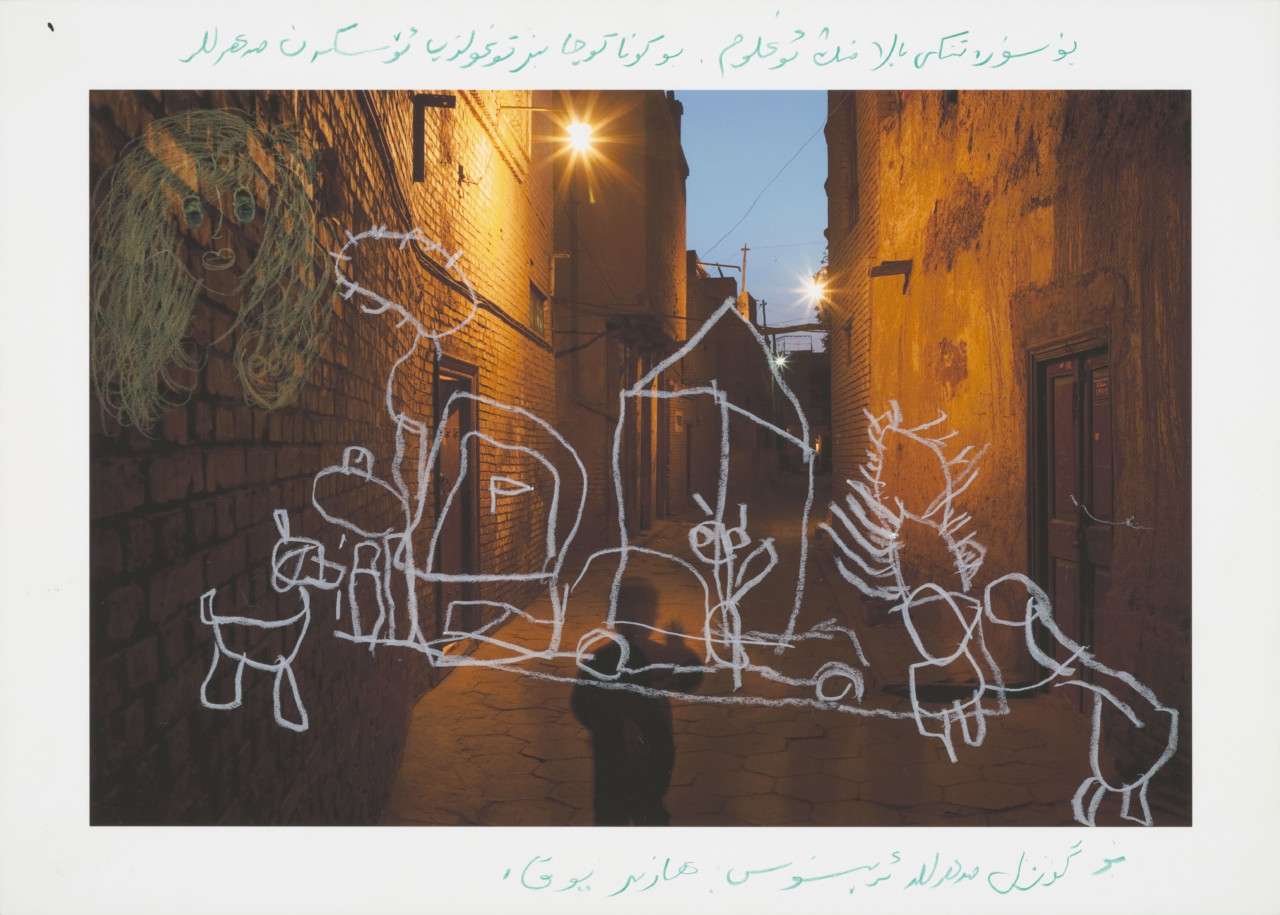

So I decided to try a less confrontational/threatening way to work with people: I brought prints and invited people to draw over them, thinking that maybe we could have a covert conversation through images.

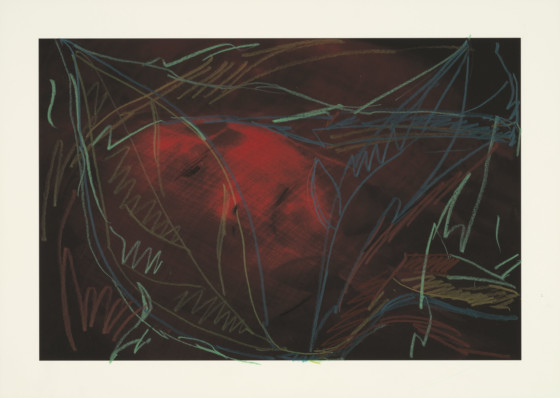

During the Kurban festival, part of the Muslim holiday of Eid, I made pictures as a family I knew slaughtered a camel. When I brought back the picture later, one of the family wrote in Uyghur language around his profile a phrase that translates to something like: “A person only lives once, you can’t forget loyalty and faithfulness in this lifetime.” I spent a long time trying to understand what that meant. It was a turning point where I started to be less interested in finding an exact translation than I was in the gaps in understanding – where translation falls short.

"I brought prints and invited people to draw over them, thinking that maybe we could have a covert conversation through images"

- Carolyn Drake

On the back of my book Wild Pigeon, I printed an excerpt from a conversation I recorded with an older man. We were getting reacquainted, and I told him how fond I was of the music he played last time I visited, how his music really stuck in my memory. He proceeded to explain to the other people in the room that the word music means all of the Uyghur instruments, including the dap and the duttar and the rawap, and the sounds that those instruments make. It then struck me that this way I was speaking about my memory was too general to be understood.

I think there’s a similar strain to communicate going on in some of these visual conversations. I had befriended and photographed a family in the Old Town of Kashgar before the neighborhood was restructured. The father of the family refused to draw anything on this picture because his religious beliefs forbid using figurative imagery, but he let his son and wife draw – a western style house and what looks like a beautiful woman. Some of the images beg the question ‘Who are the drawings are for, and who are they about?’

Documentary, or reportage photography, isn’t part of the visual language in this area, so I started trying to bring in some of the more local visual practices, and asked people to use embroidery and wood carving tools on the pictures. The project started reflecting the ways our visual tools intersect, becoming more about us together.

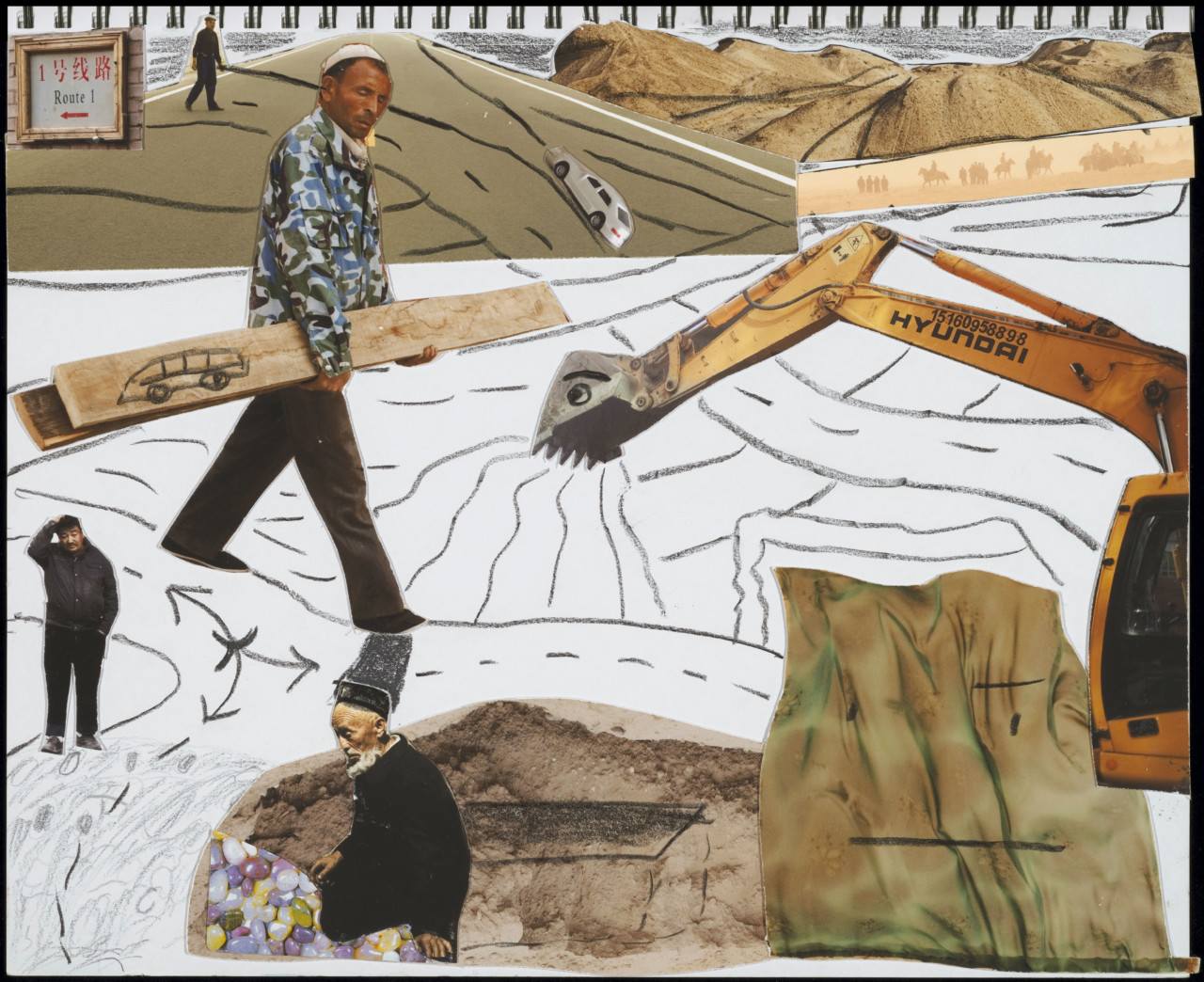

I also invited people to make collages out of my pictures, thinking that this process of tearing apart and rebuilding would mimic the changes happening in the landscapes of Xinjiang, but that they would be put together by people who were affected by all the change. I left the picture cutouts overnight and one artist proceeded to not only use up all of the prints I had brought, but draw over other people’s artwork. At first I was appalled, but as I thought more about it, I saw that this act further blurred the idea of the singular artist – the images weren’t just blurring the line between me and a Uyghur individual, but several people were now sharing in the art-making and altering each other’s work, sometimes without permission.

" I think the appeal of this image in the press is connected to our (false) assumption that understanding comes through classification"

- Carolyn Drake

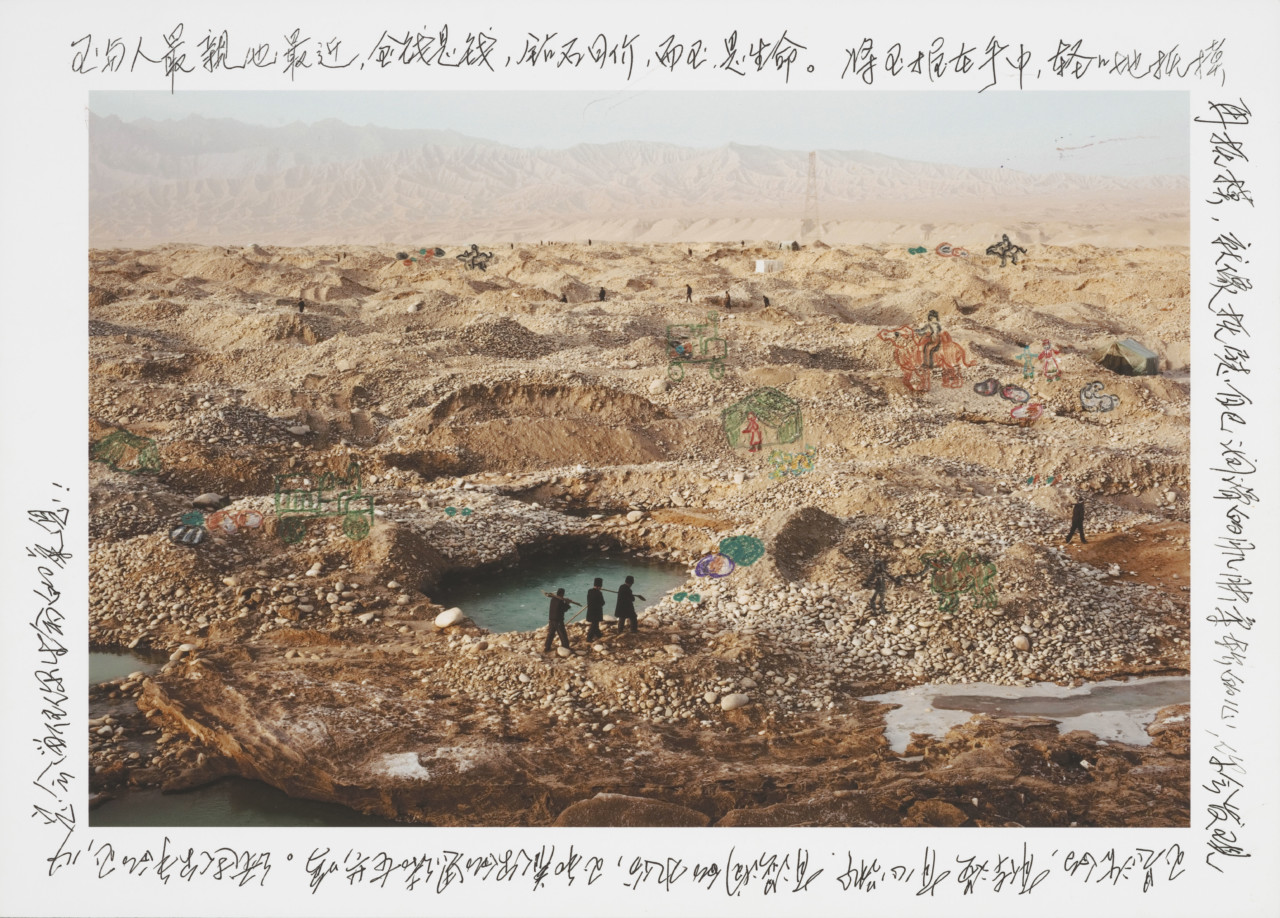

I asked a Han Chinese jade carver to work on a photograph of Uyghur jade diggers on the White Jade River. She inscribed a slogan about the living soul of jade on the border of the picture. This is the image that’s nearly always used to represent this Wild Pigeon project in the press. I’m conflicted about this – it’s the only image made by a person who identifies as Han Chinese, yet the project purportedly aims to elevate Uyghur perspectives. I think the appeal of this image in the press is connected to our (false) assumption that understanding comes through classification. We see the letters as ‘Chinese’ and immediately understand this is about China. It’s easier and more comfortable to see things that speak to what we already know, in a way thats familiar. But what do we really get out of that?

The title for this body of work and book – Wild Pigeon – is borrowed from a fable of the same name by author Nurmuhemmet Yasin. It’s tale of a bird who sets out on a journey of discovery, but is captured and caged by humans. In the end, the pigeon commits suicide rather than live a life in captivity. Chinese authorities interpreted the story as a criticism of state control in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and sentenced the author to 10 years in prison. He has since disappeared.

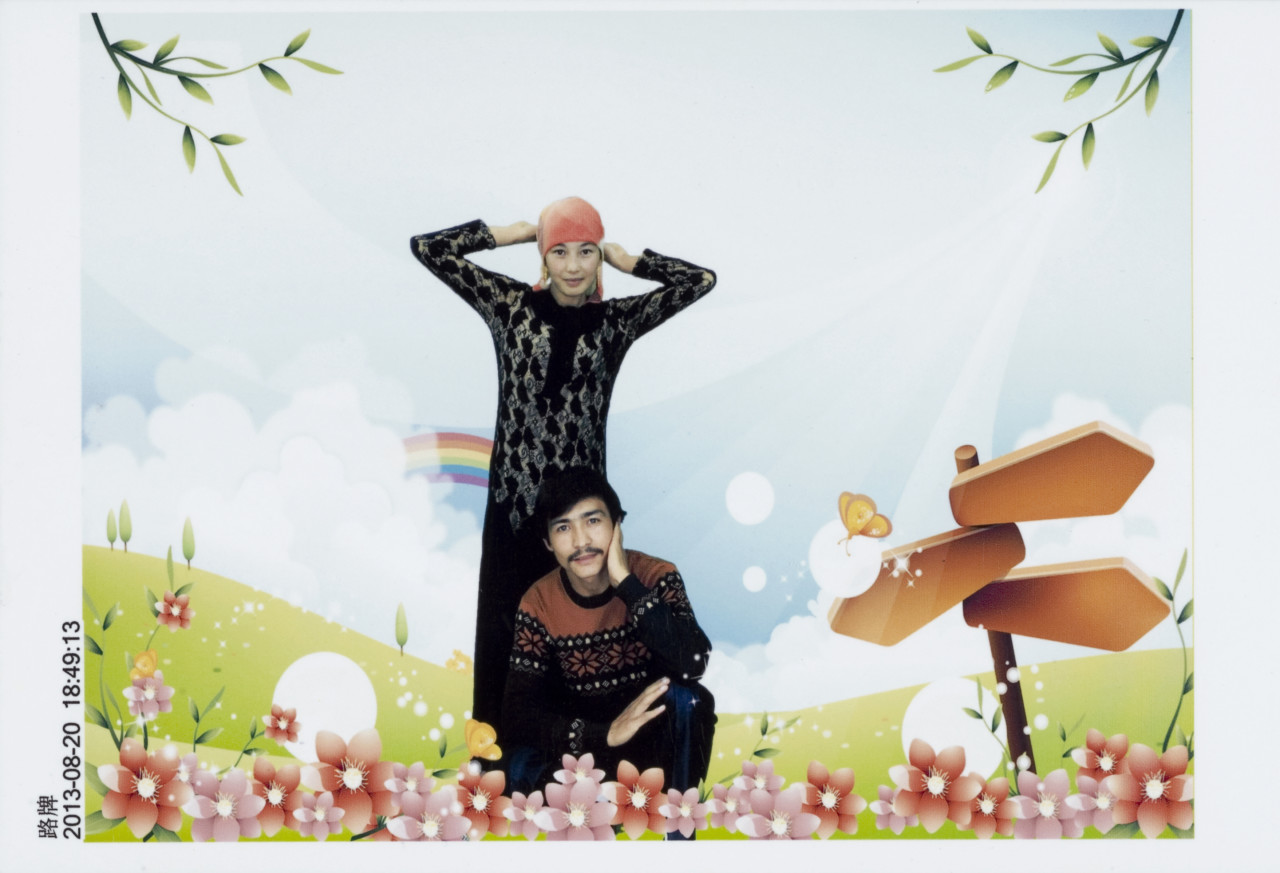

Paradoxically, despite the hero of the story dying, Wild Pigeon ends happily. I wanted to bring that positivity and note of hopefulness into the ending of the my photo book, so I included a booklet of images collected from customers at a mobile studio. Most Uyghurs aren’t permitted to leave China so I thought these self depictions of Uyghurs in foreign landscapes were a powerful demonstration of the imaginative potential of the photograph and represented a small a way for people to reclaim their agency.