A Sense of Community: Wolverhampton in the 1970s

A decade after Enoch Powell’s infamous speech on immigration, Chris Steele-Perkins traveled to Wolverhampton to photograph the communities most affected

The Black Country, west of Birmingham in the West Midlands, United Kingdom earned its namesake, so they say, because of the smoke-filled skies produced by the abandoned factories of the industrial revolution of the mid-19th century. Just on this region’s borders sits Wolverhampton, a city whose skyline is punctuated by the chimneys of the Bilston Steelworks and Goodyear Tyre factory.

In 1956, Wolverhampton’s industry was booming and it was popular opinion that to fuel further growth the workforce needed to be expanded. The Wolverhampton Express and Star published stories stating: “If Britain’s present boom is to be maintained,” recruits “must come it would seem, from abroad, from the colonies, Eire, and the Continent”. Keen for economic growth, the government had long since been encouraging commonwealth immigration in a bid to support the post-war reconstruction but soon found it was unprepared for the inflow of people who arrived seeking employment in the factories. As a result, relations between the native residents and immigrant newcomers could, at times, be fraught.

It was within the context of this tension that Enoch Powell, the Conservative MP for Wolverhampton, gave one of the most controversial and divisive anti-immigration speeches in British political history. On April 20, 1968, Powell stood in the Birmingham Conservative conference and gave an address in which he compared “opening the floodgates” to immigrants to “watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre”. “I, like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood,'” he said, quoting from Virgil’s Latin poem The Aeneid.

"[The series] happened ten years after Powell, but this stuff doesn’t wash out that quickly"

- Chris Steele-Perkins

Upon giving the speech, which became known as the ‘River of Blood’ speech, the politician was immediately expelled from the Shadow Cabinet for the inflammatory comments, but its meteoric impact had highlighted a divide within the nation with stark relief, and its legacy has continued to cast a shadow on Wolverhampton’s race-relations since.

Chris Steele-Perkins was studying at Newcastle University when he read about Powell’s speech. “It wasn’t a surprise. Powell was on the right of the Tory party, and he had been banging on about immigration before,” he recalls. “It was just that this was the most extreme version of this kind of prejudice that he had come out with.” Exactly a decade later, the Magnum photographer would find himself in Wolverhampton. In anticipation of the speech’s anniversary, The Sunday Times Magazine commissioned Perkins to photograph the city’s ethnic minorities and explore how Powell’s words had affected communities in his old constituency.

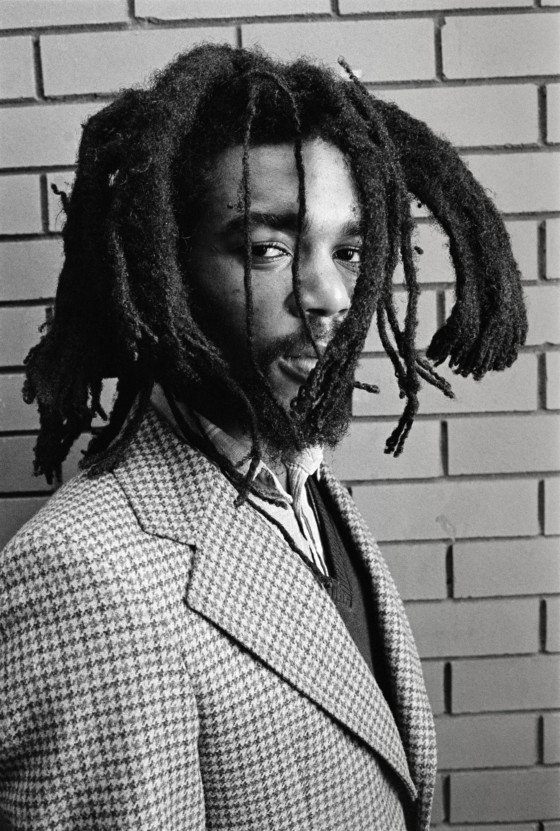

Steele-Perkins hadn’t visited Wolverhampton before but he didn’t expect to find a city remarkably different from the rest of Britain. “I think there was a fairly general anti-immigrant atmosphere of racial prejudice that permeated the whole country,” he says. The immigrant population – largely West-Indian and South-Asian – were being blamed for lowering wages and ostensibly taking jobs. Newcomers experienced “the whole panoply of racism,” Steele-Perkins explains. “They were alienated, picked-upon, given second-hand opportunities” – issues that Powell echoed in his speech as impacting the white-skinned population of Wolverhampton.

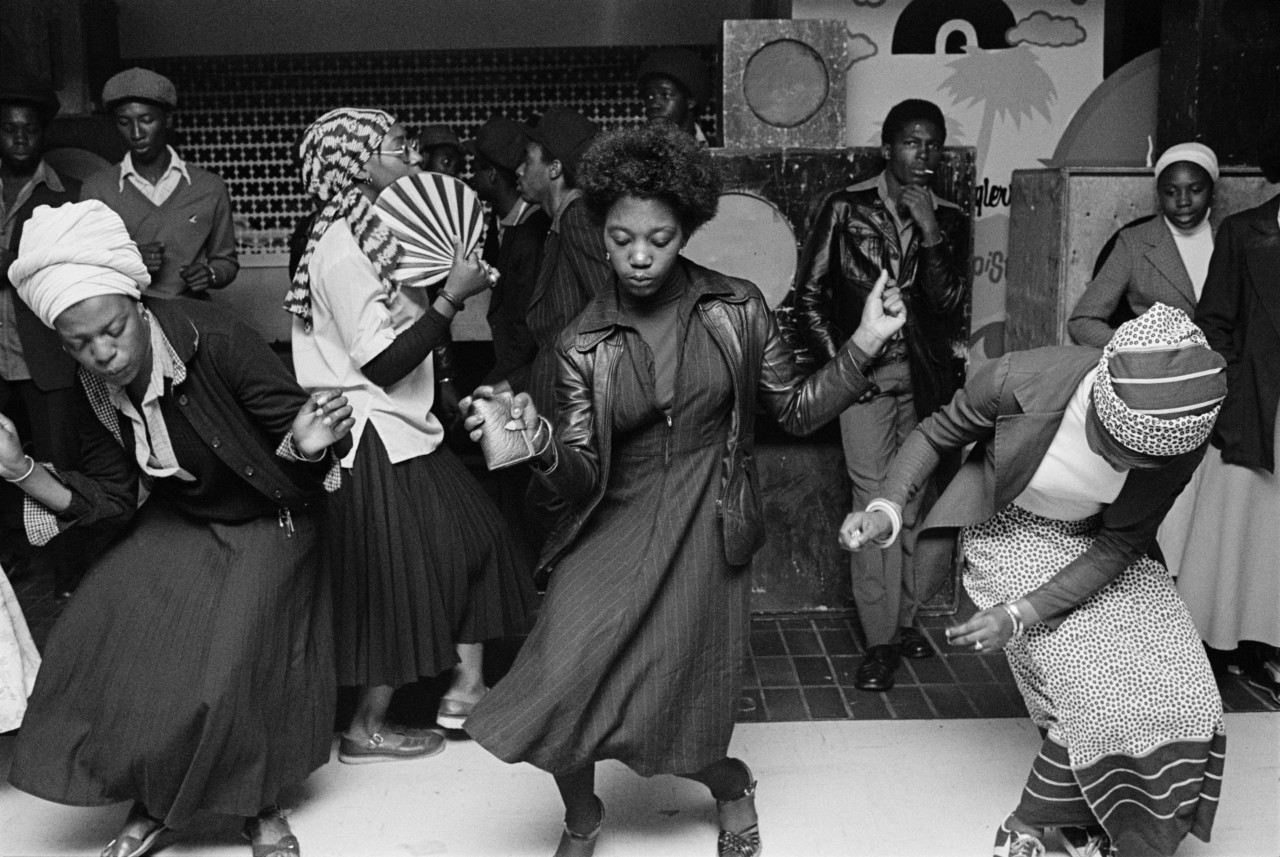

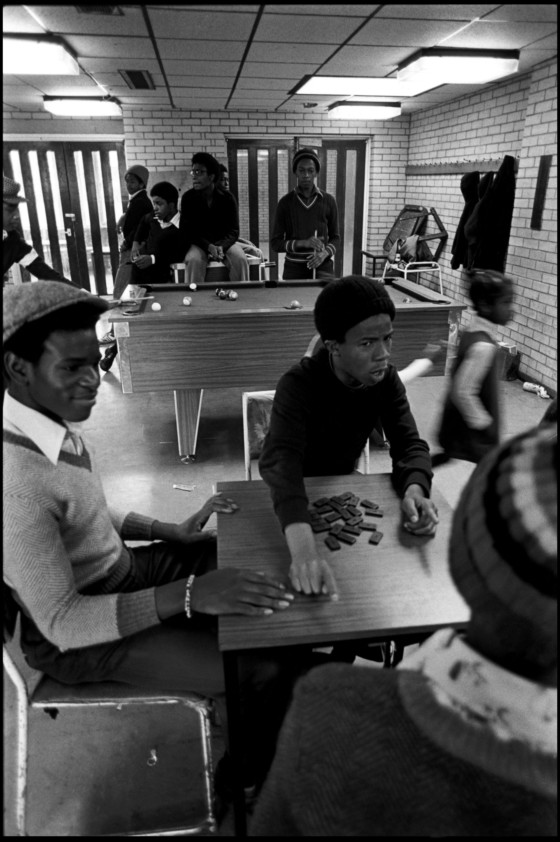

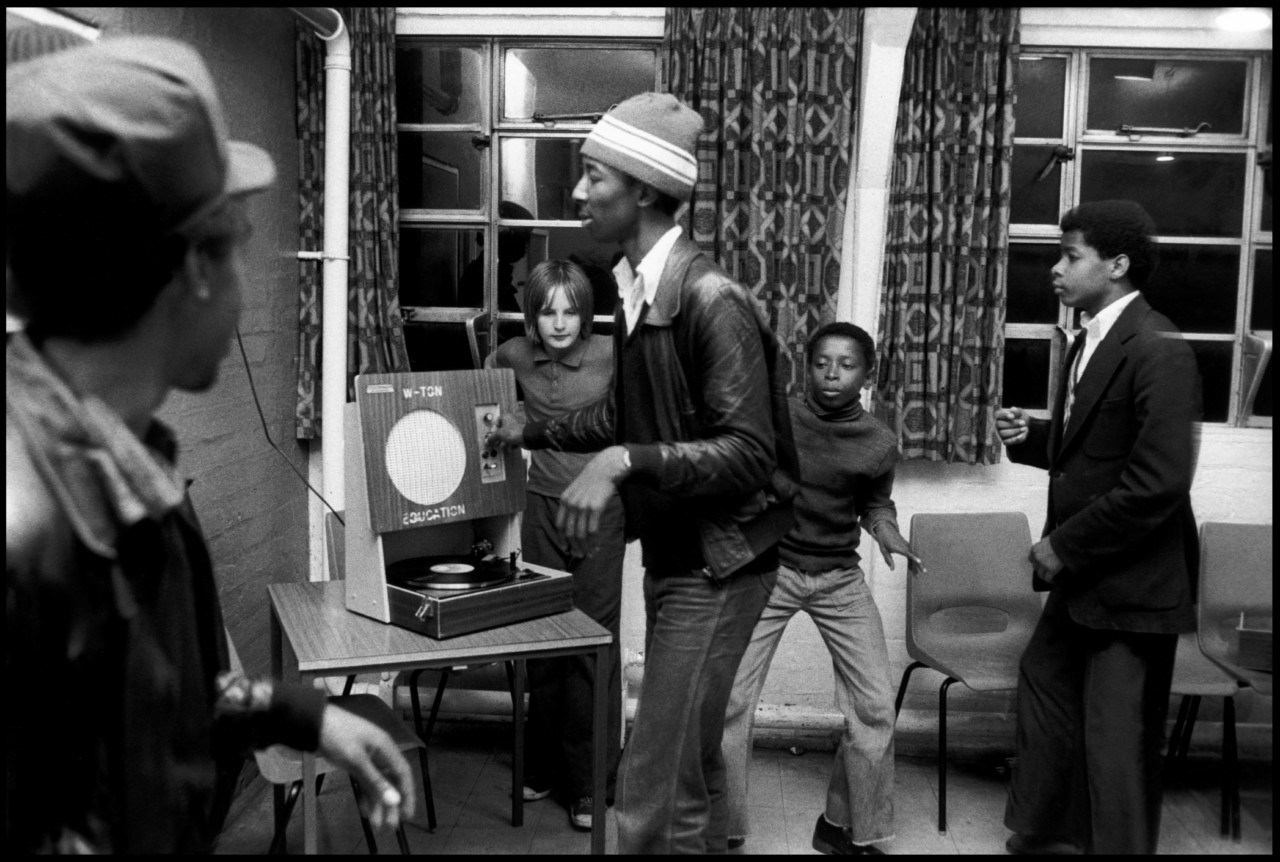

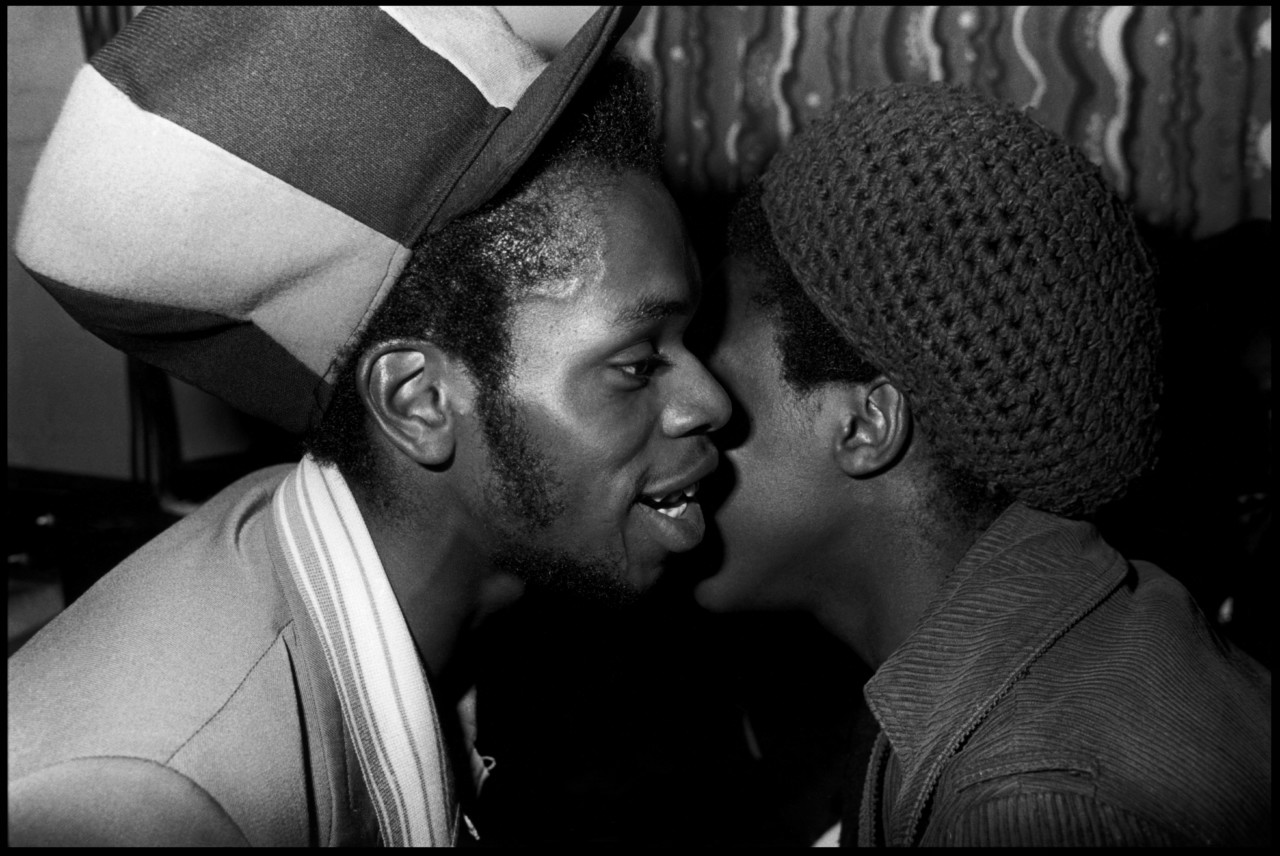

Over the ten days, Chris Steele-Perkins was in-and-out of church clubs, community centers, factories, and playgrounds. His images catch the day-to-day, following individuals as they crowd around the record player, playing dominoes, at prayer or working shifts at the factory. It was a portrait of a community. Although for Steele-Perkins it wasn’t so easy to gauge how the community felt: “I sensed that people would rather not talk about it. It was a nasty stain, but they wanted to move on,” he said, before adding, “This happened ten years after Powell, but this stuff doesn’t wash out that quickly.”

“Journalism didn’t have a great name,” at this time, within ethnic communities in Britain, and so many people were naturally suspicious of Steele-Perkins’s motivations. “We were there to ‘stitch them up’ and call them criminals; it happened to them all the time anyhow. They had read stories about Wolverhampton and problems with crime and so on.”

Steele-Perkins did find some subjects that were open to being photographed: the manager of a boxing ring, or the smiling leader of the streetwise playgroup. Many of his portraits capture the youth, friendships, and familial ties.

"I sensed that people would rather not talk about it"

- Chris Steele-Perkins

Photographing immigrant communities building a life in Britain and the cultural impact of these societal shifts has continued to be of interest to Steele-Perkins. He spent time documenting multi-cultural Brixton and the National Front marches in Lewisham, both in London. “I am interested in England broadly, in the culture that I have been brought up in,” he says. “I think immigration is the biggest possible issue for our culture at the moment.” Steele-Perkins’s latest project, The New Londoners, is an ambitious project that sees the photographer documenting families in London from every single country in the world, in an attempt to show how multiculturalism is an integral part of Britain’s constitution. As Brexit spawned a new wave of reactionary rhetoric, his series put a face to immigration, representing families of inter-cultural Londoners in their homes.

"I can’t pretend it’s something that happens to other people and is not connected with me"

- Chris Steele-Perkins

Steele-Perkins feels a personal affinity with the subjects in his photographs, particularly in relation to immigration in Britain. “I am essentially aware of it, as I am not part of the mainstream group. I have a Burmese mother and an English father, and I wasn’t born in this country,” he explains. “I can’t pretend it’s something that happens to other people and is not connected with me.”