The Perfect Man

How a Charlie Chaplin convention in India led to one of Cristina de Middel’s most complex projects, an exploration of masculinity, culture clashes and gendered perspective

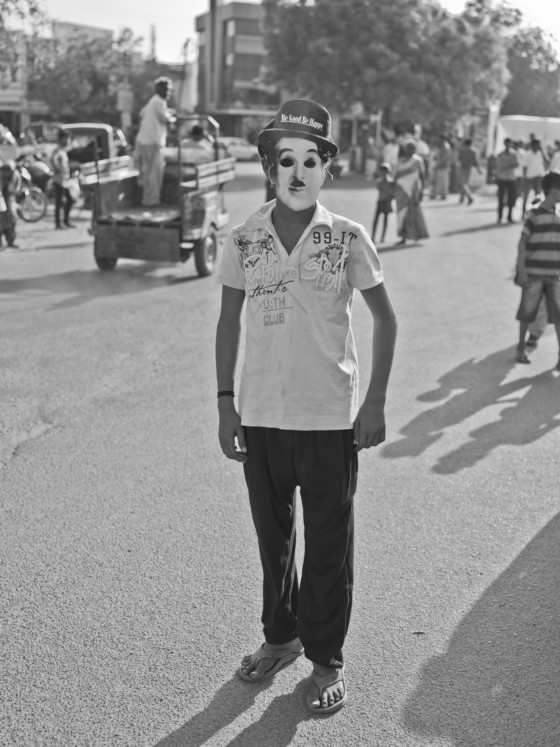

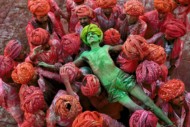

Every April 16 since 1973, in the small town of Adipur in Gujarat, India, ayurvedic practitioner, Charlie Chaplin enthusiast and impersonator Dr. Ashok Aswani has marked the actor’s birthday. What started out as a small homage has turned into the world’s largest Chaplin impersonator convention with around 300 mimics converging on Adipur for the event. When Spanish photographer Cristina de Middel read about this incredible event in an in-flight magazine, she thought it would make a fabulous photographic study.

When Swiss photography festival Images Vevey put a call-out for new work just as Chaplin’s Swiss home, where he lived from 1952 until his death in 1977, opened as a museum in 2016, the photographer seized the opportunity to explore the story that she’d mentally filed away for just such an opportune moment. The project would eventually result in Aswani getting to fulfill his dream of visiting his idol’s home in Switzerland, made possible through the funding and organization of Chaplin’s Museum, Images Vevey and Konbini.

On her initial research trip she learned more of the story of Aswani, who, having first seen a Chaplin film by chance aged 16 became hypnotized by and totally obsessed with the actor. “He started dressing like him, celebrating his birthday etcetera.,” explains de Middel. “Over the years he became a doctor and therefore quite an influential person in his community and so he spread the passion for Chaplin in this small community in India.”

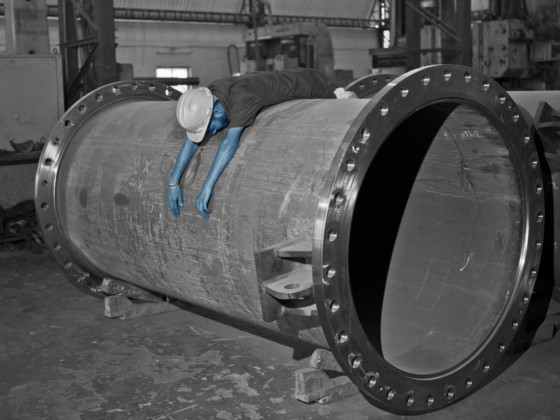

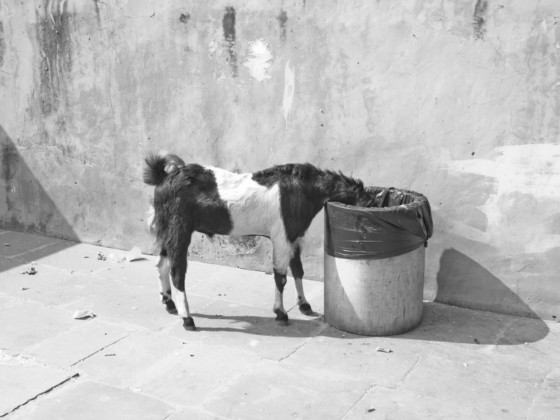

Inspired by Modern Times, a 1936 film written by and starring Chaplin in which his protagonist struggles to survive in the modern, industrialized world – a comment on the desperate conditions faced by many during the Great Depression – de Middel had the idea of exploring the industrial working conditions for men in the Gujarat region through the prism of Chaplin’s legacy. “I tried to mix that anecdote of the convention that happens every year with addressing a more serious subject, which in the beginning was working conditions in India,” she says.

As always in her work, the photographer wasn’t only aiming to explore the issues she was directly photographing, but also the legacy of how these issues have traditionally been photographed within the wider canon of documentary photography and photojournalism. “I try to find the classical approach to classic subjects of photojournalism and reportage,” she explains. Her ongoing project “Gentlemen’s Club” seeks to redress the woman-centered depiction of sex work in visual culture, while her “Midnight at the Crossroads” work redefines clichéd representations of African spirituality.

Chaplin’s legacy is of redefining comedy, argues de Middel. His ability to become either a politician or a laborer, and his comedy genius that saw him sending up serious situations into farcical hysteria was inspirational. “He brought back the clown,” she explains, “but also questions what a clown should be, not just being funny but also sad and ridiculous at the same time. Chaplin’s character is present throughout the project. You don’t really know how to react because sometimes it’s funny when it’s not, sometimes it’s sad when it should be funny.”

Chaplin’s comedy also resonates with her own approach to her work. “I also play a lot with that type of humor Chaplin has in his movies, where you’re actually laughing at things that are sad because he’s using humor to criticize certain aspects of society which he doesn’t approve of, like industrial production and politics and so on,” explains the photographer. Towards the end of this project she utilizes this approach to “address what masculinity is, and what the role of men is, and how this actually affects the role of women in a society like India.”

"I try to find the classical approach to classic subjects of photojournalism and reportage"

- Cristina de Middel

While on her first recce trip in September 2015 de Middel had explored the area, and taken the portraits of men working in factories alongside Dr. Aswani, however, when she returned to attend the convention itself in April 2016 to develop the project further, she was working alone and her experiences differed. As a woman working alone in a region not frequented by many tourists, she found she was unable to walk the streets or to photograph freely. “I was constantly followed by men wherever I went. There was nothing dangerous or scary about it, I just didn’t understand why.”

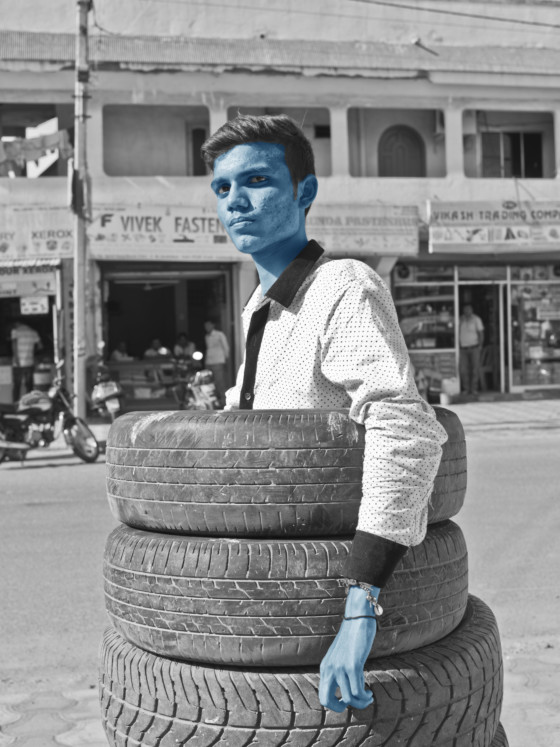

It was at this point, de Middel realized that the only way she could approach this project was by also examining the gendered and cultural perspectives she was approaching the subject from. “I realized that as a woman I couldn’t really talk about it without making a gendered statement, and all that developed into actually asking myself why there is such a cultural contrast in how we understand masculinity and what we expect from men in society,” she explains.

Through this project the photographer sought to explore how the role of men is being questioned. It seeks to examine the expectations society places on them, such as supporting the family or behaving in a ‘masculine’ way, while acknowledging the different interpretations of what that means in different cultures. “It’s really about those expectations from a foreigner’s point of view,” says de Middel, who took care to understand her readings of what she was seeing and experienced came not only from a gendered perspective but one of a Spanish woman, unfamiliar with Indian cultural customs.

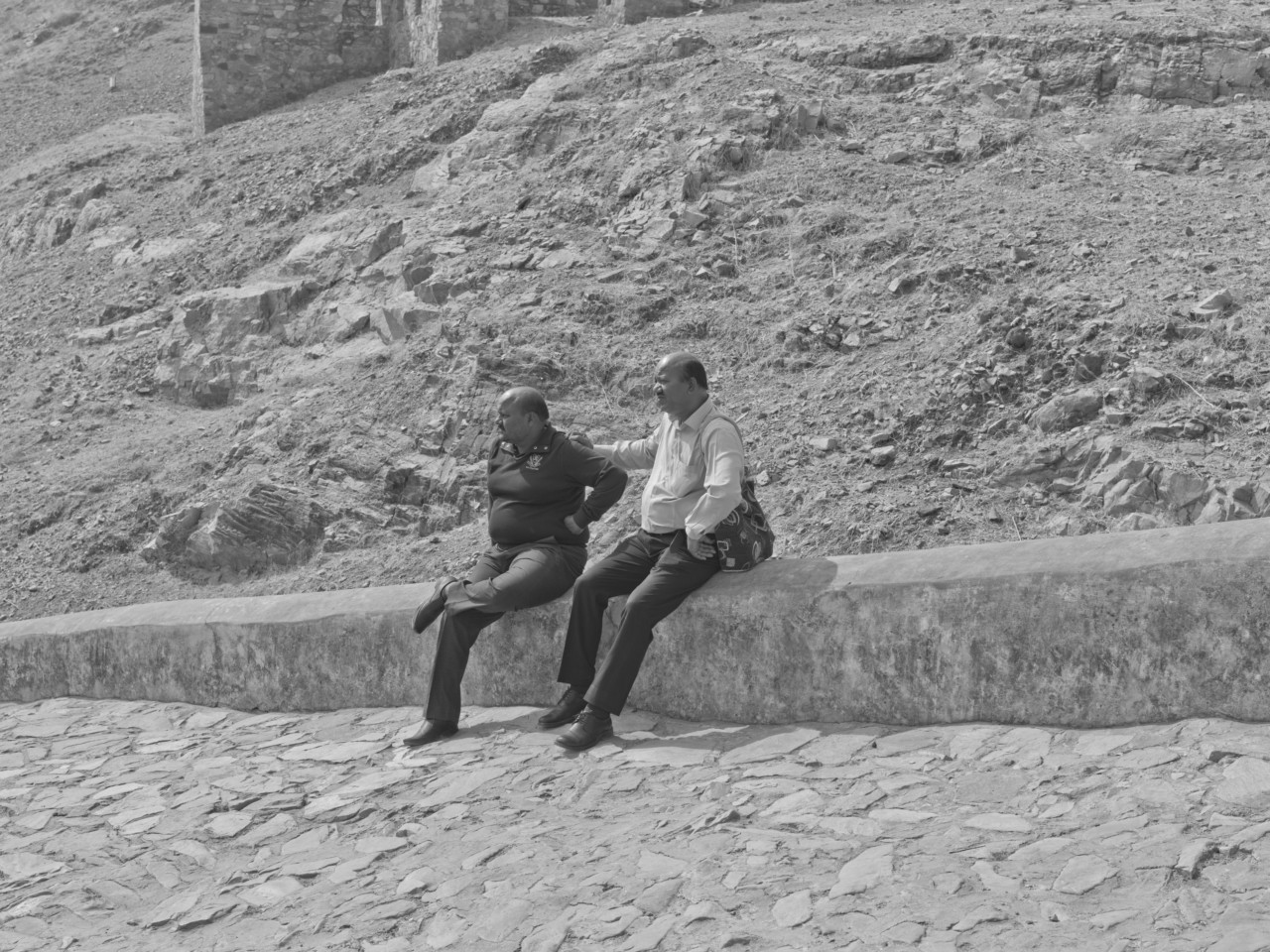

“There are cultural habits that can be jarring to foreign visitors,” explains de Middel. “If you go there, you get used to it, but mixed couples cannot hold hands in public or show any sign of affection, whereas two men can. In India that is totally normal but when you come from abroad it’s very striking that you cannot do public displays of affection, but men can do it platonically and it’s totally normal.”

Chaplin – a purveyor of physical comedy that relied on a universal understanding of body language – is the perfect mode for dissecting this culture clash. “There are a lot of references in this book to body language and hand gestures that we (in Western culture) take for granted but which should be considered differently when you travel abroad,” says de Middel, adding, “It’s quite basic, I’m not discovering dynamite.”

"Every time I am led to produce black and white, I always try to employ a trick that allows me to add one more color"

- Cristina de Middel

The aesthetic of the project – black-and-white photographs with a blue treatment – was another layer employed by de Middel to tie together the complex themes explored in the work. “That was ultra-experimental for me,” she explains. “I’m not very comfortable in my practice with black & white photography, so every time I am led to produce black and white, I always try to employ a trick that allows me to add one more color.”

In this case the blue held a particular significance. “In Hinduism [blue represents] the highest level of spirituality, that’s why some gods are blue, but it is also linked to the color that the manufacturers and the people who work in factories normally wear – the blue-collar workers. The color is a way of linking the two worlds I wanted to unite.”

With so much nuance and careful unpacking of sensitive and complex themes of communication across cultures, through gendered perspectives, and within the context of Chaplin’s legacy, a book was the natural format for the work to be best understood. “I needed text, I needed drawings, I needed references, I needed to have archival imagery, so a book was the best platform for me to combine all these sources of images and information.”

Carefully navigating her position, de Middel’s carefully considered book was, according to her, one of her more difficult projects. “The subject is maybe not as easy to tackle as some of the other books that I’ve made because I’m talking from a specific point of view that positions me on a non-neutral platform – a white woman talking about India,” she says.

The book, detailed and layered as it is, steers away from drawing conclusions; as the photographer says, “I wanted to be extremely careful and present more questions than bring answers.”