Istanbul: A City Transformed

In 2010, Istanbul was a European Capital of Culture, but rising violence in 2015 and 2016 has rocked the city's cosmopolitan foundations

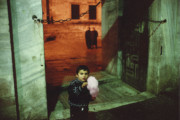

When Istanbul was named a European Capital of Culture, Bruno Barbey captured a strikingly dynamic and modern city at the gates of Europe. He has worked in Istanbul several times over the last decade, and at that time, the city was energized, full of young people hopeful for the future.

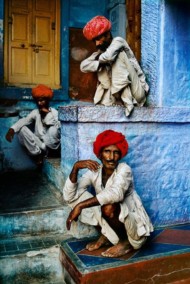

“Cities are made of men and their monuments. These two entities coexist between grandeur and poverty, strength and melancholy. Our job is to show how,” Barbey said in a speech at the Turkish-German Film Festival in March 2017, where acclaimed Turkish photographer, Ara Güler, was presented with an honorary award. “Let’s admit it, we are the hunters of souls. But hunters of a delicate kind, and with a touch of wizardry. We do not want to capture images for our own use but to reproduce them for everyone, to keep them for everyone.”

In recent years, Turkey has become embroiled in the Syrian civil war and resumed its conflict with Kurdish militants. Since early 2015, Istanbul has suffered a series of brutal attacks carried out by ISIS or Kurdish groups, including deadly attacks at soccer stadiums and nightclubs. The migrant crisis, terrorism and a rise in authoritarianism have destabilized the once-exuberant city. Barbey, who has recently been working on a book in China, has suspended his long-term book project on Istanbul because of political repression—though he hopes to complete it in the future.

Journalist Suzy Hansen has written about how life in Istanbul has increasingly come under threat. In 2007, Hansen, who had never even been to Turkey before, won a writing fellowship that sends Americans abroad for two years at a time. Now, she has been living in Istanbul for a decade. Her first book, Notes on a Foreign Country, was published in August by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and was named one of the New York Times’ “100 Notable Books of 2017.” Read an edited excerpt of her book below, which—along with Barbey’s photographs—chart how vibrant, cosmpolitan Istanbul has changed.

The Istanbul airport was modern and efficient, European, and what struck me first was how foreign it did not feel, at least not in the way I expected, which was to be somehow older looking than the decrepit airport in New York I had just left. The metal walls gleamed, porters stood at the ready, there was a Starbucks. Sliding doors beyond the luggage carousels opened like a curtain to a stage where an audience of expectant faces, mostly men with dark facial hair, lunged forward eager to snatch their waddling grandmothers and lead them safely from the crowds. The room felt almost hushed, an obedience to order that I didn’t yet understand. It was the airport of a stable country.

My sleek taxi swept past buildings whose architectural style resembled some strange combination of Florida housing developments and European suburbs, shopping malls as familiar as those I frequented in New Jersey. I never had fantasies about an exotic Orient, but I had not expected globalization to have seeped like heavy liquid into every corner of the earth. The roads were immaculate, tulips lined the drive, and everywhere billboards proclaimed hopeful new construction as if in some 1950s American film reel: the next promised land! As the car merged off the highway, I glimpsed the Sea of Marmara, glinting around those huge shipping tankers. The road then curved around the edge of the old city peninsula, ahead of which I finally saw the miraculous geography of greater Istanbul—three separate pieces of multicolored cityscape emerging from the middle of a bright blue sea. A storybook stone tower stood above a huddle of buildings cascading down a hill to the Bosphorus, which had a delicately webbed bridge spun over it, leading to—Asia? The closeness of the two continents seemed improbable, hopeful, as if the world was not so big and estranged after all; old white ferries scuttled back and forth like beetles dutifully carrying messages between the two lands. Seagulls cawed overhead—to me, the soundtrack of my Atlantic Ocean imposed on an Asian metropolis—and swooped down on tiny rowboats pegged to the shore. I could not believe how beautiful it all was, how it was exactly what I had wished for.

"Istanbul from the grand wide lens of its hilltops made you feel bigger, undiminished and uplifted. "

- Suzy Hansen

Orhan Pamuk made Istanbul’s hüzün famous—a fallen-empire melancholy and loss that suffused the city and its people—but Istanbul, at first, was far too beautiful for me to see evidence of rot. Those first days my leg muscles became sore from walking up and down Istanbul’s steep hills over and over, trying to memorize it all for an impossible mental map. I was in love, as if I had been living in an upside-down world and suddenly someone had turned everything right-side up. Unlike New York, where buildings blocked the sky, Istanbul from the grand wide lens of its hilltops made you feel bigger, undiminished and uplifted. Down the narrow streets, close-up, everything seemed to happen in miniature, like on a movie set, and therefore appeared incomparably more human-size: the peasant woman emerged from her shop sweeping; a man pulled his cart of old broken things; a tiny boy trailed after his father; at night a man peed into the doorway; ladies hobbled slowly, one foot, then the other, side to side; men smoked on stools outside hardware stores; antique furniture piled up outside rickety houses; a peddler sold eggs as if from a concession stand. Head scarves bobbed through the crowds like buoys. Rather than some Islamic menace, they seemed like turn-of-the-century Edith Wharton characters in souped-up bonnets. Covered women looked perfectly normal, here, where they lived, carrying grocery bags, walking to work, far away from the theoretical world in which I had imagined them. The impact of merely seeing foreign things with my own eyes was the equivalent of reading a thousand history books. I found that I was watching life more carefully, that every nerve was alive to my environment.

At that time, American journalists moved to Iraq or Afghanistan, or at least Beirut or Cairo, but Turkey was a country rarely written about in the newspapers, and few people back home, I could tell, thought I had chosen Istanbul for reasons beyond the fact that it was a beautiful tourist destination. My explanation that I wanted to learn about Islam was somewhat true. After seven hundred years as an Islamic empire, Turkey had become a secular republic and, according to the standard history, dispatched Islam from public life. Atatürk had found a way to contain it. For the last eighty years, therefore, the Turks had been wrestling with this secularizing experiment perhaps with lessons for all of us. Wasn’t Turkey the one Muslim country that, in those days, gave hope? Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” seemed more intellectual than martial in Turkey, and I saw the country like some idea lab dreamed up for my benefit.

Turks had long been worried about Islam, and were especially worried the year that I arrived. An election was coming. The reigning prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, was a religious man whose wife wore a head scarf. Now one of the candidates for president in the election, Abdullah Gül, was also a religious man whose wife wore a head scarf. This was new, and, apparently, traumatizing. The president’s office had been created in the image of its founder, the secularist, modernist, raki-drinking, womanizing, trailblazing, ballroom-dancing-soldier-statesman Atatürk—a man who in the 1930s encouraged his adopted daughter, Sabiha Gökçen, to fly planes—and so the idea that that office would now be filled by a man who married his head-scarf-wearing wife when she was fifteen was for many akin to national-spiritual death. Political office, it seemed, was not just about politics but about Turkish identity. Erdoğan and Gül promised to preserve Turkey’s secularist character, and instead used the language of democracy, liberalism, and human rights to argue for their own inclusion in political life. Many of them flat-out hated them. The military, which the secularists viewed as a necessary institution, and which had in the past overthrown the government four times in military coups, was threatening to intervene.

"Cities are made of men and their monuments. These two entities coexist between grandeur and poverty, strength and melancholy. Our job is to show how."

- Bruno Barbey

Despite my confusion, it was an exciting time. On one of my first Saturdays in the country, thousands, maybe millions, of secularists took to the streets in Istanbul and Ankara and Izmir, waving red flags and protesting the presidency of Abdullah Gül. The protest was a bit like Mardi Gras, or the Fourth of July, without alcohol or beads or men sticking their hands down your pants. “Turkey is secular, and will remain secular!” they shouted. On a dreary highway in a northern Istanbul neighborhood, I watched a woman waving her huge flag, which fluttered violently in front of two women passing in head scarves, who had to flinch to avoid it. “We don’t want an imam for president!” other women screamed. (Abdullah Gül was a businessman educated in London, but no matter.) Overwhelmingly, the angriest people were women, who believed an Islamic government might transform their lives. I was reading a book at the time by an academic whose mother went around wearing Atatürk pins and saying, “I have my Atatürk against their veils.” That week, a female think tank writer observed, “If all Turkey’s leaders come from the same Islamist background, they will—despite the progress their have made towards secularism—inevitably get pulled back to their roots.”

Almost ten years later, on the evening of July 15, 2016, I was working at home when a friend from New York messaged to say she saw on Twitter that there was a military coup happening in Turkey. I immediately looked out the window, but for what, I do not know. “It’s either a military coup or a massive antiterrorist operation,” my Turkish friend, Aslı, said on the telephone. Army soldiers had taken over the main bridges in Istanbul, the ones that join Europe and Asia, the closeness of which I had, on my first day in Turkey nine years earlier, seen as hopeful.

The attempted military coup of 2016 was a fracturing of Islamist power, rooted in a long history, and likely one that would emerge ever more important to understand in the years to come. It took me ten years to correct the crude categories I had once imposed on this country; that the so-called Islamists were a group of diverse longings, politics, and histories; and that the so-called secularists were not one monolithic group, either, but Alevis, Armenians, liberals, atheists, devout people, gays, Kurds, leftists, feminists, nationalists, and people who didn’t care about politics or religion at all. The question now was whether in Turkey any such diversity would survive.

After the failed coup, Erdoğan’s purge began. It is difficult to keep count of how many people he has purged from government, military, financial, educational, media, and corporate institutions, but estimates range around one hundred and twenty thousand. Ahmet Altan, whom I interviewed in 2007, was among the hundreds of journalists who went to jail. Members of the democratically elected Kurdish party went to jail, too. One of the last remaining opposition newspapers, Cumhuriyiet, where one of my closest Turkish friends worked, was nearly shut down. Theater directors were detained for staging Bertolt Brecht. Thousands of teachers belonging to the same union were fired. Stories of torture, even rape, began slowly drifting from Turkish jails. Erdoğan began talking about reinstating the death penalty. The period felt like the time after the 1980 coup, when the Turkish military had gotten rid of the entire left and allowed for Islamic conservatism to fill the vacuum. I don’t know what will someday fill this one.

After the coup, I even felt an unexpected sympathy for the Turkish people’s nationalism. I could see how this nationalism—especially at a time when nations from West to East seemed to be crumbling apart—was the force that for some repaired the wounds of a coup in remarkable ways. Even people who hated Erdoğan despised the idea of a coup more. That November, when the sirens went off signaling the anniversary of Atatürk’s death, I watched from my window. A man had stopped in the middle of the street. A woman paused on the curb. Someone got out of his car. Maybe these were people who didn’t subscribe to Erdoğan’s version of nationalism, but no matter; at that stage in world disorder, it was reassuring to see a moment of any nation’s harmony. Even if, toward the end of the siren, a lone, young girl in full black head scarf and dress strode in between the frozen people, walking briskly as if there had been no siren at all.

Excerpted from NOTES ON A FOREIGN COUNTRY: An American Abroad in a Post-American World by Suzy Hansen, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2017 by Suzy Hansen. All rights reserved.