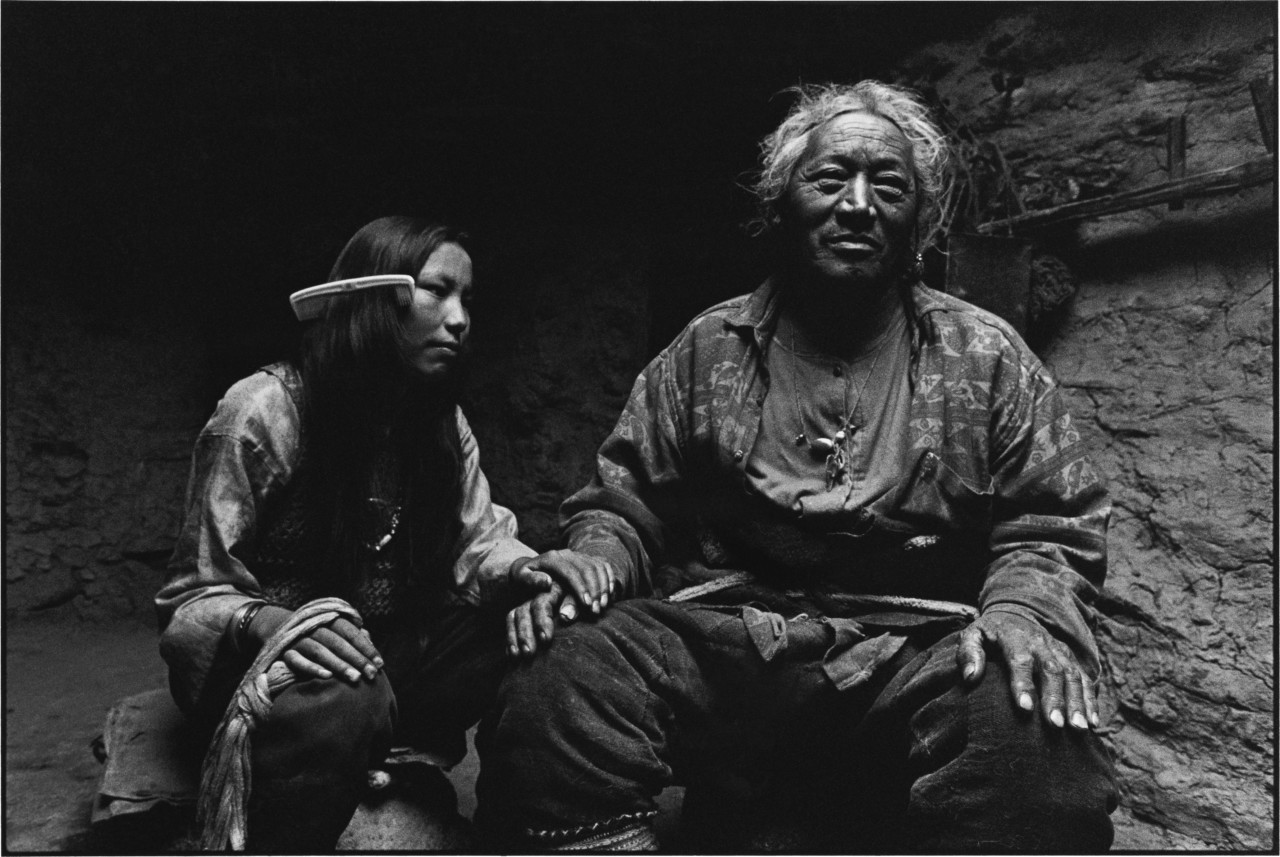

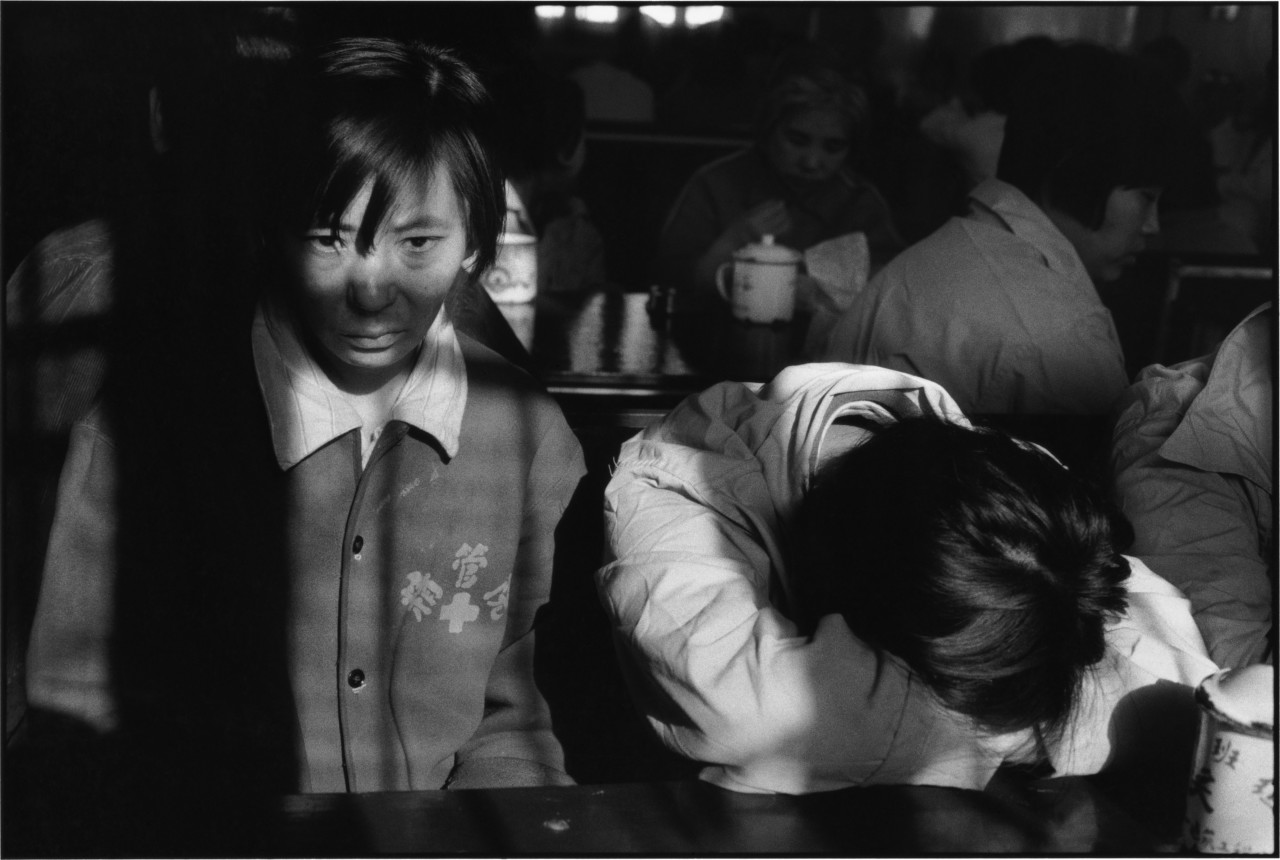

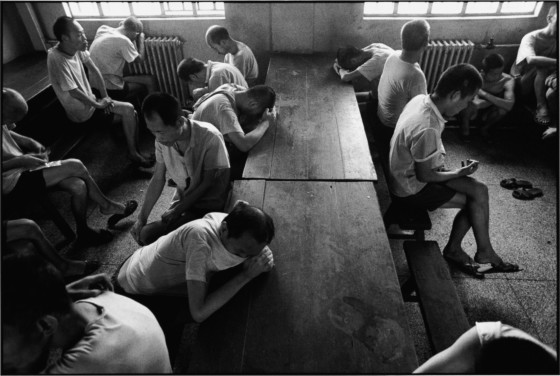

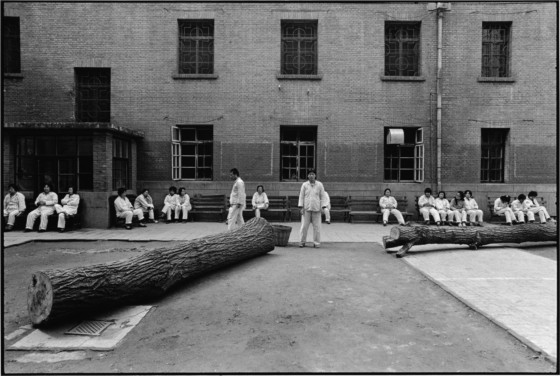

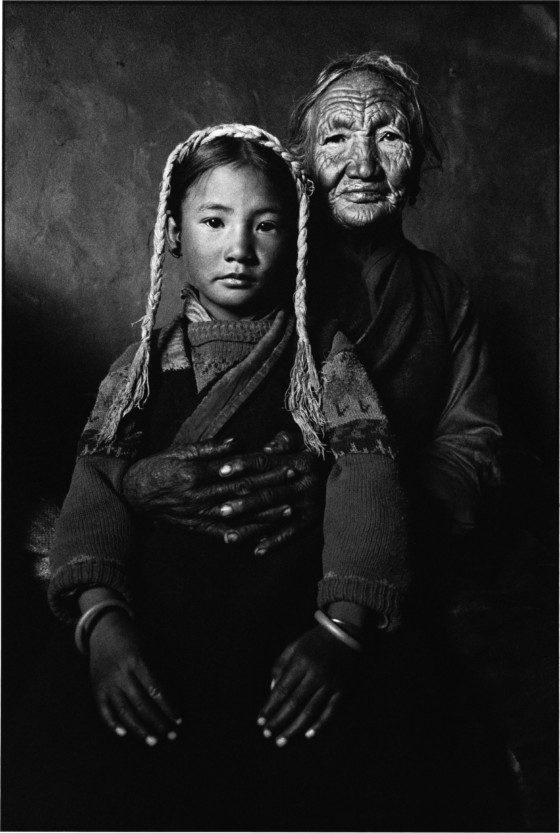

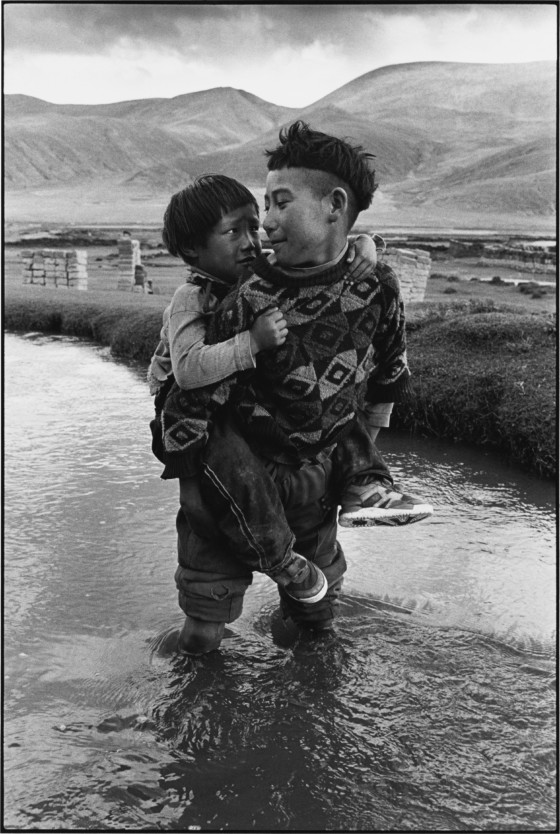

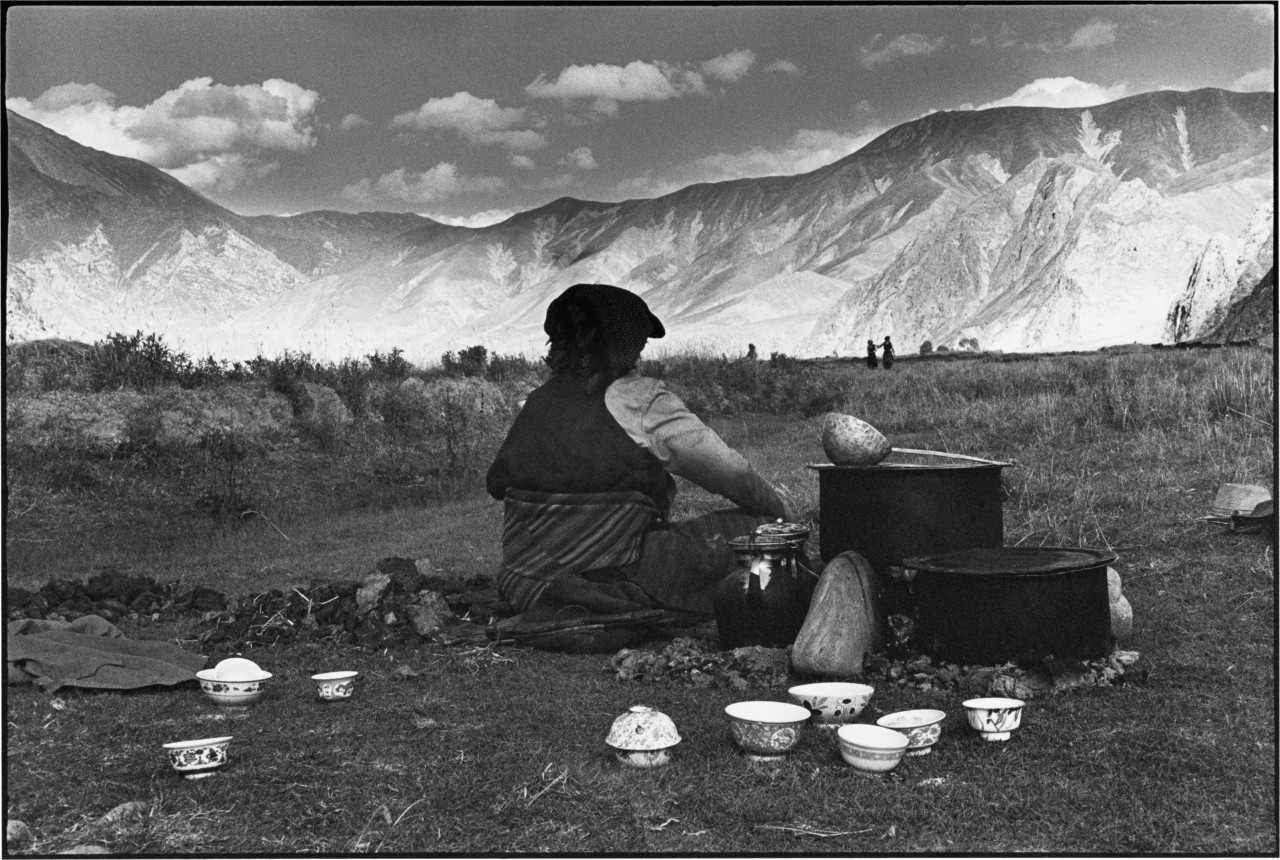

Trilogy draws together three series of Lu Nan’s work created over the course of 15 years; The Forgotten People, a haunting study of the living conditions of China’s psychiatric patients, On the Road, a document of the daily lives of Catholics in China and Four Seasons, a chronicle of the lives of rural peasants in Tibet. Collectively, the projects are part of one major work presenting three stages of inner life – suffering, purification and peace of heart. Here, in an interview originally published in Trilogy, the photographer discusses drawing influences from literature and his fellow photographers, and questioning his own work.

What was your early life like growing up?

I had a neighbour who was a magazine photographer, and he helped me understand the essentials of photography. Later he introduced me to a magazine press, where I served as a darkroom technician for five years. Having read Irving Stone’s Lust for Life (about Van Gogh) and Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence (about Gauguin), I had a hankering for that kind of life. For me, photography was the only medium that could make that wish come true.

Have there been any influential mentors in your career?

During the 1980s, when I first came in contact with photography, China was just opening up to the outside world. We started seeing works by a lot of foreign photographers, and they had an influence on me. One example is Josef Koudelka, whose poetic perspective and clean, strong images affected me. I drew insight from Sebastião Salgado’s mode of work, which was to turn any project he engaged in into a book. I could add more names to this list.

My visual treatments are also influenced by two great painters, namely Piero della Francesca and Johannes Vermeer. Della Francesca’s works have a quiet, solemn atmosphere; they have clear spatial structure and the figuration is unassuming yet powerful. Johannes Vermeer’s pictures portray simple settings that are serene yet full of poetic feeling, displaying the tranquil beauty inherent in life. His works had a big impact on me, as well.

Three people from outside the visual arts also exerted an important influence: Martin Buber, Marcel Proust, and Johann Goethe. Almost every day during my six years of shooting The Forgotten People and On the Road, I leafed through Buber’s book I and Thou. Although I did not peruse it further while shooting Four Seasons, that book had a big effect on my trilogy from start to finish.

I spent over ten years learning from Proust. I read the entire Remembrance of Things Past twice, and I flipped countless times through the final volume, Time Regained. When artists speak to the world, they do so in terms of a whole. Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past is an organic whole—one that conveys insight into human beings while giving readers the sense of an all-around summation. This had a key influence on my trilogy as it was taking shape as a complete work.

I first began reading Goethe’s books seriously in 1995. I was captivated by his precise exposition, broad knowledge, and exact thinking. Now I realise that Goethe was the mentor I relied on while doing my project in Tibet. During the seven years that I was shooting Four Seasons, I dipped into books by Goethe almost every day. My main sources for learning from Goethe were Eichmann’s Table Talk of Goethe and the novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. I made sure to take these books along on my trips to Tibet. I went there a total of nine times, and each time I read them both cover to cover. Goethe’s thought had a big influence on Four Seasons. As I read works by these three authors, I learned their methods of cogitation and their ways of viewing the world, while simultaneously drawing upon them to guide and scrutinise my own work.

For each project in the trilogy, you have focused on a specific group of people. What drew you to these three groups? Did you always see these three projects coming together as a trilogy?

Because I’m working for myself, my choice of projects is a matter of my own interests. In China, there is not only prejudice against the mentally ill and their families; society even directs prejudice against the medical personnel and nurses who work at mental asylums, causing these medical workers to occupy a low stratum of society.

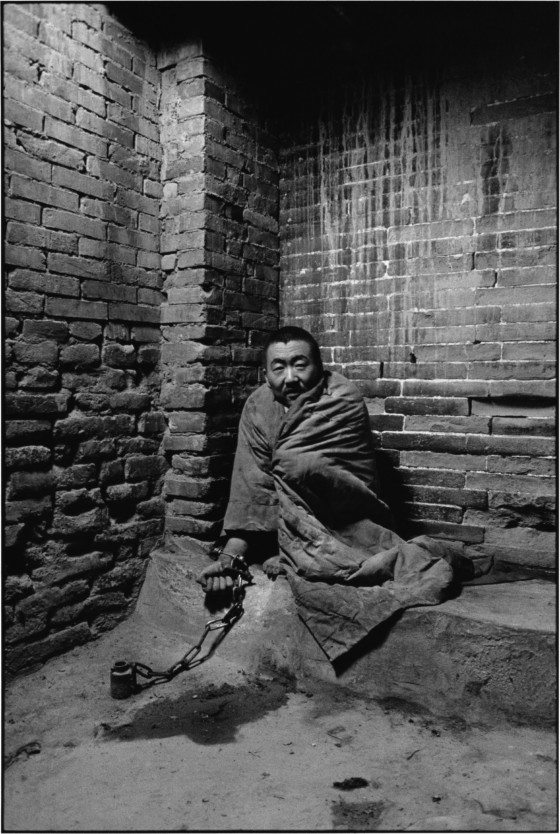

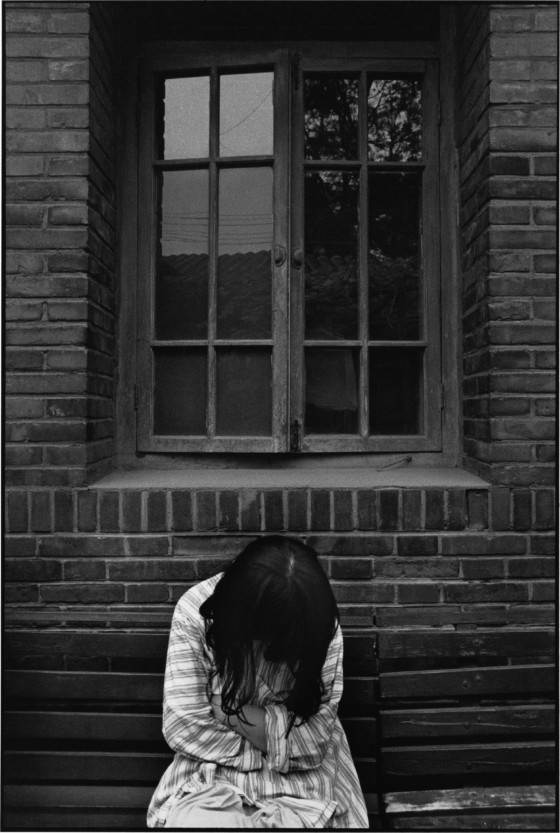

I was curious about the lives of mental patients, so I started with a project on mental hospitals [The Forgotten People]. At the hospitals I found out the tough predicaments that family members of patients faced. In order to present the life circumstances of mental patients in an all-around, in-depth way, I expanded the shooting from hospitals to private homes, and even to the homeless.

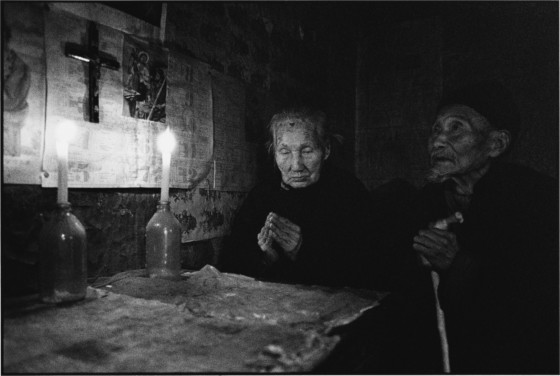

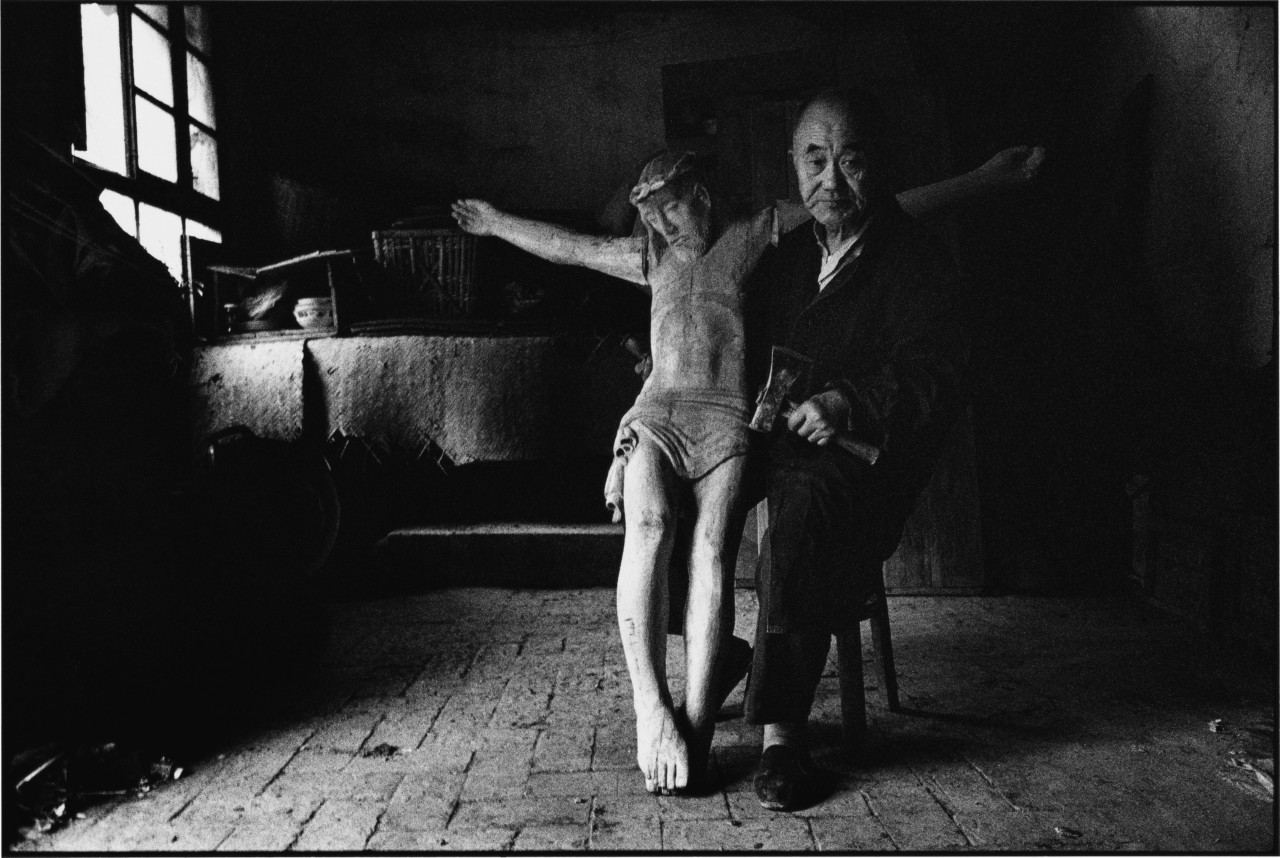

The final photograph in The Forgotten People was taken in a church, showing a priest as he gave a blessing to a mentally ill church member. The moment I took that photo, I knew that my second project would be Catholicism [On the Road], and that my third project would be Tibet [Four Seasons]. If we say that I deliberately chose the project on mental illness, then the following projects on Catholicism and Tibet chose me, because only those three projects would constitute an extended work with inner coherence.

What do you see as the common thread linking the projects together?

The Forgotten People is about suffering and adversity; On the Road is about purification; Four Seasons is about a blessed, serene state—it is about human life as heaven, and humans existing in blessedness. (According to the Buddhist view, heaven is not an abstract idea, it is a concrete reality: when a person’s inner being is in a state of serenity, then that person is living in heaven and existing in blessedness.)

The three component works of the trilogy present three states of the life phenomenon. As life unfolds, we all get a taste of these three life states to a greater or lesser extent. The soul’s paramount wish is to get away from suffering and, through purification, find its way to a blessed state of peace at heart. This wish is what connects the three parts together.

"The soul’s paramount wish is to get away from suffering and, through purification, find its way to a blessed state of peace at heart"

- Lu Nan

Many of the images in The Forgotten People depict harrowing circumstances and deep human suffering. Can you discuss your approach to documenting such sensitive subject matter, as well as what led you to photograph inside these psychiatric wards?

Early in 1989 I went to shoot photos in a mental hospital. As I walked into one of the sickrooms, I saw a male patient standing at a window looking out. I unconsciously raised my camera to look through the viewfinder. As I lowered my camera, I saw that the patient was walking toward me with rapid steps. I thought of running away, but I feared this would hurt his self-esteem. As I hesitated over whether to run or not, he stopped right in front of me. I instinctively protected my camera and lowered my head. My mind was a blank, and I half-expected to feel the impact of his fist. But that blow never came. As I slowly raised my head, I saw his extended hand poised between us. It turned out that he wanted to shake hands.

Beginning from that moment, the label of ‘mental illness’ faded from my mind. In my view, those were human beings first of all, and only then were they mental patients. In The Forgotten People, they were all treated with dignity. Friends helped me to sign up for a press pass, so I could go in and out of hospitals easily.

The work On the Road focuses on church members and their daily lives. What interested you about their lives outside the church?

I am interested in every aspect of love as it is practiced by church members outside the church.

Did you ever encounter conflict from the Chinese government authorities while taking photographs, particularly during your work that would become On the Road?

In China, religion is a sensitive subject. Whether one is shooting photos of an above-board church or an underground congregation, it is possible that one will run into trouble.

In 1993 while shooting photos for On the Road, I was detained for twenty-three days and all my photographic equipment was confiscated, even though I was shooting an above-board congregation at the time. I understand the conditions in Tibet, far above sea level, can be quite difficult and harsh to work in.

Can you talk a bit more about challenges you faced, physically or emotionally, while photographing and creating the work that would become the trilogy?

From 1996 to 2004 I made nine trips to Tibet and stayed three to four months each time. On my last two trips, between August 2002 and May 2004, I worked in Tibet for fifteen months—six months the first time and nine months the second. During the shooting of Four Seasons, I photographed the entire spring planting season twice, and I shot the entire autumn harvest four times.

My mode of working in Tibet was to choose a township each time I went [a township is the lowest-level administrative unit of Chinese government; a township has jurisdiction over several hamlets]. Upon arriving at the chosen township, I would work within the scope of its jurisdiction. During my time there I would not leave for even a single minute until my work was concluded. I did homestays with four different families for four months. Because most farmers’ houses don’t have guest rooms, living with them was a bit inconvenient. Later, I would stay at the township government: sometimes I’d share space with a township cadre or I would stay in an unoccupied government building.

During my time working in Tibet, I had no problems adapting to that setting, because my way of living and working in Tibet was similar to my usual mode of living and working at home. My biggest challenge while working in Tibet was solitude. Because I had four to six hours of reading time every day, I was solitary but not lonely. If there was an inconvenience, it would be the lack of electricity in rural villages, where I had to use candles to finish my reading.

"I hope that by looking into real life, I’ll find something fundamentally and enduringly human."

- Lu Nan

While I was shooting the trilogy, my daily routine consisted of work, reading, and listening to music. I do not watch television. My way of keeping connected to the outside world is listening to the BBC, Voice of America, or the Chinese broadcasts of Radio France. In fifteen years, not a day went by when I didn’t question my own work. That’s why I scrutinise what I was doing by means of reading. This mode of assessing action through thought and assessing thought through action helped me to complete these projects.

The trilogy is concerned with human beings. I hope that by looking into real life, I’ll find something fundamentally and enduringly human.

Can you talk about the concept of ‘fate’ and how it plays into your work?

Goethe said that as long as we’re on the right path, there will be an intangible hand helping us. In fifteen years of shooting for this trilogy, everything I experienced proves the truth of his statement.

Trilogy, published by GOST can be purchased here.

See more work by Magnum photographers in China in the Magnum China book. Read From Civil Strife to Global Superpower: 80 Years of Magnum in China here.