Relics of History’s Dark Chapters

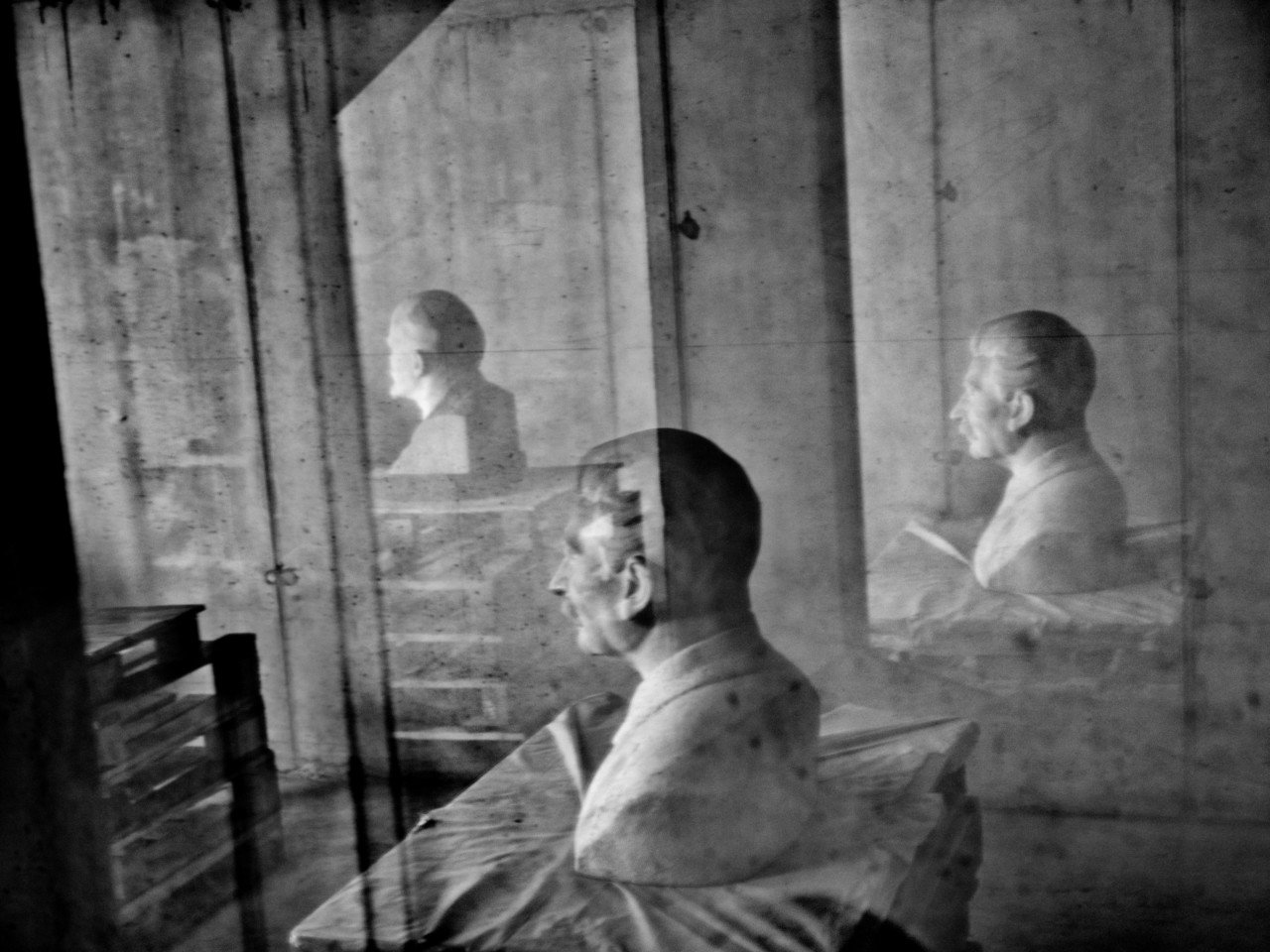

How should society deal with controversial monuments that bear testimony to a difficult past? Matt Black provides a photographic meditation on relics of Communism

The late Czesław Miłosz, Nobel-prize-winning Polish poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat, engaged with ideas surrounding Central and Eastern Europe’s history in living memory. In his 1980 Nobel lecture, Miłosz considered how “a certain equilibrium” could be achieved with the perspective offered by space and time: “A distance achieved, thanks to the mystery of time, must not change events, landscapes, human figures into a tangle of shadows growing paler and paler,” he said. “On the contrary, it can show them in full light, so that every event, every date becomes expressive and persists as an eternal reminder of human depravity and human greatness.”

Today, the United States is grappling with how to contextualize monuments to its Confederate past. In summer 2017, a white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, that was being held in protest of the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, resulted in the death of anti-racism protestor Heather Heyer. In the protestors’ view, the statue was more than a three-dimensional illustration of past events, a relic from history; it was being lauded, celebrated, and becoming emblematic of a newly-emboldened far-right movement. The rally, and Heyer’s death, was not a stand-alone incident but a flare-up in the rumbling national debate over the legacy of the Civil War and its symbols.

"A distance achieved, thanks to the mystery of time, must not change events, landscapes, human figures into a tangle of shadows growing paler and paler"

- Czesław Miłosz

Some are calling for the removal of such monuments. In New York, the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers held its final public hearing on November 28 for citizens to voice their opinions on the removal or reframing of public monuments around the city.

“These monuments are an affront in a city whose elected officials preach tolerance and equity,” reads a letter co-signed by more than 120 prominent scholars and artists. “We encourage the Commission to seize this opportunity to make a brave, even monumental, gesture that will resonate for generations to come, rather than a politically expedient fix that will be easily absorbed — and quickly forgotten — by the status quo.”

"What it made me think of was not so much the past but the future"

- Matt Black

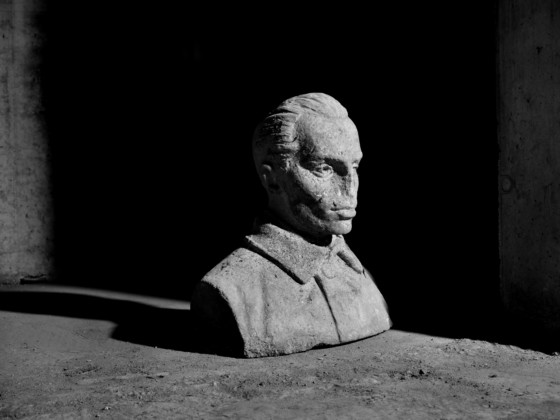

The U.S. is not the first to seek a way to remember and contextualize a difficult past. After the fall of Communism in Hungary in 1989, the capital city of Budapest was also left with relics – monuments, statues, and sculpted plaques – dedicated to heroes of the communist era. It was decided not to keep them in situ, nor to destroy them. Instead, Hungarian architect Ákos Eleőd won a competition by the General Assembly in 1991 with his vision: Memento Park, situated in the rural outskirts of Budapest, an outdoor curated collection of stone walls, sculptures, plaques and statues from former communist Hungary.

The park, as described in associated reading materials, is “not about Communism, but the fall of Communism.” There are no political events or memorials held in the park; as the architect explained, “This park is about dictatorship. And at the same time, because it can be talked about, described, built, this park is about democracy. After all, only democracy is able to give the opportunity to let us think freely about dictatorship.”

Matt Black’s photographic meditation on these memorials in Budapest examines the role of such monuments in contemporary society and considers the role of memory in shaping our world. As Black reflects on the role of these monuments, his thoughts also turn to shaping memory in full light: “What’s the appropriate way to remember troubled chapters of history?”

“What it made me think of was not so much the past but the future. It feels like we are entering another one of these dark chapters, and so it’s hard to look at these monuments without thinking of the backdrop of what’s going on now. The fall of Communism was supposed to usher in a different world, a more open and optimistic world, but it seems we’re going in the exact opposite direction.”