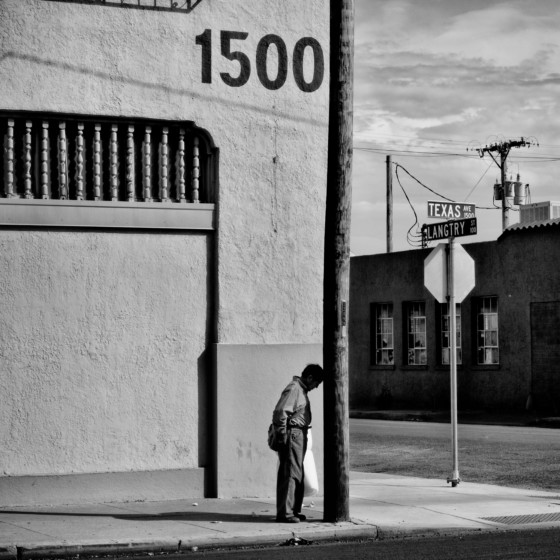

Poverty and Mythologies in America

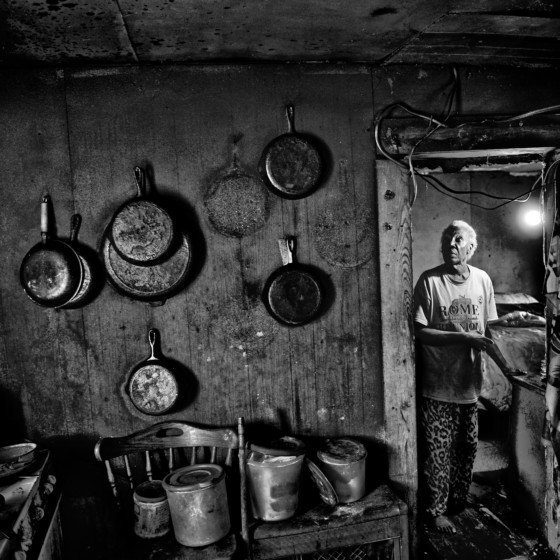

Magnum photographer Matt Black reflects on his ongoing project that challenges the mainstream representation of America's poor

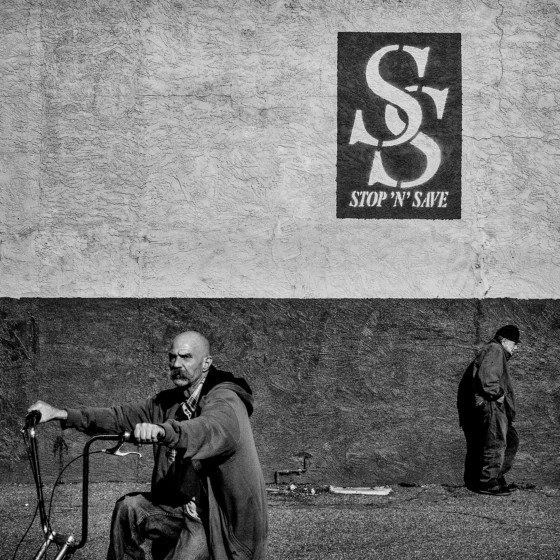

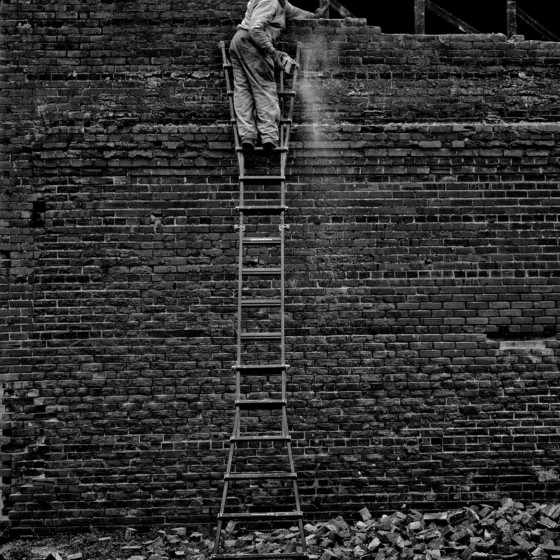

Matt Black’s ongoing project, The Geography of Poverty, looks at designated “poverty areas” — with poverty rates of above 20 per cent as defined by the US census—and examines the conditions of powerlessness, prejudice, and pragmatism among America’s poor. Having travelled 100,000 miles across 46 American states—and Puerto Rico—he has found that, rather than being anomalies, these communities are woven into the fabric of the country, as much a reality as the so-called American Dream.

Indeed, following a two week journey through the United States last December, the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, released a scathing report in which he said: “The American Dream is rapidly becoming the American Illusion as the US now has the lowest rate of social mobility of any of the rich countries.”

As the UN marks the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, Black reflects on the work so far and why dispelling mythologies is central to understanding American identity.

You began the Geography of Poverty project in 2014. What was the genesis?

The work started where I’m from, which is rural California — the Central Valley of California. It is about poverty, but it’s also about America more broadly and which parts of America get attention and which parts don’t. So in the broadest sense it’s about the mythologies and contradictions of America, not poverty in isolation.

And those mythologies generally focus around the concept of the American Dream?

Right.

Your maps show how widespread poverty is in America, but many do their best to ignore it. What do you hope to show that they are not seeing or choose not to see?

I’m trying to challenge these ideas that are way too simplistic about what America actually is. Again, it’s a question of who gets to define what the American experience is. Based on my experience and where I come from, I know it’s a more complicated story.

I grew up in a small town in the Central Valley: four hours south by car is Los Angeles, four hours north is San Francisco, but there was always the sense of being nowhere. It’s hot, dry, agricultural, and poor. It’s California, but not the California that people want to look at or talk about.

How is poverty portrayed in mainstream media and how is that at odds with what you saw?

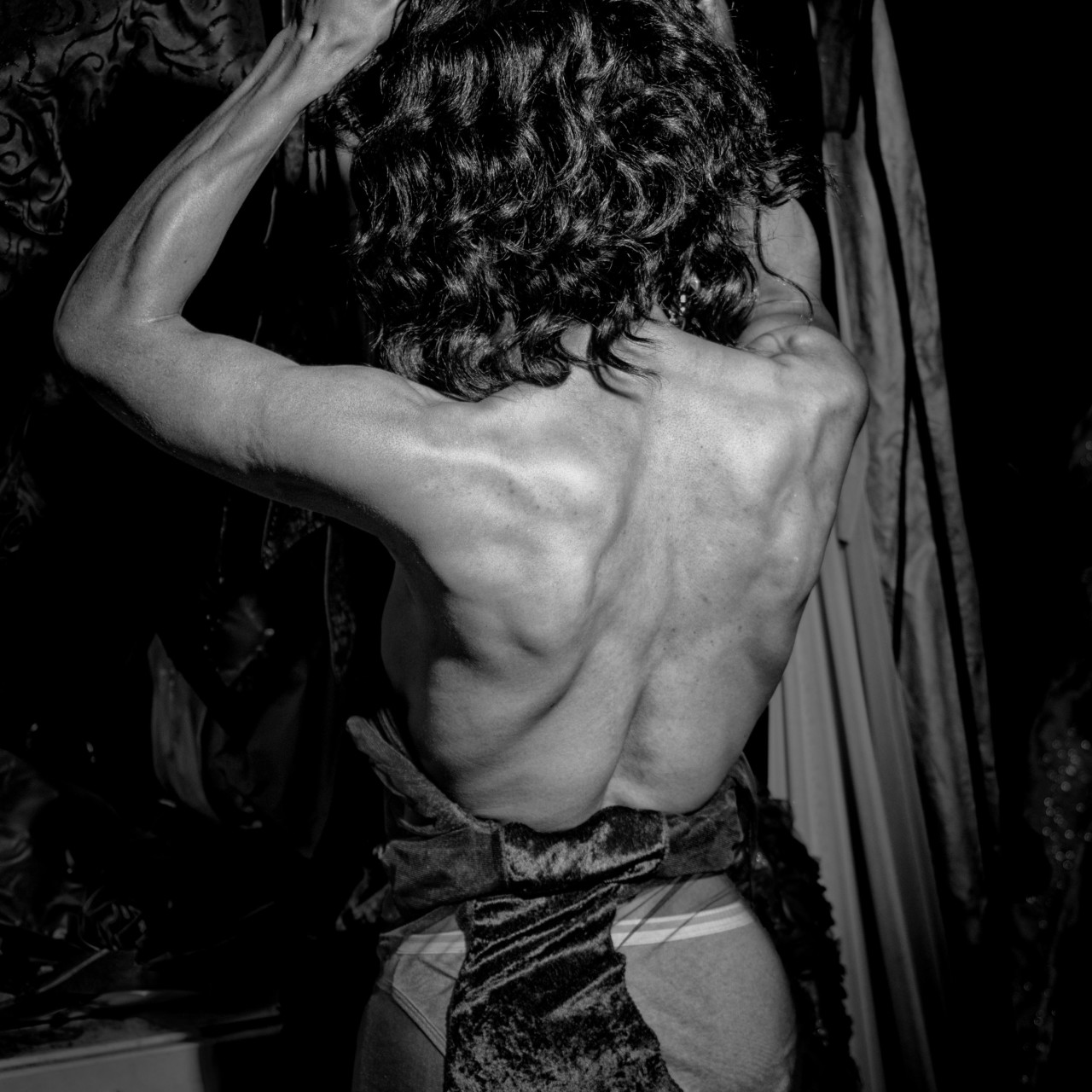

I don’t really know about mainstream media; all I know is the reality that I’m trying to portray. There is an economic factor, but to me that’s more of an indicator, more of an effect than a cause — it’s really about social power. It’s part of a social hierarchy: who gets their needs met and who doesn’t; who’s valued and who isn’t. It’s more complicated than dollars and cents.

Do you think that is in part the fault of how these people’s stories are being portrayed or not being portrayed in the mainstream? Are you frustrated?

Again, I’m not too sure about the mainstream, but, yes, I think there are comfortable ways of telling stories, and other ways that are maybe more complicated and more uncomfortable. Those are the ones that are probably closer to truth.

Do you think that this is because America does have such a strong sense of surface identity, more so than most countries? The idea that has been peddled for generations that you can make it if you work hard enough…Do you think that’s part of why people refuse to believe that being poor is not someone’s fault?

Yes, it’s baked into the American identity—all of those things. And that’s why it’s a particularly complex subject, because of the depth of the stigma and self-worth and everything that’s associated with it.

As part of the UN’s World Poverty Day commemoration it encourages a “genuine partnership with people living in poverty.” Do you think you have achieved this in some way with Geography of Poverty?

It’s important to add that you can’t talk about poverty in isolation without talking about everything else. It’s a part of a social structure, therefore everyone is involved. You can’t objectify into “us” and “them.” That’s part of the point.

"Everything is separating, becoming more unequal - and the whole idea of a common country seems to be coming apart"

- Matt Black

Would you almost reject the label of ‘poverty’? Obviously it is a definitive term—in America someone earning $12,140 or less a year—but does the word itself become problematic because the situation is so much more complex?

First of all, it’s a certain geography that I’m looking at: the poor places in America and what life is like there. These are the places, and the communities within them, that have been at the bottom of this power structure. The question I’m dealing with is what does it mean to be from a place like this, in terms of a person’s lived experience and sense of self? All of these things that are particularly challenging given the mythologies of the American Identity; this is not where you’re supposed to be from.

But yes, the label of poverty by itself is also a problem, because it is a term that isolates. $12,000 is a lot of money in some parts of the world, and that subsidized apartment can be seen as a palace — but not in the US. That’s because poverty is by definition a relative term, and its true import is psychological. That’s the true brutality of it, the true power behind the term.

So it’s almost like these people feel they need to apologise for not living that prescribed American life?

Yes, these myths persist because most people buy in.

You’ve said that poverty is like a ‘culture’. Is that what you mean by that – everything that comes with it, almost forms a culture in and of itself?

Yes, it’s a mindset, it’s an identity, it’s all of those things.

The way your journey has been mapped out serves to give poverty a sort of connectedness, was that your intention – to join the dots, so to speak?

Yes, literally, but I’m also joining places together in a common visual narrative.

At the start of the project, did you have a sense of just how widespread this level of deprivation was and how connected it was?

I was expecting the opposite: that I would really have to look hard and that places would feel very distinct and separate.

It almost dates back to the Native American experience when the first European settlers came, that idea of dividing communities. Is that what you’re alluding to, that ‘divide and conquer’ approach?

Yes, that seems to be the current approach as well.

I’m interested in the platforms you’ve used to share the work—specifically social media and Instagram, which gives you a direct conversation with the viewer. What has the reception been? Have others living in poverty reached out to you to say it’s representing them?

It began as an experiment when I began posting pictures from California, communities that I’ve worked in that are not very well known. I wasn’t at all sure what the reaction would be, but it felt right — a way of liberating the work from a publication or from an impersonal sense of being a production. And it’s been interesting, the most frequent comment—if they can be categorized in a certain way—is, ‘When are you gonna come to my town?’ I think there’s a strong sense of identity in these places. A sense that our reality is not being paid attention to.

At the end point, what would you hope to achieve once this project is finished?

For me, it’s making the statement. But I certainly hope it can inspire a wider view and a more critical look at what American life is.

So offering the tools up for people to investigate themselves, I guess? Using your photography as a starting point for people to understand who they’re living alongside?

Yes, and to put places together and to put communities next to each other that typically you do not see together. That’s a powerful part of it.

One thing in terms of representation more broadly is this: embedded in the work and my motivation to begin it was a sense that reporting on poor places was inherently flawed by a certain way of doing it: you go to a particular place, you spend an immense amount of time getting as close and as intimate as possible, and then you publish that work. Inherent in that process is the idea of poverty again being portrayed as an anomaly and something that is on the fringes, it’s only these particular places, and you have to seek it out. Challenging that idea was built into the motivation of this work; I wanted to critique that way of thinking about poverty — showing it as marginalized as opposed to something ingrained, showing it as objectified as opposed to lived experience.

So it’s about redressing that imbalance, of the way people perceive their country. You touched on this before, that this chasm is widening and according to a UN report, America’s poor are becoming more destitute under Trump’s policies. When you started the project, Obama was in…have you seen any marked change under the new administration?

What I am dealing with is something long-term and something that stretches way back in US history, but yes, all of these forces are intensifying right now and the downward pressure on the poor is getting harder and more intense. Everything is separating, becoming more unequal, and the whole idea of a common country seems to be coming apart.