The Teds

Chris Steele-Perkins on why photographing teen subcultures is so much more than style over substance

The invention of the ‘teenager’ in the 1950s was a global, almost simultaneous phenomenon. Defined by groups of youths rebelling against the expectations of their parents and wider society in their behaviour, attitudes and clothing, movements sprang up in America, Australia, Japan and beyond. Identifiable by their clothes and the music they’d play, these youths revelled in a post-war freedom not enjoyed by the previous generation.

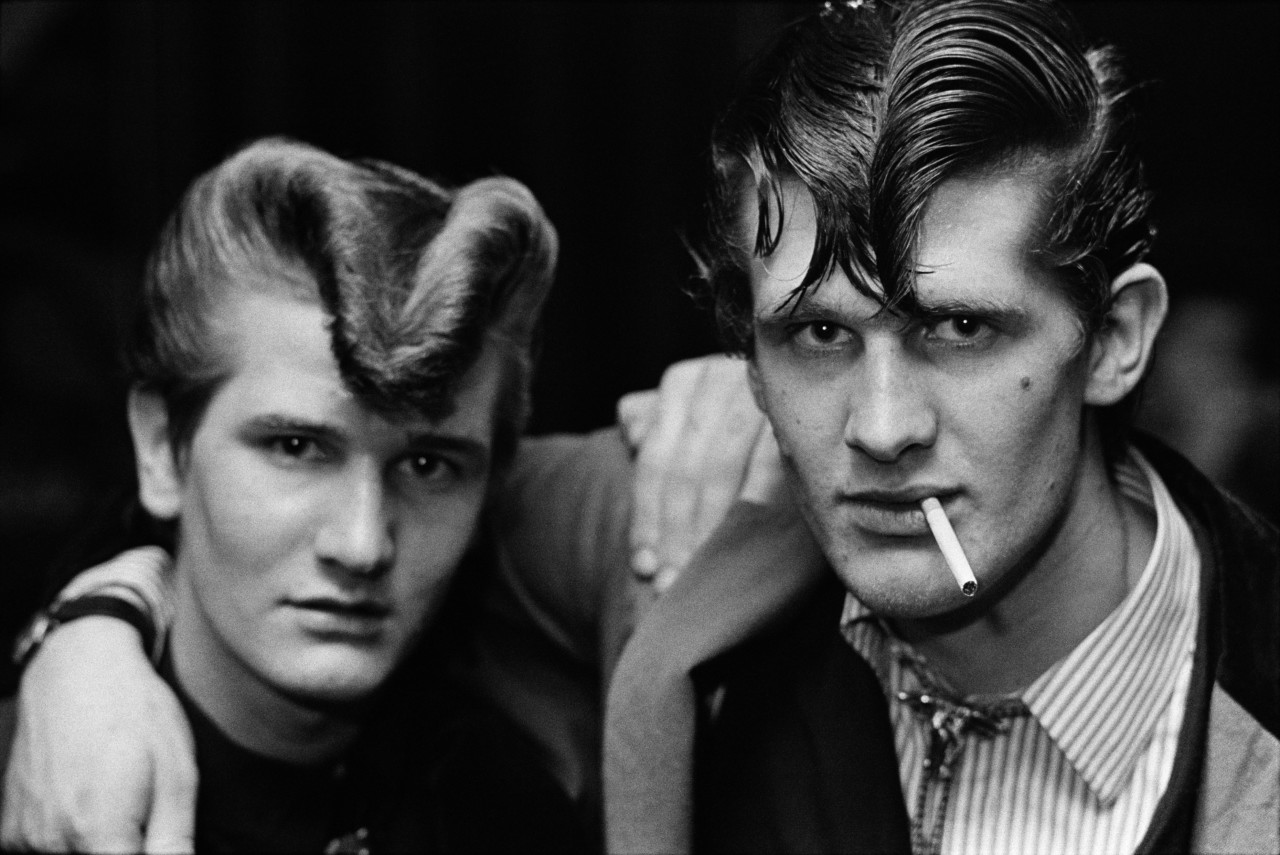

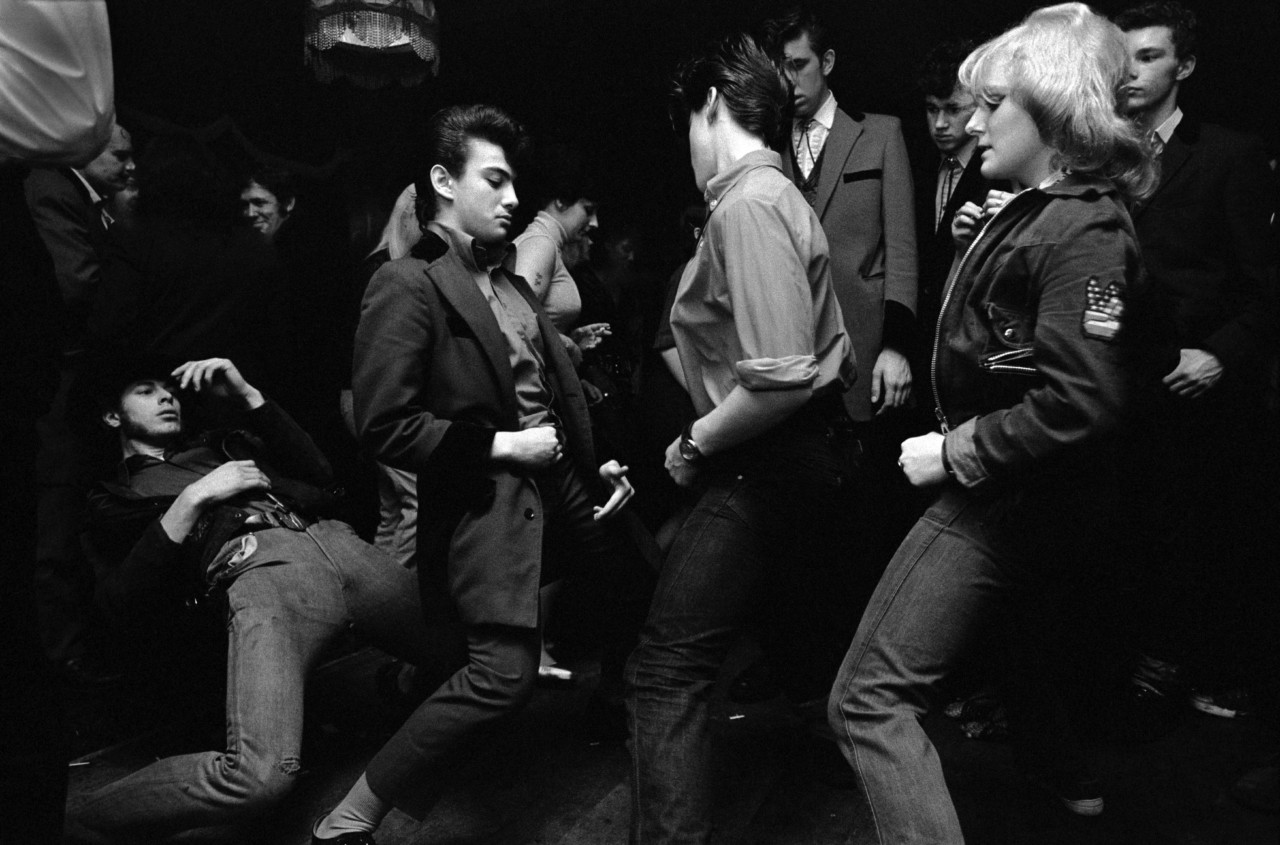

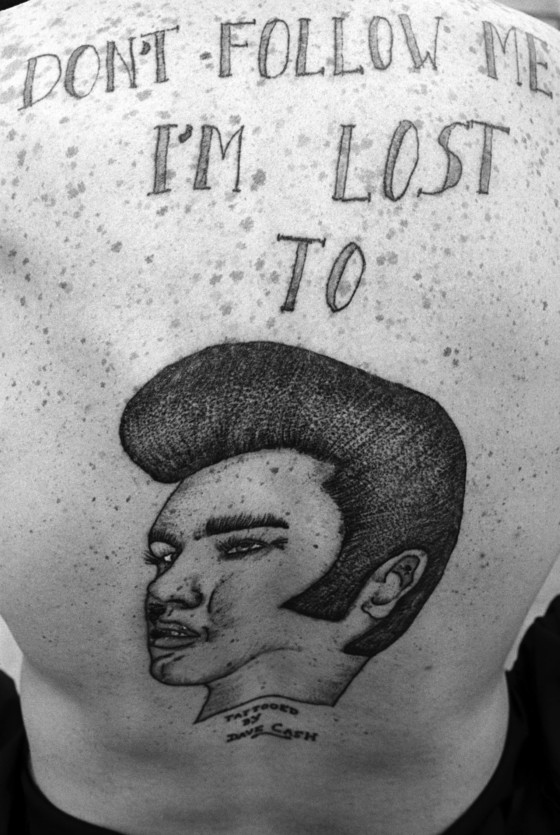

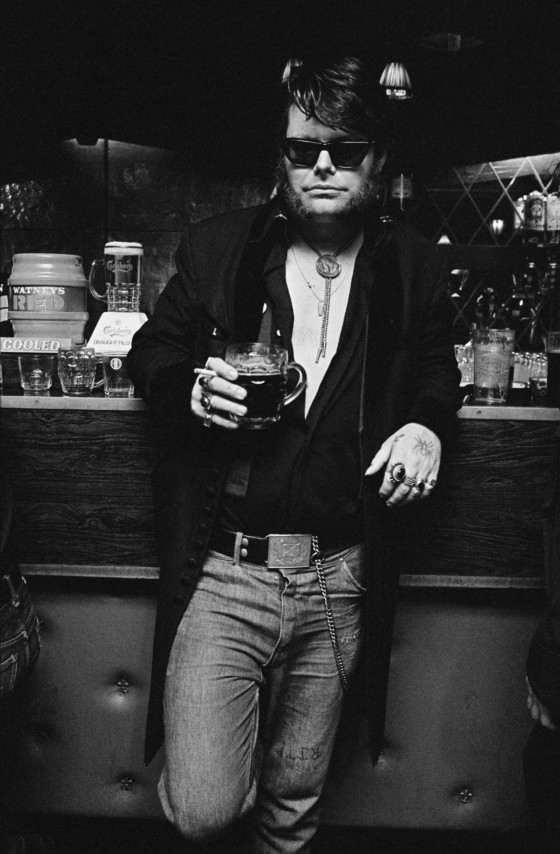

In the United Kingdom, one facet of this newly emerging youth culture was working class youngsters adopting the formal and flamboyant tailoring of Edwardian dress. Known as the ‘Teds’ (nodding to the Edwardian era their look was borrowed from) their jackets – often sumptuous velvets – had wide notched lapels accessorized with a skinny tie or bootlace, and they wore brothel creeper shoes on their feet. “The Ted swaggered with it all out front, male sexuality overt,” wrote journalist Richard Smith. As well as a way of dress and a style of music, owing to several high-profile incidents, the Teds were also associated with wayward and yobbish behaviour and public fights that led them to being banned from some venues.

Trends die, music moves on and teenagers become adults. More youth culture movements would follow, but with them would come a surprising phenomenon of recycling. In a move that on the surface would seem somewhat at odds with the maverick trailblazer idea of youth in revolt, many youth movements have had subsequent second waves. For example, Brit Pop in the 90s borrowed many of its fashion cues from the music and social movement of Northern Soul in the 70s. Some twenty years after the arrival of the Teds, a second wave of young people, who were often not yet born when the original wave hit, began aping the style, music culture and attitudes of their Ted forebears.

Chris Steele-Perkins, along with writer Richard Smith, were commissioned by the now-long defunct New Society magazine to cover the second wave of the Teds for a story, which grew into a self-motivated study of the British youth movement over several years. Steele-Perkins, who at the time was donning a more relaxed style and long hair, remembers the first wave of Teds when he was a child in the 1950s: “Each town had its own Teds who hung around on street corners smoking and sort of grunting at people. My father would rail against them and threaten to turn me over to them if I didn’t behave myself. Maybe that helped to drive my curiosity when I was older.”

To See and be Seen

“The gear: it’s smart; it’s great stuff; it’s much smarter than flared gear. The hair: it’s tidy; it’s not long and straggly. You walk down the street and you get all the old people – the original people who was there in the fifties – looking at you and saying, ‘Ah, look there’s Teddy Boys’.

You get great screws from people. You get people looking at you as if you were really brilliant like, as if you were really great,” said a Ted who spoke to Richard Smith.

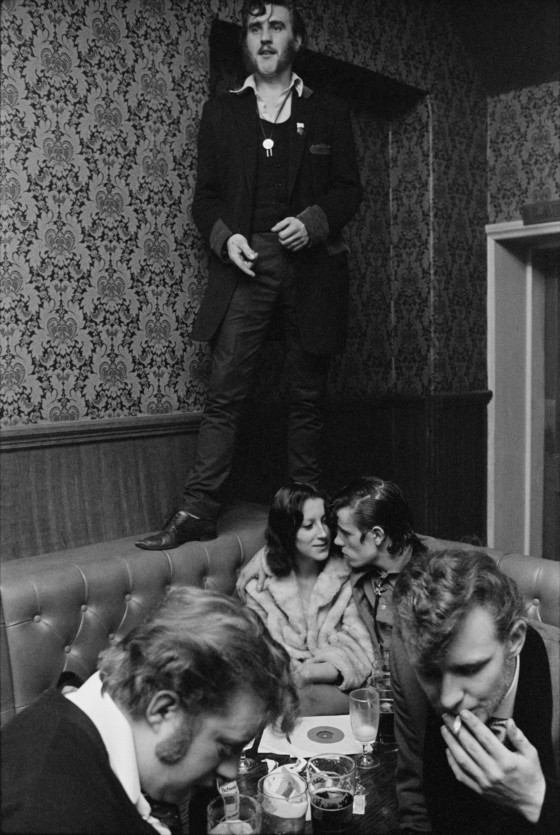

Since the Teds put so much effort into crafting their look, they were expectedly keen to be photographed – “Well, they weren’t there to be ignored; that wasn’t their vision of themselves in life,” says Chris Steele-Perkins. However, this presented its own challenges as the photographer had to work around their propensity to peacock in order to capture genuinely candid shots. “You had to then get to the point where they didn’t just pose for you,” he adds.

"You’re a somebody as opposed to the bricklayer or the butcher’s boy"

- Chris Steele-Perkins

Subculture Vs. Fashion

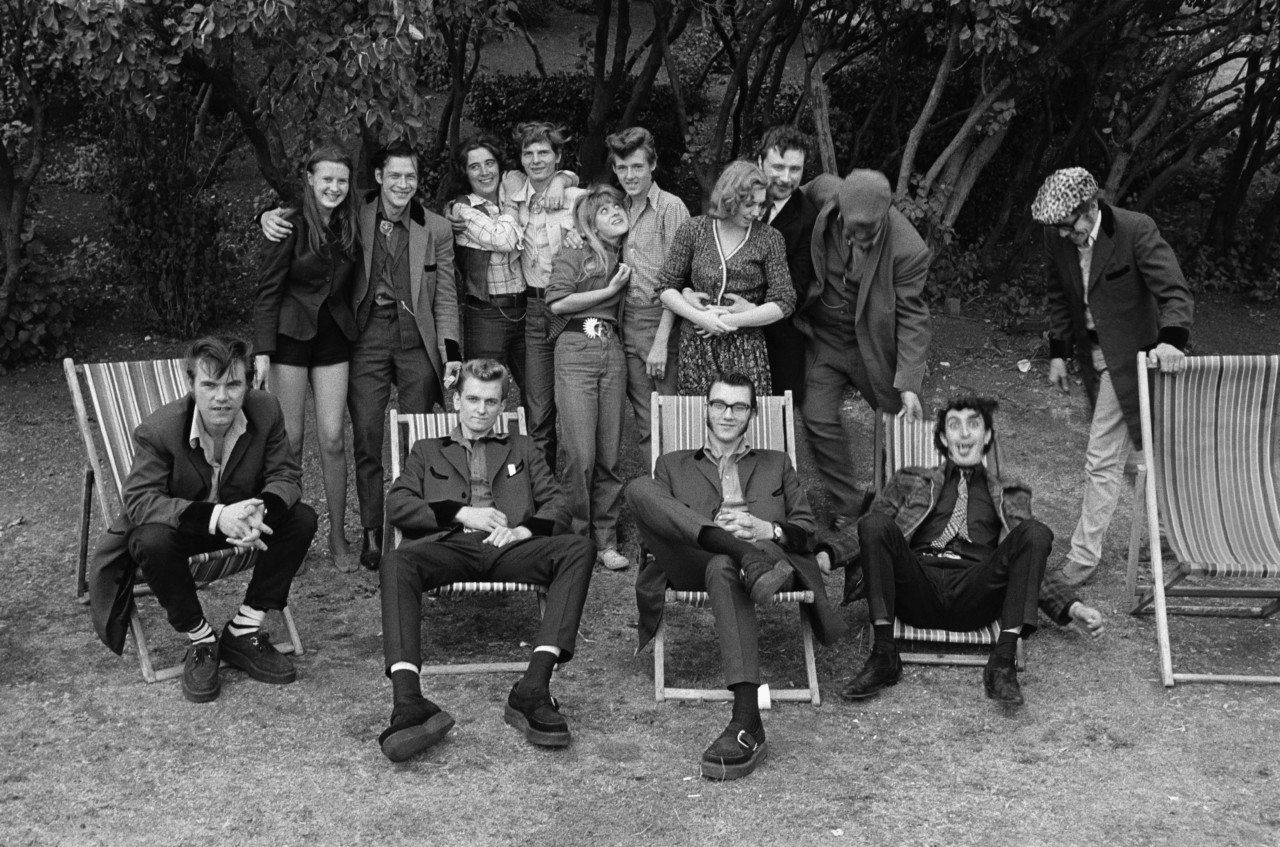

What Steele-Perkins’s photography shows, corroborated by Richard Smith’s writing from the time, is that the Teds second wave was more than just a way of dressing but a lifestyle. We see evidence of the characteristic Teds attitude filtering through to the way youths behave, socialize, interact with and even romance each other in his photographs. Chris Steele-Perkins muses on what separates a subcultural youth movement from a fashion trend:

“It’s the roundedness of it, it has a slang, a code, a dress code, a sort of knowledge of certain areas, esoteric areas that might be rockabilly music, for example. With (1970s UK music and culture movement) Northern Soul, it was obscure songwriters, for example. It could include a dance style, or a way to dress – all those little cultural tick boxes. It becomes part of their identity. You’re a somebody as opposed to the bricklayer or the butcher’s boy; you’re this guy that people think look fancy and they might be frightened of you just because of the clothing you’re wearing.”

The Importance of Documenting Youth Culture

One critique often lobbed at the study of fashion and teen culture is that it is frivolous, but, as Steele-Perkins explains, it, like an anthropological study of the teen species, reveals a significant amount about the society from which it emerges. “What I tried to do was to document a subculture, and quite a major one in British society,” says Steele-Perkins. “I went into their homes and documented them in all kinds of contexts, and the clothes, in the end, become relatively peripheral to the whole thing. I’m not interested in them per se, they’re part of the package. And it’s like most things, leather jackets, you know, it all fades away. It’s much more about identity and who we are.”

This attitude is emblematic of Steele-Perkin’s lifelong photographic approach; it’s what draws him to photograph the subjects he does: families, sports, cultural gatherings, microcosms. “That’s why I photograph England, in particular,” he says. “All my working life I’ve been drawn to these small worlds which have the whole world in them. It could be the Teds, it could be Holkham estate (a private aristocratic estate in North Norfolk); it’s pretty similar in terms of it being a world within a world with its own rules and its own codes.”

A new edition of Chris Steele-Perkins’s book ‘Teds’, featuring written vignettes by Richard Smith is out now, published by Dewi Lewis Publishing. Images from the book, plus several not published before are on display at the Magnum Print Room in London until October 28.