TV Shots: The Olympics

Harry Gruyaert's abstract stills of the 1972 Olympics reveal the universal and timeless appeal of the televised sporting experience

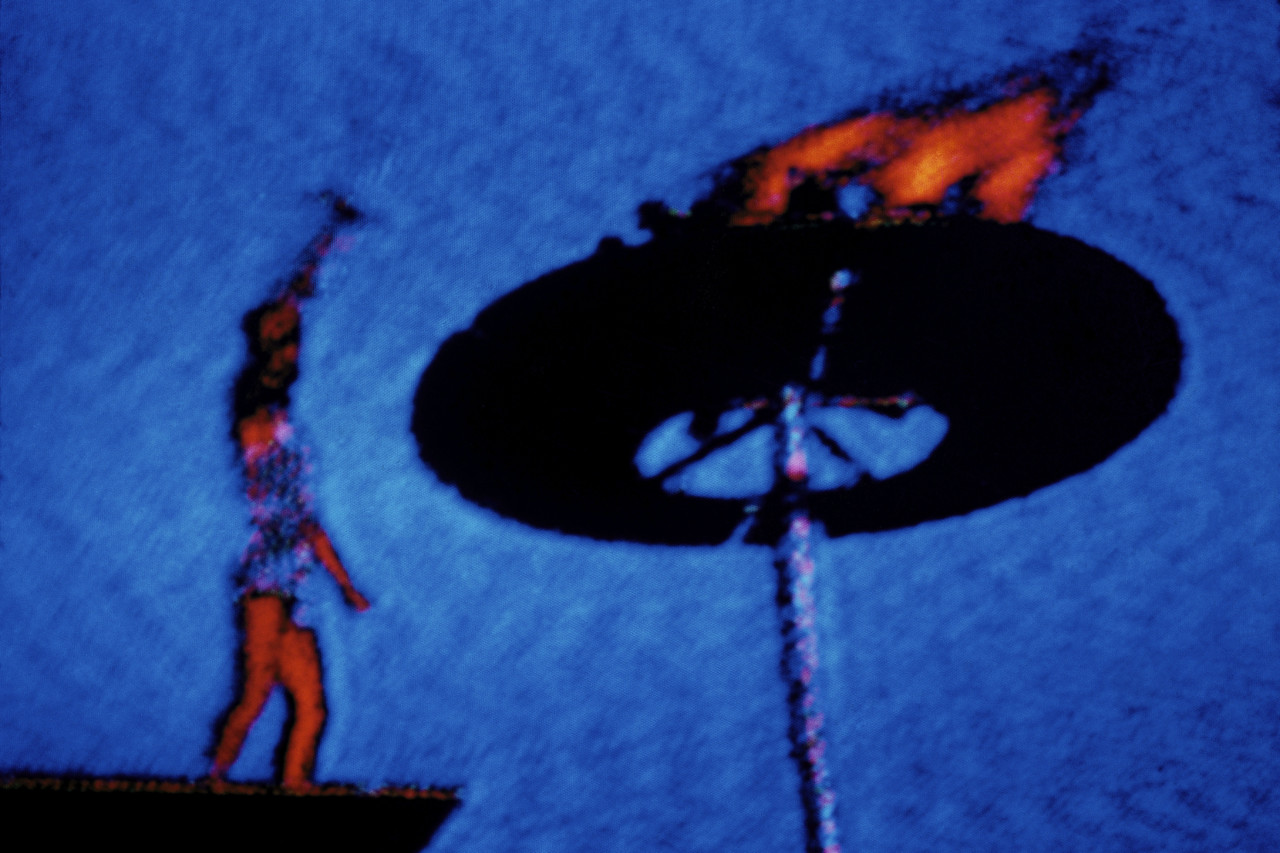

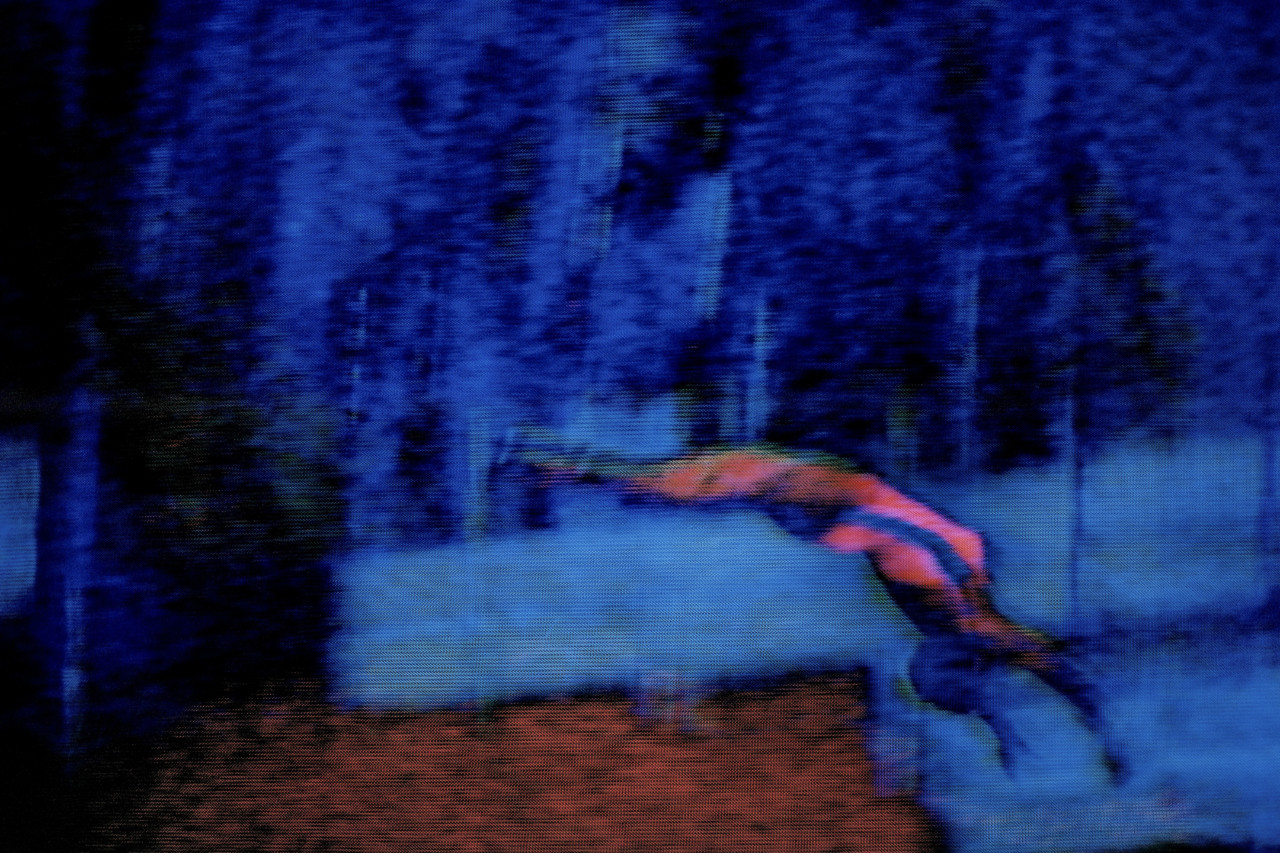

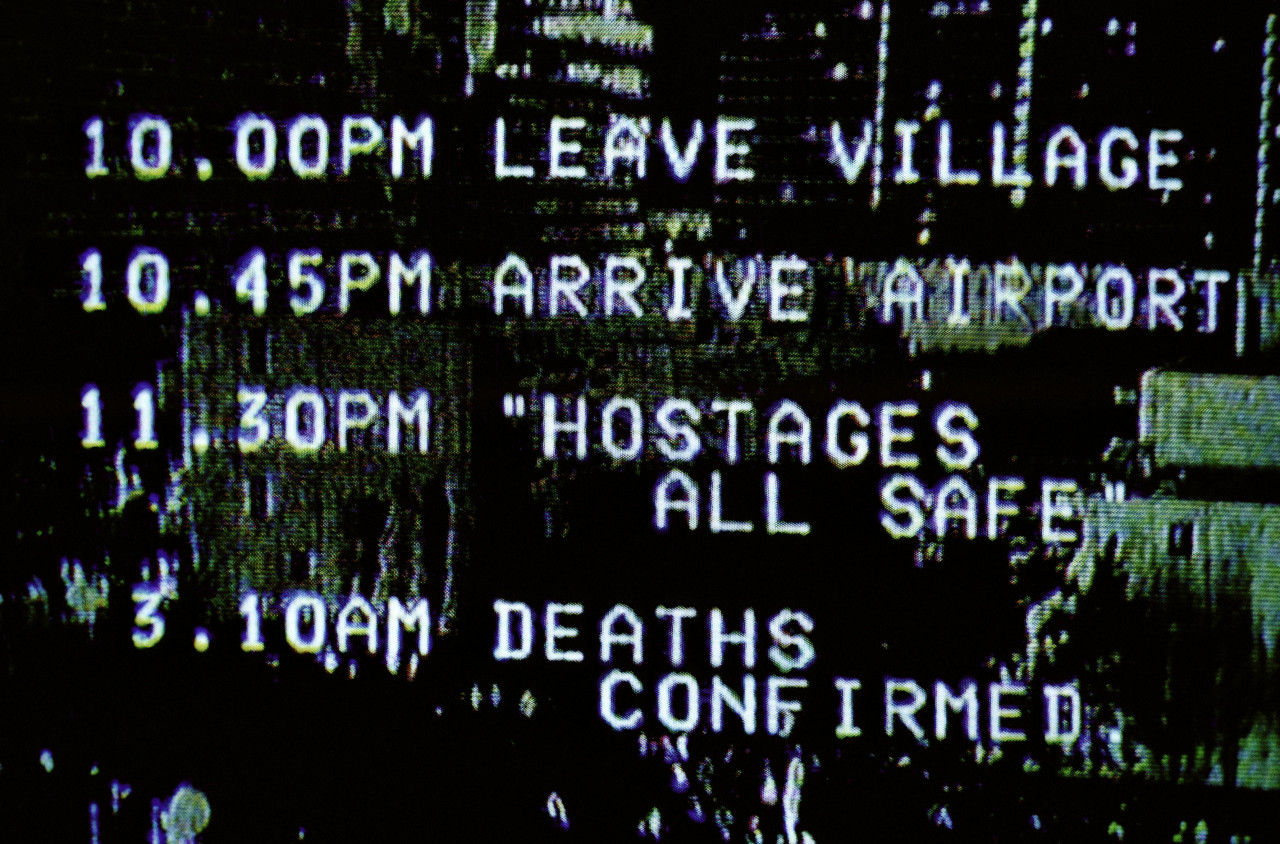

“When I was living in London in the early 70s there was a crazy television set in my house. By playing around with the antenna and tweaking the controls I could suddenly obtain fascinating colours. This led me to spend a couple of months following the latest news as it happened, from the first Apollo flights to the Munich Olympic Games, as well as American and English television series and ads. It made me see the world in a different way and question the ever-growing global influence of television throughout the world,” says Harry Gruyaert of his series of abstracted stills of momentous world events, including this series from the 1972 Olympics, which history remembers as the Munich Massacre: eleven Israeli Olympic team members were taken hostage and eventually killed, along with a German police officer, by the Palestinian terrorist group Black September.

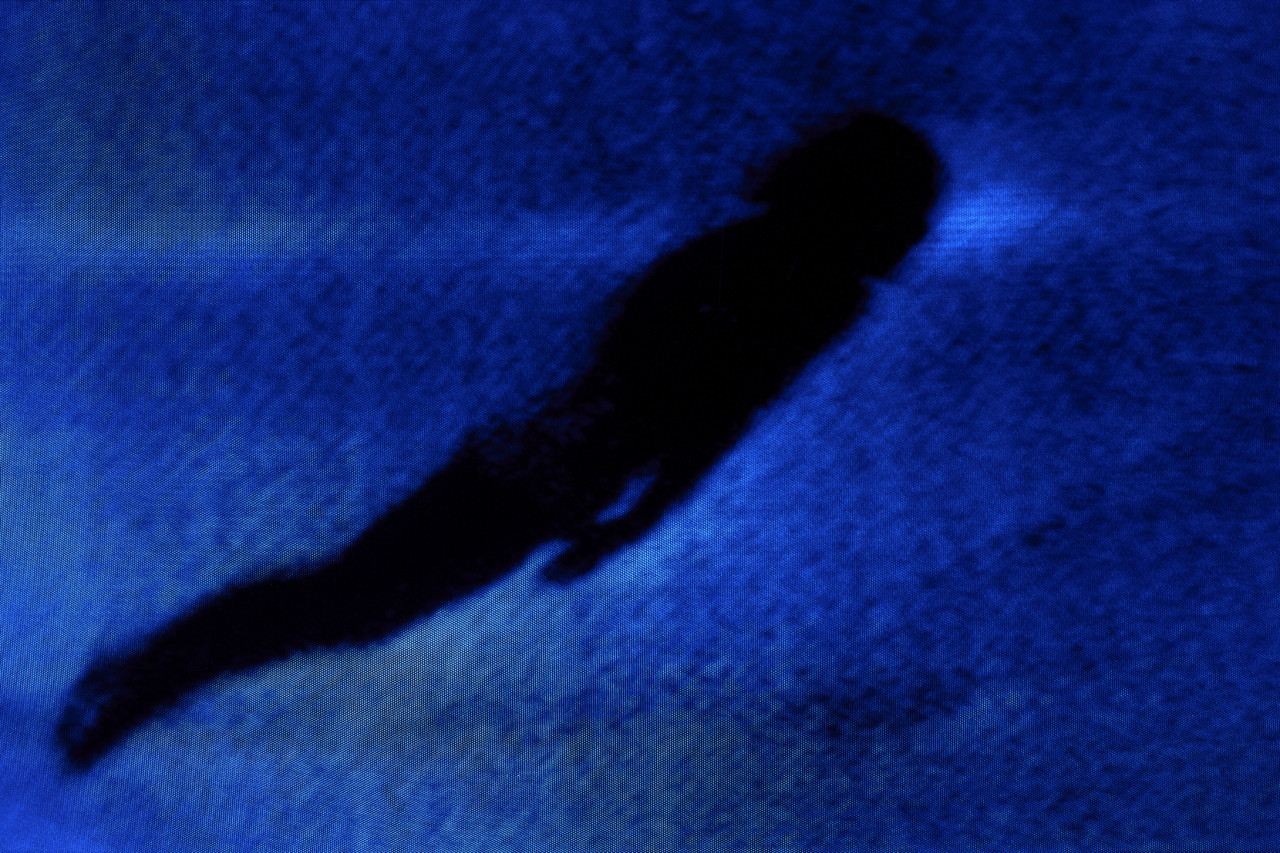

His vivid images, distortions of the pictures flickering through the cathodic tube of his television, have a universal appeal, yet they are very much rooted in a single moment in time, capturing both the universality of the sporting achievement viewed through the medium of television, and its utter banality. This 1972 study also became a document of one of the early instances of rolling news as updates on the unfolding terrorist attack took the place of sporting imagery. In the slideshow above we see chronological text headlines with news of hostages taken, then updated to ‘deaths’, chillingly sandwiched between warped outlines of athletes.

He continues: “In those days VCRs didn’t yet exist, let alone the ability to freeze frames or to rewind. I was, therefore face to face with current events – live – camera in hand and sometimes very close to the screen so I could frame things differently.”

Described as a “radical challenge to the conventions of press photo”, Gruyaert cites the influence of Pop Art, notably Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein and Nam June in inciting in him a desire to frame the reality of consumer society with both insight and a sense of humor. When the series was exhibited at the Robert Delpire Gallery in Paris in 1974, to great controversy, Gruyaert found himself at a defining moment in his career: he had never felt more like a photojournalist, yet the form of the work could not have been further from the current affairs photo stories of fellow photojournalists.

“I had become a kind-of bedroom reporter, confronted with the ‘society of spectacle’, in front of this factory of universal thought: it’s probably the only time in my life when I truly felt like a ‘photojournalist’, as close as I would ever be to the world’s terrible reality: the machine, sabotaged by flamboyant disrespect, is put back in its place and its message becomes absurd and alarming.”

Today, looking back at these shadows of bygone sporting stars and forgotten prowess, we instantly recognise the fuzz of a flickering television set, so far from the crystal-sharpness of today’s LED television displays. The single frames that Gruyaert so uniquely captured, examined, and displayed recall the universal moment of a global phenomenon witnessed by millions in their living rooms: a shared human experience that transcends location and time.