Between 1988 and 1994, photographer Alex Webb took pictures in all parts of the state of Florida. A northerner born in San Francisco and raised in New England, Webb never felt drawn to the state as many Americans do for different reasons. He never toured the world of Disney’s EPCOT as a child, didn’t have an ageing relative to visit in Sarasota, hadn’t heard a distant jangle of a street guitarist covering Stevie Nicks’s “Dreams” as the sun set over the ocean in Key West’s Mallory Square. Instead, he came to Florida through an interest in the Caribbean and Latin America, where he had photographed extensively before.

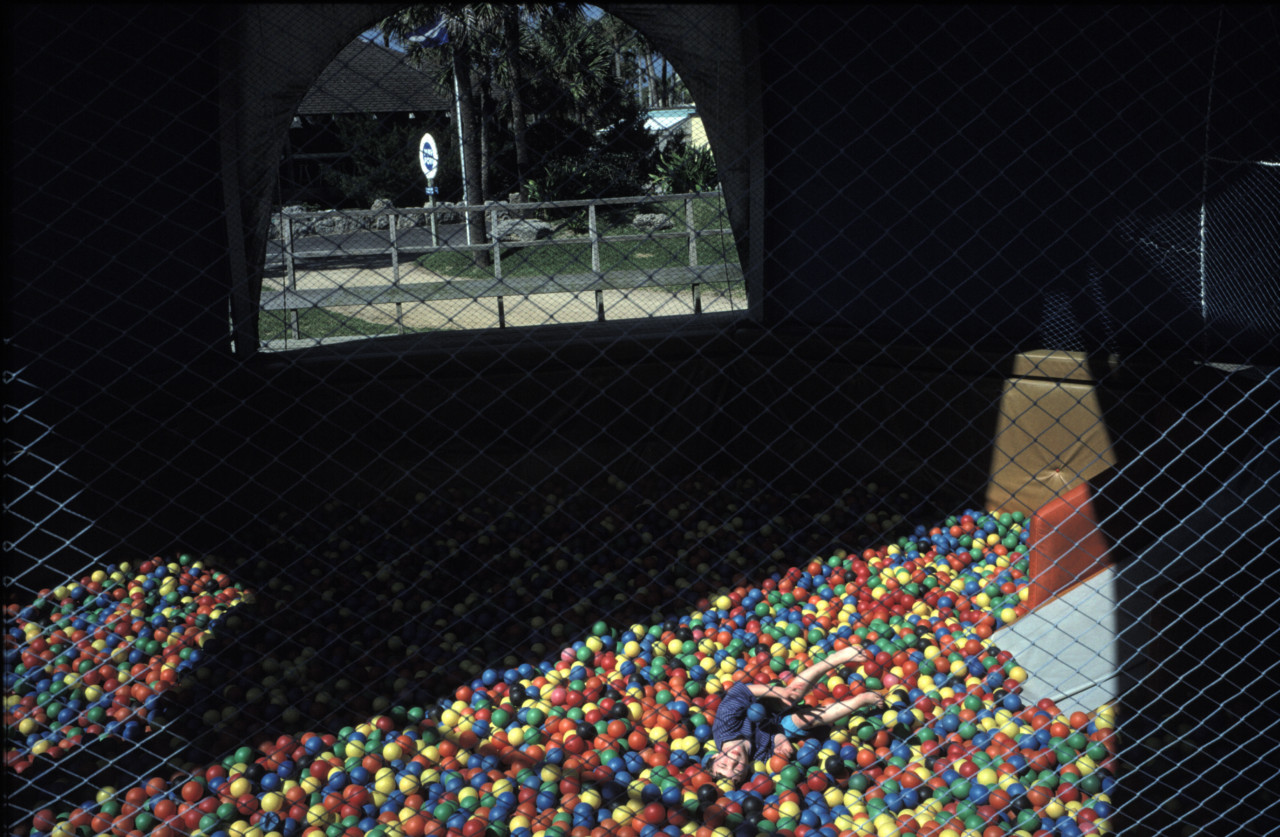

“Whether in Port au Prince or San Salvador, St. George or Santo Domingo, so often I heard the same wistful dream,” Webb writes in the book’s afterword, “the gleaming white city of Miami, the possibility of work (…) and the physical cleanliness and supposed order of North American life.” With subjects ranging from the elderly to leisure and tourism to migrant workers, the book From the Sunshine State published by The Monacelli Press in 1996 encapsulates Webb’s Florida into a sort of poetic atlas of instances. The shifting weather and widely varying locations in combination with the range of Webb’s subjects and photographic approach create a dizzying, multifaceted hurricane of color and contradictions—intimacy in public, beauty in desolation, a sense of time that seems elastic, artifice as daily life. In Webb’s Florida, the small is writ large and the large is writ mini-golf- sized. It would be a perfect fantasy, were every bit of it not true.

There is also a lot of levity in this work—even joy—but I chose to ask Webb about some of the more foreboding photographs in the series.

You seem to be just as interested in cloudy days in Florida, in your book From the Sunshine State. Was there some psychological darkness you wanted to show about the place? I’ve heard it called “god’s waiting room” before.

AW: I don’t go to a place with a preconceived notion of what I am going to find. I let my experiences with the camera guide me. The “psychological darkness” that you refer to was what emerged as I photographed. I wasn’t looking for it, but clearly it’s something that I responded to and kept responding to—deeply. I often find something a little ominous in Florida. Some kind of trouble or—at the very least, uncertainty—seems to lie just below the surface. Perhaps it’s because many come to Florida in search of youth, sex, sun, or, for immigrants, some version of the American Dream. And most are woefully disappointed.

I read that you came to this work through an interest in the Caribbean, but wanted to show more than Caribbean immigrants in Florida. When you were photographing these immigrants, how were their lives different from the people you photographed in Haiti, Jamaica, or Guatemala? If it is even possible to generalize…

AW: It’s pretty hard to generalize about this. I imagine that it must be daunting and overwhelming for most immigrants to leave the familiarity of home for the United States. I can’t imagine having to deal with such changes in one’s life: confronting different mores, perhaps a different religion, an utterly different environment, and—if in the U.S. illegally—remaining as invisible as possible. I have often felt that the immigrants I’ve met in Florida—and elsewhere in the U.S.—live in some kind of ever-shifting borderland, with one foot in their original culture, and another in the United States.

But, as a more specific example: the lives of the Jamaican migrant cane cutters that I photographed in Florida were very controlled and delineated. Flown specifically to the U.S. to work for sugar companies, they lived in barren barracks and worked in the fields all day, with little else to do in their off-hours in the poverty-stricken town of Belle Glade. A very different existence, I suspect, than the one back home in Jamaica.

"As a photographer who generally walks the streets, I love those private moments in public spaces, when people reveal their vulnerability"

- Alex Webb

"There were certainly times when I was intensely conscious of the passage of time"

- Alex Webb

Within the pictures, there seems to be a wistfulness in the way you are looking at technologies and surfaces that even then must have seemed dated: plastic payphone booths as planets in space, the wide lapels of polyester suits at the Cuban American Social Club etc. I will go even further to suggest that there is something about time here—the little girls on Disney World’s 1930s New York backdrop, the woman dressed as a flapper next to a cutout of Marilyn Monroe, the women waiting for the bus, the lifeguards waiting for an emergency. Is there something about time you were conscious of when you were making the work?

AW: I’m not sure. I generally work so unconsciously that I am not always certain of the dividing line between my rational awareness and my instinctual visual response. I often feel I learn most about what and why I am photographing when I look at the photographs after I’ve taken them. That said, there were certainly times when I was intensely conscious of the passage of time—for example, while photographing in Marineland, which clearly calls to mind a whole other era. However, I would never have noticed the wide lapels at the Cuban American Social Club, if you hadn’t pointed them out to me.

There is a picture of an elderly couple wearing white, sitting on a bench in Saint Augustine. It looks like it’s about to storm and they are both staring off into separate distances. On a purely emotional level, what are some of the things you think this work is about?

AW: As a photographer who generally walks the streets, I love those private moments in public spaces, when people reveal their vulnerability. I hesitate to speak too much about what a picture like this one—or what the work as a whole— might be about. Is the impending storm suggestive of the end of these elderly people’s lives? Perhaps, but I prefer to let the viewer discover that—or whatever other interpretation he or she may come up with. It’s fascinating to see the range of responses that different people have to the same image. It’s something I love about the ambiguity of photography…

Yes, sometimes learning the backstory of a photograph ruins its mystery. But still I’m tempted to ask. There are a couple of pictures of a fire behind some sports fields.

AW: It was a brush fire. I found it so intriguing that people continued to play soccer, either ignoring—or seemingly fascinated by—this massive fire. It all seemed so odd, so inexplicable— so Floridian.

One of my favorite pictures in the book is of a funeral, with a hand reaching out of the open grave. How did you come to be at the funeral?

AW: This was the funeral for a young black man, Clement Lloyd, who was unarmed when killed by a policeman, an incident that set off the Miami riots of 1989. So a slew of journalists, photographers, and TV crews were present. Oddly enough, no one else seemed to notice the gravedigger still in the grave.

Mini golf courses also feature prominently in this work and share some of the surreal qualities of the disembodied hand.

AW: I like the idiosyncrasy of the often family-owned miniature golf courses. So many tourist sites—especially newer ones—seem so corporate, so slick, so predictable. But the particular design of each miniature golf course tends to reflect the quirks of their owners, who are also often their creators—fantastical octopi, giant snakes, dinosaurs, Moorish architecture…

Have you photographed in Florida since this book came out? What do you think has changed?

AW: I’ve photographed some in Florida since the book, but not consistently or coherently. However, I am currently working on a new project photographing a variety of U.S, cities, and I may well return to Florida in the next couple of years to photograph some of its cities.

What interests you about photographing in a vacation place?

AW: I’m always intrigued by people at play, when they seem to be relieved of the burdens of work, when they act more spontaneously and often more surprisingly. But—for whatever complicated reason—I’m often conscious of the darker side, of more disturbing notes, perhaps suggesting that even at leisure, we can’t escape the long shadow of suffering.

Published as part of Magnum’s summer series of stories: ‘Life by the Sea: Exploring identity through society at leisure and the pursuit of pleasure’. See the rest of the stories from the series here.

Browse the Life By The Sea poster and fine print collection on the Magnum Shop.