Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Vision of Matera

As the Italian town celebrates its European City of Culture status, we revisit the Magnum co-founder’s photographs of Matera from critical moments in its history

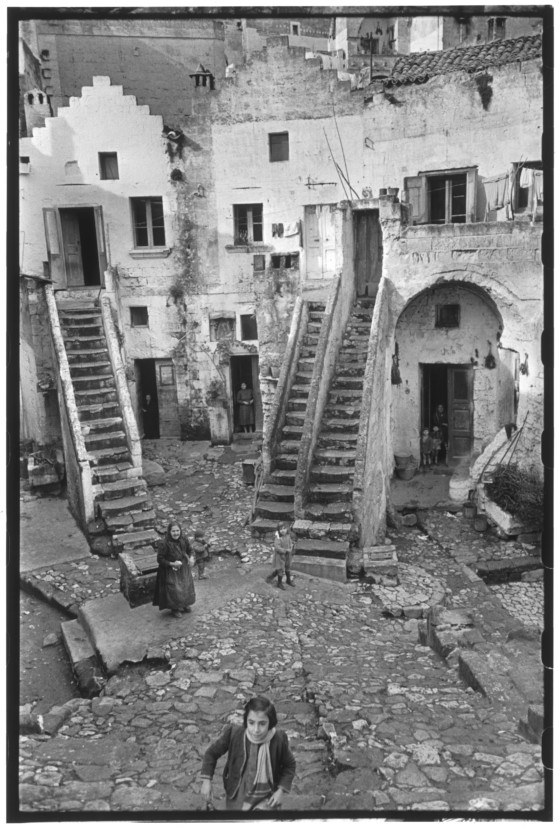

Henri Cartier-Bresson first arrived in the Italian city of Matera in 1951, commissioned to photograph the historic locale by Italian authorities. His aim was to capture Lucania, the area of Southern Italy where Matera is located, and famously depicted in the paintings of Italian artists Carlo Levi and Rocco Scotellaro. Cartier-Bresson created a comprehensive portrait of the region, photographing Matera itself as well as nearby Potenza, and their respective satellite towns.

In 1985 Cartier-Bresson donated his images of Matera to the Italian city. The collection comprises images made over two time periods: 1951-’52 and 1972-’73. Carmela Biscaglia is the Director of the Documentation Center Rocco Scotellaro and Basilicata, which records post-war life in the region. Below, in light of Matera’s status as European City of Culture for 2019, we republish her words from the original catalogue that marked this important acquisition.

It all began with a donation made by Henri Cartier-Bresson to the Comune of Tricarico (Matera) in 1985, through his friend Rocco Mazzarone, in the memory of Rocco Scotellaro, a young poet Cartier-Bresson met on his first visit to Lucania but who died prematurely in 1953.

The Foundation has 26 photographs that not only hold a significant position in the 20th century photographic panorama of Lucania, but which are images taken by Cartier-Bresson in 1951 to 52, and in 1972 to 73, two critical phases in the region’s 20th century history. They are accompanied by a commentary by Mazzarone himself, the intellectual and doctor with a profound knowledge of Lucania, who accompanied the French photographer during his visits to the region. The correspondence between the pair is testament to their deep friendship. This was a crucial link for Cartier-Bresson to break into that world, in keeping with his belief that “whether you move or stay put, you need establish yourself, you need to build close relationships, supported by the community in which you find yourself”. Cartier-Bresson viewed photography as an experience that, by investigating the values of existence, allowed for a fusion between oneself and others. In his own words, “It is by living that we discover ourselves, in the same moment that we discover the outside world”.

"Whether you move or stay put, you need establish yourself, you need to build close relationships, supported by the community in which you find yourself"

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

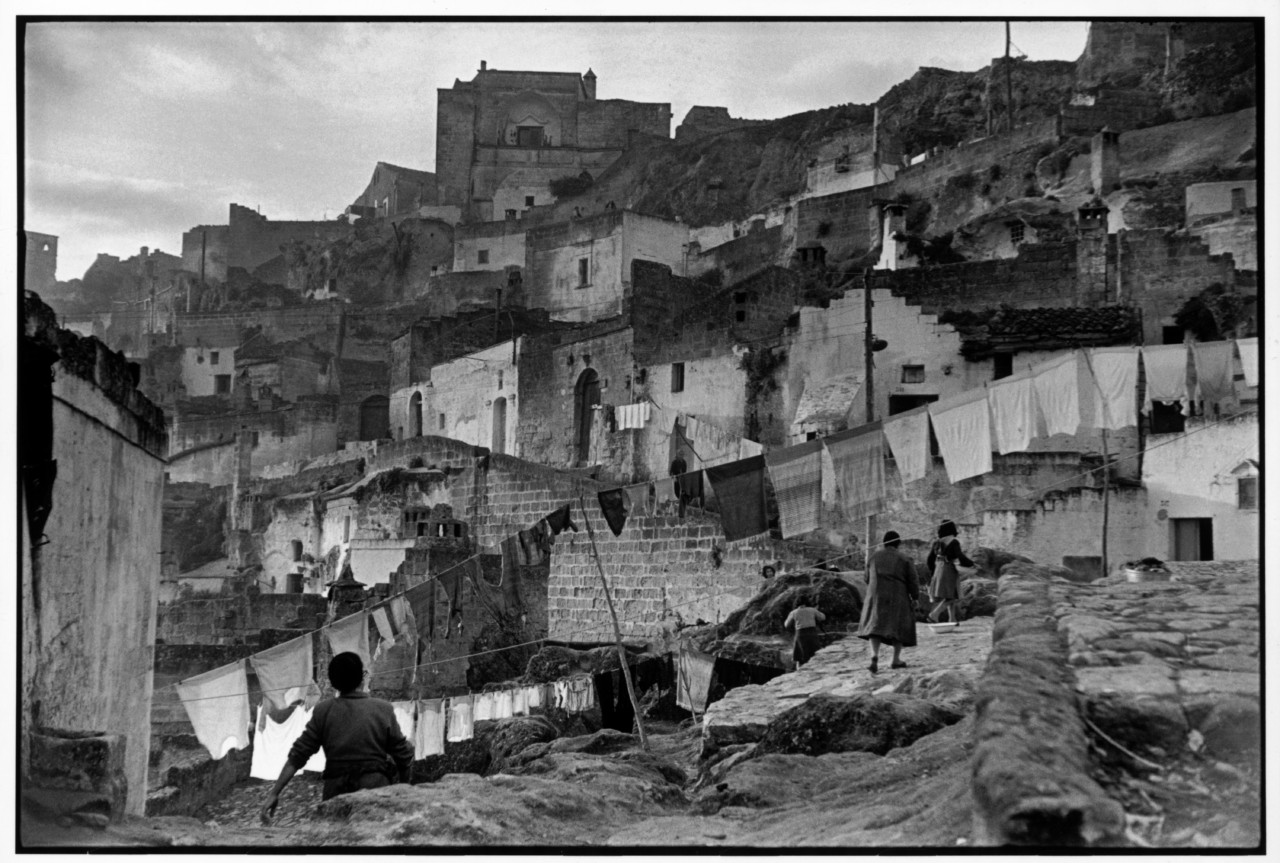

Cartier-Bresson arrived in Matera at the end of 1951, sent by the UNRRA-CASAS Prima Giunta which had set up the historic Commission for the study of the city and agriculture in Matera, in collaboration with Italy’s National Urban Planning Institute (Istituto Nazionale di Urbanistica) headed by Adriano Olivetti. The photographer made initial contact with the group of specialists including Riccardo Musatti, Giuseppe Isnardi, Tullio Tentori, Francesco Nitti, Rocco Mazzarone and Friedrich George Friedmann (the German-American philosopher who was the inspiration behind the project), and worked with them, providing a splendid visual analysis of life in the Sassi, to be published with the group’s report.

The Commission, which continued until 1954, provided the anthropological basis for understanding the Weltanschauung of those working the land, providing 38 indications for urban planning in Matera, inspired by the Movimento Comunità (introduced to them by Olivetti) and in the rural settlements such as La Martella and in new neighbourhoods. These were to be built following the law on the redevelopment of the Sassi passed by Alcide De Gasperi, and their creation would involve the greatest architects and urban planners of the time, such as Luigi Piccinato, Ludovico Quaroni and Carlo Aymonino.

This was the context in which Henri Cartier-Bresson’s first photo reportage on Lucania came about, to which he credits the human, professional and artistic journey that led to his volume Les Européens (1955). It was a context typical of the region in the early 1950s, with a whole series of further research projects carried out by North American scholars, projects sponsored by the Parliamentary Commission into poverty in Italy and how to combat it, and reportages by other photographers such as Ernst Haas, David Seymour, Fosco Maraini and Arturo Zavattini. The presence of each of these groups transformed the region, turning it into a hotbed of research after the huge success of the English translation of Christ Stopped at Eboli. The bestseller, published in English in 1947, brought international attention to the plight of the Sassi as part of the new, dramatic state of under-development in Lucania, in an Italy brought to its knees by war.

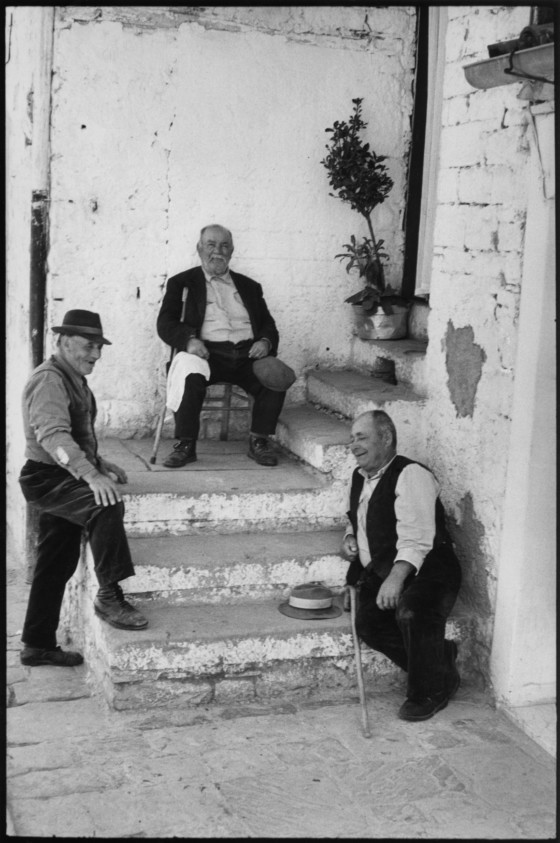

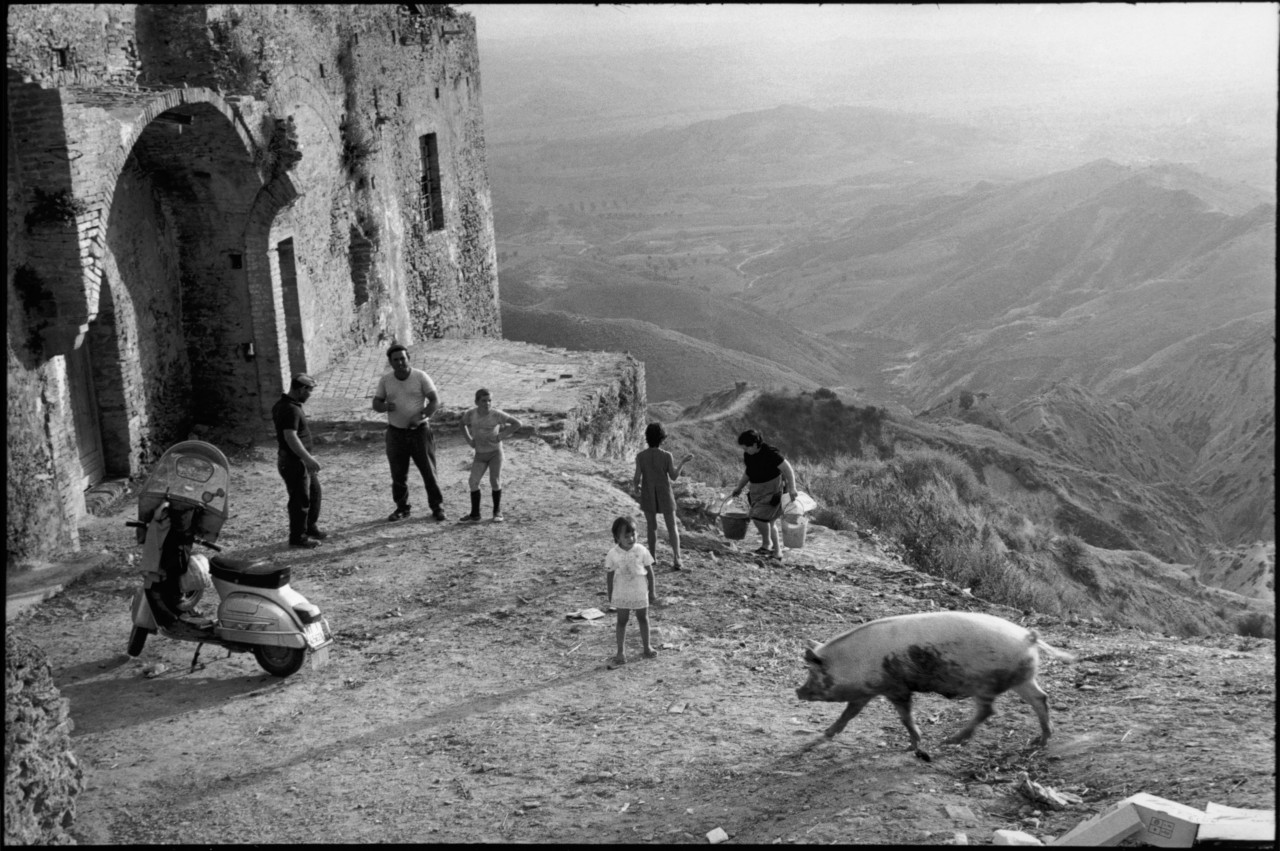

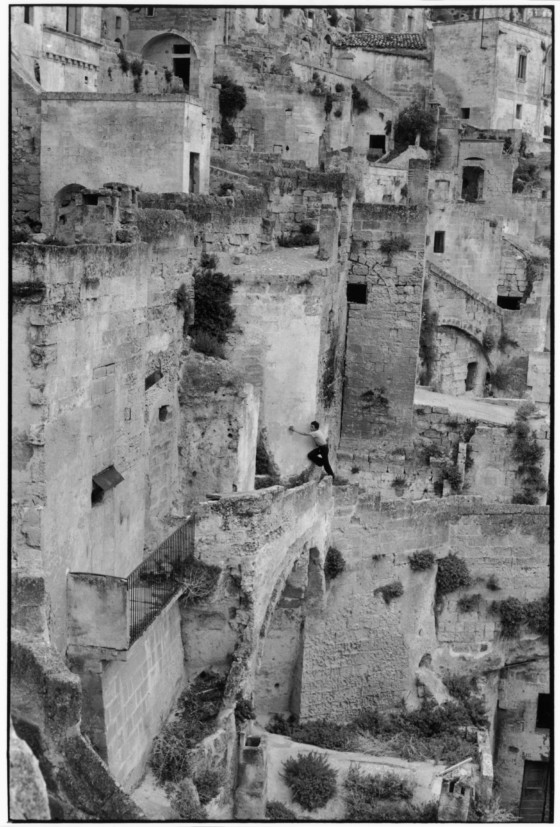

In the photos taken between 1951 and ’52, it is with great respect for the people and landscape that Cartier-Bresson captures the Lucania of Levi and Scotellaro showing its first signs of change. It is at this point that the difficult living conditions in the region began to improve, thanks to the redevelopment projects aimed at moving the population of the Sassi into more hygienic and dignified homes, at improving literacy and assigning land from the large estates to poverty-stricken peasants in the hope this would enable them to meet their aspirations.

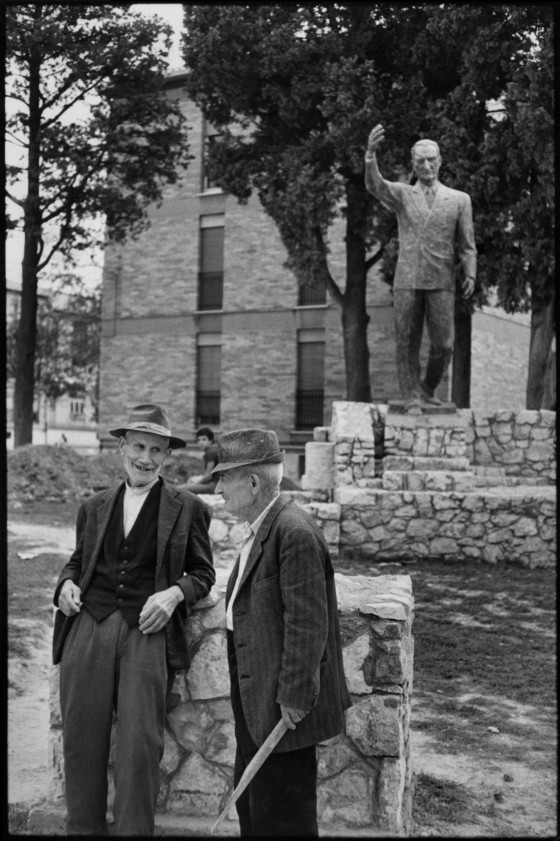

Iconic of this is the emblematic photo that shows, in the background of one of the crowded ceremonies held in Lucania at the time to allocate smallholdings following agrarian reform, a peasant showing his thanks by giving an anachronistic “Roman salute”. Indicative of the repercussions healthcare and improved nutrition would have on the incredibly high level of child mortality is the photo that catches the moment in which a doctor administers medicine to a newborn infant. These photos are typical of Cartier-Bresson’s work in the post-war period, when the social objectives of his work had grown significantly.

"It is with great respect for the people and landscape that Cartier-Bresson captures the Lucania of Levi and Scotellaro showing its first signs of change"

- Carmela Biscaglia

However, as we can see from the Lucania images, the artist did not renounce his “affectionate curiosity for the timeless models of human behaviour and their various incarnations, which are always unique”. His emotional involvement when he came into contact with poverty in Lucania was significant, to the point that on July 6th 1974, he put aside his reporter’s scientific detachment and wrote to his friend Mazzarone, «me lasse une tristesse, car me sens si attaché au pays et aux gens que nous avons connu» [“leaves me sad, because I feel so attached to the country and the people we have met”]. Upon his return to Lucania twenty years later (twenty years that were marked by the gulf between the last phase of subsistence living and the problems involved with nascent industrialisation), Henri Cartier-Bresson uses his second reportage to a social and economic reality that had been changed beyond recognition.

"The photographer created a comprehensive panorama of the region"

- Carmela Biscaglia

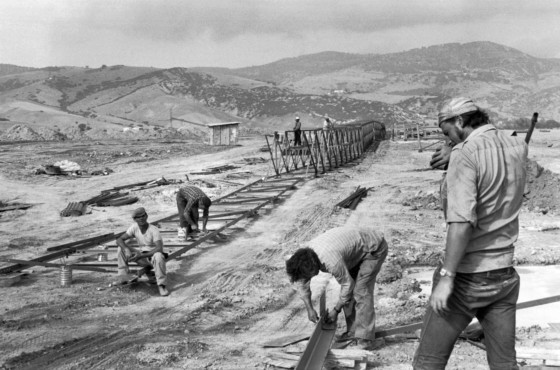

There were new industrial areas in the Basento valley, where methane deposits had been discovered, vast areas of swampland around Metaponto had been cleared, malaria had been eradicated and irrigation systems put in place that would pave the way for profitable and highly specialised farming. The photographer created a comprehensive panorama of the region: of Matera and its surrounding towns of Stigliano, Ferrandina, Aliano, Craco, Pisticci, Scanzano, Sant’Arcangelo and Grassano, of Potenza and the towns of Rionero in Vulture, Acerenza, Tolve, Vietri di Potenza, Pietragalla, and Avigliano.

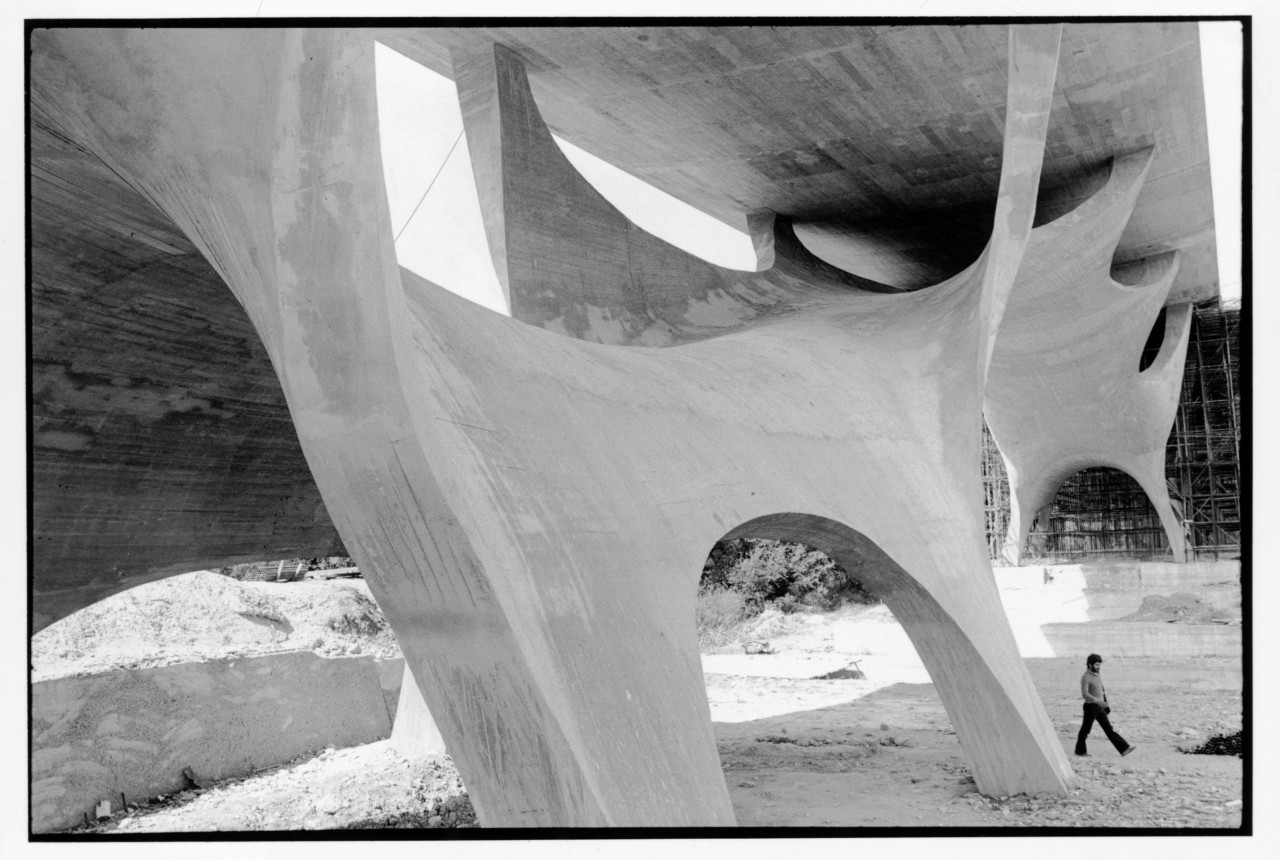

He captured the lives of people in these towns and the countryside, the work of the ancient manor farms and the modern smallholdings in Val d’Agri, the new farming methods in and around Metaponto, the widespread cultural debate within the ancient libraries, the new realities for young and old, whilst taking in the transformations brought about by factories, viaducts and cement dykes and bridges – think of the image of the bridge in Potenza, designed by Sergio Musmeci, to connect the city to its industrial estate. They worked holistically, showing the region a way out of dignified, cave-dwelling poverty and a subsistence economy along the stark ravines of Pisticci and Aliano, towards the new opportunities offered by industry and the modernisation of farming.

"Cartier-Bresson captured the contrast between ancient and new traditions in Basilicata"

- Carmela Biscaglia

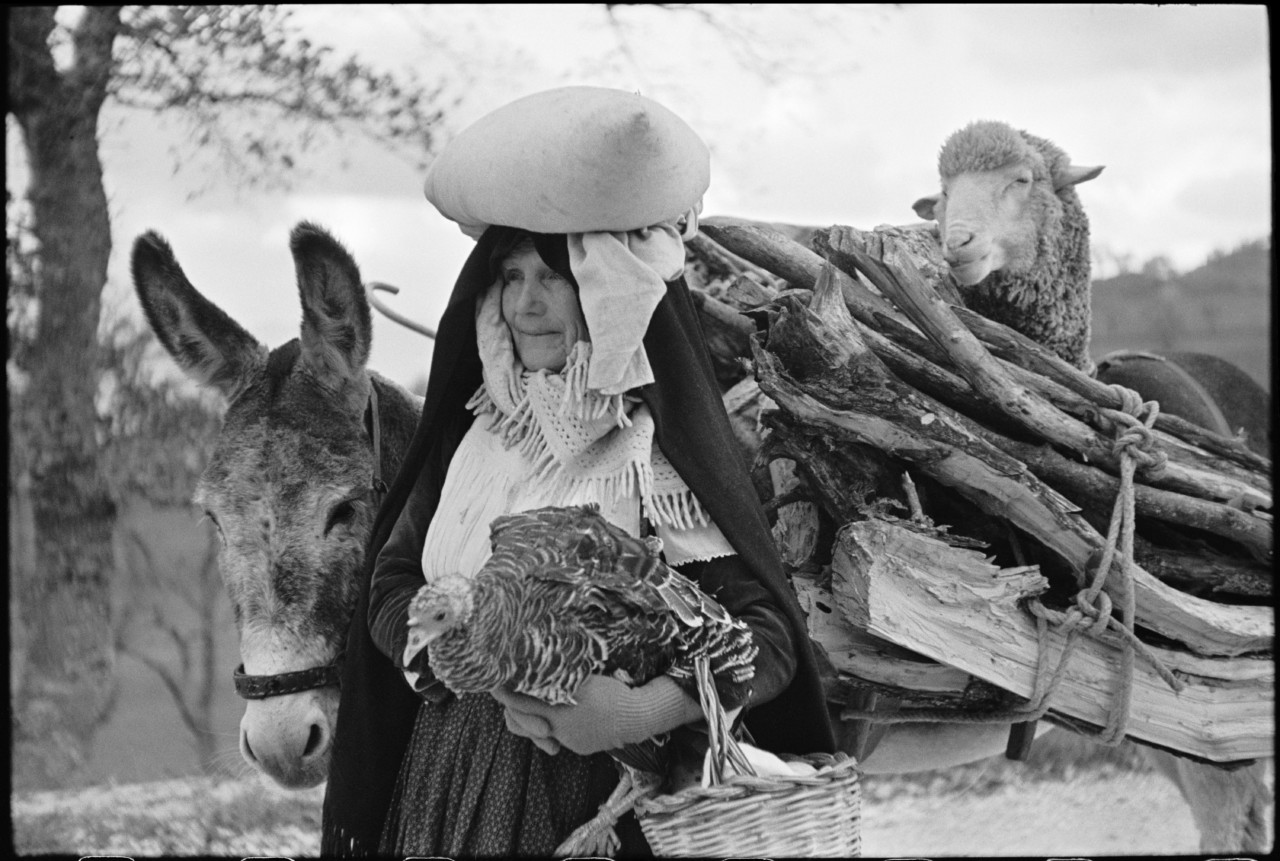

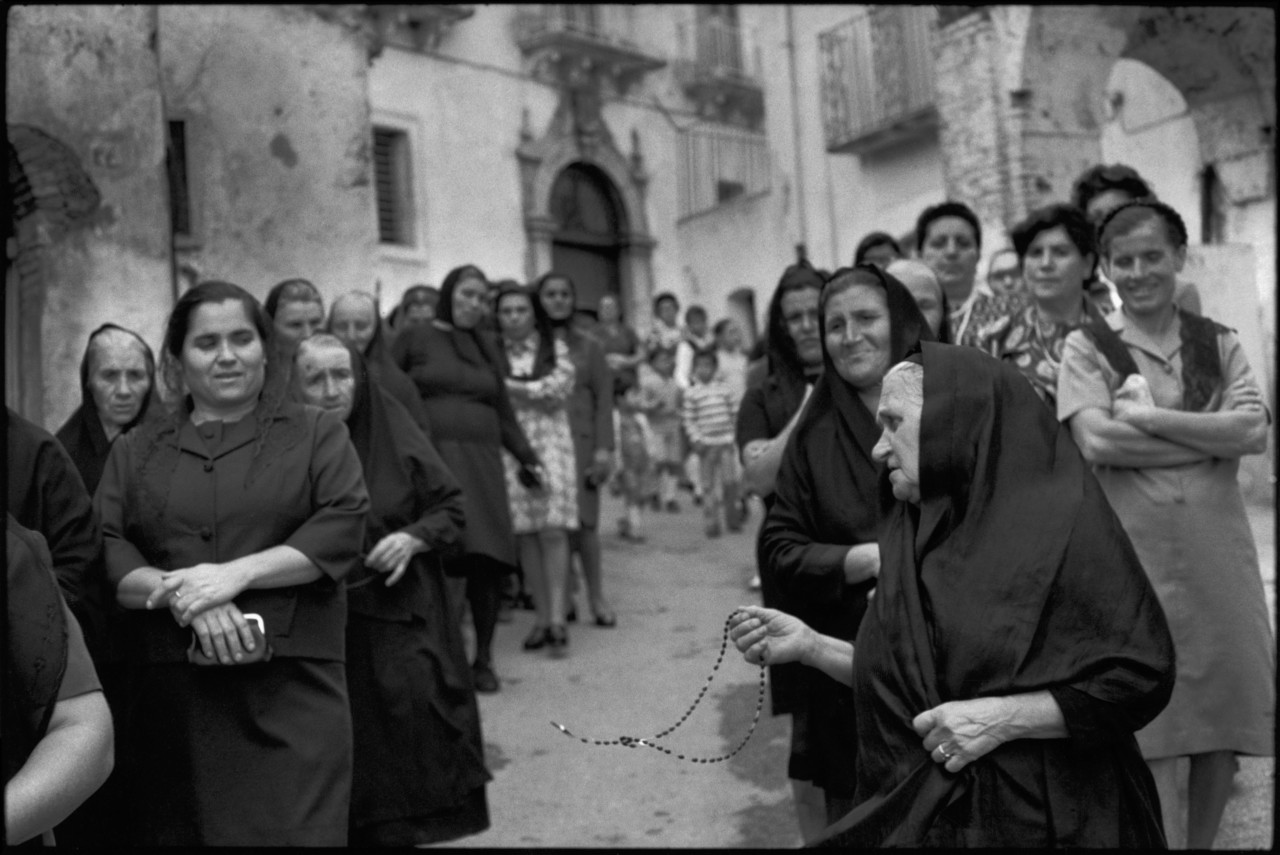

With the lens of his Leica trained on the conflict between old and new, men and women, rich and poor, the powerful and the weak, individuals and groups, groups and crowds, without ever betraying his ability to penetrate the soul of the individual, Cartier-Bresson captured the contrast between ancient and new traditions in Basilicata, the combination of Pagan myths and Christian traditions, archaic work tools alongside electrical appliances – that of the plough and the donkey, the faithful companion of the peasant’s hard work, and the tractor and motor car of the returning immigrant. The great photographer did not fail to capture the new masses of young men, whose aspirations for work were not met and who were readying themselves for a new exodus, or the ruling class that continued to distribute favours, weak trade unions and political parties who were nothing but, in the words of Rocco Mazzarone, “groups of families and migrant clientele”, from the moment big decisions continued to be taken elsewhere.

One afternoon in 1973, Mazzarone was accompanying the great photographer to the Basento valley, where the first stone of the many settlements that would never be built was to be laid. He asked him to photograph the “conceited face of one of those involved”, but Cartier-Bresson replied that he would only do so if the opportunity arose. A curious spectator and careful witness even in those circumstances, he approached reality discreetly, on tiptoes, watching those images of his Lucania “with a velvet glove and a falcon’s eye”. Impeccable in their composition, geometrically balanced, from a chain of shapes organised instinctively by his gaze, these images provoke irony or sadness, they ask us to take stock and provoke emotions of human sympathy and the same joy that he must have felt at the moment of taking the shot.

Excerpted from the exhibition catalogue of La Lucania di Henri Cartier-Bresson: immagini di una terra ritrovata, Milan (2015).