A Russian Journal

John Steinbeck and Robert Capa’s seminal book offers an account of everyday life in the Soviet Union during the Cold War

A Russian Journal, (1948) attempts only “honest reporting, to set down what we saw and heard with editorial comment, without drawing conclusions about things we didn’t know sufficiently,” according to its author John Steinbeck. The book developed out of Steinbeck and Robert Capa’s desire to produce an eyewitness account of the everyday life in Stalin’s Soviet Union. The pair journeyed along the so-called Vodka Circuit – Moscow, Kiev, Stalingrad and Georgia – for forty days between July 31 and mid-September 1947, documenting the people and landscapes they encountered.

Following the end of World War II, growing tensions between the Soviet Union, under Stalin’s Communist rule, and the United States, culminated in the beginning of the Cold War. For most, the war was largely invisible; devoid of the battlefields and fighting of traditional warfare. Intrigued by what lay behind the Eastern Bloc’s ‘Iron Curtain,’ Steinbeck and Capa were determined to venture into these unknown territories and record the everyday lives of their inhabitants. With Western newspapers saturated by daily reports about the activities of the Eastern Bloc, the pair set out to author an account of the region that would offer an alternative perspective of it, centering on its people and free from any historical context, political overtones or in-depth analysis.

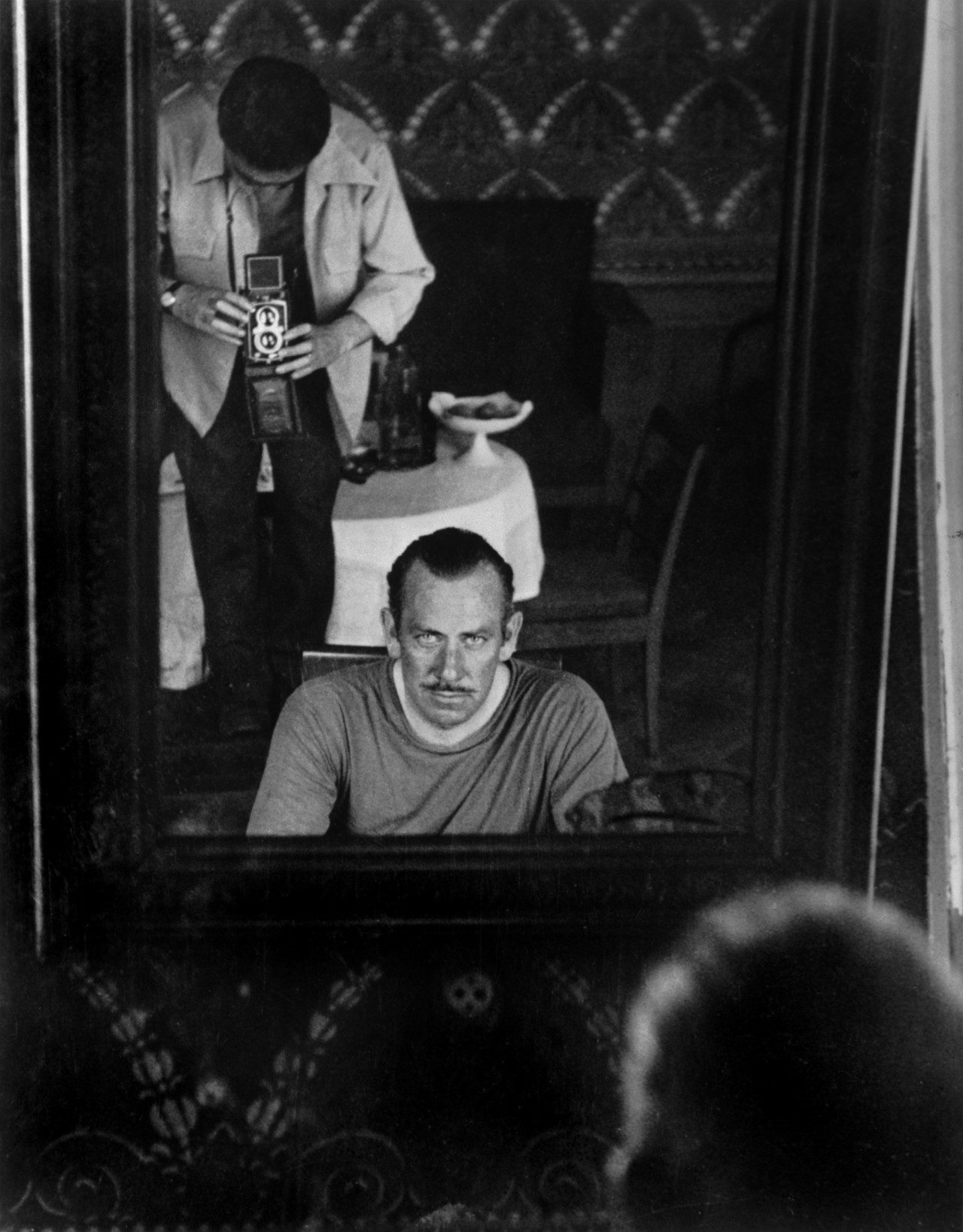

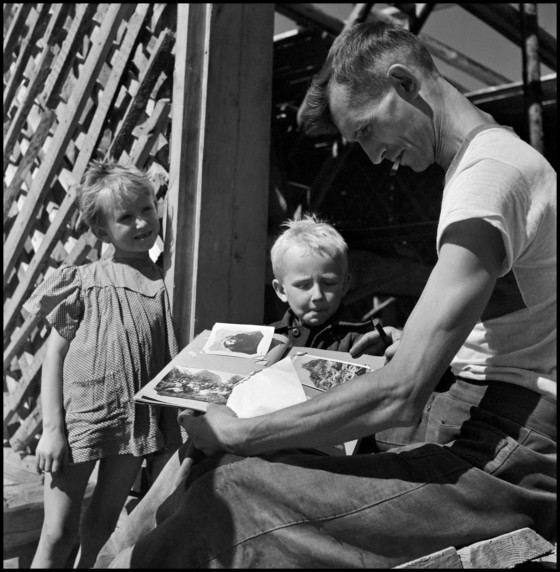

Neither Capa nor Steinbeck naturally gravitated towards collaborative endeavors. The affinity between their creative approaches, however, resulted in what was both of their most successful collaborations. Capa returned from the trip with almost four thousand negatives, and Steinbeck with several hundred pages of notes. Dedicated to privileging the individual portrait over a comprehensive narrative, Steinbeck and Capa were united in their desire to record the everyday details of Soviet life and the unique people they met during their travels. Writing about the photographer following his premature death in 1954, Steinbeck praised Capa’s ability to do this: “He could photograph motion and gaiety and heartbreak. He could photographer thought … Note how he captures the endlessness of the Russian landscape and one single human. See how his lens could peer through the eyes into the mind of a man.”

"Note how he captures the endlessness of the Russian landscape and one single human. See how his lens could peer through the eyes into the mind of a man"

- John Steinbeck

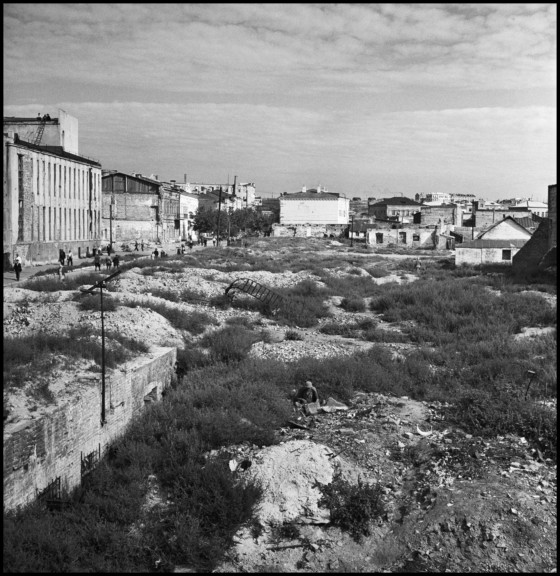

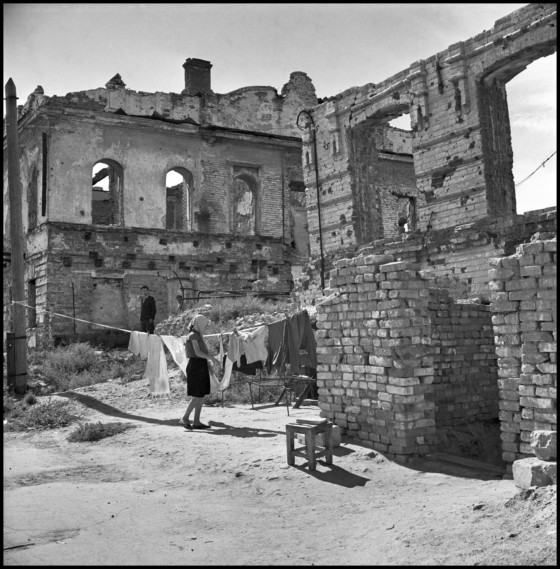

The pair left to endless warnings about the dangers they would encounter, after receiving sponsorship from the New York Herald to fund the trip. They arrived in Moscow in the summer of 1947. Far from encountering the monstrous society that had been described to them, Capa and Steinbeck were impressed by the unrelenting hope and strength of a people who had survived against all odds, emerging from the horrors of war to lives governed by the repressive and dictatorial regime of Stalin. From the tired and stern-faced inhabitants of a newly built Moscow, to the incredible spirit of the Georgian people and the beauty of their region, through image and text, A Russian Journal captures the unique characters of the places and communities they visited, and the innumerable peculiarities of the Communist State.

There had been no camera coverage of the Soviet Union by an American for decades. Steinbeck recounts how Capa brought with him a multitude of photographic equipment, including duplicates of almost everything in case any of it might be lost. A war photographer by nature, Capa, however, struggled to be excited by the recovering landscapes of the Soviet Union.

Throughout the text, Steinbeck makes reference to Capa’s difficulties, devoting a single chapter, A Legitimate Complaint, for the photographer to complain openly: “the hundred and ninety-million Russians are against me. They are not holding wild meetings on street corners, do not practice spectacular free love, do not have any kind of new look, they are very righteous, moral, hard-working people, for a photographer as dull as apple piece … My four cameras, used to wars and revolutions, are disgusted, and every time I click them something goes wrong.” Nonetheless, Capa encountered moments of inspiration, producing a body of work that documents the region from his unique perspective.

"My four cameras, used to wars and revolutions, are disgusted, and every time I click them something goes wrong"

- Robert Capa

Steinbeck and Capa’s trip was arguably only approved by the regime in the hope that their book might improve relations with the United States. They were accompanied at all times by a state-sanctioned official who, for the most part, dictated their itinerary. Thus the pair were mainly presented with a rose-tinted version of the social realities of post-war Soviet cities; meeting with carefully selected leading intellectuals in Moscow and Georgia, and select members of the peasantry in Ukraine. For the most part, they were denied visits to factories and working class districts, and any photographs taken by Capa that documented too much topography were censored by Soviet officials before the pair returned to the US. The majority of Capa’s negatives and Steinbeck’s prose however made it through, and, collated as A Russian Journal, present an invaluable historical record of a significant moment in recent history.