A Russian Journal Retold, Part 1: On Aeroflot to Moscow

Following in the footsteps of Robert Capa and John Steinbeck, Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak and writer Julius Strauss embark on the first leg of a Russian journey

In 1947, just as the Iron Curtain fell across Europe, John Steinbeck, the American writer, and Robert Capa, renowned war photographer, made a six-week journey through Stalin’s Russia. The following year they published A Russian Journal, a book that painted a sympathetic portrait of ordinary Soviets. Seventy years on, Julius Strauss, a former long-serving war correspondent, and Thomas Dworzak, the president of Magnum Photos, retraced their footsteps.

At first blush the world they flew into in a sleek new Aeroflot jet bore little resemblance to Stalin’s Soviet Union. But soon, Strauss and Dworzak realised that the parallels with the early Cold War were more poignant than they imagined. Russia was in the grips of vigorous militarism and strident nationalism and seeking to re-establish spheres of dominance abroad. Shiny new museums glorified the Soviet past with multi-media displays and smart military parades showcased reconstituted Tsarist-era regiments. Officials railed against what they see as the West’s effete liberal values and its perfidy and aggression. Meanwhile Ukraine and Georgia were struggling to fight off Moscow’s unwanted advances and steer their countries westwards.

Following in Steinbeck and Capa’s footsteps, Strauss and Dworzak found themselves in a patchwork of new states, hopscotching across a jagged frontline where the writ of the Kremlin and the West met. And as Strauss and Dworzak moved from Russia to the frontlines in Ukraine to the frozen conflicts of Georgia they realised that the glitzy and outwardly confident Moscow of today hid darker truths. Only on one thing do both pro and anti-Russian officials in the region agree. A new war was already underway – a struggle that pitted Putin’s Kremlin, the Russian Orthodox Church and the revamped Red Army against those who believe in NATO, the European ideal, and western liberal values.

On a sunny-cloudy afternoon, almost exactly 70 years after John Steinbeck and Robert Capa landed in Moscow in a beaten-up American warplane, we arrived on a sleek Aeroflot jet.

Thanks to a mix-up we were at the front of the airplane and the stewardesses were attentive in their beautifully-cut orange uniforms with subtle hammers and sickles emblazoned on the cuffs.

We had set out to follow the footsteps of Steinbeck and Capa. In 1947, a little over two years after the Soviets stormed Berlin, John Steinbeck, the American writer, and Robert Capa, the renowned war photographer, made a six-week trip through the Soviet Union at Moscow’s invitation.

Steinbeck wrote that they set out to ignore the anti-Soviet prejudice they found in the West and the political debates raging around Moscow’s intentions and document instead the lives of ordinary Russians. We were also here to take the pulse of modern Russia at a time of heightening tensions with the West.

The changes, of course, since the height of the Cold War, had been immense. The strictures of High Stalinism in no way compared to the political and economic freedoms enjoyed by Russians, Ukrainians and Georgians today.

But at some levels the resonances with what Steinbeck and Capa had found were uncanny. The Moscow we arrived in was now, as then, bristling with militarism, national myth-making, and anti-western sentiment.

Russian officials spoke passionately against what they claimed was western warmongering, perfidy and moral decadence.

Statues, memorials and tributes to the Second World War (the Great Patriotic War to the Russians) had always been well-represented in Moscow, but now it seemed the war had become the foundation stone of a towering edifice that was a muscular new Russian identity.

I soon lost count of the number of new museums and exhibitions showcasing Russia’s war-time sacrifices and recreating the storming of the Reichstag by the Red Army.

“They have been searching for a historical narrative that unites the nation and they have found it in World War 2,” an old friend who has lived in Moscow for 25 years told me.

“The message is: we fought fascism in Germany back then and saved the world, and we are fighting fascism in Ukraine today. But instead of being thanked for it, we are being criticised.”

I spoke to a churchman, a university professor, a strip club owner, army veterans, trendy young Muscovites, pensioners and art connoisseurs.

And almost everywhere people told me that Russia, under the guidance of Vladimir Putin, was rediscovering what it meant to be Russian and forging its own path. The vast majority approved.

“I wasn’t pro-Putin before he took back Crimea,” a well-respected academic at the journalism department at Moscow State University told me. “But I am now.”

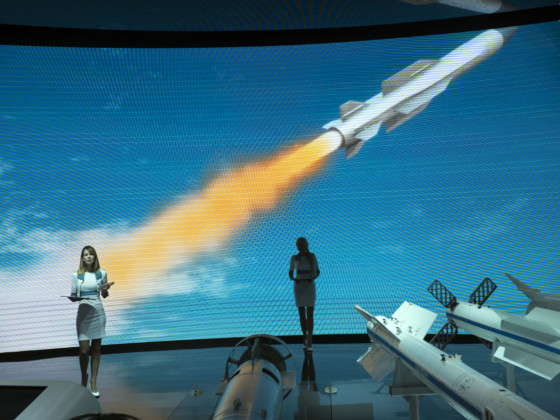

The drumbeat of this new militarism was everywhere. At an air show on the edge of Moscow gunmetal fighter jets were streaking across the skies while Russian ladies in high heels and pencil skirts marketed new rocket systems to Iranian buyers.

On Mayakovskaya Square a designer shop owned by the Russian military was selling high fashion with Red Army motifs.

At a Miss Moscow competition the contestant that stole the show was a young graduate from the FSB, the modern variant of the KGB. She performed in camouflage, repeatedly flinging two burly mock assailants to the ground to show off her martial prowess.

It was patriotic, militaristic, and sexy. And the judges roared their approval.

A few days later at Victory Park, cadets were being inducted into the Preobrazhensky Guard, an elite Tsarist-era unit recently reconstituted by the Kremlin. A deep voice intoned the victories of the Soviet Army during WW2.

Museums celebrating 20th century history, once shabby places of academic interest and quiet reflection, are now dominated by noisy patriotic-themed multi-media displays replete with Disney-like heroes and villains.

In Sevastopol in Crimea, to mark the annual Day of the Navy, a military extravaganza was laid on for the populace the like of which I had not seen before. For hours helicopters, frigates, multiple rocket launchers, and fighter planes fought mock battles, spewing noise and smoke.

If the Kremlin was stoking the fires of nationalism on the home front, it was active abroad too.

We visited the studios of RT, the foreign arm of Moscow’s television news programming, that pushes the Kremlin’s new agenda around the world.

This year the agency, which already has services in English, Spanish and Arabic, will be opening a new channel in French, an audience that is seen as ripe for anti-American messaging.

Befitting the times, sport and athleticism are also high on the new Russian agenda. In Red Square we watched as hundreds of men shadow-boxed. Svetlana, 27, wearing tight jeans embossed with a golden gun and skulls, told me: “This makes people feel more united.”

Even as Russians I spoke to approved of Putin’s brand of bare-chested nation-building, many railed against what they saw as the effete values of the liberal west.

The smart owner of a television station and former investment banker told me: “Twenty years ago they decided that sodomy would be allowed here. But now things are changing. There are 30,000 new priests in Russia while in the West churches are becoming bars and discos.”

Of course, Putin’s with-me-or-against-me populism engenders opposition as well as support. Opponents are dealt with increasingly harshly.

I spoke to a young man who had spent three and a half years in prison for attending an opposition rally in 2012. “I can’t tell this to my friends here,” he said in a quiet voice over a coffee in an artsy Moscow bar. “I don’t want to let the others down. But, yes, I am scared.”