A Century of Seeking Solitude

100 years since Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan first gained independence, Lawrence Scott Sheets writes about the struggle for, and legacy of, independence in the Caucasus mountain countries

Lawrence Scott Sheets is an author, analyst, and journalist who has spent nearly 30 consecutive years in the former Soviet Union, much of them in the Caucasus mountain countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Here, he explores the history of the region, as it marks 100 years since they gained independence.

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia have just formally marked 100 years of independence. Even this date is somewhat misleading; that first independence came about as a result of the meltdown of the Russian Empire. That “first” independence lasted only 3 years before the Bolsheviks re-established control, and the Soviets replaced the Romanov dynasty as the masters of the Russian Empire. It would be 70 years before the three republics, always some of the most reluctant constituent parts of the USSR, again stirred towards independence.

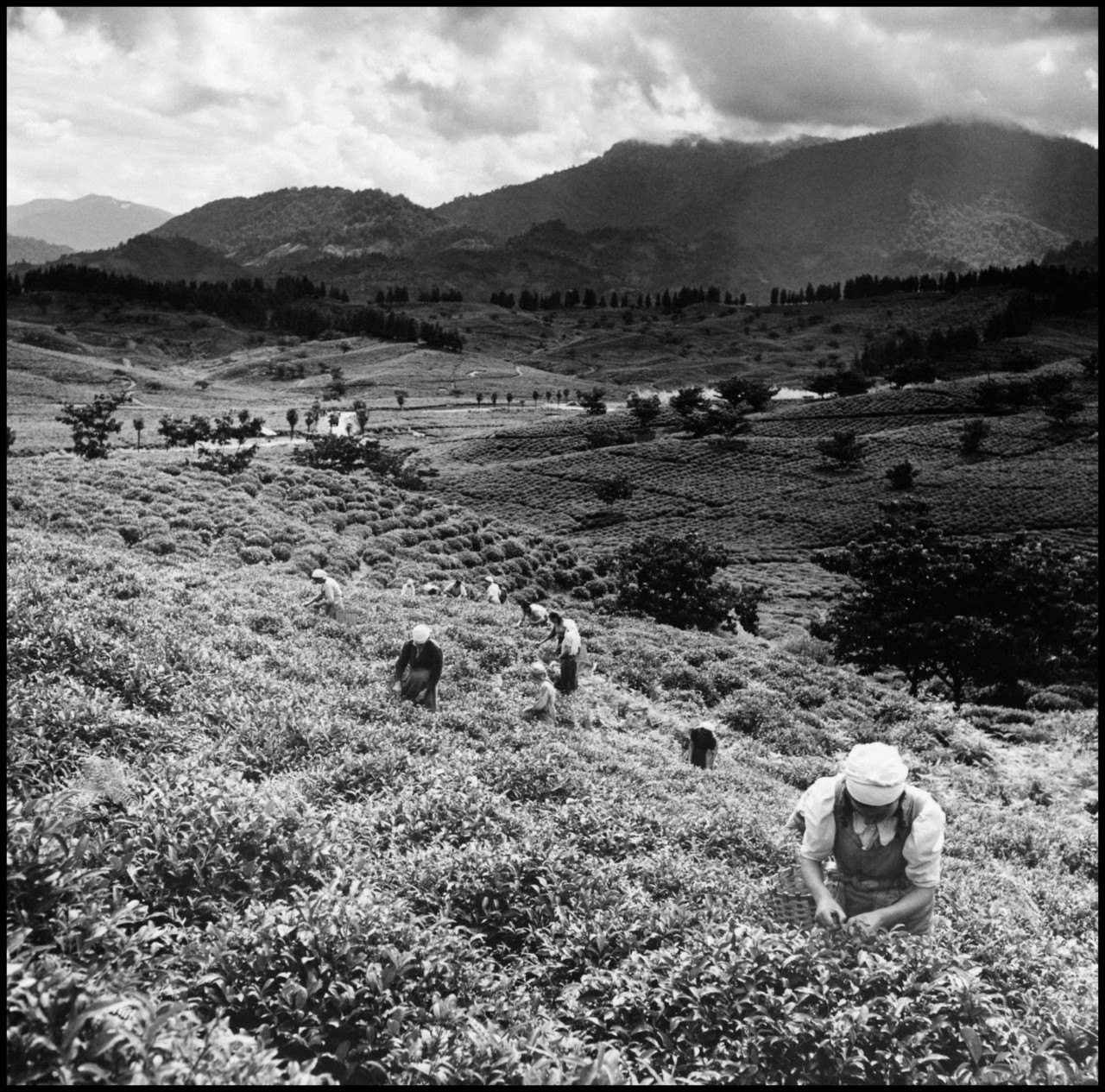

Magnum’s archive embodies a unique and compelling collection of photos from a wide range of the most famous pictorial documentarians ever to delve deep into this incredibly complicated and culturally rich region, home to at least 40 languages and 4 main alphabets – this in a region of less than 20 million people. There are unforgettable everyday life images from Robert Capa during his travels with John Steinbeck during the Stalinist era of the 1940s, and Brezhnev-era images from all three countries during the 1970s, from the inside of medical clinics in Armenia, to the oil-rich Caspian oil fields of Azerbaijan.

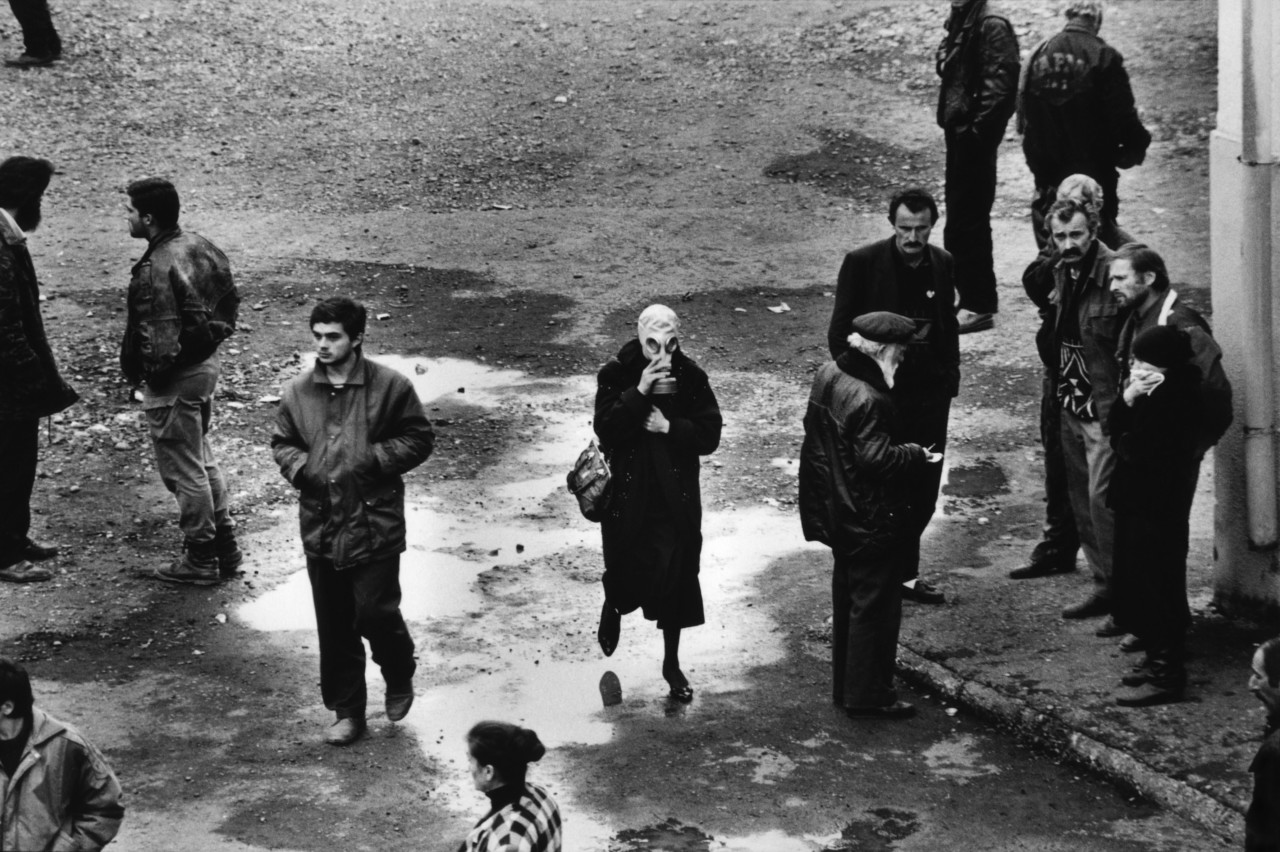

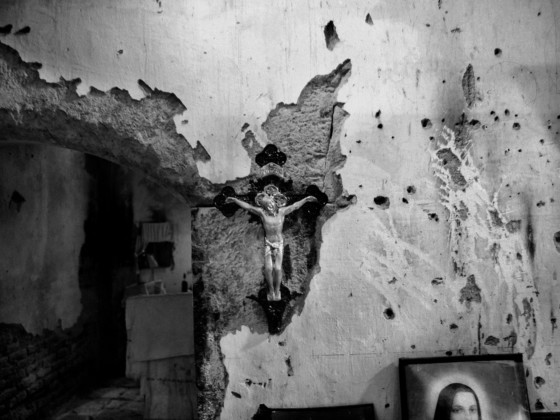

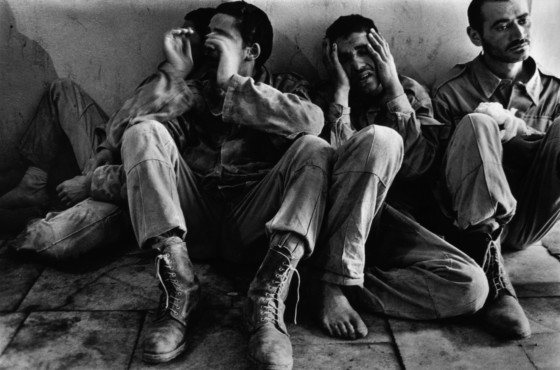

Perhaps the most stunning part of the collection deals with the period when the three countries (re) gained independence amid the Soviet Union’s own collapse during the late 1980s. This period was initially marked by euphoria. It quickly gave way to the grimmer reality of myriad armed conflicts, economic meltdowns, and general chaos. Armenia and Azerbaijan went into – and still are – in a state of war that started 30 years ago. The war has reached an unprecedented boiling point amid a meek international negotiating effort which has produced practically no tangible results. Soldiers, and sometimes civilians, are killed or injured on almost a daily basis. Almost all ethnic Azeris living in Armenia and ethnic Armenians living in Azerbaijan fled during the early days of hostilities. Then, Armenian forces caused approximately 600,000 Azerbaijanis to flee as they conquered district after district of Azerbaijan in the early 1990s, districts where no Armenians lived. Most still live as refugees, or in the favored bureaucratic parlance, internally displaced persons.

Georgia immediately found itself confronted with two separatist uprisings that had been brewing under the surface for decades. In 2008 the country would find itself in a full-scale conflict with Russia, which sponsors and backs the separatists.

The Capa works of the 1940s have been complimented by contemporary greats like Magnum’s Thomas Dworzak, who documented each of the many conflicts in the region during the 1990s and up to the present, as well as the beat of everyday life during these turbulent times.

The 100th anniversary has of course been met with the requisite military parades, commemorations, and celebrations, despite the pall cast over the region by uncertainty and conflict.

There are, of course, good reasons to celebrate such a short-lived independence period. During this time, for instance, Azerbaijan became the world’s first democratic Moslem state. Women were given the right to vote.

Armenia came about less as a product of a national liberation struggle than as a result of the bloody events of the end of the Ottoman Empire, and the new Armenian state was established on territory where formerly relatively few Armenians had previously lived.

Civil war also decimated Georgia in 1991-1992, reducing the center of the lovely capital, Tbilisi, to a smoking ruin. The country became a poster child for the “failed state” label, and general anarchy. The economy went from one which was one of the most prosperous in the Soviet Union (aided, no doubt, by black marketeering, graft, and a captive market in citrus fruit, wine, and holiday beaches) to a basket case, where electricity was a luxury of 2 hours a day and armed gangs roamed the lawless streets. Georgia’s 1918 independence was led by a group of nationalist thinkers and writers, but this movement was easily crushed by inside forces and the inevitability of Russian military power to subdue the short-lived republic.

Having emphasized the irony and pain of the 100th “celebration” of the independence of these countries, it must be said that the future, as unclear and precarious as it is, looks much brighter. In Georgia, the rampant petty corruption, street crime, and marauding gangsters are a distant memory, replaced by a functioning state, even while the country is still locked in hostile relations with Russia. And the tourism for which it was famed during the Soviet era has returned with a vengeance, as an avant-garde tourist Mecca. When this author first arrived in 1992, there were only a handful of functioning hotels for a city of over a million.

Only the foolhardy dared venture out after dark. There were also just three restaurants which kept open after 6 pm. One was a basement haunt with the appropriate name “Palermo”, and one had to bang on a door and wait for a security guard to open a padlocked iron gate in order to enter. (It was quickly shut and re-padlocked as soon as you were inside). Now there are hundreds of hotels, hostels, cafes, and restaurants of all shades. Most ironically, Russians, despite the formal political hostility between the countries, comprise the most numerous number of guests. The country is simply too stunningly beautiful and exotic to shoo people away, whatever the uncertainties.

As for Azerbaijan and Armenia, the situation between the two countries remains explosive. Yet even so, Baku, the Azerbaijani capital, is unrecognizable from its decrepitude of three decades ago. Political issues notwithstanding, it has been airbrushed to a fine gloss, its classical European architecture cleaned and restored, money from its energy-driven economy having transformed its skyline along the Caspian shore. The war with Armenia, and the prospect of a new, major effort to liberate lands occupied by ethnic Armenian forces, hangs in the air like a Damocles sword, but seems to be of little interest to the average person, many of whom are busy getting quite wealthy.

Armenia is arguably in the worst shape. With its borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey shut by the war with all the concomitant economic consequences, mass emigration is ongoing. But even so the centre of the capital, Yerevan, has been shined up. Many young people seem oblivious to the 30-year old war or regard it as a somewhat amorphous conflict bequeathed to them by the older generation.

So the future, on this 100th anniversary, is fraught with very serious dangers, yet great promise. As one friend of mine recently said: “In 50 years, Azeris and Armenians will be marrying each other again, and the new generation will scoff at us as idiots for ever having gone to war”.