Robert Capa and the Spanish Civil War

A look back on Capa’s involvement with the Spanish Civil War on the anniversary of its outbreak

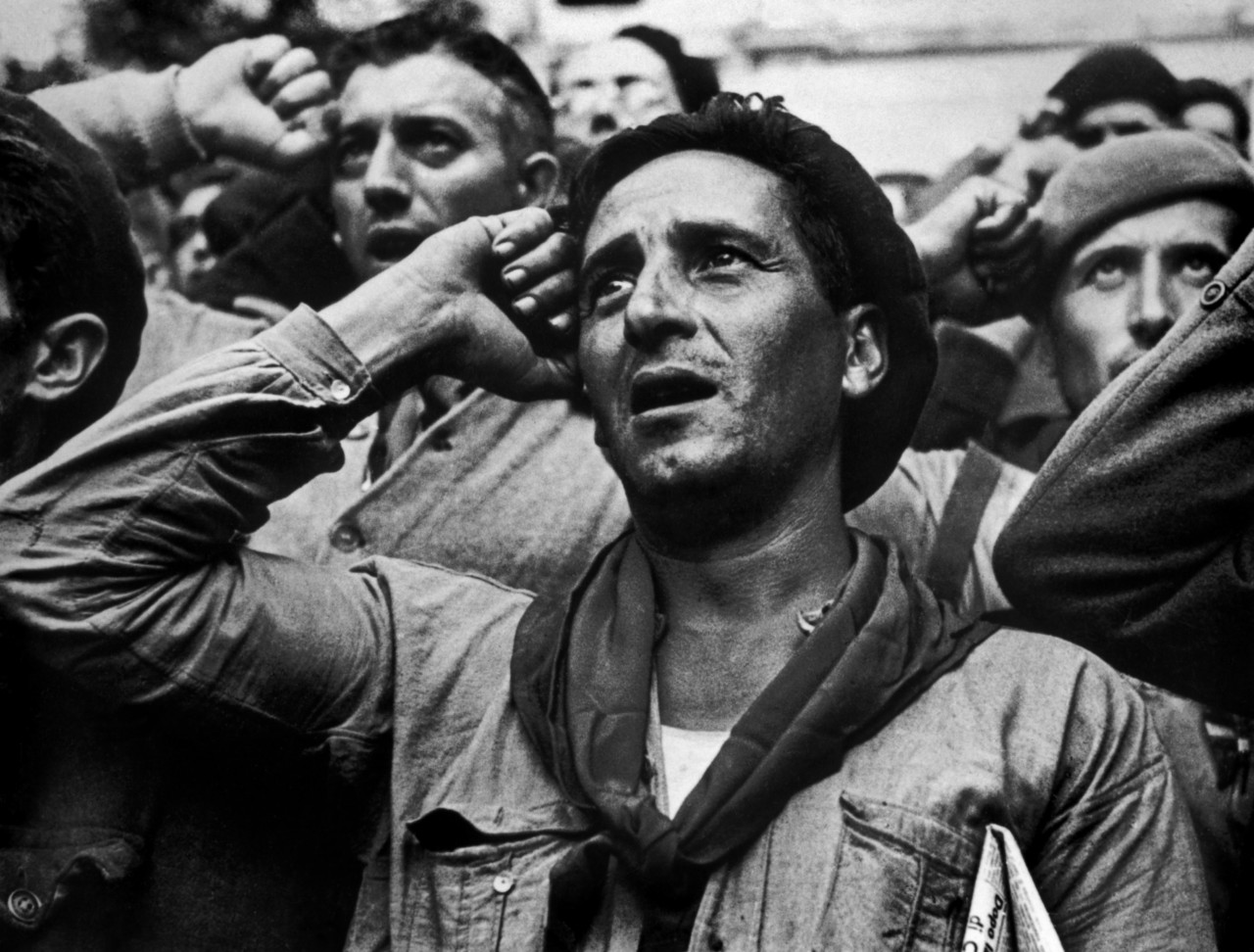

By the end of the Spanish Civil war in 1939 the socio-political landscape of Europe had not only altered, but the practice of war photography had also experienced some pivotal moments. The photographs taken by Robert Capa – before he went on to co-found Magnum – and his partner Gerda Taro captured the brutal realities of combat. Photographic coverage of the Spanish Civil War was an emotional investment for Capa; ideologically, he sympathized with the plight of the anti-fascist Republicans, consisting of the workers, the trade unions, socialists and the poor.

But Capa’s heart was also invested in his coverage for other reasons, with his partner Gerda Taro by his side for much of his time there. Their photographs became the enduring images of the Spanish Civil War. In an era when French publications usually gave no credit at all to photographers, French magazine Regards published Capa’s early images from his initial trip to Madrid proudly stating that it “sent one of its most qualified and audacious photographers to the Spanish capital”. In 1938 Picture Post introduced him, with his Spanish Civil War work, as “the greatest war photographer in the world”.

“The horrific tendency of modern warfare is to depersonalize. Soldiers can use their weapons of mass destruction only because they have learned to conceptualize their victims not as individuals but as a category – the enemy. Capa’s strategy was to repersonalize war – to emphasize that those who suffer the effects of war are individuals with whom the viewer of the photographs cannot help but identify.” – Richard Whelan, “Robert Capa in Spain”, in Heart of Spain, published by Aperture.

A New Identity

Before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Capa, then going by his real Hungarian name of André Friedmann, was a jobbing photographer in Paris, not earning a fabulous amount of money. His girlfriend Gerta Pohorylle came up with the character of ‘Robert Capa’, whom they would would tell potential clients was an esteemed American photographer. Pohorylle successfully convinced Parisian editors that it would be insulting to his reputation to buy his photographer for less than 150 francs each. It also allowed him to forge his own identity away from another working Parisian photographer of the time whose surname was also Friedmann. “I am working under a new name. They call me Robert Capa. One could almost say that I’ve been born again, but this time it didn’t cause anyone any pain,” wrote Capa in a letter to his mother. At the same time Gerta Pohorylle took on the surname Taro, after a Japanese painter living in Paris.

Capa’s biographer Richard Whelan wrote of how the two men – André Friedmann and Robert Capa – represented two sides of Capa: who he was and who he aspired to be. One “long-haired, unkept and unshaven Gypsy” and one “glamorous American” who his mother and Gerda – a woman who “sometimes called her lover André and sometimes Capa… as though they had a ménage à trois” wanted him to be. With his newly acquired – or invented – reputation, Capa was now earning enough to fund his travels more independently. It was a ploy that afforded them both the cachet and the freedom to traverse Spain to document the Spanish Civil War.

The Falling Soldier

The most iconic image of the Spanish Civil War – and indeed of Capa’s career – is the photograph of a Spanish Republican militiaman falling down wounded on the Córdoba front line. “The photograph is an overwhelmingly powerful statement of the human existential dilemma, as the solitary man is struck down by an unseen enemy, as if by Fate itself…the photograph is a haunting symbol of all the Republican soldiers who died in the war, and of Republican Spain itself, flinging itself bravely forward and being struck down.” – Richard Whelan, “Robert Capa in Spain”, in Heart of Spain, published by Aperture.

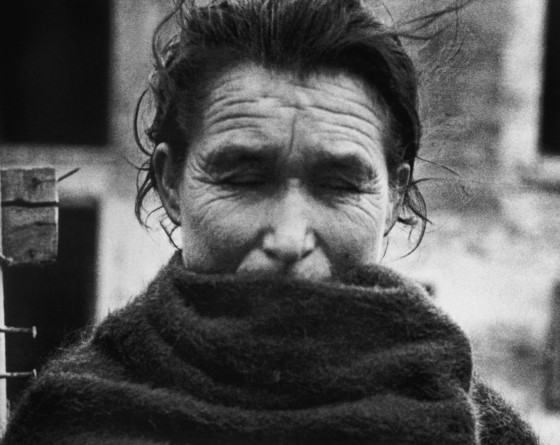

Tragedy for Gerda

In July 1938, after Capa had returned to Paris, Gerda Taro stayed in Madrid. On hearing about a fierce battle that had just launched toward Brunete, west of Madrid, she headed out to document it. The battle was bloodier than any previously, and on the evening of July 25, during the confusion of a retreat, Taro jumped onto the running board of a general’s car to reach safety, but as an out-of-control tank crashed into it, Taro was crushed and died the next day. It is believed that she was the first female photojournalist to die in combat. A radical communist once interrogated by the Nazis over an alleged Bolshevik plot to overthrow Hitler, Taro was given a funeral in Paris by the Communist Network she had been involved with since her arrival in the city.

Capa was inconsolable about Taro’s death when he heard the news. In the preface to the book Death in the Making, dedicated to Taro, he wrote of Gerda “who spent one year at the Spanish front, and who stayed on.” Capa himself would then suffer a similar fate less than two decades later, killed by a landmine during the First Indochina War.