Werner Bischof: The Boy from Roermond

The tragic story behind the photographer's haunting portrait of a child, a victim of war that became emblematic of the dire state of Europe post World War II

As Werner Bischof’s centenary retrospective opens at Bellpark Museum we explore the story behind an image that shook Switzerland, and how and exhibition of the work led to a family reunion.

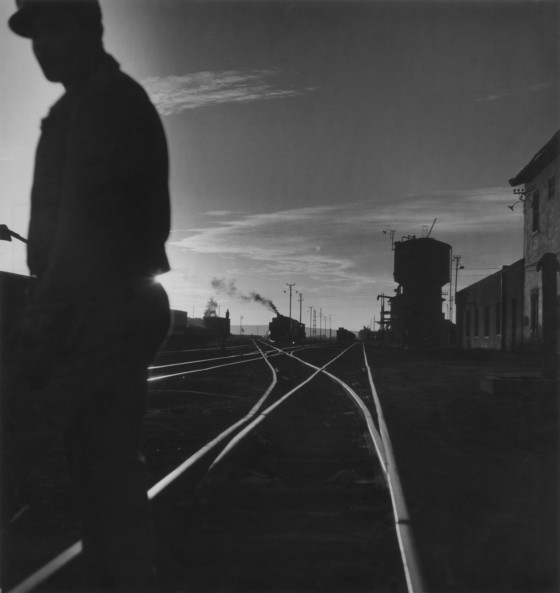

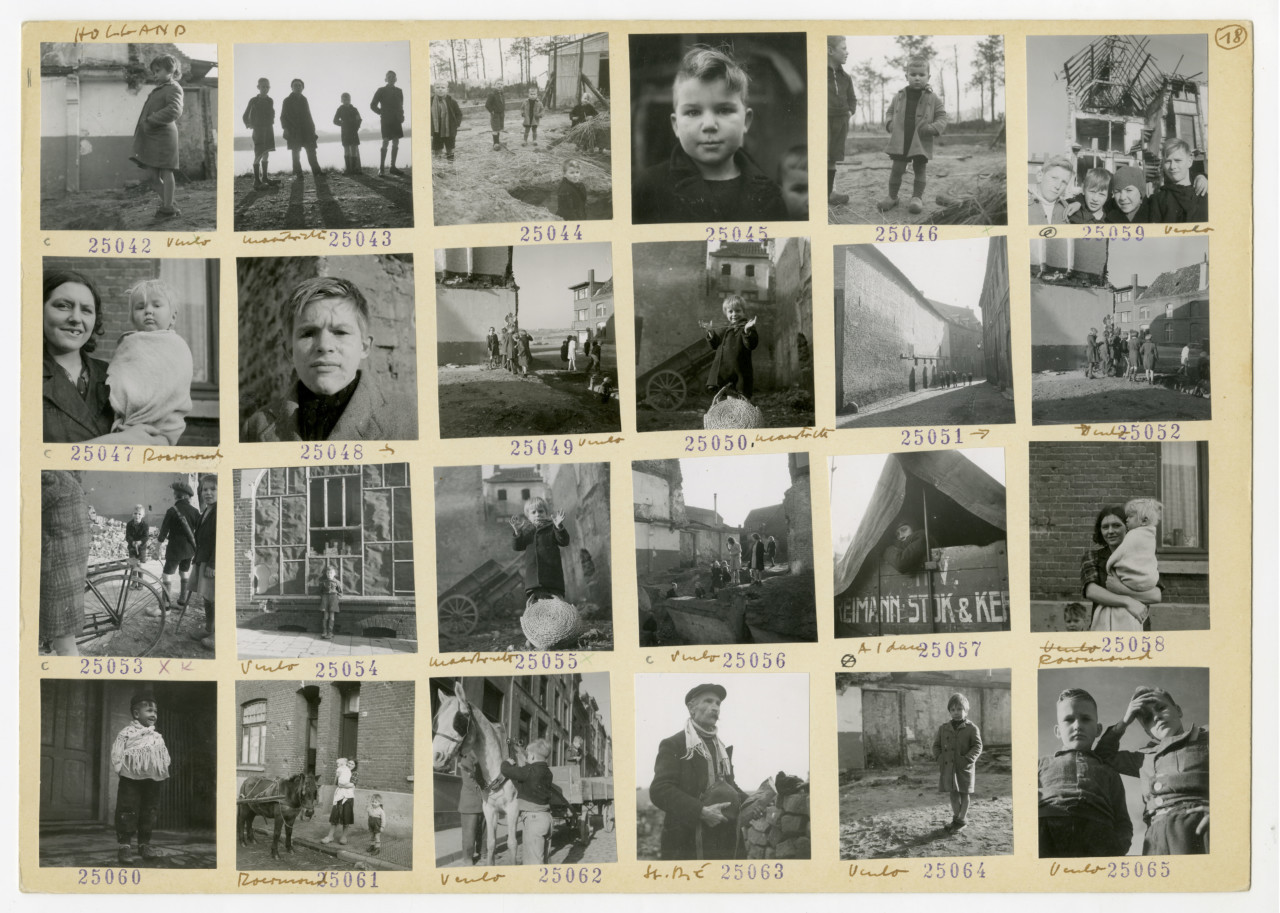

For six months, spanning 1945 and ‘46, Werner Bischof travelled through half a dozen countries in Europe photographing the effects of the war. He was on assignment for Swiss Relief, formed in order to alleviate some of the dire need in Europe, with a particular focus on the continent’s children. He was accompanied by Emil Schulthess, a friend and fellow Swiss photographer, who had a darkroom built into the car they were traveling in.

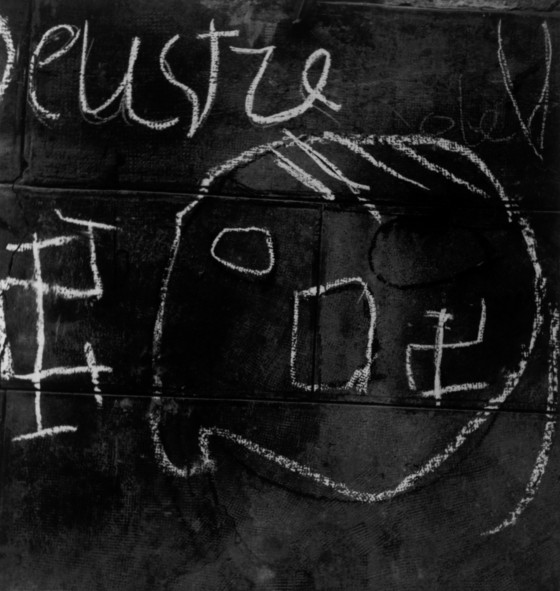

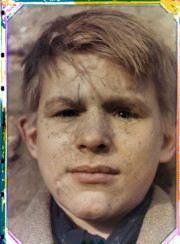

While travelling through Roermond, Holland, in December of 1945, Bischof sighted a boy, visibly injured by the ravages of war, and took his picture. “Roermond is the final stop for today. […] The streets are crowded, and it is not rare to see children with guns and helmets as toys – oh, these cruel toys,” he wrote in his diary. “At the post office, where I am waiting, a boy arrives with a shredded face, blue-violet burn marks from the shrapnel, a glass eye and a red mask, the tender red flesh a cruel contrast.”

Another journal entry, this one by Schulthess, recalled the heartbreaking story of how the boy sustained his injuries: “When the German army had to evacuate Roermond, they laid thousands of booby traps absolutely everywhere: in doorways, in the boiler, in closets, behind doors, behind boxes, in baskets, in sewing projects, etc. Horrible. The boy opened a door that was hitched with a booby trap. He lost his right eye and his face was disfigured by shards. There are hundreds of such cases in Roermond alone, this was not a unique one. His mother was run over by a car two months ago and died and now his father is left to struggle alone with nine children.”

"They could not put the boy out of their mind"

- Arnold Kübler (Editor of Du Magazine)

Bischof made the image using early color photography technology– with a Devin Tricolour Camera. The picture is taken with three black and white glass negatives with filters, then the picture is enlarged and then put together. The markings seen around the edges of the photo are part of this process. Town of Roermond, Netherlands 1945.

On completion of the trip in the winter of 1946, Bischof began to sort through the materials gathered, which included over 2,000 images of devastation and destruction, both of towns and landscapes, and of the lives of those eking out an existence in them. Du magazine’s May 1946 issue was called simply, “Images of Europe”, and featured a color portrait of the boy from Roermond on the cover, along with a call to “Help the Children of Europe”.

The magazine contained a letter from the editor explaining the decision:

“Dear friends, we realize that the boy whose face confronts you on the cover of our May issue can hardly seem appealing. We would like to explain why we have chosen to present you with such a disturbing image: the content of this issue presents only a small sampling from over 2,000 photos shot by Werner Bischof during six months of travel through half a dozen countries in Europe. The Swiss Relief financed his passage along what, in these hard times, could not help but be an arduous journey. In late fall of the previous year, he and Emil Schulthess drove by car through France, Belgium, and Holland. They met this little boy on the street in Roermond; he had a glass eye and a disturbingly scarred face tinged blue by the morning chill of 12 below zero Celsius. Although they had to press onward with their journey, they could not put the boy out of their mind.”

The publication of the magazine and its cover provoked controversy, with the heaviest criticism coming from a medical practitioner who stated in a letter to the editor that the public display of a larger-than-life-size colour photograph of a suffering and injured child demonstrated a serious lapse of taste. The ensuing controversy forced the editor-in-chief Arnold Kübler to publish an apology, together with a statement on the purpose of photography, where he explained his decision to publish the image of the child suffering.

Decades later, Werner Bischof’s son, Marco Bischof, identified the name and life story of the boy. When he opened a show in 2011 of his father’s work, entitled, “The Compassionate Eye: Photographs, 1934–1954” in the Gemeentemuseum in Helmond, a small city close to Roermond, local press supported the museum’s campaign to find people who might be able to identify the boy. Eventually, Gerrit Corbey, recognised his twin brother Jo.

When curator Frank Hoenjet and Marco Bischof met Gerrit Corbey and other family members, they learned of a tragic succession of events. After Jo Corbey was injured by shrapnel from an explosion in March 1945, he and his nine brothers and sisters lost their mother in an accident, in October of the same year. A drunken English soldier had run into her with his truck while she was on the road. At their mother’s funeral, the children were divided among the other family members (even though their father was still alive) and subsequently lost touch with each other. They would not come together again for 70 years, and Jo’s portrait would play a pivotal role in the reunification.

Werner Bischof met the boy shortly after these events, in November 1945. According to a presentation given by Marco Bischof and Karin Priem of the University of Luxembourg, diary entries by Werner Bischof from this time indicate that, “though the photographer was not aware of all the details of Jo Corbey’s backstory, he immediately felt ‘terribly afraid that this young life [would] be destroyed even more.’”

"It is not rare to see children with guns and helmets as toys – oh, these cruel toys"

- Werner Bischof

Just a few years after Bischof took the photograph, Jo Corbey died from poor health related to his injuries at the age of twenty. “The life story of Jo Corbey received much attention and was given radio and television coverage,” said Priem, adding, “the photograph taken by Werner Bischof acted not only as mediated memory but also as a social object and actant within a tragic family history. In the interview, family members showed much relief that the past no longer had to be silenced and that emotions could break free.”

Reflecting on the story of Jo Corbey and his family, Marco Bischof said, “This story of the Corbey family, that had been torn apart and brought back together 70 years later through the picture of Jo Corbey appearing in the Werner Bischof Exhibition, shows how photography can still make changes in real life.”

This Story was brought to life through a collaboration with Marco Bischof and Karin Priem.