The Highs and Lows of Notting Hill Carnival

Gemma Padley explores archival photographs that capture the joviality of the famous carnival but also highlight its troubles

Magnum Photographers

*This article, with newly digitized images from Chris Steele-Perkins was published in 2016. The 2017 Notting Hill Carnival will incorporate tributes to the victims of the Grenfell Tower fire. The disaster, which happened close by in West London, not only directly affected communities who are involved with the yearly carnival, but also brought to the fore issues of class, race and wealth divides that have fuelled the tension around the future of the Notting Hill Carnival.

It began in the name of hope for a more tolerant local community. The Notting Hill Carnival, has, for the past fifty years, been a mainstay of London’s cultural calendar. The now two-day event, which falls over August bank holiday weekend, welcomes visitors and performers from across London, the UK and the world.

Now recognised as one of the largest and most popular carnivals in Europe, the West London carnival has its roots in the 1959 Caribbean Carnival organised by Trinidad-born activist and journalist Claudia Jones. The ‘cabaret-style’ event took place in St Pancras Town Hall and featured, among other things, a beauty contest and steel band dance troupe.

Its genesis was, in part, a reaction to the racially motivated violence that took place a year earlier, in which groups of white locals brutally attacked the West Indian residents who had settled in the area. Days of rioting saw white mobs rampage through Notting Hill leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. The carnival in 1959 can be seen as something of an attempt to heal a deeply troubled community.

Other indoor carnivals in London followed until 1964 when social worker Rhaune Laslett took up the mantle after Jones’s death. Laslett’s vision was for a street party – the London Notting Hill fair and pageant – that championed cultural unity and tolerance, and it was this that set the wheels of Notting Hill Carnival in motion.

A celebration of London’s diversity

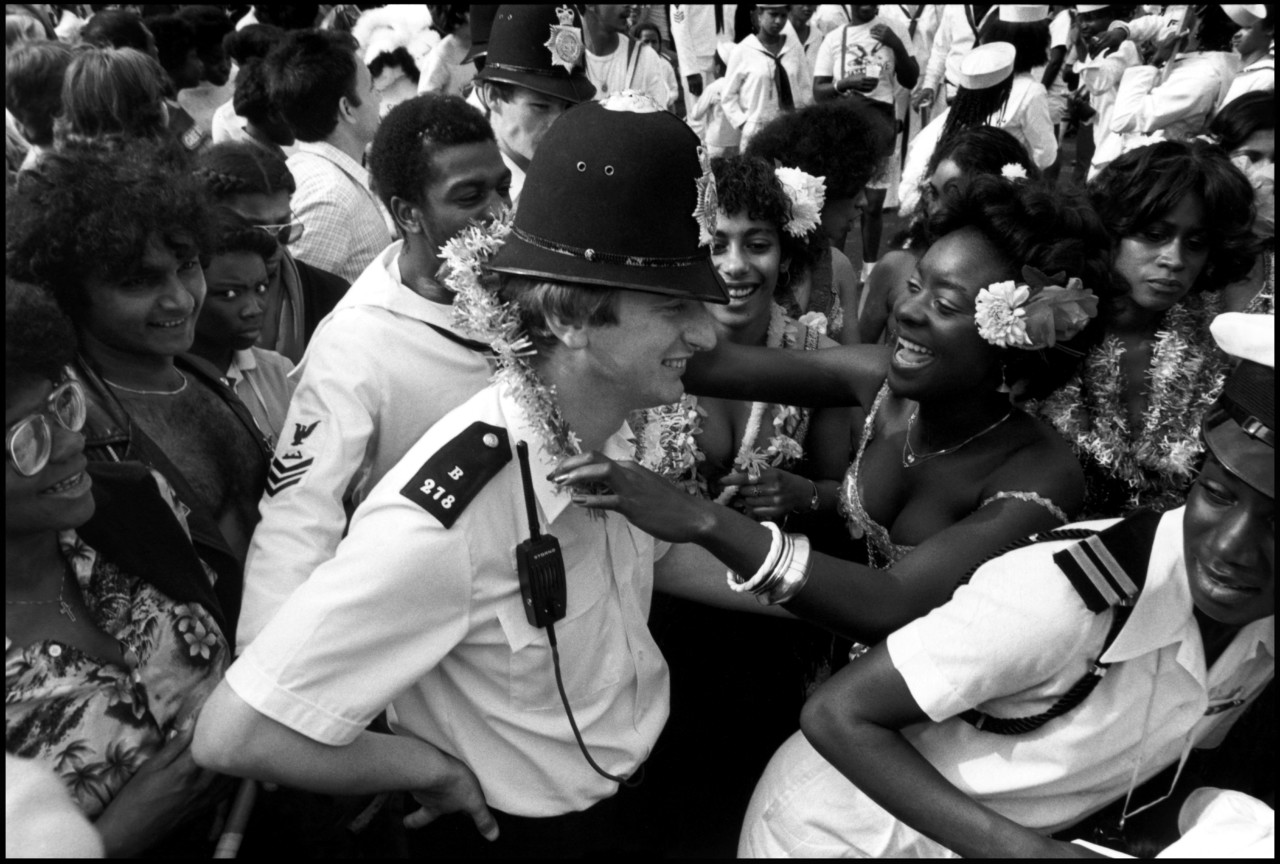

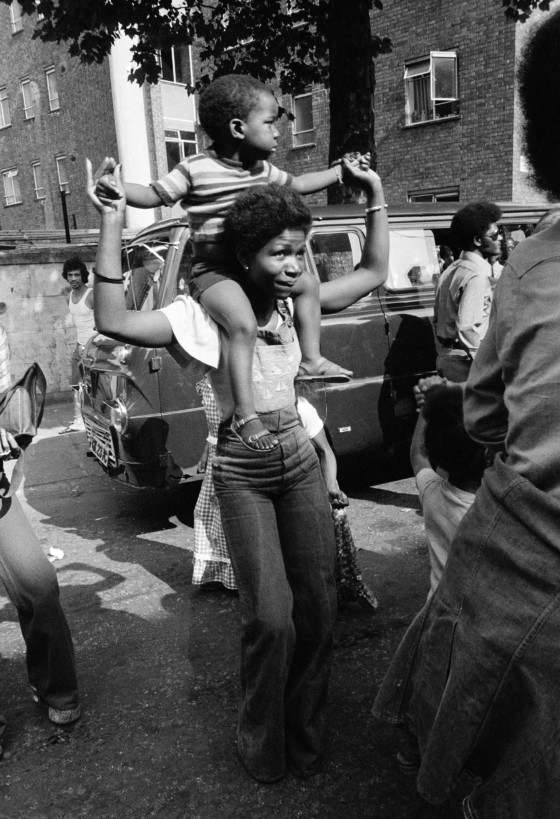

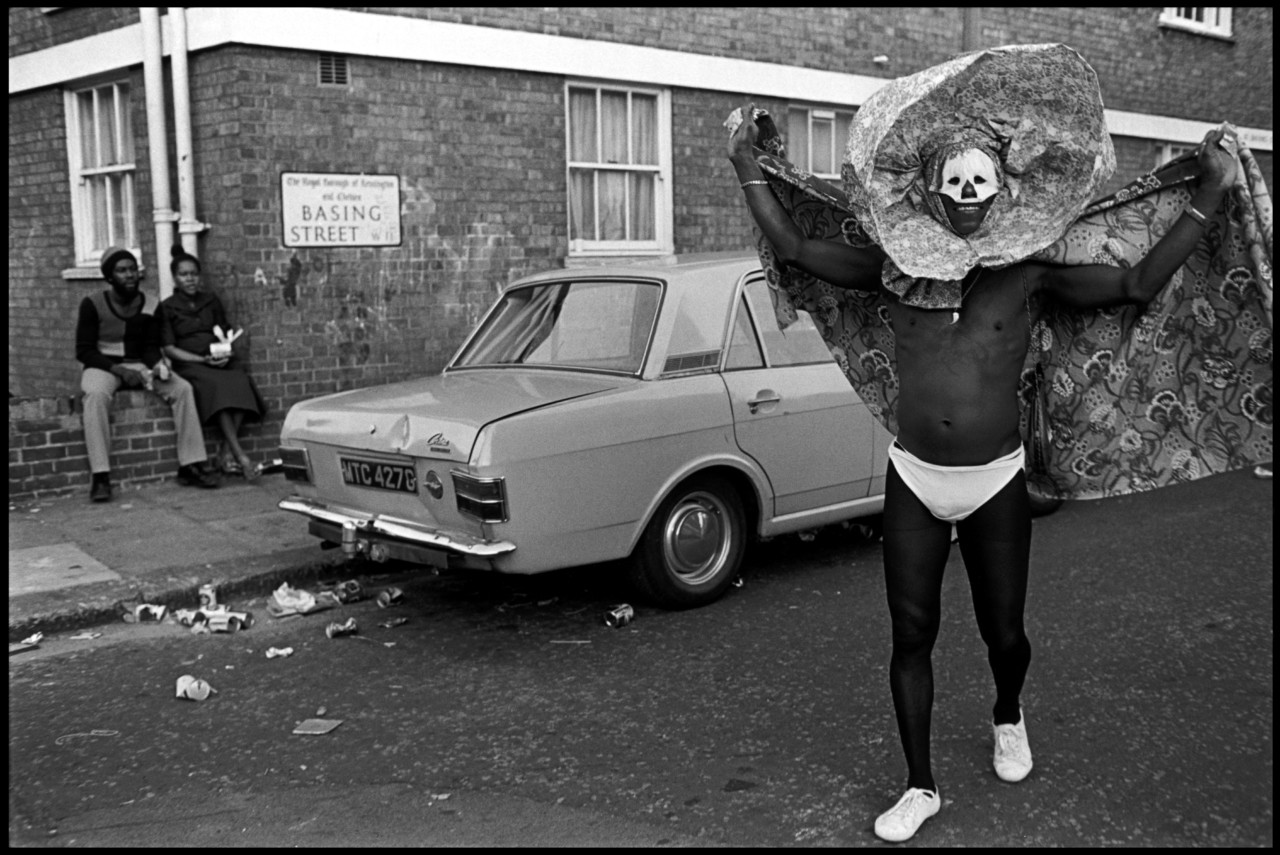

As the images of Magnum photographers Chris Steele-Perkins and Ian Berry attest, the carnival is a coming together of people from all walks of life, a celebration of multiculturalism through music, dance, and elaborate costumes. Steele-Perkins attended several times in the 1970s, and Berry photographed the carnival on at least two occasions, in 1981 and 1997. Both photographers captured black and white people enjoying the festivities together, with Berry capturing a policeman amid revellers, smiling and looking relaxed. Images such as these show the famous carnival at its best, where the focus is on unity, not division, merriment, not destruction.

"This is photography at its most potent, where a skilful hand composes an image that alludes to something outside of what is being immediately depicted"

-

Tensions running high

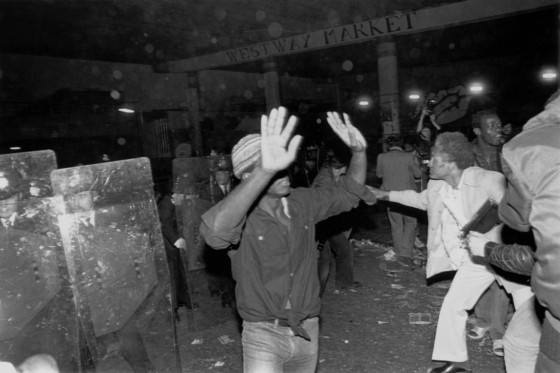

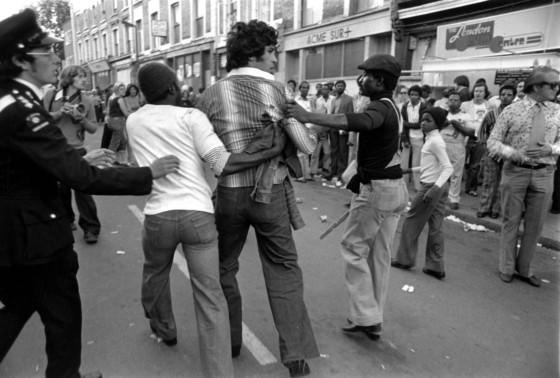

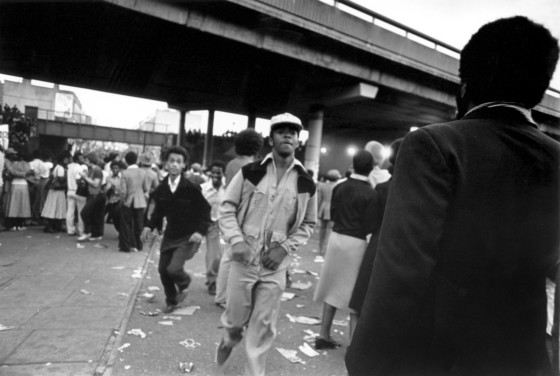

The carnival has experienced its share of difficulties. Steele-Perkins and the late Peter Marlow are two Magnum photographers who captured some of the less pleasant moments on camera, producing images that offer a glimpse of the carnival’s darker side – one of distrust and violence. Both were present in 1978 when scuffles broke out and police used shields in a bid to restore order. One image by Steele-Perkins clearly makes the point about racial tensions: on the right of the image, three stony-faced policemen are pictured with shields, poised to act, while on the left, a black man, his body language defensive, looks on warily, dwarfed by the policemen who dominate the frame. The image exudes unease, and, almost forty years on, we are left wondering what happened next. As if the sense of division in this image wasn’t clear enough, a conveniently placed post in the centre, physically separating the man and policemen, hammers home this message. This is photography at its most potent, where a skilful hand composes an image that alludes to something outside of what is being immediately depicted: in this instance, the distrust between merrymakers and the police that had been present at the carnival for years.

"supporters are determined to protect the carnival’s future"

-

Notting Hill Carnival today

The carnival today has become a symbol of the city it takes place in – dynamic, vibrant and multicultural. Sporadic flare-ups still occur, reflecting the urban harbinger of life that is London, of which the two-day festival is a microcosm. This year, there have been news reports that talk of a heightened sense of alert amongst authorities as they anticipate the current political climate feeding into the weekend’s atmosphere. Other tensions have also intensified between participants and residents in the now-gentrified, fashionable neighbourhood in which the carnival takes place. Residents have been complaining of noise, overcrowding and the inevitable party aftermath, leading to calls for the festivities to be moved elsewhere. A report fifteen years ago recommended that the carnival be relocated to Hyde Park or an area of open land near to Wormwood Scrubs prison to ensure safety standards were met. And in 2015 calls for it to be moved surfaced again as The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea council entered into discussions with the London Notting Hill Carnival Enterprises Trust to address residents’ concerns.

Despite the present tensions that overshadow the carnival’s original ethos – a celebration of togetherness, of diversity – supporters are determined to protect the carnival’s future. In 2015, the campaigning group Green Westway launched a petition to secure UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity status for Notting Hill Carnival to protect “this important London, British, and global celebration…safeguarding the carnival’s future as a festival in the streets of Notting Hill”. The key word here is ‘celebration’, something Berry captures perfectly in his image of a group of carnival-goers laughing and cavorting, taken at the 1997 carnival.