Turkey’s Dying Democracy

Charting Turkey's decline in freedoms as President Erdogan tightens his grip over the country

Magnum Photographers

Just a few years ago, European politicians and Western experts praised Turkey as a model of stability in the Islamic world; a democracy—perhaps flawed—that was nevertheless bridging the East and West, promoting secularism and negotiating EU membership.

But since then, Turkey has rapidly slid into authoritarianism. A reminder of just how quickly things have changed came on November 18, when the EU announced plans to slash funds allocated to Turkey by $124 million and to freeze another $70 million in the 2018 budget. The lead rapporteur for the budget said it was sending a clear message to those that “depart from our democratic standards and breach fundamental rights” that EU money “can’t come without strings attached.”

In recent years, Magnum photographers like Emin Özmen, who joined as a nominee in summer 2017, have been charting Turkey’s departure from these democratic standards. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who initially served as prime minister from 2003 to 2014, once promised religious freedom and economic growth to the Turkish people. But ever since the Gezi Park protests of 2013, he has clamped down on opposition groups and increasingly embraced a stark form of authoritarianism.

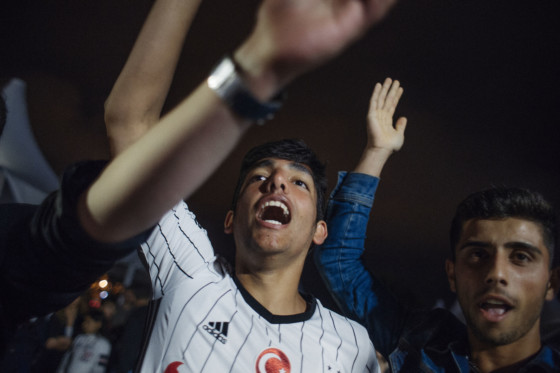

The Gezi protests were the largest wave of protests in Turkey’s recent history. More than 3.5 million people are estimated to have protested against concerns over freedom of expression, the war in Syria, Erdoğan’s authoritarianism and the government’s encroachment on the country’s tradition of secularism—including curbs on alcohol.

Erdoğan dismissed the protestors as “a few looters,” but Özmen says it was clear from the first day in Taksim Square that it was a turning point for Turkish democracy. “There was a revolutionary breath,” he says. Police used tear gas and water cannons to suppress the protests; eleven people died and more than 3,000 were arrested. That “only increased anger and increased protests in the heart of Istanbul.”

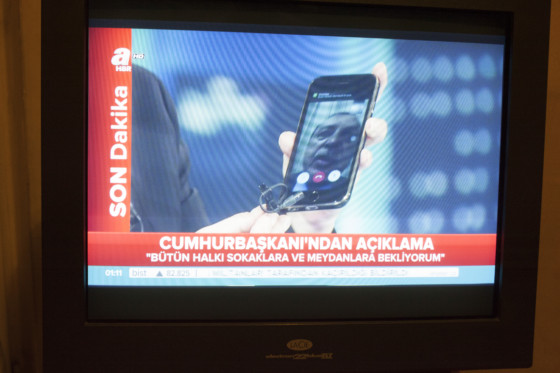

Political instability further wracked the country after the opposition pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) won an unexpected electoral victory in June 2015, surpassing 10 percent of the popular vote. That allowed them for the first time to create a HDP voting bloc in parliament and marked the first defeat for Erdoğan’s party since 2002. Erdoğan and his allies began to rely on violence to consolidate power. Then, in July 2016, the situation in Turkey escalated rapidly after Erdoğan managed to survive an attempted coup on July 15 that killed 265 people.

"I had the feeling that something historic was happening."

- Patrick Zachmann

Patrick Zachmann, on assignment at a jazz festival in Istanbul, accidentally found himself caught up in the chaos that night. During the concert, people began to leave and Zachmann’s assistant, a Turkish photographer, looked at his cell phone and learned that the roads in Istanbul were blocked with tanks. “It was completely surreal. More and more people left; it was intense. Nobody knew what was going on,” Zachmann says. After the festival, Zachmann and his assistant rushed back to the hotel and then to the assistant’s house, which was near Taksim Square. “It was really an atmosphere of war,” he says, describing the sound of shootings coming from Taksim Square and war planes overhead. “There was confusion; people running and screaming.”

Zachmann’s background is not as a news photographer—but he knew that being in Istanbul that night was important. “I had the feeling that something historic was happening.”

He says his strongest photo is of the “soldier looking at me, almost in fear.” It reminds him of a famous photograph of the Chile coup in 1973 by David Burnett. “It was the same fear, but here it was the soldiers who were afraid rather than the civilians and the activists in Chile.”

The failed coup attempt revived Erdoğan’s presidential ambitions and helped him to push his political agenda; he has been able to paint those who do not support him as anti-Turkish or anti-Muslim—and therefore enemies of the state. The legitimate need to bring the perpetrators to justice has spiraled into a sweeping purge. Ankara declared a state of emergency and suspended some elements of the European Convention on Human Rights. About 60,000 people have been arrested and 150,000 civil servants have been fired or suspended by executive decree, largely with no evidence. Protests in the Kurdish cities of south-east Turkey were also brutally quashed.

“Everything was turned upside down,” says Özmen. “Arrests, purges, trials… Fear and suspicion reign.” The lack of independent media, he says, means that the Turks have access to only one point of view—that of the government. “I am a journalist and so far I have been able to do my job freely, taking precautions. But I feel a constant tension because at any moment, false accusations can be made against me.”

According to a 2017 report from U.S.-based human rights watchdog, Freedom House, Turkey’s press is now classified as “not free.” Over the last decade, Turkey’s decline in political rights and civil liberties ratings has been dramatic—after Gambia, it has had the highest drop in the world. More than 150 journalists have been imprisoned—Turkey jails more journalists than any other nation—and hundreds of NGOs and media outlets have been closed down.

The country’s polarization along familiar fault lines has only deepened with the resumption of the Kurdish conflict and the profound trauma of the coup attempt. In April 2017, Turkey voted to approve amendments to the constitution that diminished the role of parliament and gave Erdoğan an executive presidency that he could hold for at least a decade. Erdoğan’s victory was narrow, with the opposition saying the vote was marred by fraud and intimidation in the run-up to the elections.

"It’s very disconcerting, like our life is on hold."

- Emin Özmen

“Politics has become a very sensitive subject in Turkey, to the point of dividing families,” Özmen says. Society is split between “those who support Erdoğan’s politics and sometimes support him in a fanatical way, and the others, who seem to have resigned themselves—exhausted, breathless, lost without a real leader of the opposition.”

But the Turkish people haven’t entirely resigned themselves to their fate. In July 2017, Özmen photographed the Justice March, led by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, chair of the opposition Republicans People’s party (CHP). Thousands marched peacefully for 25 days from Ankara to Istanbul and at least 1.5 million people attended the final rally. “People were asking for true justice, impartial and fair. To protest against Erdoğan’s politics,” Özmen says. “But once the walk was over, nothing. The situation has remained the same as before this movement.”

“Part of the young generation is depressed. Some of them are thinking about leaving Turkey, while others have already left,” Özmen says. “Since the referendum of April 2017, Turkey has been tense and calm at the same time. It’s very disconcerting, like our life is on hold.”

“Many Turks are also tired and depressed with the attitude of foreign media, which evokes Turkey only through Erdoğan’s politics. There is still hope and beautiful things to do. We must also give hope to the Turks, to the ‘others.’”